![]()

Fare Media Catalog - Page Index: |

||||||||||||||||

| Page 1: Fare Tickets and Employee Tickets & Passes | Page 2: Tokens | Page

3:

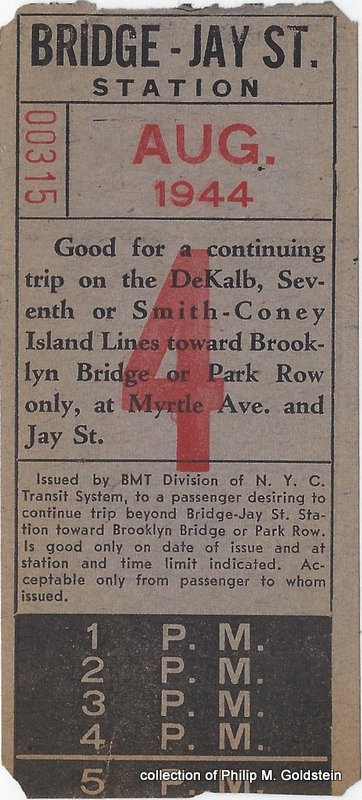

Continuing

Ride Tickets &

Transfers for Rapid Transit |

||||||||||||||

| updated: 10/27/2025 | updated: 1/9/2025 | updated: 3/27/2025 | ||||||||||||||

|

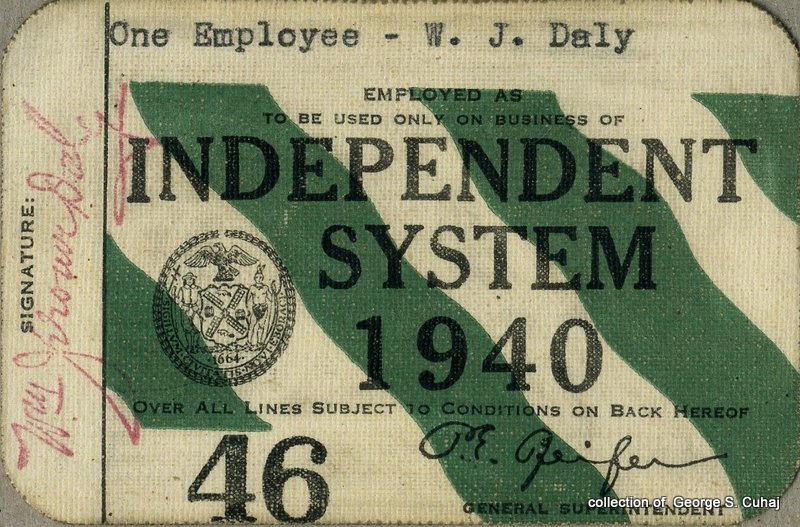

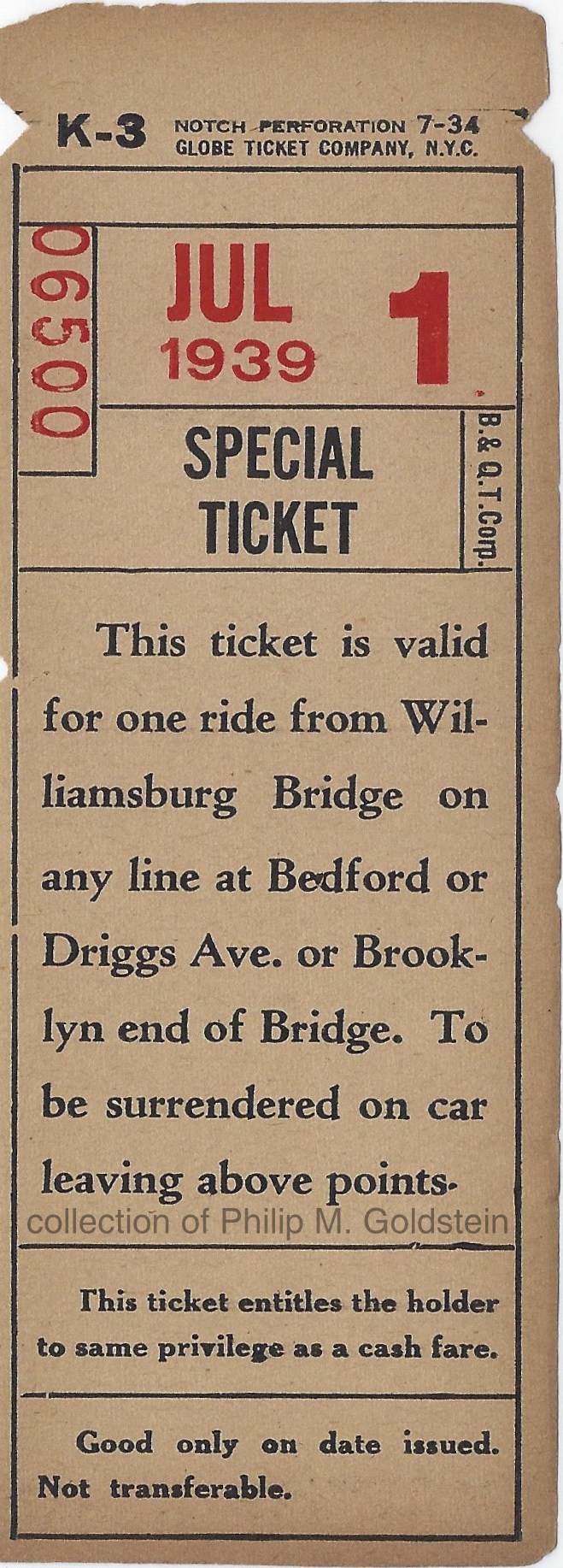

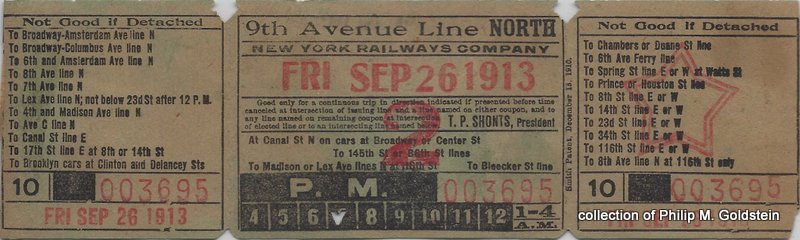

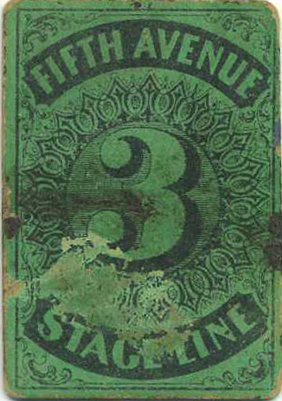

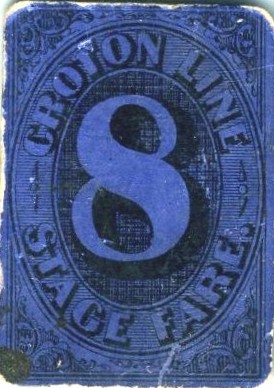

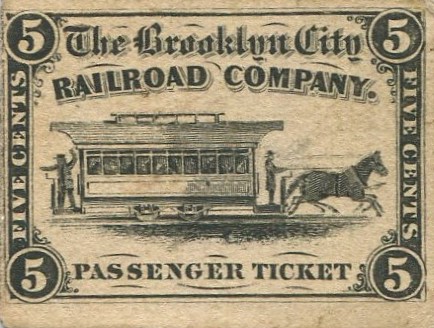

Horsedrawn Stage & Railways, Omnibus Lines, Surface Railways, Elevated Lines & Subways cable & trolley lines for: Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburgh & Queensboro Bridges Employee Tickets & Passes |

|

Horsedrawn

Stage & Omnibus Lines Independent

Trolley & Bus Lines |

|

Internal & Interdivisional: Rapid Transit to Rapid Transit Rapid Transit to Surface Transit Surface Transit to Rapid Transit Combination Tickets: Rapid Transit to Surface Transit Surface Transit to Rapid Transit |

|||||||||||

| . | ||||||||||||||||

| Page

4: Continuing Ride Tickets

& Transfers for Streetcar / Trolley: all boroughs |

Page

5A: Continuing Ride Tickets

& Transfers for

Bus Routes: Brooklyn |

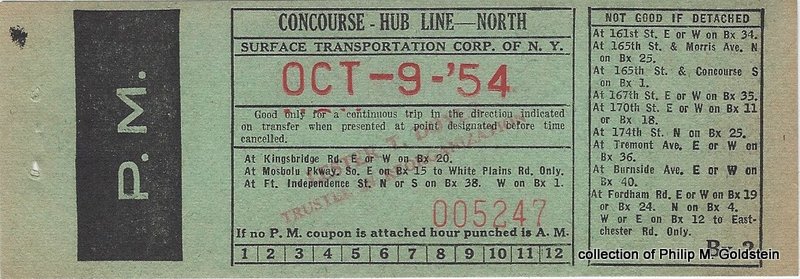

Page 5B: Continuing Ride

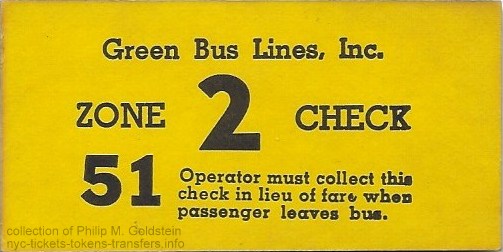

Tickets & Transfers for Bus Routes: Bronx, Manhattan, Queens, Richmond / Staten Island & Express |

||||||||||||||

| updated: 10/27/2025 | updated: 4/13/2025 | updated: 4/13/2025 | ||||||||||||||

|

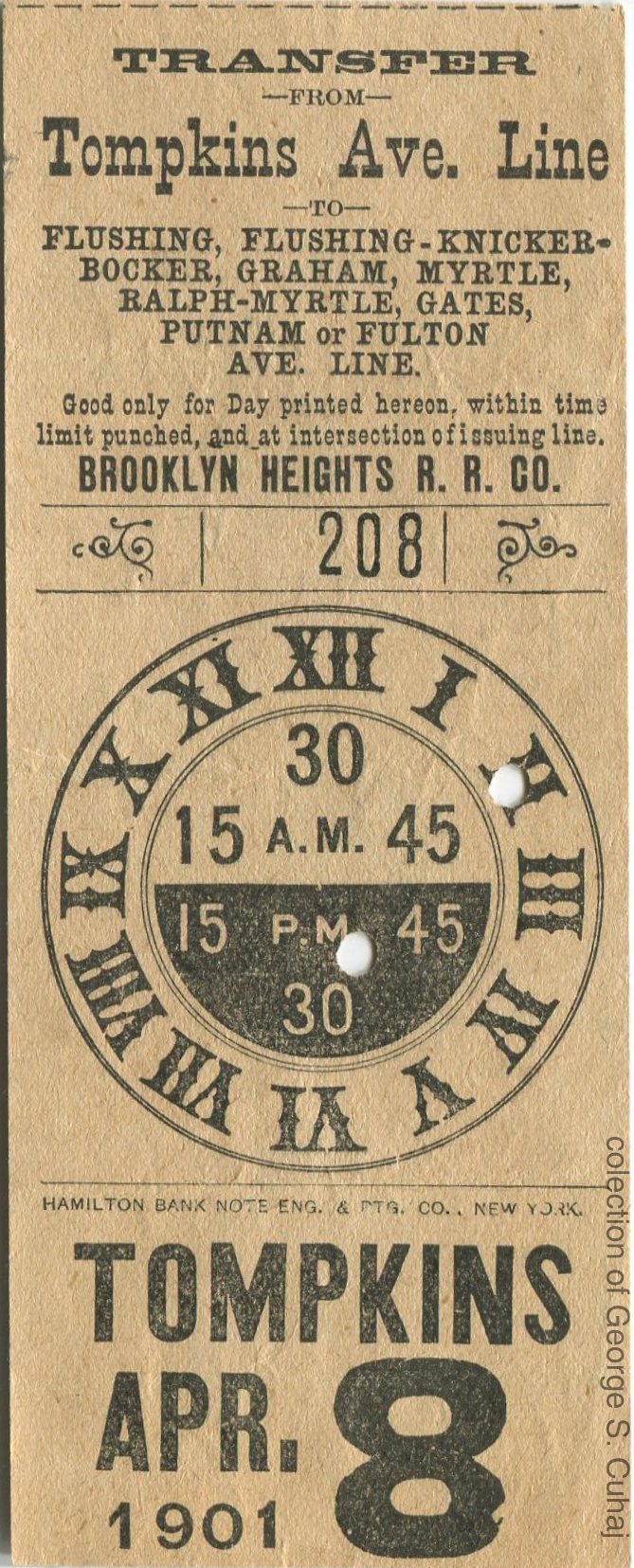

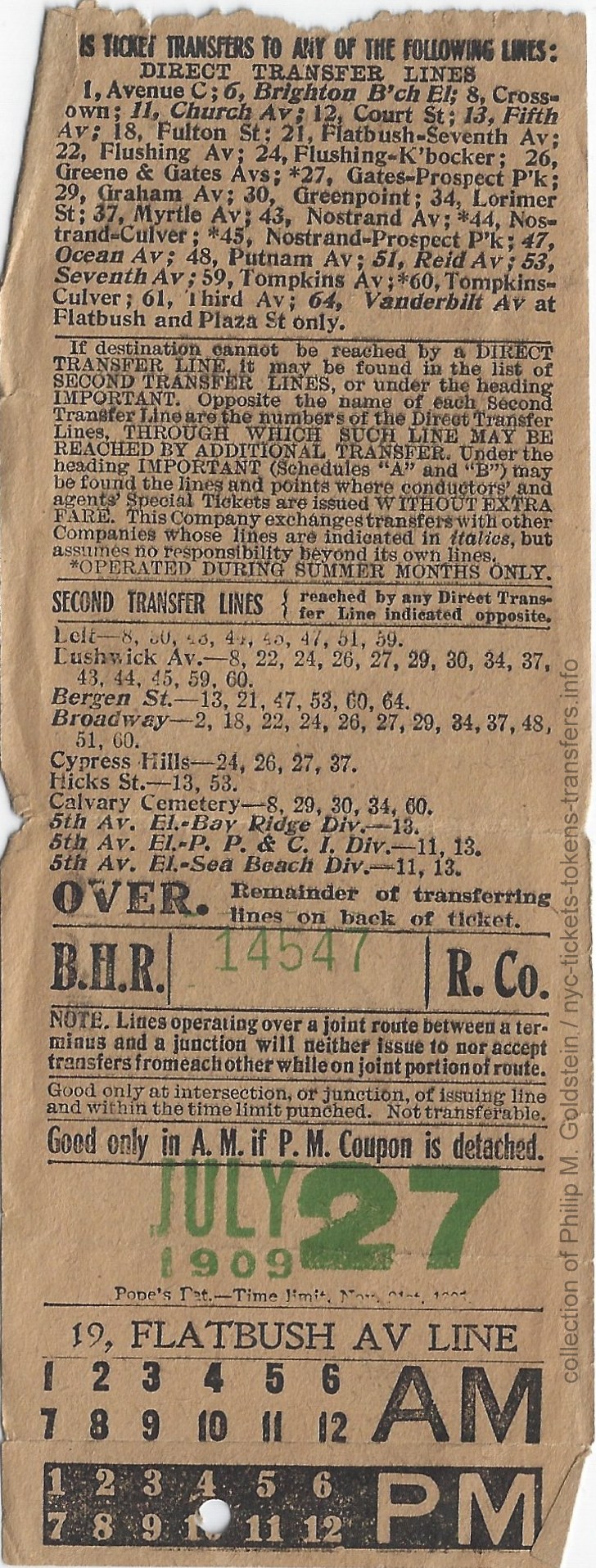

Brooklyn, Bronx,

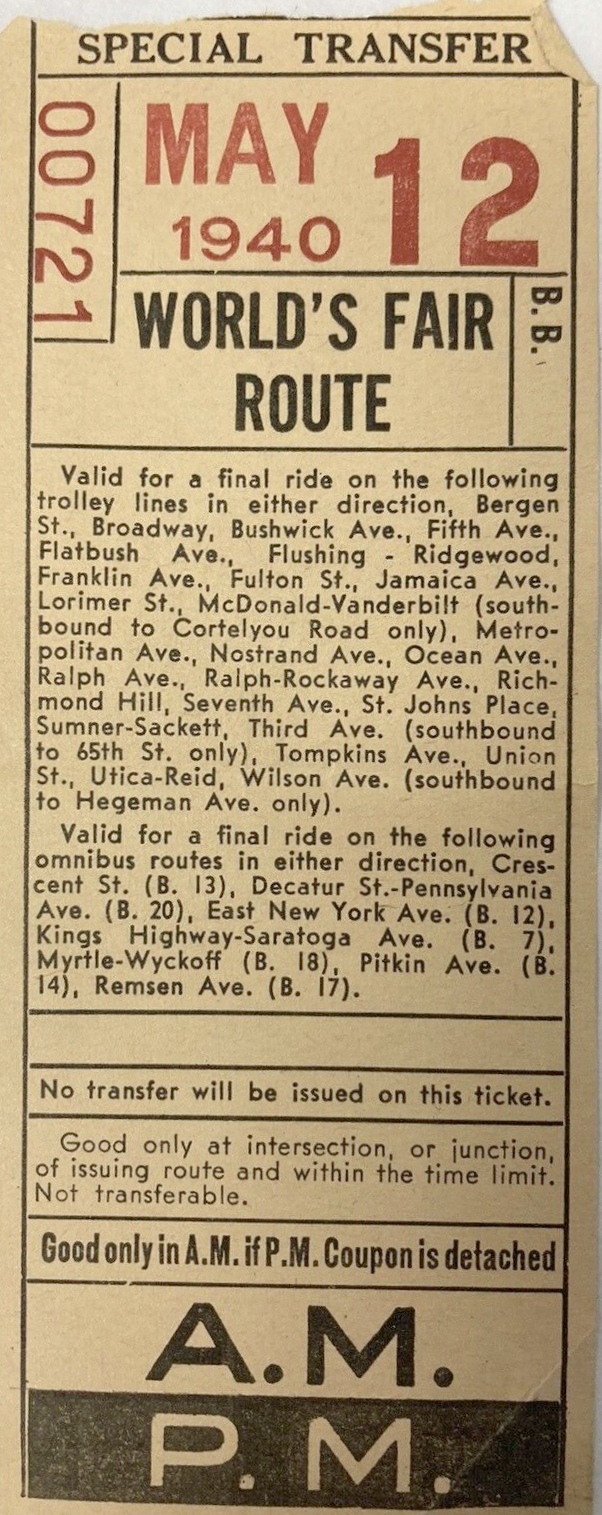

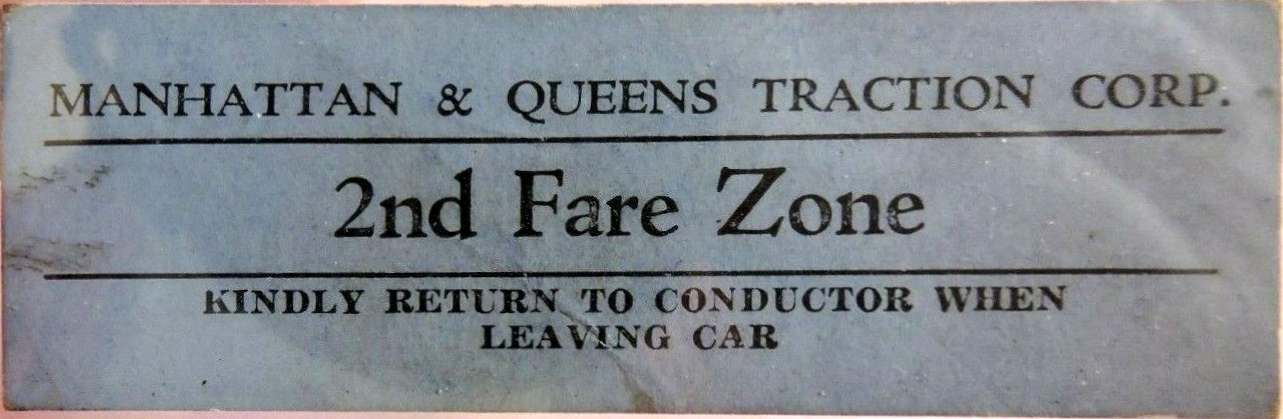

Manhattan, Queens, and Richmond / Staten Island Stedman, Hamilton "Clock", Pope, Smith, Globe Ticket Patents Williamsburgh Bridge Local Continuing Ride Tickets and Transfers Zone Tickets |

Municipal and Private

Bus Lines Interdivisional Continuing Ride Transfers: Surface Transit to Rapid Transit |

. | Municipal and Private

Bus Lines Interdivisional Continuing Ride Transfers Surface Transit to Rapid Transit Zone Tickets |

||||||||||||

| . | ||||||||||||||||

| Page 6: Bus Routes: Add-A-Ride Tickets | Page 7: Subway / Elevated: Half Fare Tickets | Page 8: Subway / Elevated & Bus: Half Fare Tickets | ||||||||||||||

| updated: 4/5/2025 | updated: 6/1/2024 | updated: 4/9/2025 | ||||||||||||||

| Municipal

City of New

York Routes Private Bus Lines |

|

. |

||||||||||||||

| . | ||||||||||||||||

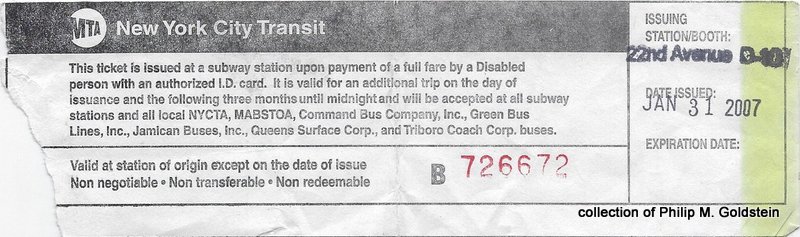

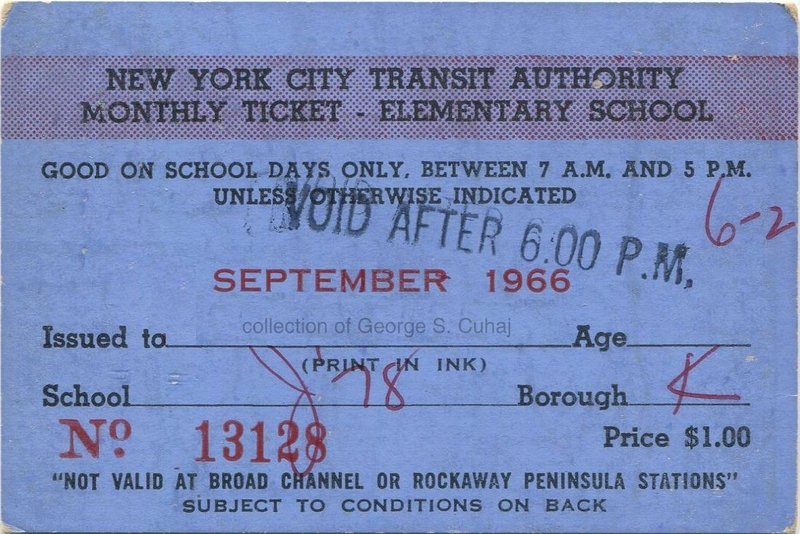

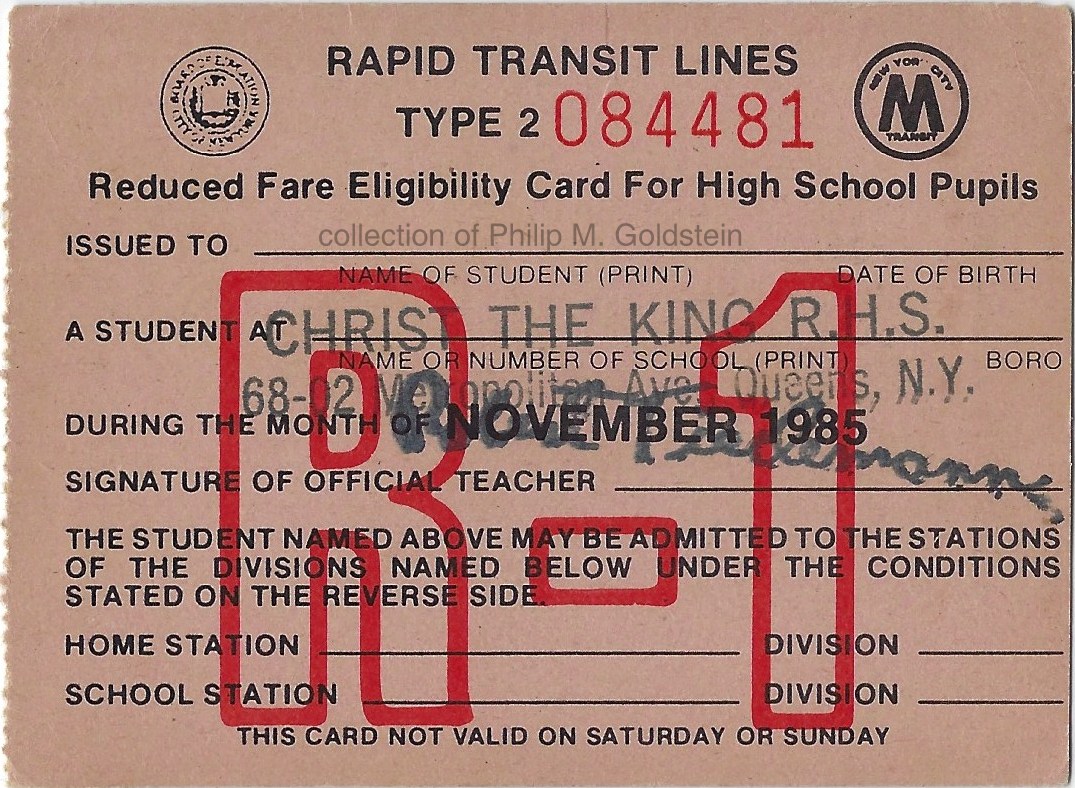

| Page 9: School Tickets & Passes | Page 10: Special Issue Tickets & Passes | Page 11: Staten Island Rapid Transit | ||||||||||||||

| updated: 10/27/2025 | updated: 7/2/2025 | updated: 3/18/2025 | ||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| . | ||||||||||||||||

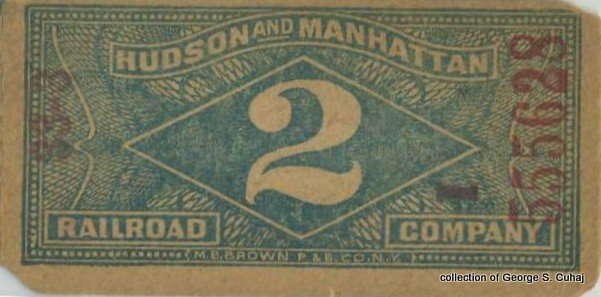

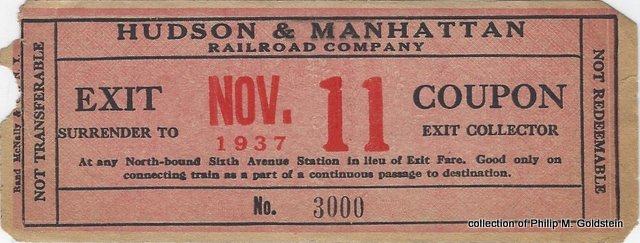

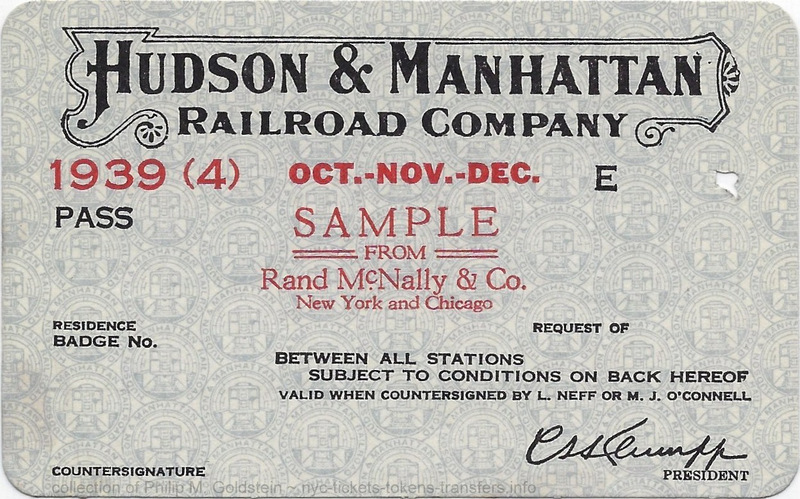

| Page 12: Hudson and Manhattan RR & PATH | ||||||||||||||||

| updated: 4/11/2025 | ||||||||||||||||

|

Tokens, Tickets & Passes | |||||||||||||||

|

|

||||

Pricing and the NYC Transit Ephemera Market: updated: 1/30/2024 |

Special Thanks updated: 1/30/2024 |

Collectors of NYC Area Transportation Exonumia & Ephemera: Facebook Group updated: 7/25/2021 |

||

| Website Dedication updated: 7/25/2021 |

About Your Authors updated: 7/25/2021 |

Bibliography

& References updated: 9/26/2022 |

||

![]()

Hello and Welcome!

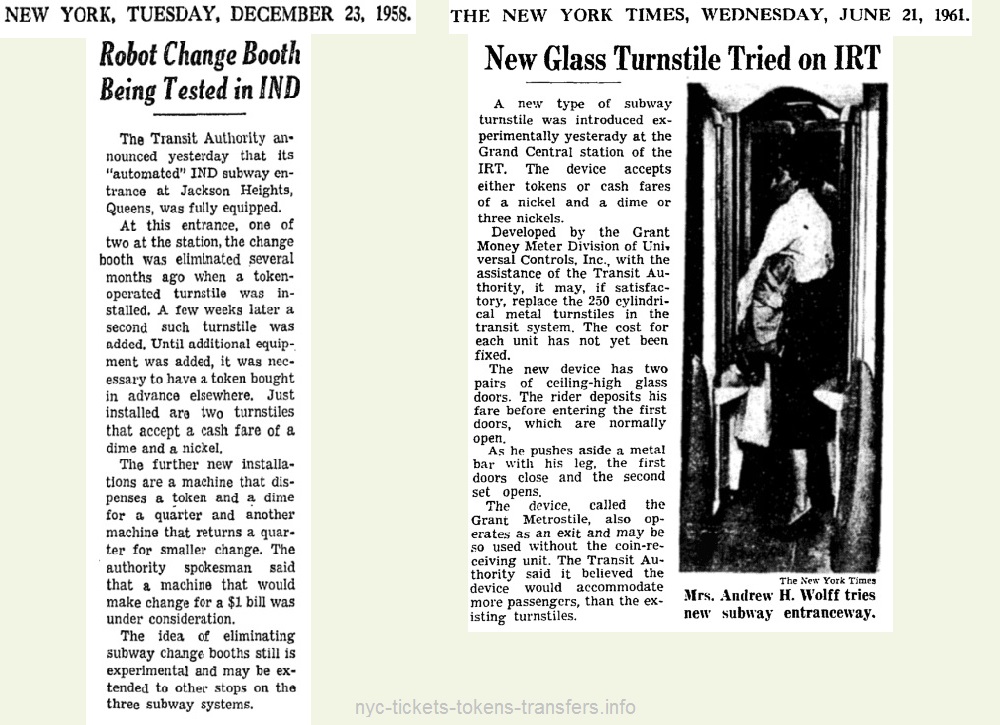

You have found the most detailed and informative compilation of information regarding the fiscal issues and fare control (tickets, tokens, transfers, passes, zone checks, ticket choppers, turnstiles and fare boxes) of transit companies located in New York City. At the current time, we refrain from from digital / electronic methods of payment such as MetroCard and OMNY payment systems.

The history of public transportation in the City of New York has been very well documented in many books, blogs, government reports and newspaper articles, therefore it shall not be our intent to rehash the general history of the construction or operation of the subway. Also, there are many fine authoritative publications and websites that pertain to very specific topics such as: the railroad rolling stock (trolleys, elevated and subway cars) used throughout the decades; station design; sign development; tile color coding, artwork and frescoes; development of the transit maps; etcetera.

In stark contrast; very little had been published about the many fiscal issues – tickets and transfers – that were sold or issued to passengers. So, in recognition of "what was already out there" and what wasn't; this website shall focus on the fare aspects of these transportation companies.

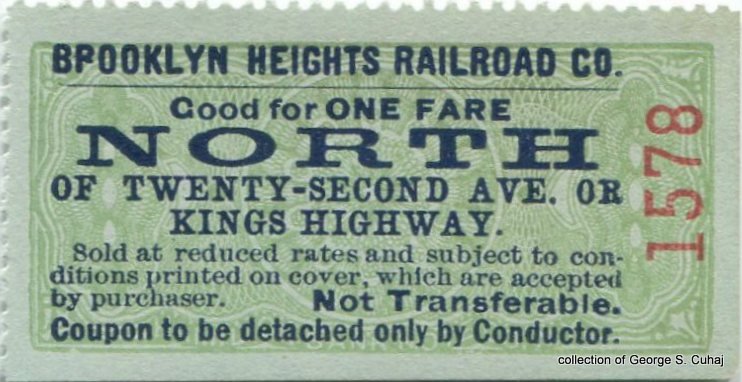

For the early era of operations (1890's to 1953), it is all too commonly thought that passengers simply dropped a nickel into a turnstile and entered the system. But that is not exactly the case. In the very first days, long before turnstiles were invented; and before the subway was built and opened in 1904; there were tickets that needed to be purchased first and they cost ten cents not a nickel.

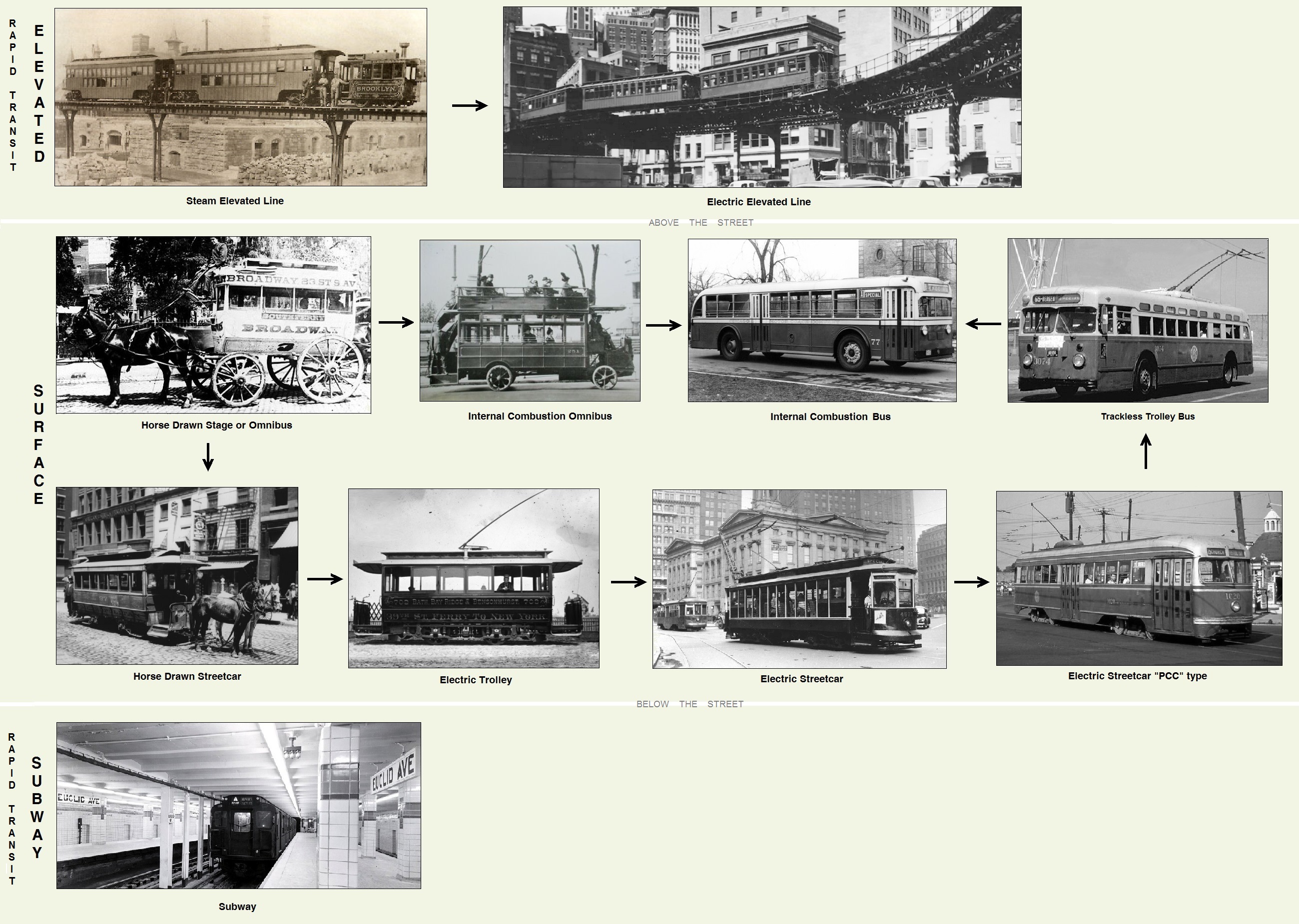

As we will see; there were many more facets to the fare payment process to access the New York City subway and surface systems, past and present; and unfortunately they have remained mostly overlooked until now. So, in this website, we will endeavor to not only refer to the subways and elevateds, but surface transportation methods as well; from the earliest horse-drawn stages and omnibuses, as well as electric trolleys, streetcars to internal combustion powered buses.

Also, many casual New York City Transit history buffs are aware of the original 5 cent "nickel" fare and are under the belief it was universal throughout the city and on all modes of the system. What has been published almost always pertains to the subways and elevated fare, but streetcar and bus fares are hardly mentioned and transfer privileges, if at all; and less so of the private bus franchises.

For the later era of operations (1953 to present), while many people remember the tokens, quite a bit of misinformation abounds regarding some issues; such as which token was the first, when designs were issued (not always in conjunction with a fare raise), etc. In addition to which, there were several special fares for extra services offered both on subway service as well as on surface routes throughout the years.

Furthermore, there are misconceptions and misinformation regarding other fare related items as well. Quite a few of the items on these pages are well recognized (tokens, later bus transfers, school passes) but unfortunately, either urban myth, or revisionist history via blogs and "click bait" web-traffic generator channels have unfortunately twisted some of the facts. On the lesser known items shown, a lot of people simply were not aware of their existence; whether those items were used in the 1800's and had been forgotten over time; or later day issues so limited in their use, i.e.: to a particular neighborhood or short duration of usage.

Equally as unfortunate and in this day and age of social media, this misinformation gets copied, pasted and shared with no regard to its actual veracity. Fallacies and falsehoods are accepted as fact, which is the bane of established historians everywhere. Accuracy and precision make for good historians - not egregious exaggeration and embellishment.

We are not here to pass judgment or criticize those who have made their errors in an innocent way, but our goal is to make sure the misinformation is amended and the correct information made readily available to the general public - at least to those willing to check and accept the veracity of said posted information.

Sadly, even the Transit Museum social media website has been observed lately to post inaccurate information. So much so to the point I have felt the need to create a new chapter to address the matter and to point out corrections in one location. It is hoped that this research and this website will set the record straight and correct those misconceptions and inaccuracies.

Some of these examples of erroneous or overlooked information are:

Furthermore, this website is offered as a collaborative effort between George Cuhaj and Philip Goldstein. We know it is not complete but consider it a starting point for documenting fiscal issues of the land transportation services offered in NYC. It is a companion website to Goldstein’s other "New York Centric" transportation related websites.

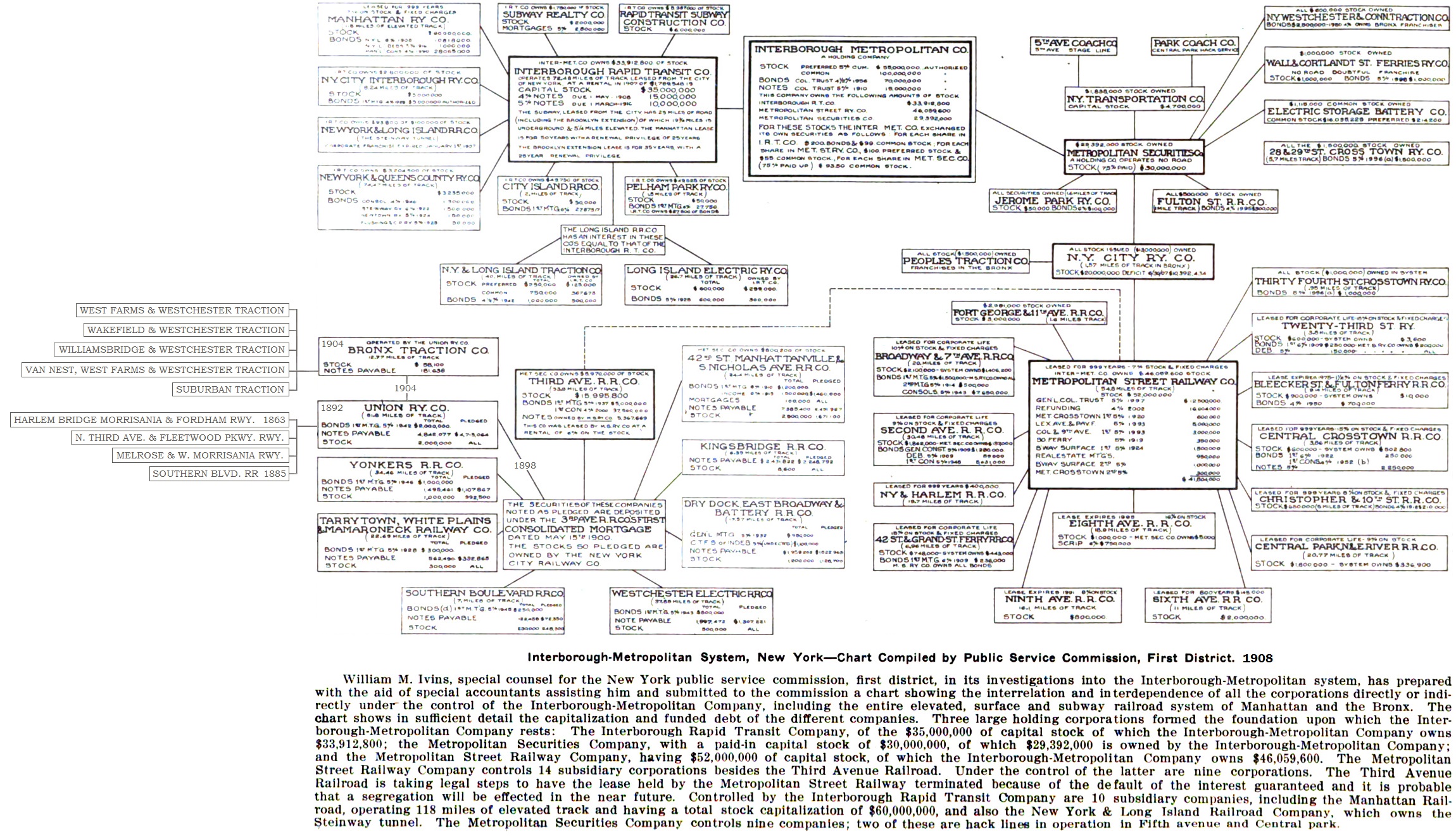

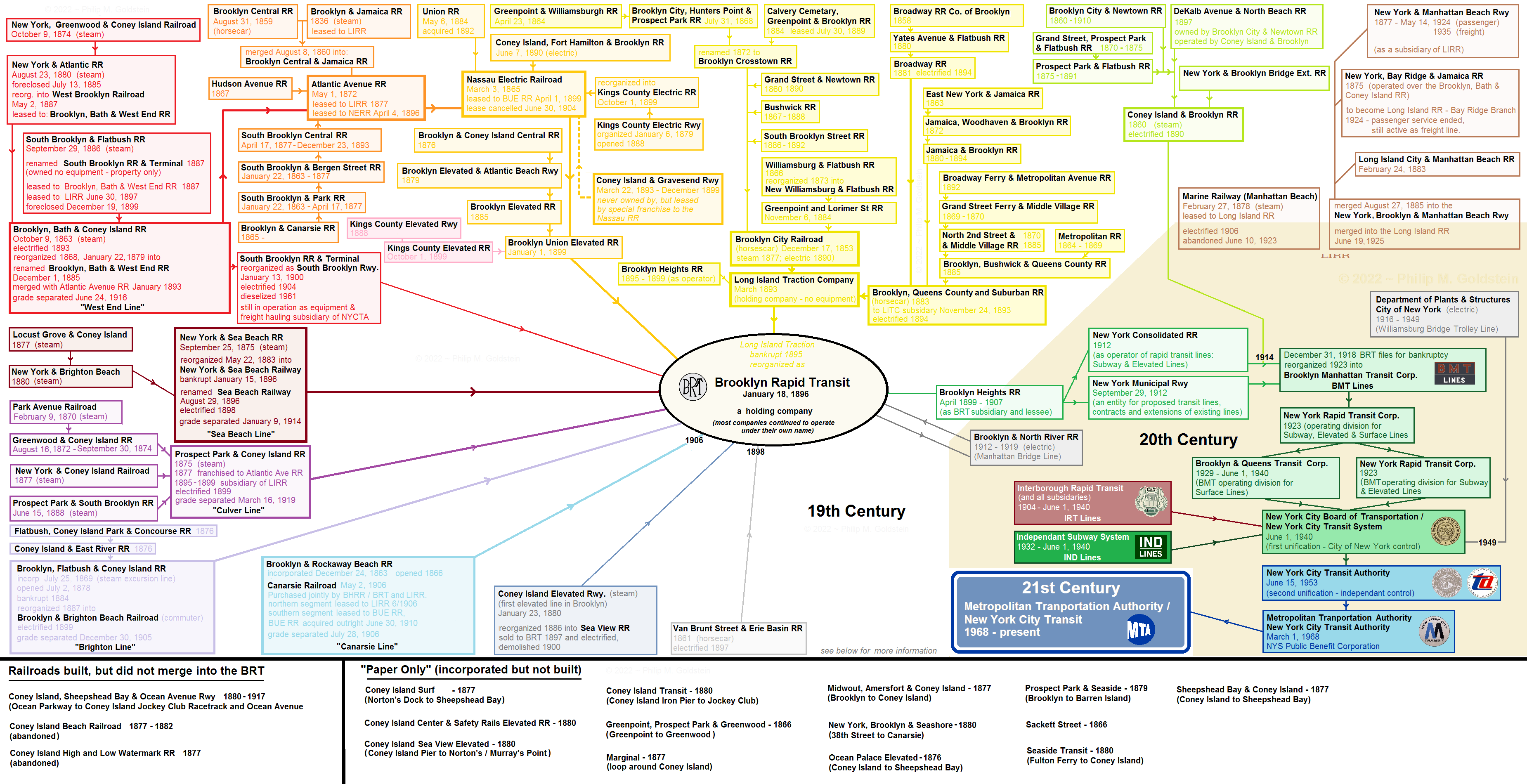

It is emphasized and not expected that this catalog will never be truly "finished" or "complete". There will always be "one more thing" we have not seen and needs to be added; so please bookmark this website and feel free to check back often. Page revision dates are listed either under the chapter link in the index above. It is our intention, to have this catalog become a usable reference and price guide for the active collector (more about this in another chapter below).In developing this website catalog, there four different eras of use regarding transit operations in the City of New York:

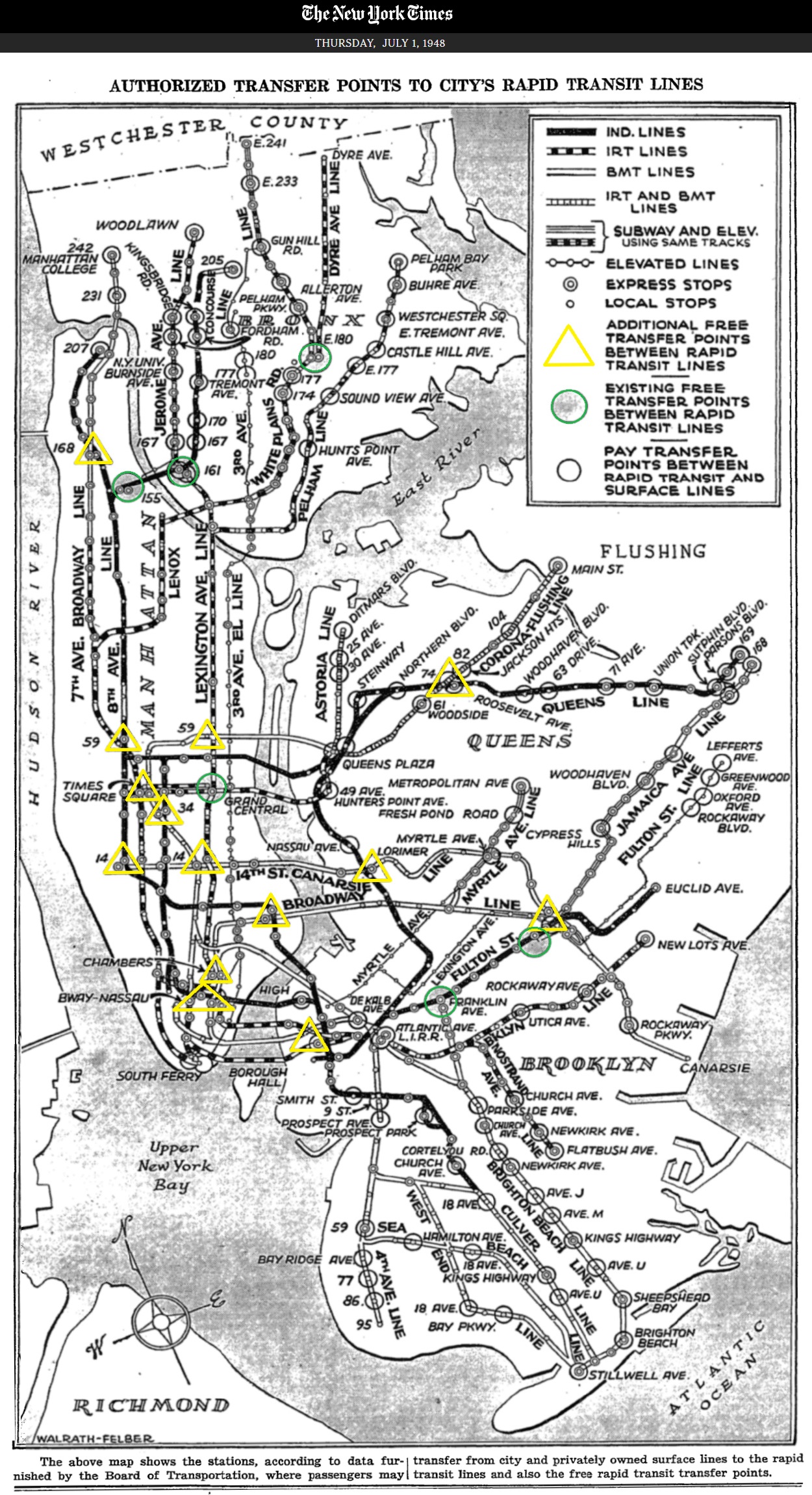

| pre-First Unification | many private companies, surface and rapid transit | 1820's through 1940 |

| First Unification | Board of Transportation - The New York City Transit System | 1940 through July 1953 |

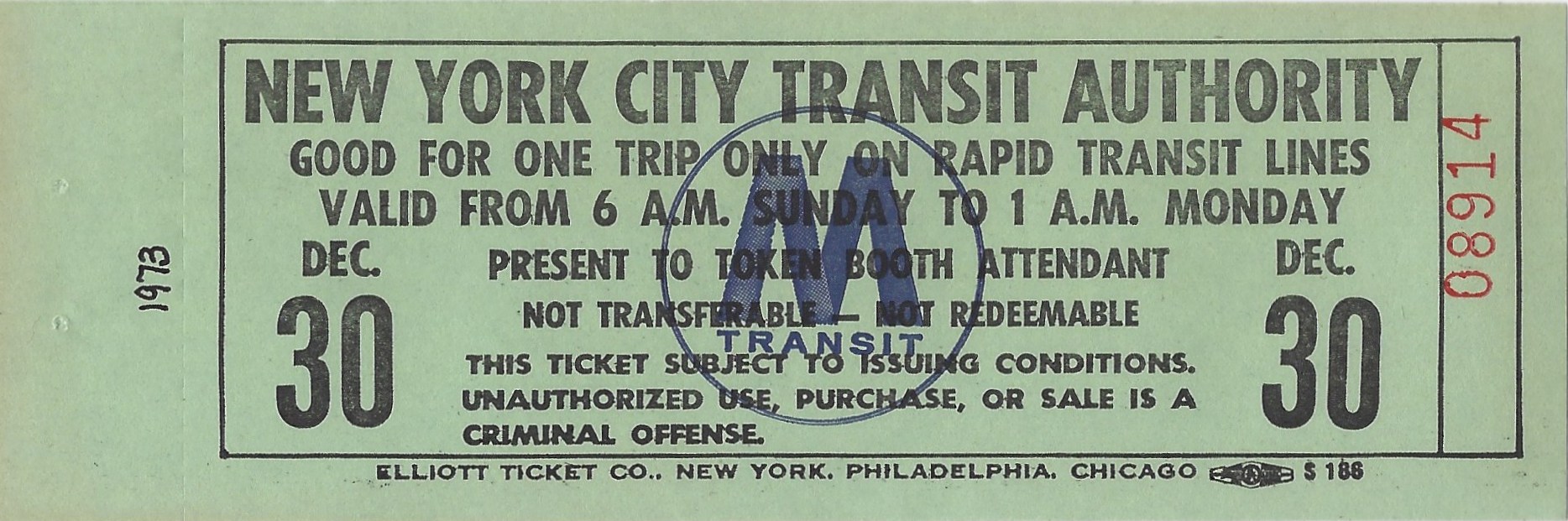

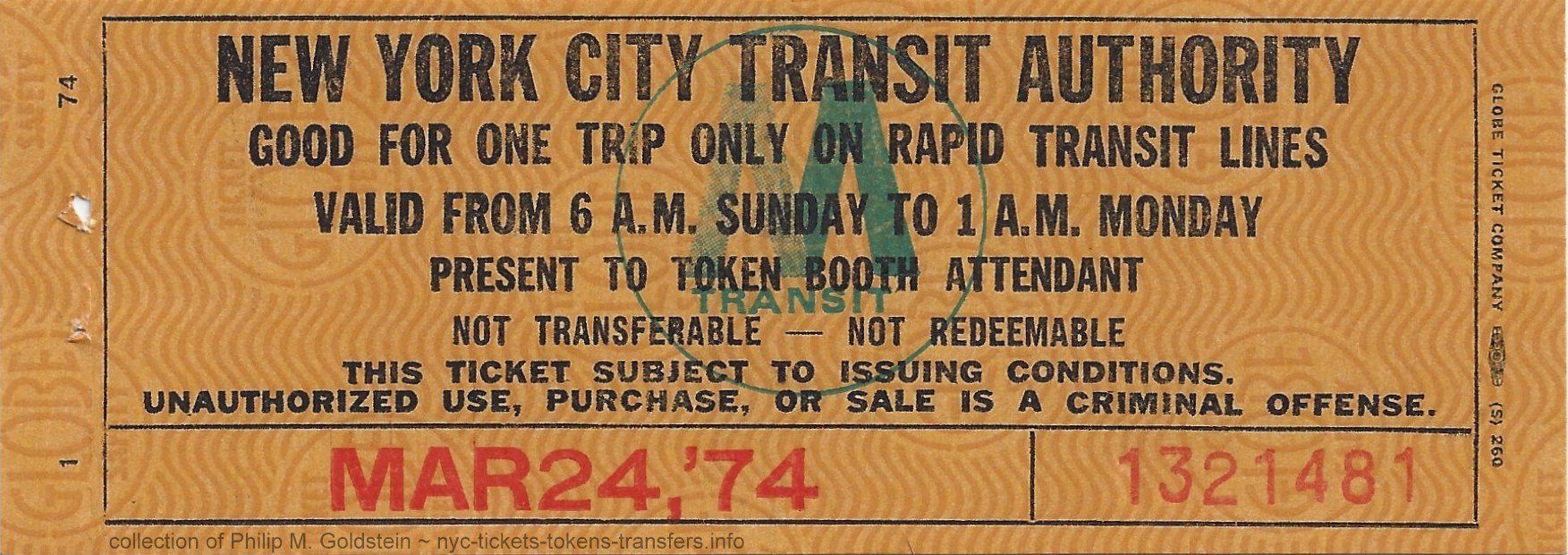

| Second Unification | New York City Transit Authority | July 1953 to February 2006 |

| Third Unification | Private Bus Lines absorbed by MTA - NYCT | February 2006 to present |

Please note: The coverage of this website currently stops at the point in time in which the MetroCard system replaced most of these printed fiscal issues.

| YES! Contributions are welcome! |

If you don't see it on one of the pages of this compilation, we want to know about it!

If you wish to offer an item (or items) for inclusion, you are invited to email us using the contact information at the end of this introduction. Whether you have one piece or many, a ticket, token, transfer or pass or any other fiscal item that you do not see already on any of the pages in this website, you are cordially invited to share them here.

Your submission(s) will be watermarked with your name and your name listed in the special thanks chapter below.

Please feel free to contact me regarding errors, broken links, missing images, corrections, or for any other reason at:

|

brghtnbchexp@aol.com |

![]()

![]()

| operator | start | route | end | fare |

| Sudlow & Siney | NE end of Avenue C | to Houston Street, to Bowery, to Chatham Street, to Broadway and Whitehall Street, to | South Ferry | 4¢ |

| Charles Curtiss & Co | Grand Street Ferry | through Grand Street, to Broadway to Canal Street, to Greenwich Street, to Cortlandt Street, to | Jersey City Ferry | 6¢ |

| Knickerbocker Stage | West 23rd Street | down Eighth Avenue to Bleecker Street, to Broadway, to Whitehall Street, | South Ferry | 3¢ cents on Avenue 5¢ any other |

| C. Lent | East 27th Street | through Avenue A, to Essex Street, to Division Street, to Chatham Street, to Broadway, to Fulton Street, to Washington Street, to | Cortlandt St Ferry | 5¢ |

| J. T. Mills | East 42nd St and Third Ave | to Bowery, to Pearl Street, to Peck Slip, to | Fulton Ferry | 3¢ |

| Mackrell & Simpson | Tenth Avenue and Avenue C | to Avenue D, to Lewis and Grand Streets, to East Broadway, to Chatham Street, to Broadway, to Whitehall Street, to | South Ferry | 4¢ |

| New York Consolidated Stage | West 36 St and Seventh Avenue | down Seventh Avenue and Greenwich Avenue, to Amity Street, to Broadway, to Fulton Street, to | Fulton Ferry | 6¢ |

| " " " " " " " " | West 42 Street and Broadway | Broadway to Whitehall Street, to | South Ferry | 6¢ |

| " " " " " " " " | East 32nd Street and Fourth Avenue |

down fourth Ave, to Broadway & Whitehall Street, to | South Ferry | 6¢ |

| " " " " " " " " | foot of Tenth Avenue | through Tenth Avenue, to Avenue A, to Eighth Avenue, to Broadway, to Whitehall Street, to | South Ferry | 6¢ |

| " " " " " " " " | Broadway and West 39th Street | down Broadway, to Wall Street, to | Wall Street Ferry | 6¢ |

| " " " " " " " " | Hudson River RR Depot | through West 31 Street or neighboring streets, to and through Ninth Avenue, to West 14th Street, to Broadway, to Whitehall Street, to | South Ferry | 6¢ |

| Joseph Churchill | West 32 Street and Broadway | up Bloomingdale Road, to Manhattanville and Tenth Avenue, to | High Bridge | 25¢ |

| S. M. & S. W. Andrews & McDonald | West 42 Street and Fifth Avenue |

through Fifth Avenue and Broadway, to Fulton Street, to | Fulton Ferry | 6¢ |

| D. L. Youngs | NE corner of Avenue C and Tenth Ave |

through Tenth Avenue, to Avenue D, Columbia Street, Bowery, Chatham Street, Park Row, Broadway & Whitehall Street, to | South Ferry | 4¢ |

| Siney, McLelland & Pullis | West 34 Street and Ninth Avenue |

down Ninth Avenue to West 23rd Street, to Broadway and Whitehall Street, to | South Ferry | 6¢ |

| Marshalls & Perry | West 46th Street and Sixth Avenue |

down Sixth Avenue, to Ninth Avenue, to Broadway & Whitehall Street, to | South Ferry | 3¢ (from 42 to Eighth Av) 3¢ (from 42 to Sixth Av) |

| " " " " " " " " | West 46th Street and Sixth Avenue |

through Sixth Avenue to Eighth Avenue, to Broadway & Whitehall Street, to | South Ferry | 6¢ |

| F. Conselyea | Tenth Avenue and West 32nd Street |

down Tenth Avenue, to West 14th Street, to Ninth Avenue, to Hudson Street, to Spring Street, to Broadway, to Broome Street, to Bowery, to Catherine Street, to South Street, to |

Fulton Ferry | 6¢ |

| Johnson & Company | Williamsburgh Ferry and Grand Street |

through Grand Street, to Cannon Street, to Second Avenue, to Avenue C, to East 14th Street, to Third Ave, to East 26th St, to Broadway, to East 32nd St, to |

Hudson River RR Depot | 6¢ |

| O'Keefe & Duryea | Houston Street Ferry | through Houston Street, to Second Avenue, to Bleecker Street, to Broadway, to | Cortlandt Street Ferry | 6¢ |

| Murphy & Smith | Fourth Avenue and East 40th Street |

up East 40th Street, to Madison Ave, to East 23rd St, to Broadway, to John Street, to Nassau Street, to Wall Street, to | Ferry | 6¢ |

Broadway & Fifth Avenue Line

Broadway, Twenty-Third Street & Ninth Avenue

Broadway & Fourth Avenue Line

Broadway & Eighth Street Line

Second Street & Broadway Line

Madison Avenue Line

![]()

|

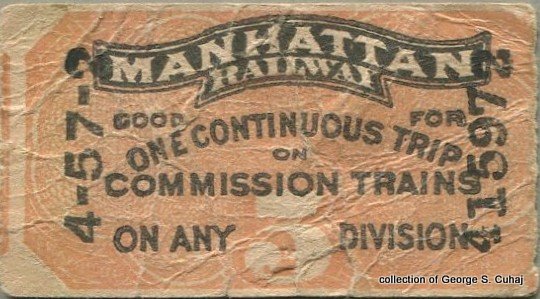

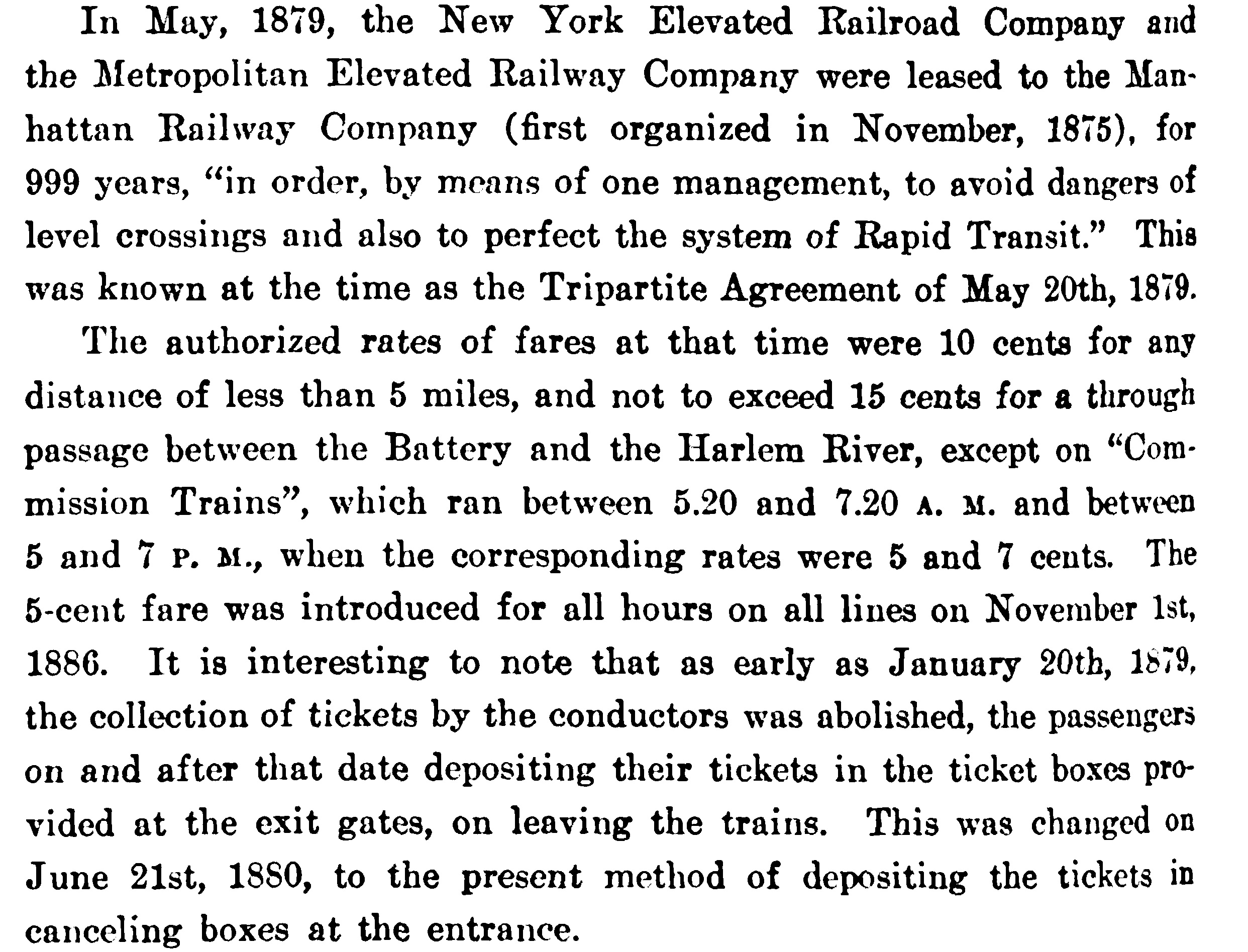

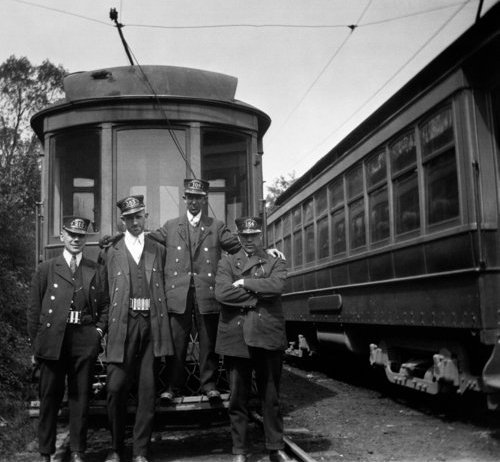

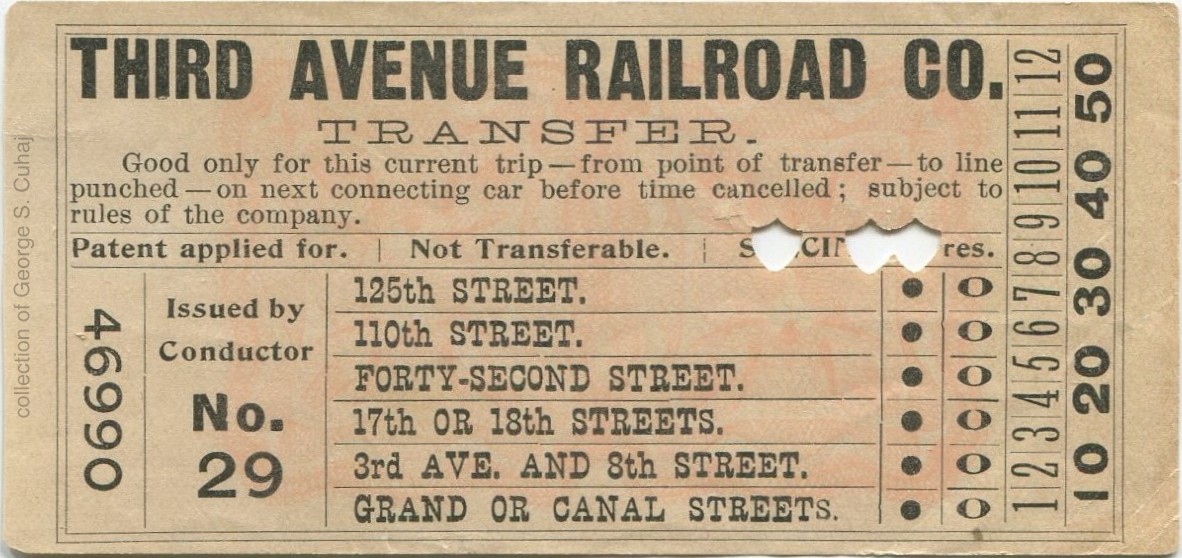

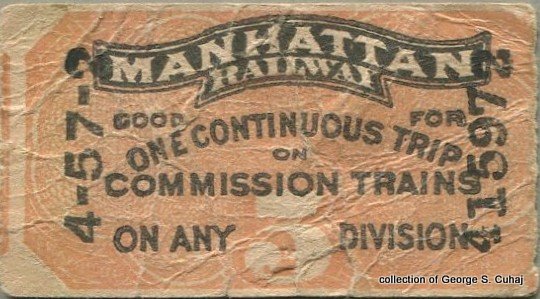

We see as a result of this article, the method of ticket

collection was changed from conductors taking up tickets aboard the

train, which was abolished on January 20, 1879. The reason for this was, at times of large crowds - especially during rush hours; the conductor may not have gotten to taking your ticket before you disembarked at your station; allowing you to ride for free and using your ticket on another date. So, the collection of tickets now required passengers to deposit their tickets into ticket boxes upon exiting the train at the exit gates. With this method, it also caused congestion when trains discharged the passengers in one short time span. And so, on June 21, 1880; the method of ticket collection would change yet again. Passengers now had to deposit their tickets into chopper boxes prior to boarding the trains; and it is this method of ticket collection that would gain widespread use for other rapid transit companies in the Cities of New York, the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens as well. This method worked the best, considering people arriving to purchase their tickets and hand them to the gateman were for the most part spread out over time. Granted, you can still get a crush of people, but the groups were smaller than on discharge of a train arriving in a station. Only on November 1, 1886; would the elevated fare would be reduced to 5 cents "around the clock" and to match other lines, and it is on this date in 1886 - not 1904 with the opening of the IRT subway - that rapid transit operations in New York City first saw the full time "nickel fare". These later era tickets are categorized on the following page: |

.

.

. .

.

Proceedings of the

American

Society of Civil Engineers, August 1917

|

![]()

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

While most consider the NYCTA "dime sized" Y token of

1953 to be the "first" tokens for transit, they were

not. The "Y" tokens may have been the first tokens issued for use by the NYCTA, but:

It is a matter of semantics. The New York and Harlem Railroad was the first streetcar company in New York City to have utilized tokens, and they issued one token design with several counter-stamps in 1831. No documentation has been uncovered yet to determine the meaning of the counter-stamp varieties (distance traveled? fare discount? route?) In the earliest of use, tokens could be either a metal of soft to medium hardness that can easily be struck, such as: pewter, copper, brass or German silver; or a hardened rubber compound also known as "Vulcanite" which could be manufactured in different colors. |

|

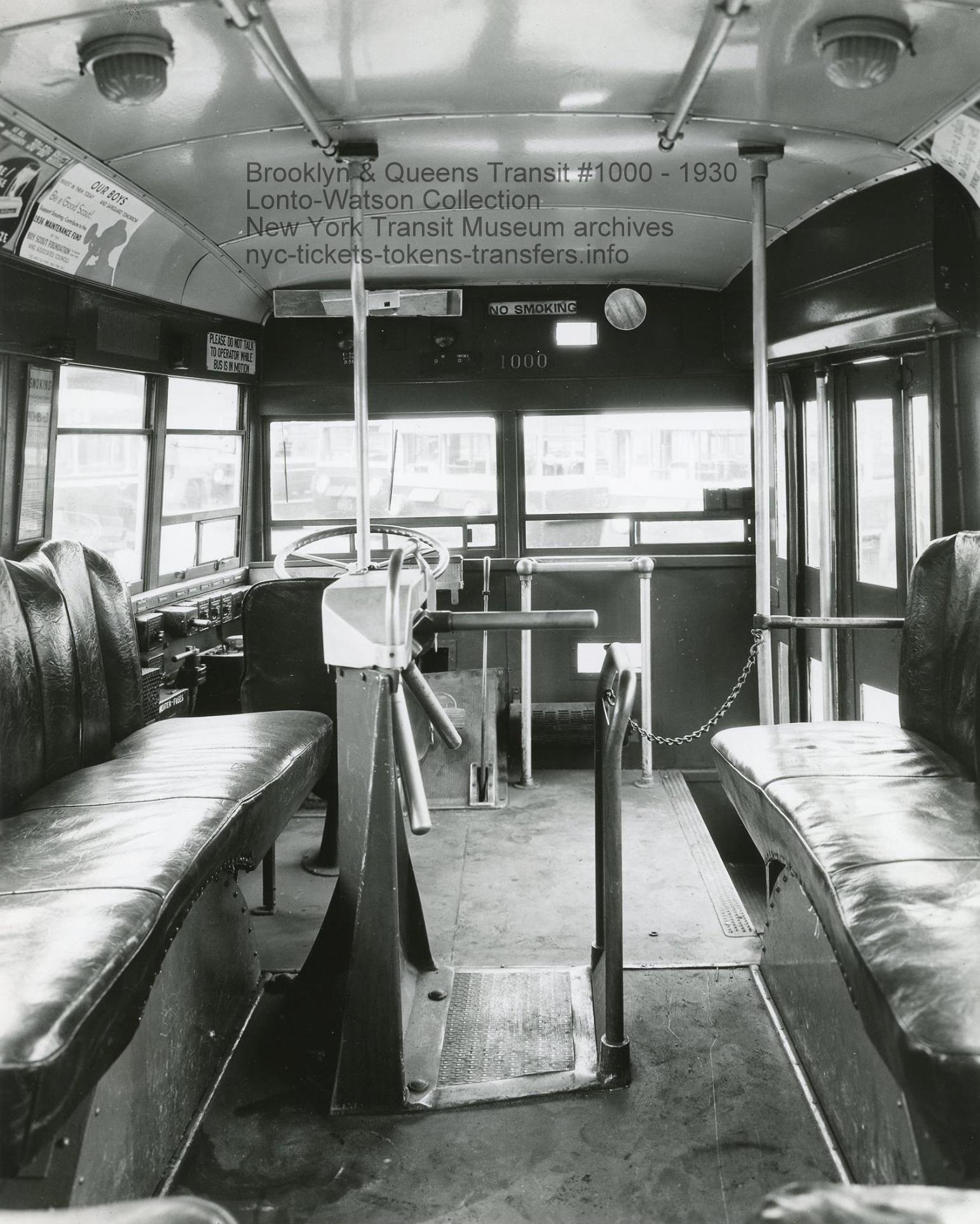

unknown model turnstile on Brooklyn & Queens Transit bus #1000

Note distance of turnstile behind operator. 1930 - Lonto/Watson collection New York Transit Museum archives |

The procedure is thus:

1) Passenger boards first bus / streetcar, requests transfer and pays fare (plus cost of transfer if not free). 2) Driver makes change to the passenger and issues paper transfer. 3) Passenger turns and takes two steps to rear, deposits coin(s) in onboard turnstile, and goes through. 4) Passenger moves to back of bus / streetcar. At the desired connecting stop:

5) Passenger alights from first bus / streetcar, proceeds to second bus / streetcar loading location. 6) Passenger boards second bus / streetcar, hands driver paper transfer. 7) Driver issues metallic "In Exchange For Transfer" to passenger; 8) Passenger deposits token into turnstile, goes through and moves to rear. |

Perey Model 48 "HD" on Brooklyn & Queens Transit PCC Car #1001

Note distance of turnstile behind operator. Note the change maker on dashboard. This image further exemplifies the use of said transfer tokens: why would any passenger need a token (or a coin) to proceed through a turnstile if they already paid the operator? For accounting. |

Page 2 - Early Tokens - 1827 - 1940

Page 2 - First Unification: Board of Transportation / NYCTS - City Wide Issues - 1940 - 1953

![]()

|

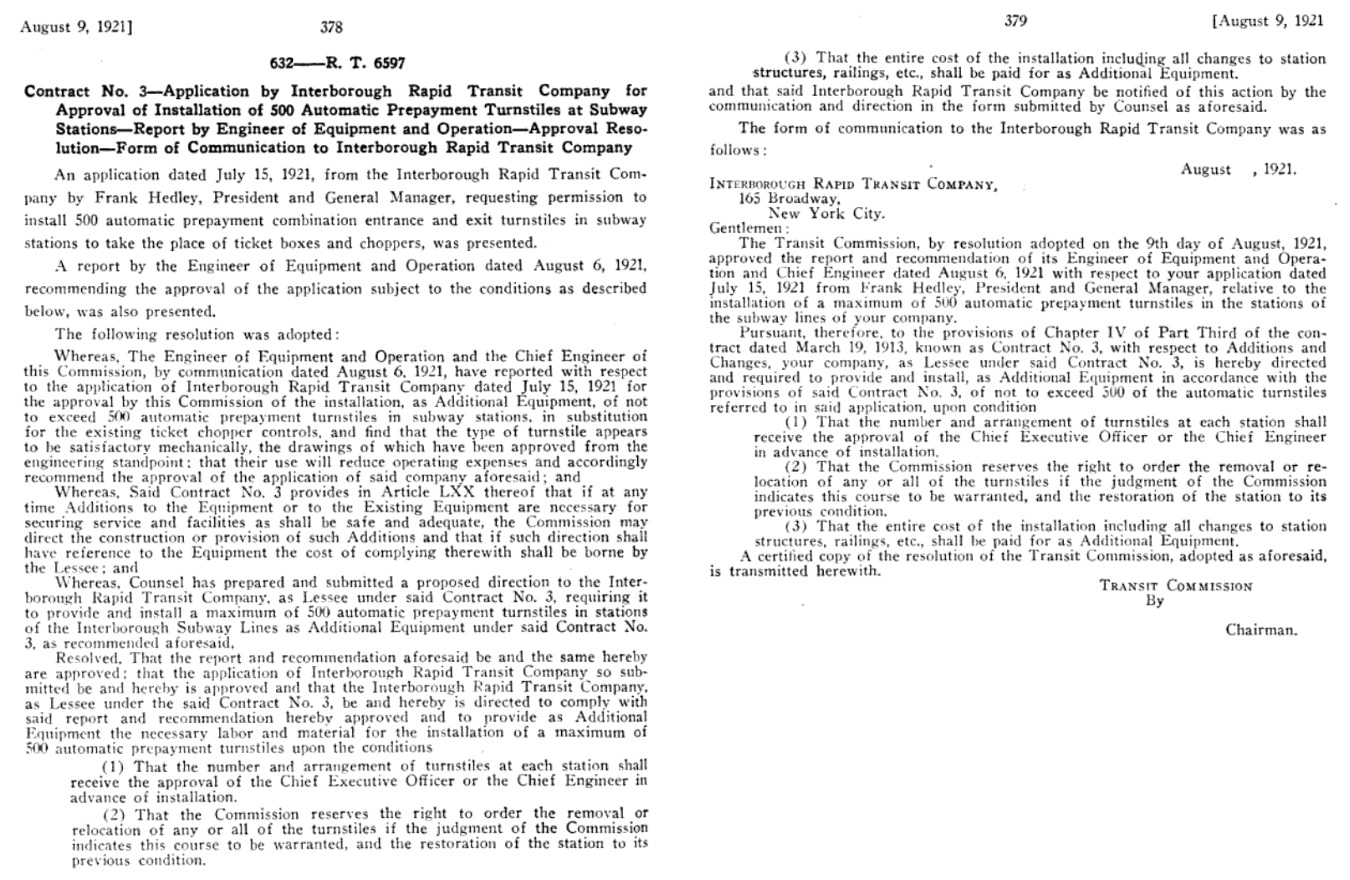

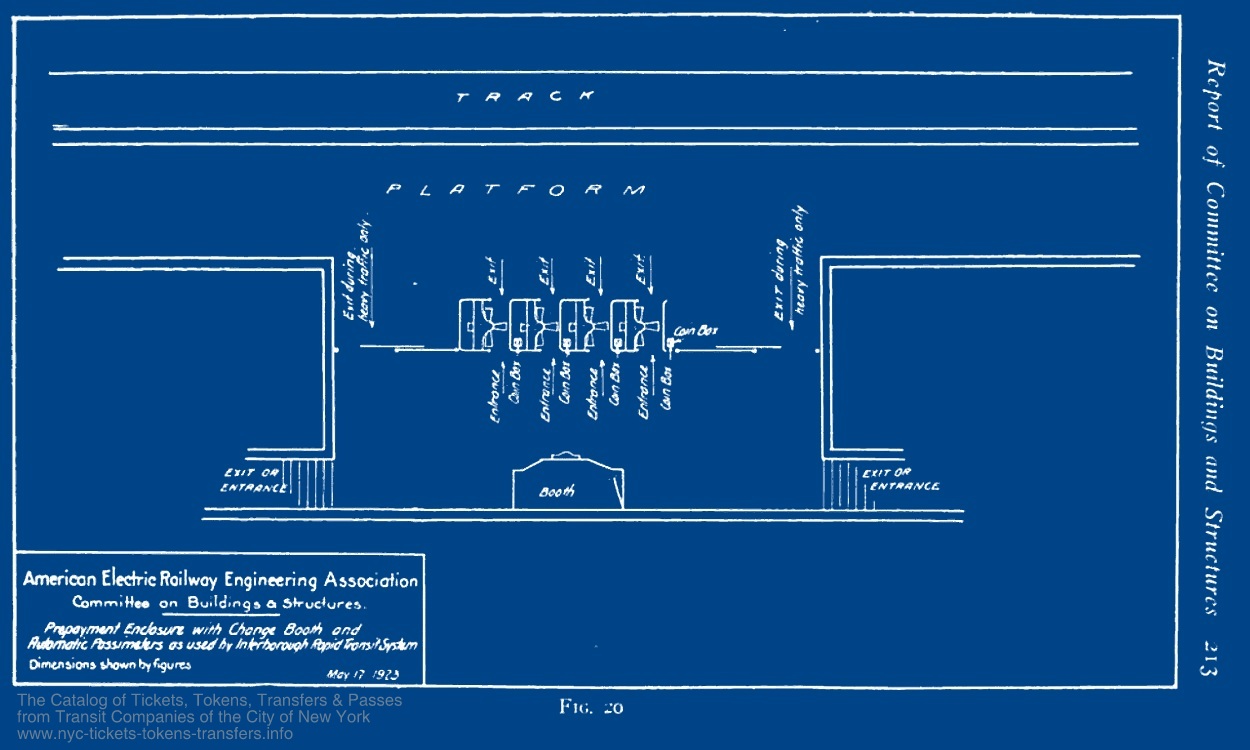

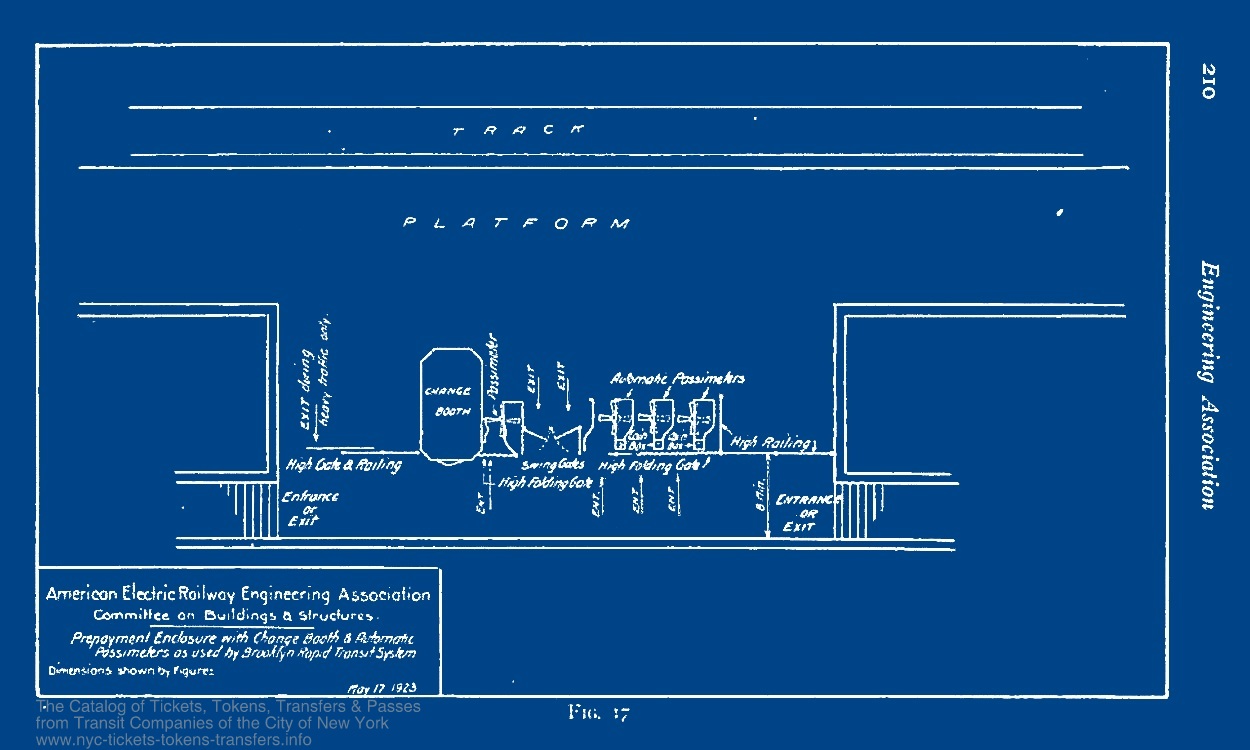

Some transportation companies opted to use tokens not as a

reusable transfer device; but as a primary admission method

via an automatic turnstile. When first introduced, it was known as an

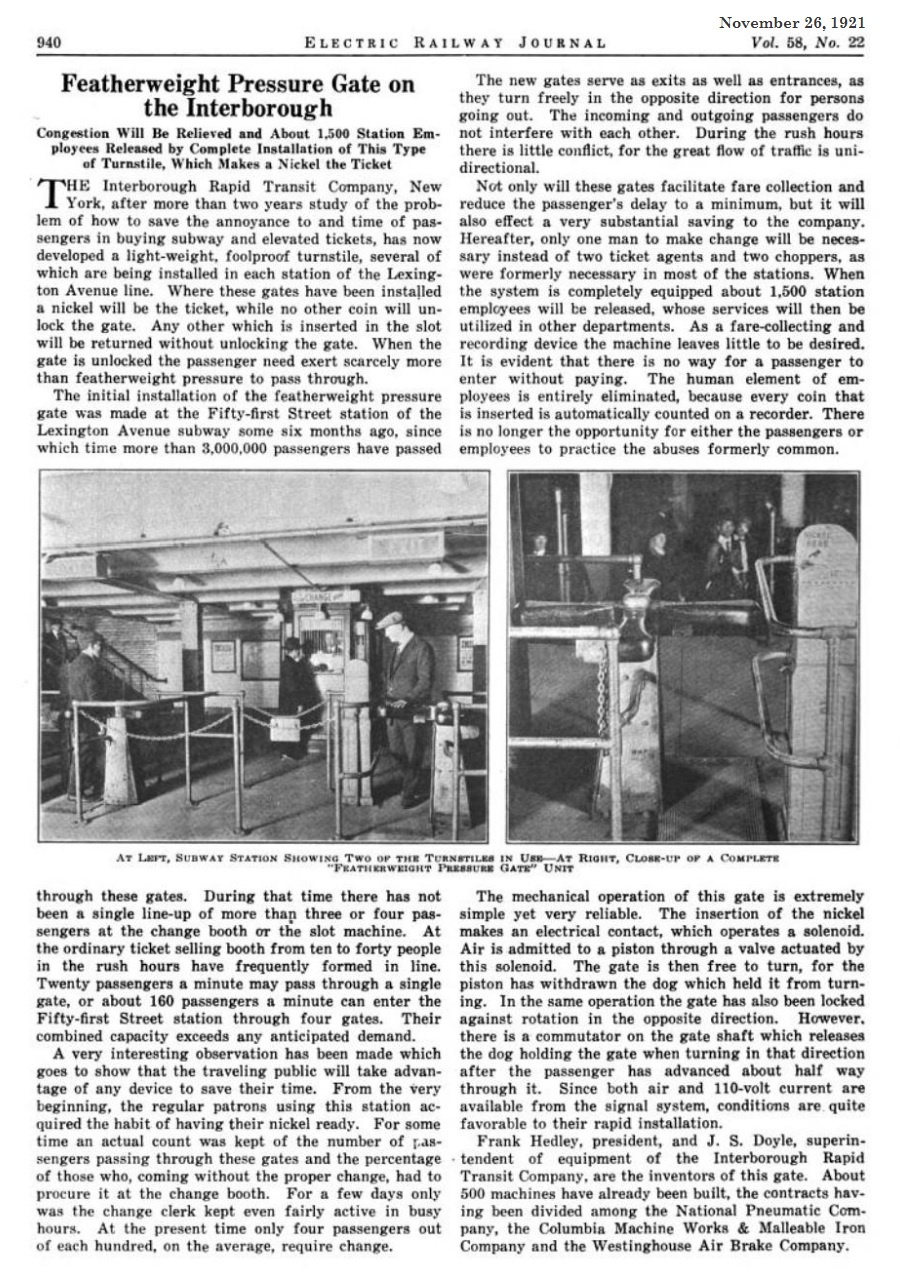

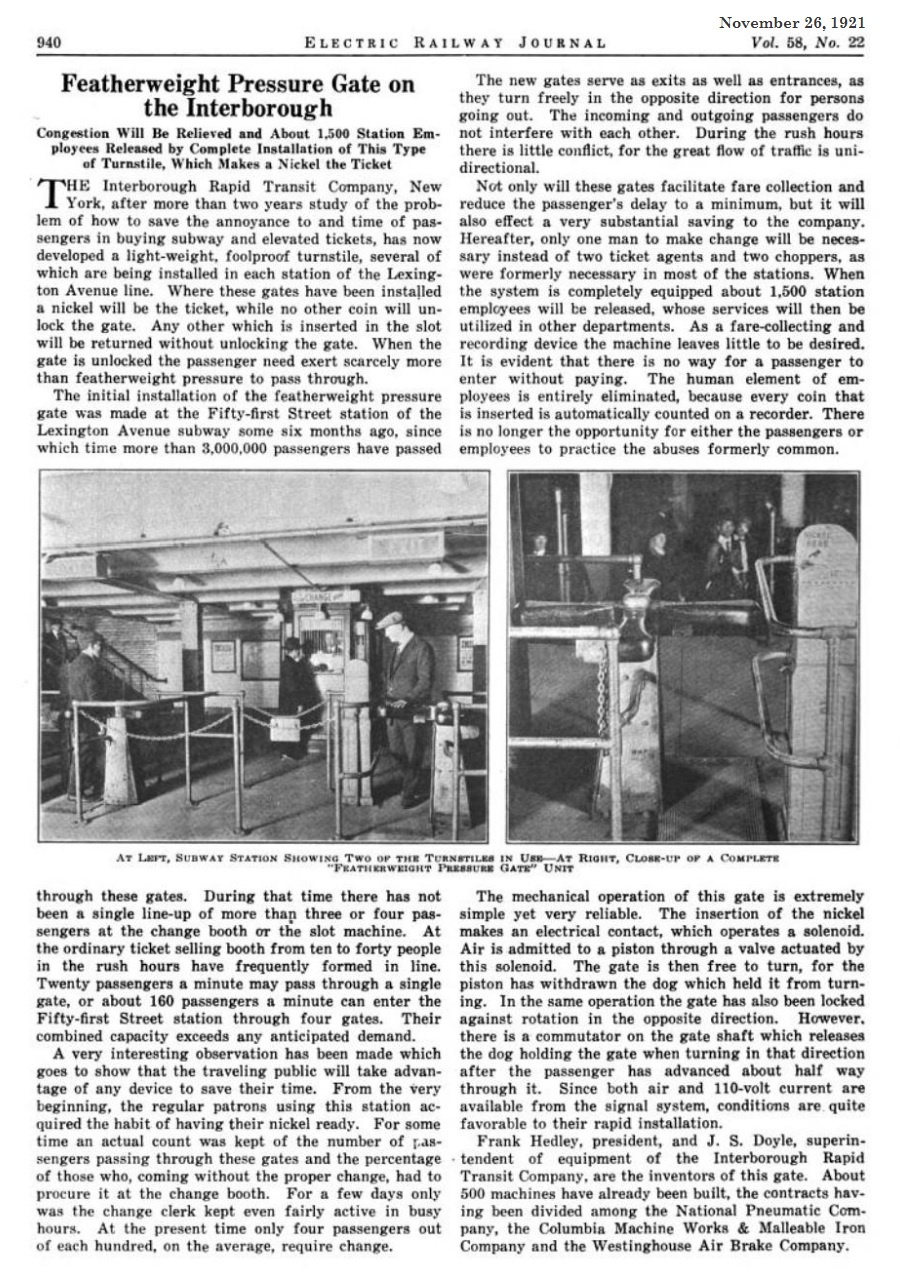

"automatic passimeter". Manually operated passimeters, actuated by the clerk; pre-existed the automatic type. These manually operated passimeters will be discussed a little later. The automatic passimeter became better known as the turnstile. US Government / Mint issued coins, and later on tokens that were accepted in turnstile applications; were always of metal composition. We will explain why, a tad later in this chapter. The first mechanical turnstile for the New York City subways and elevateds was not deployed until May 1921, and after being filed for a patent that same year, by Mssrs. Frank S. Hedley of Yonkers and James S. Doyle of Mount Vernon, NY. This first turnstile would be installed at the 51st Street Station on the Lexington Avenue Line. If these names happen to sound vaguely familiar, perhaps that is because Frank S. Hedley was the President and General Manager, and James S. Doyle was Superintendent for the Mechanical Department, of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company. Side note: it should be recognized that there were other patents issued for other designs of coin operated turnstiles prior to this one; but as this is the type installed in the subways, therefore it is this model we will be focused upon. |

|

The complete Patent Filing above can be viewed here: Turnstile Patent 1921 US1578660.pdf |

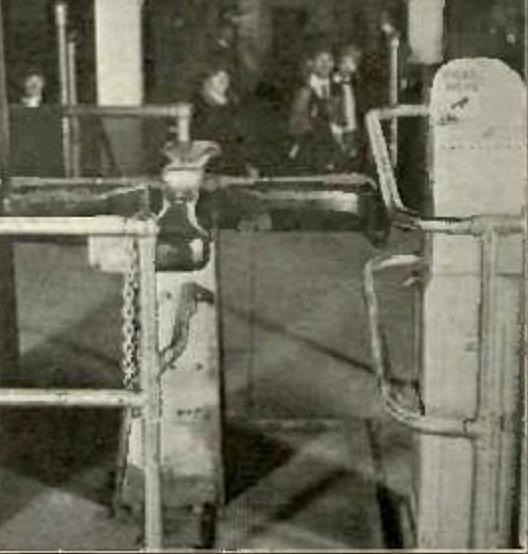

Electric Railway Journal - November 26, 1921 |

|

|

|

|

Last nickel: Ms. Carmen

Gherdol - June 30, 1948 - 11:59 pm

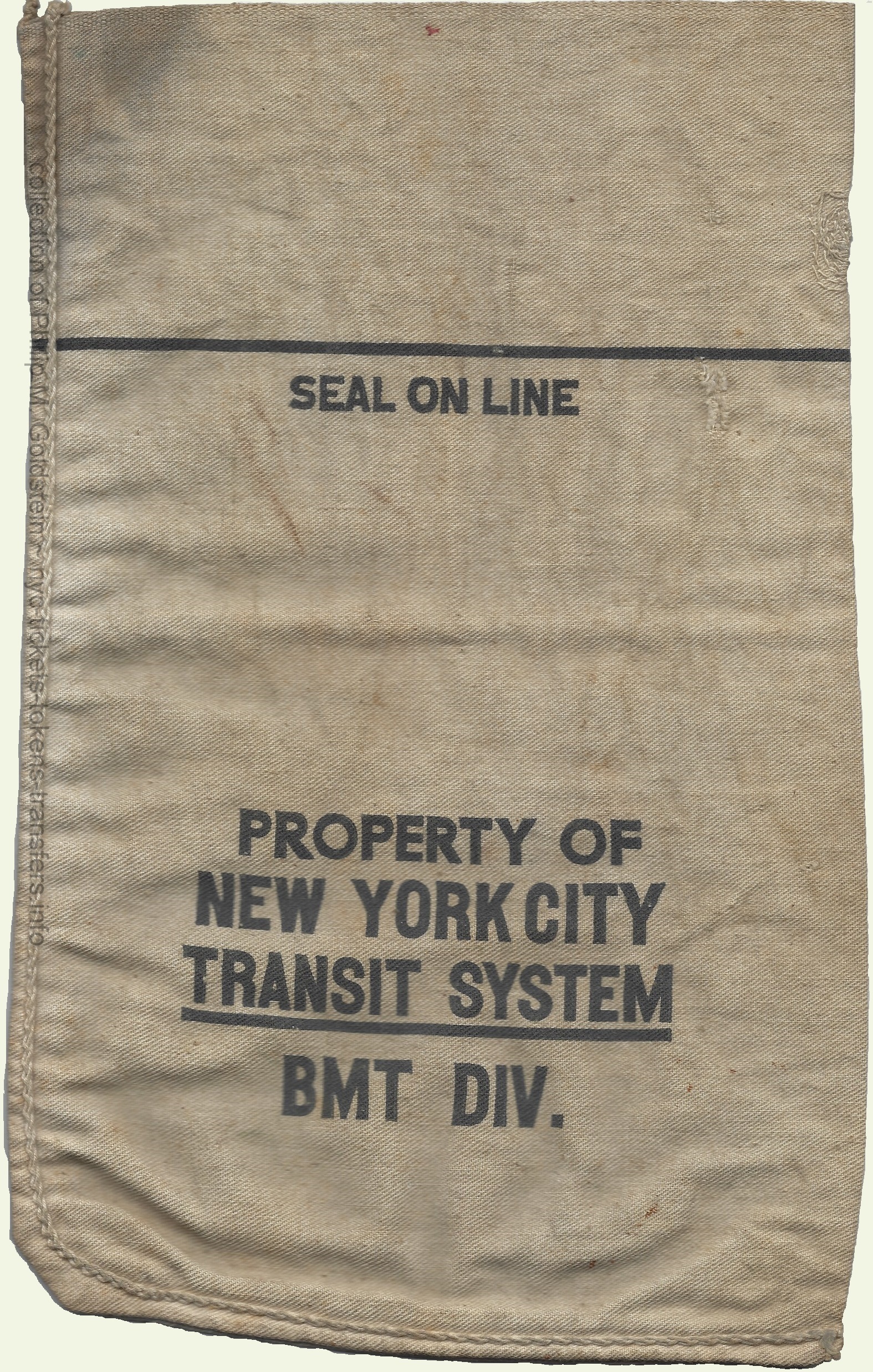

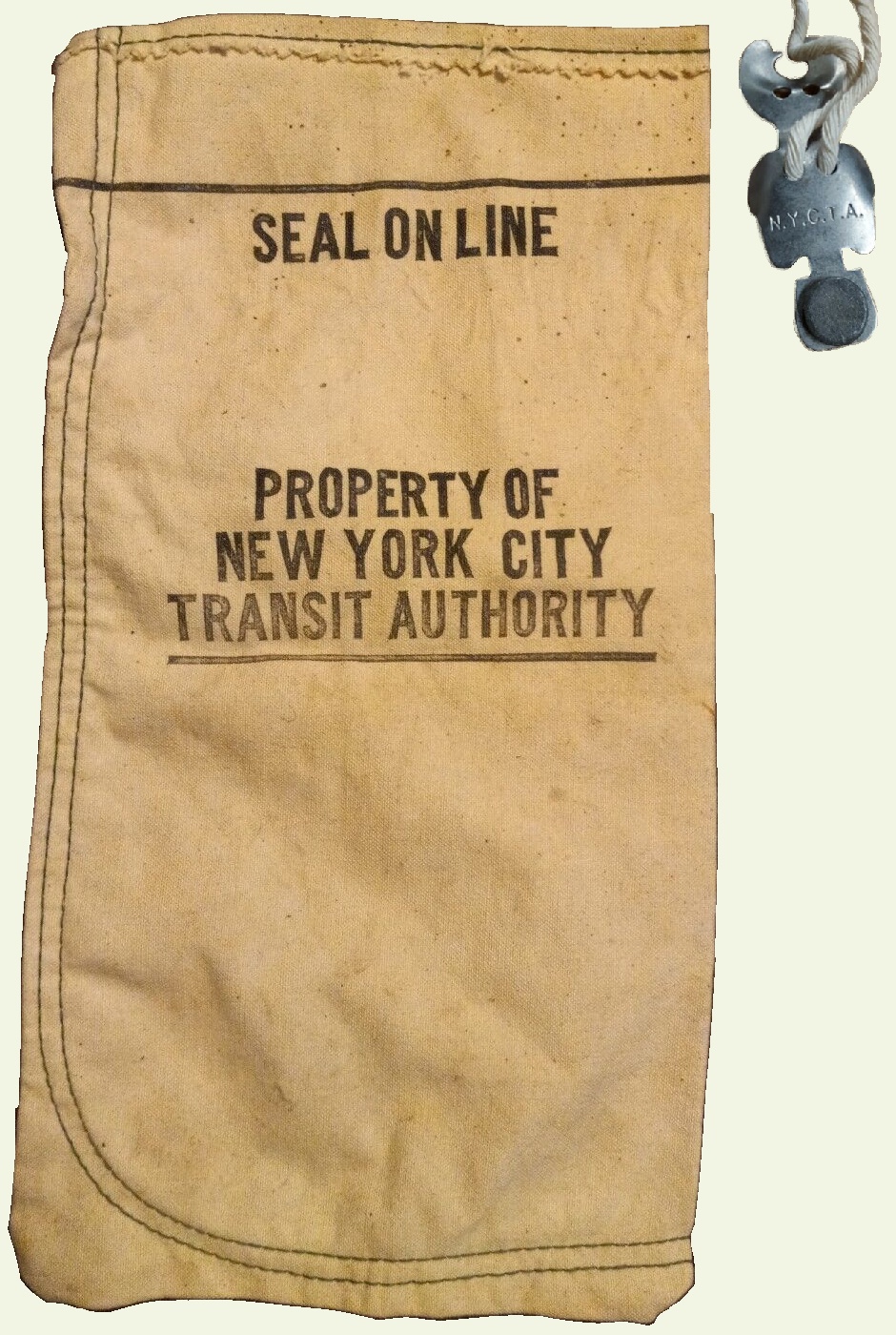

Assistant Supervisor Bartholomew Barry holds the canvas coin bag that will cover the coin drop. IRT Times Square Station image courtesy of the New York Times Digital Archives |

First dime: Ms. Esther

Pollack - July 1, 1948 - 12:00 am IRT Times Square Station image courtesy of the New York Times Digital Archives |

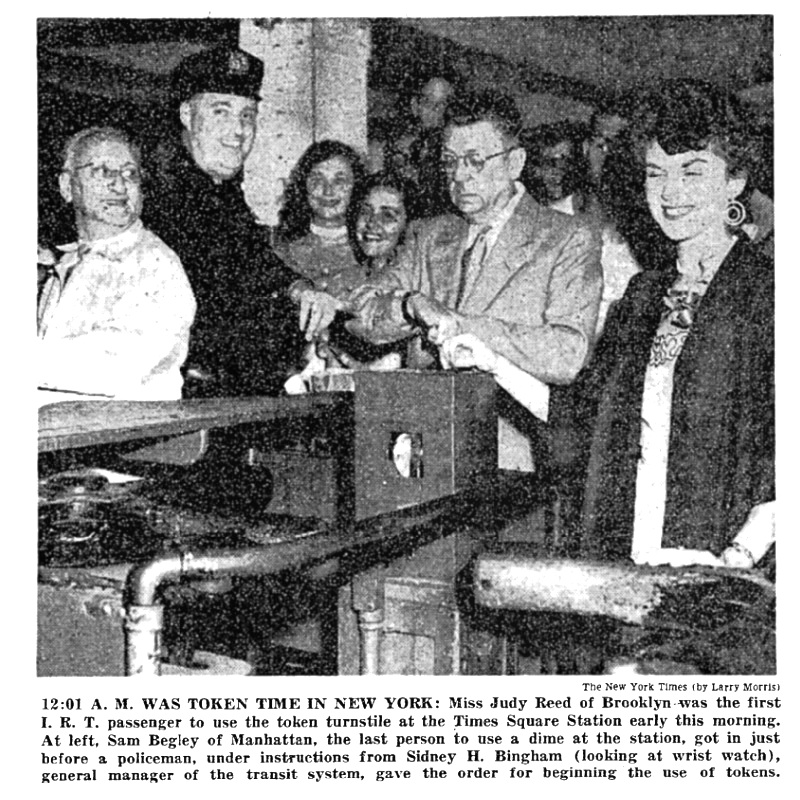

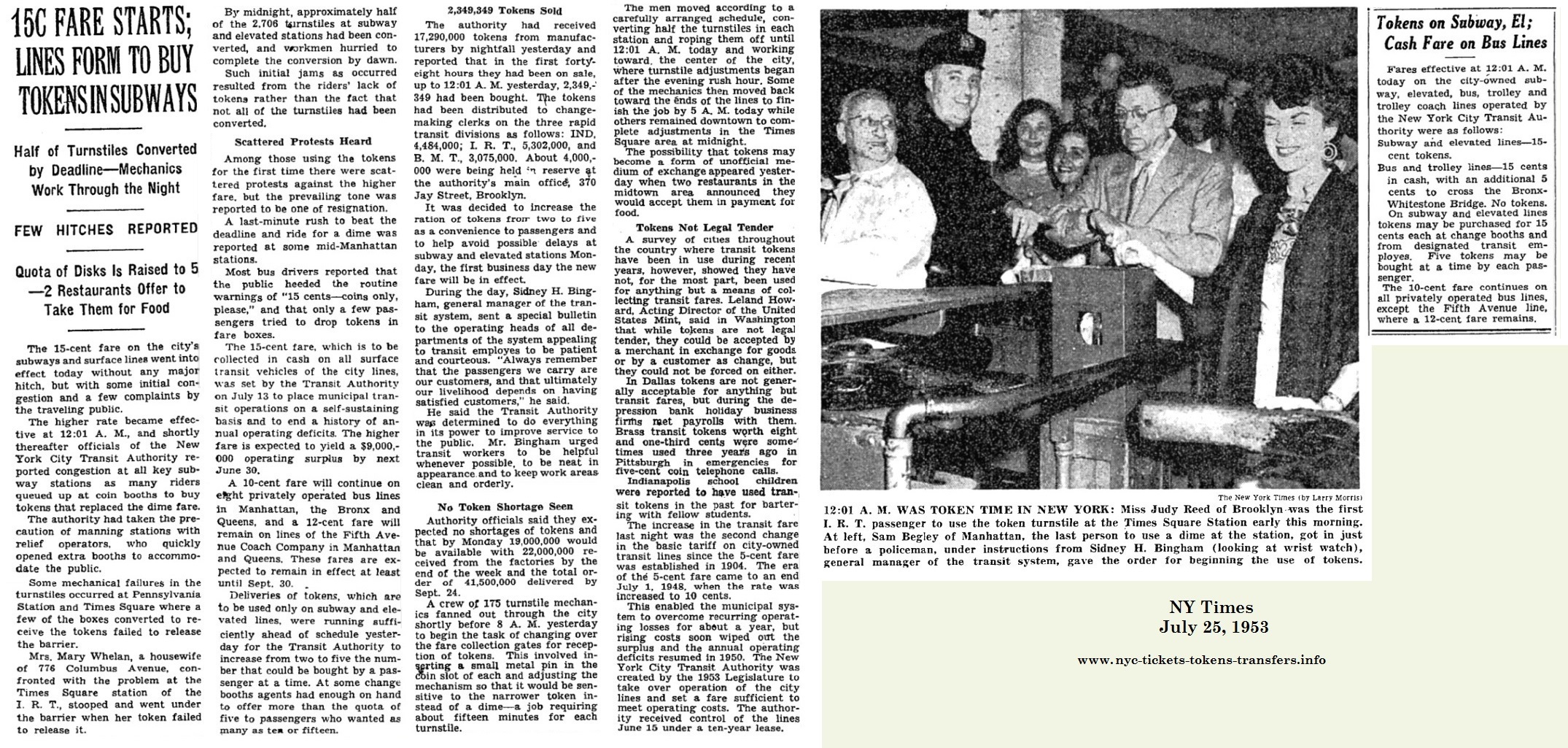

First 15 cent token: Ms.

Judy Reed - July 25, 1953

IRT Times Square Station image courtesy of the New York Times Digital Archives |

![]()

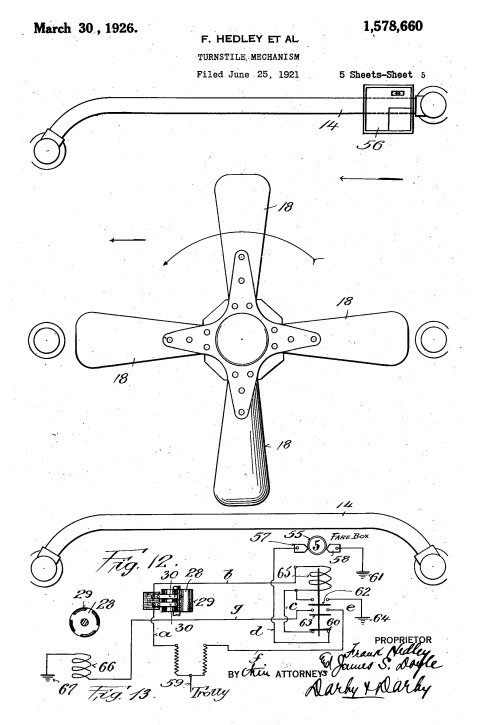

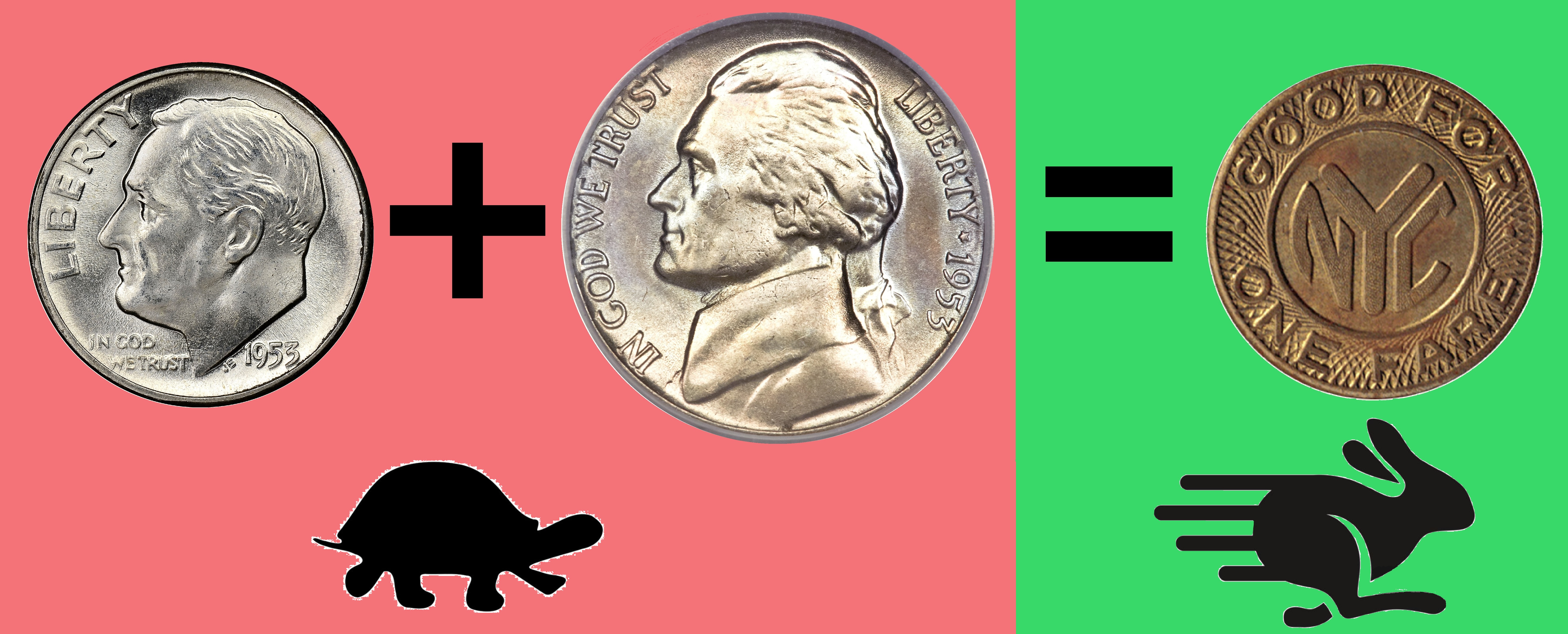

The 15 Cent Fare: Why a token and not coins?

| date | fare amount | maximum coinage | minimum coinage |

||||

| 1904 | 5¢ | 1 nickel | |||||

| 1948 | 10¢ | 2 nickels | 1 dime | ||||

| Had tokens not been introduced, the following coins would have been required: | |||||||

| 1953 | 15¢1 | 3 nickels | or 1 dime and 1 nickel | ||||

| 1959 | 50¢2 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1 half dollar2 | ||

| 1966 | 20¢1 | 4 nickels | or 2 dimes | ||||

| 25¢ | 5 nickels | or 2 dimes and 1 nickel | or 1 quarter | Please note: the NYCTA never collected a 25¢ cent fare - it went from 20¢ to 30¢. | |||

| 1970 | 30¢1 | 6 nickels | or 3 dimes | or 1 quarter and 1 nickel | |||

| 1972 | 35¢1 | 7 nickels | or 3 dimes and 1 nickel | or 1 quarter and 1 dime | |||

| 1975 | 50¢ | 10 nickels | or 5 dimes | or 2 quarters | or 1 half dollar3 | ||

| 1980 | 60¢ | 12 nickels | or 6 dimes | or 2 quarters and 1 dime | or 1 half dollar and 1 dime | or 1 half dollar and 2 nickels | |

| 1981 | 75¢ | 15 nickels | or 7 dimes and 1 nickel | or 3 quarters | or 1 half dollar and 1 quarter | or 1 half dollar and 2 dimes and 1 nickel | or 1 half dollar and 3 nickels |

| 1984 | 90¢ | 18 nickels | or 9 dimes | or 3 quarters and 1 dime and 1 nickel | or 1 half dollar and 4 dimes | or 1 half dollar and 8 nickels | |

| 1986 | $1.00 | 20 nickels | or 10 dimes | or 4 quarters | or 2 half dollars | or 1 half dollar and 2 quarters | or 1 dollar coin |

| 1990 | $1.15 | 23 nickels | or 11 dimes and 1 nickel | or 4 quarters, 1 dime and 1 nickel | or 2 half dollars, 1 dime and 1 nickel | or 1 dollar coin and 3 nickels | or 1 dollar coin, 1 dime and 1 nickel |

| 1992 | $1.25 | 25 nickels | or 12 dimes and 1 nickel | or 5 quarters | or 2 half dollar coins and 1 quarter | or 1 dollar coin and 5 nickels | or 1 dollar coin and 1 quarter, |

| 1995 | $1.50 | 30 nickels | or 15 dimes | or 6 quarters | or 3 half dollars | or 1 dollar coin and 5 dimes or 10 nickels | or 1 dollar coin and 2 quarters |

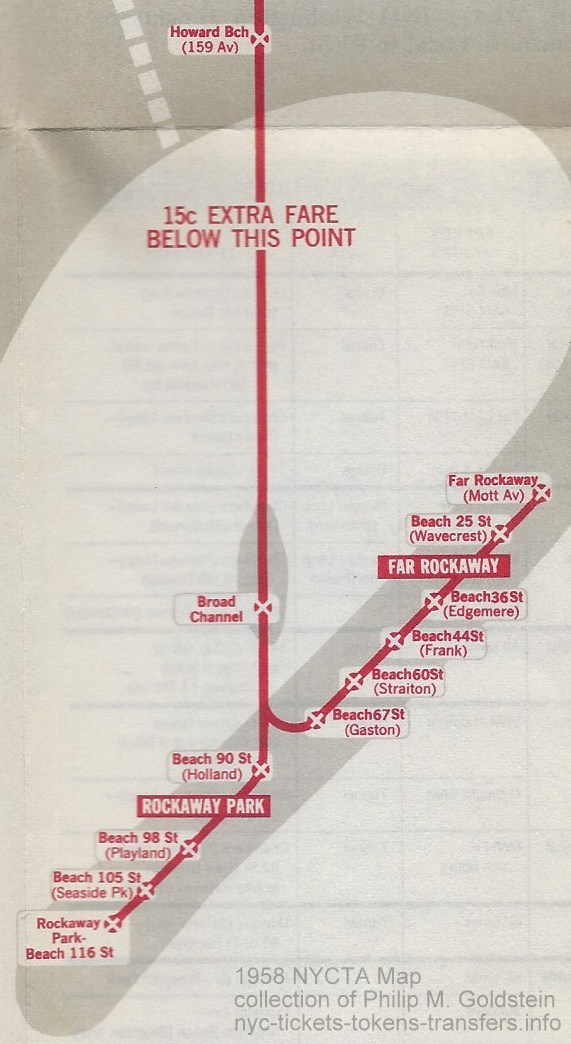

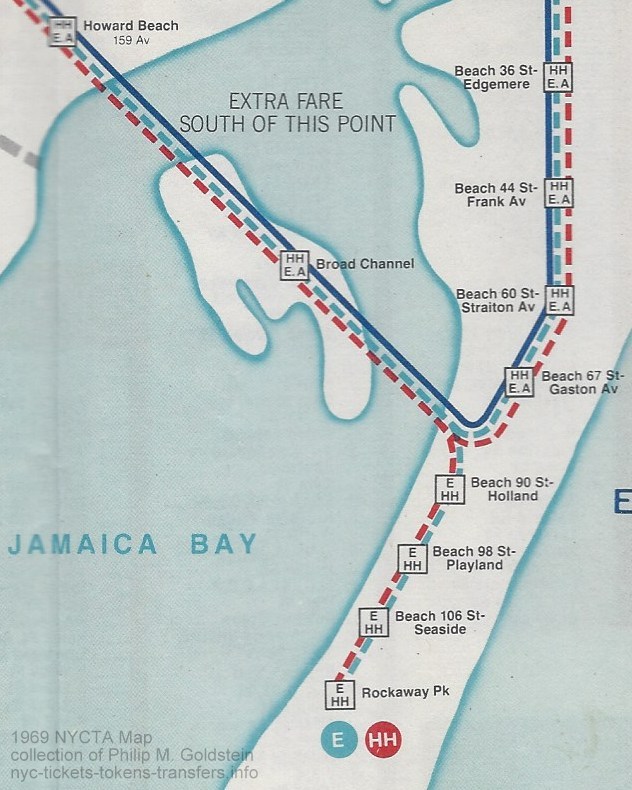

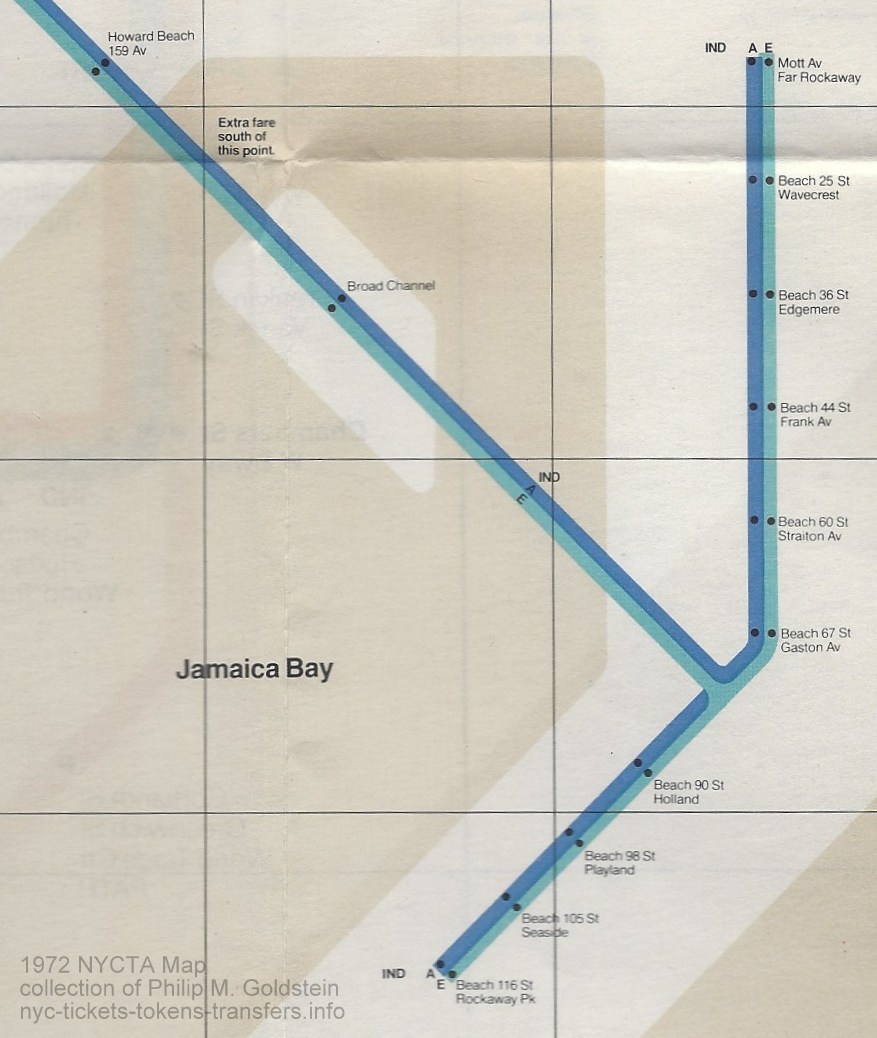

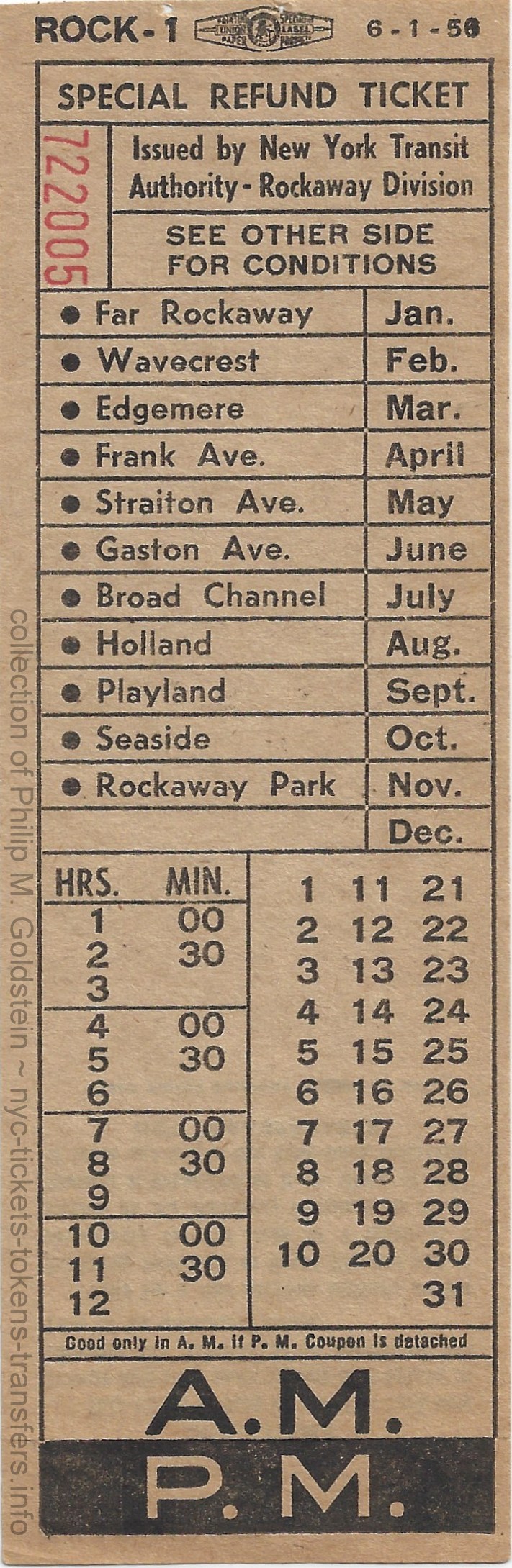

1 = Upon its opening in 1956, the IND Rockaway Line south of Howard Beach was a double fare zone. Therefore, double the fare amount and coins shown. This double fare was not abolished until 1975. 2 = In 1959, specially equipped turnstiles accepted half dollars only for the Aqueduct Racetrack Special Train. Patrons of the Aqueduct Special either brought their own half dollars or obtained them from a clerk at the two stations where the Aqueduct Special departed from: 42nd Street & Port Authority Bus Terminal or Hoyt / Schermerhorn Streets 3 = As far as is known, the NYCTA did not accept half dollars in bus fare boxes. Only token dispensers and token booths accepted them for payment (with reluctance). |

|||||||

.

.

|

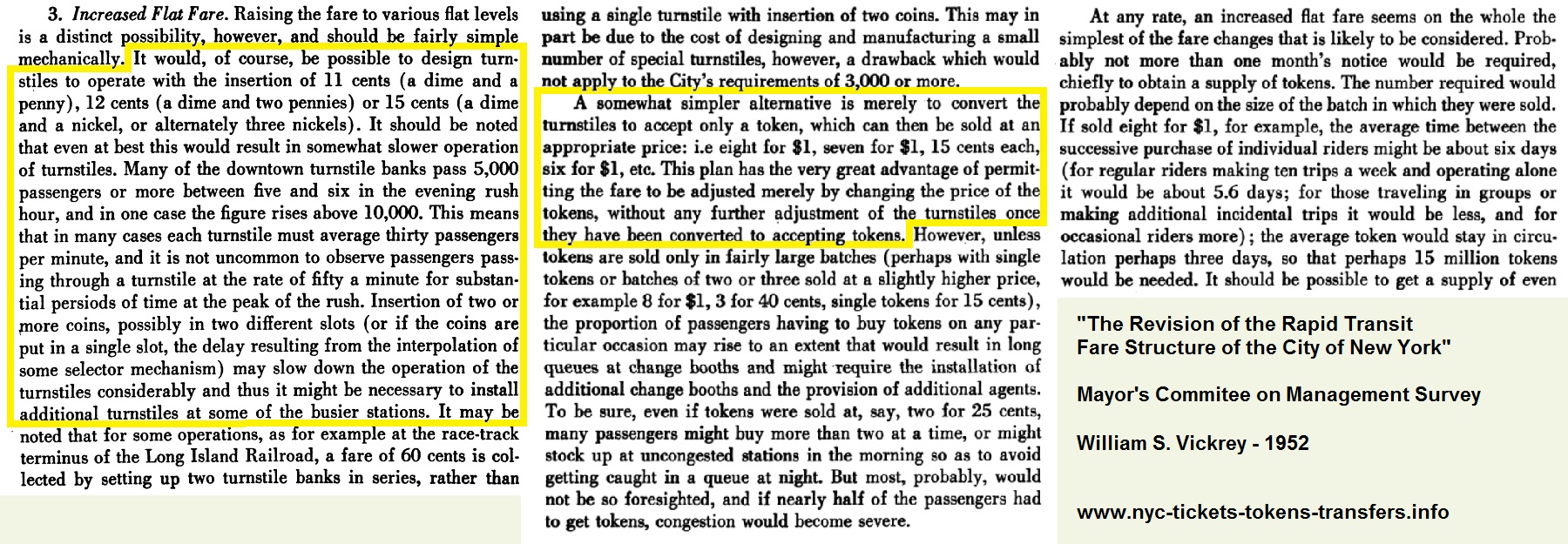

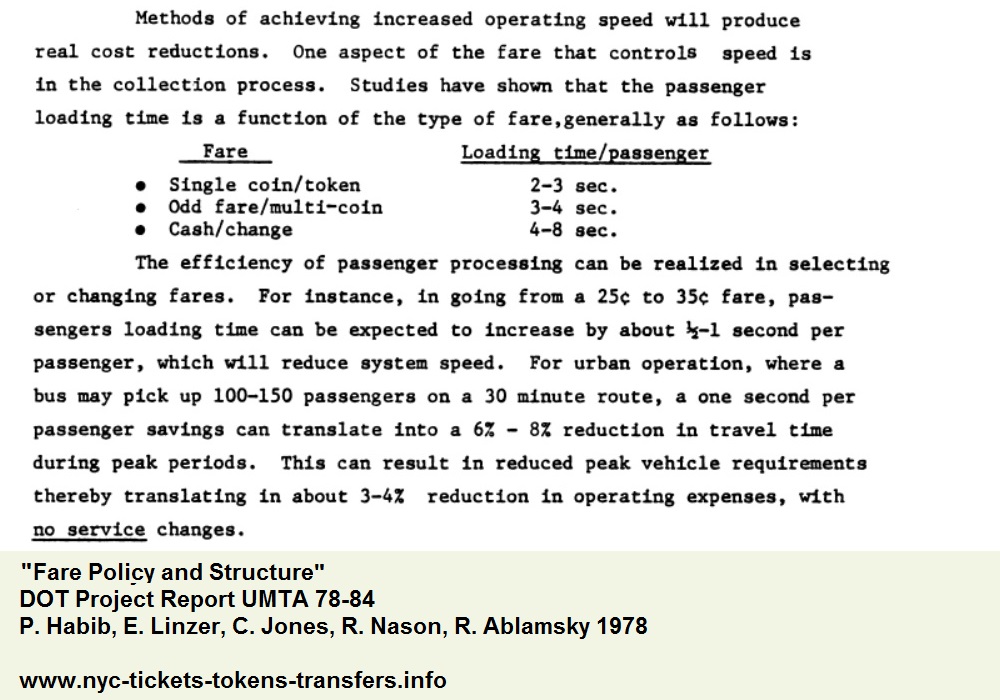

The second factor to be considered, and yet which is hardly (if at all)

discussed in regards to transit payment systems, is the speed of payment. Here, were are not discussing the time it takes to go to the clerk and get nickels, dimes or tokens for the turnstiles, but the time it takes to deposit the coin or token into, and proceed through the turnstile. In a usage application where speed is not of the essence, such as vending; obviously speed is not crucial. But when in regards to high speed - high volume usage such as those of rapid transit transportation, especially in large stations or terminals; and / or at peak times, any delay in paying at the turnstiles hindered the flow of pedestrian traffic. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It should be noted, that in reference to the New York City Transit System; that the periods of time that are considered weekday "rush hours" have grown steadily over the last 145 years of rapid transit ridership:

Not only has the amount of the workforce commuting to a more centralized area in Manhattan resulted in increasing transit users, but there has been a trending shortening of the work day 10 am to 4 pm, which has altered the periods of rush hours. Thus, during these periods of "rush hours", any delay in depositing the coin or token by a single passenger at the turnstile had an consequential effect on following passengers. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| "The Revision of the Rapid Transit Fare

Structure of the City of New York" - Mayor's Committee of Management Survey William S. Vickrey - 1952 |

"Fare Policy and Structure"; DOT Project Report UMTA 78-84; Habib, Linzer, Jones, Nason, Ablamsky, 1984 |

From these documents, we can extrapolate that during rush hour, a single turnstile can see one actuation every two seconds (or 30 people per minute / 1800 people per hour.) As most large stations and terminals have at least 3 to 4 turnstiles or even more, this gets us to the figure of 5400 to 7200 persons per hour (turnstile actuations), per station. Also as stated, the turnstile actuation rate has even been recorded as high as 50 passengers through a single turnstile per minute, or 1.2 seconds per actuation; and a remarkable testament to the reliability of the mechanisms, and the simplicity in payment which permit this traffic.

By contrast, the WMATA (Washington DC Metropolitan Area Transit Authority) utilized turnstiles that accepted multiple coins, due to a zone / distance based fare system. These turnstiles, while they saw nowhere near the same level of traffic as the New York City system due to both a smaller population and smaller transit system,encountered a significantly slower rate of payment as well as increased actuation failure rate.

.

The principal of K.I.S.S. and we're not talking about the rock band! ![]()

In payment of a fare, inserting a single object into a single slot, was the epitome

of

the acronym: K.I.S.S. "Keep It Simple Stupid."

The K.I.S.S. principal, suggests that most systems and designs work best when they are kept simple, rather than made overly complicated. This means a focus on clarity and ease of understanding over clever, sophisticated solutions or multiple choice decision making.

It had been discovered through multiple generalized studies regarding time, motion and efficiency; beginning with Frank B. Gilbreth in 1912; and more specifically in regards to fare payment, that when it came to users (payors, passengers, etc) of mass transit, having to deposit a coin or token to enter through a turnstile, the use of multiple coins significantly increased the time required to go through said turnstile. In other words multiple coins "slowed down the works."

In a multiple coin slot system, the user in having to place the correct coinage in the correct slot requires a thought process: "place the dime in the small slot, the nickel in the big slot."

With

the single coin or token, it became more of a second nature - a pre-programmed

mental conditioning: insert nickel/dime/token, push. Even for non-commuters, i.e. the tourist; it was simple.

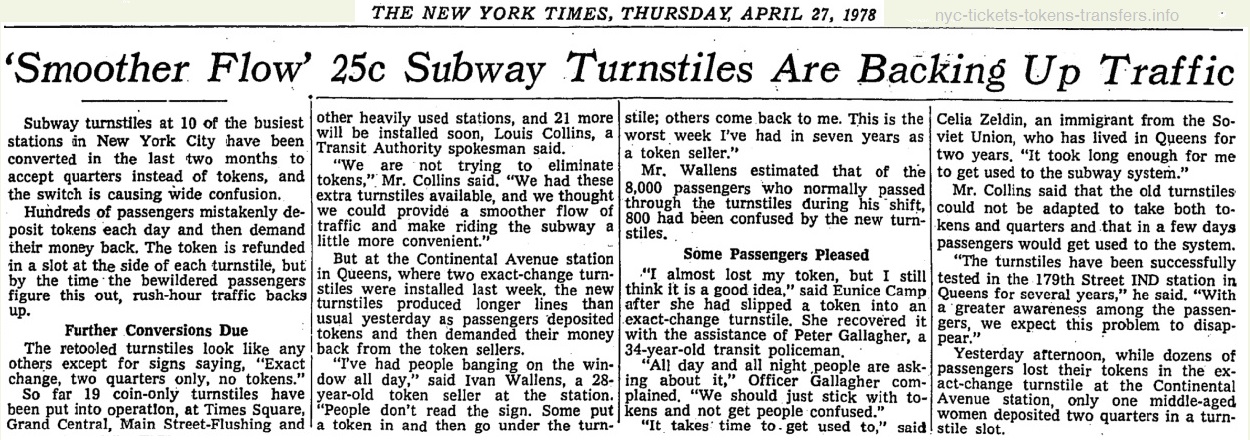

| Studies showed multiple coins slowed down the

process of passengers paying and transiting through the

turnstile. Ironically this very problem and the research behind this issue appears to even been forgotten (or taken a back seat to convenience) and would be encountered once again in 1978. This was when the New York City Transit Authority attempted to implement turnstiles that accepted coins and / or tokens for convenience with the Duncan Industries Model TC "Token - Coin"; which accepted two quarters or a token for the 50 cent fare. The issue encountered with these turnstiles was determined to be that many payors kept placing the wrong object in the wrong slot; re: placing the token in the quarter slot. |

|

Furthermore, persons handling more than one coin, especially doing so in a hurry (hence rush hour), thereby increased the chances of that person fumbling and dropping one or both of the coins on the floor, requiring them to stoop down and retrieve said coin(s) - IF they did not roll far or beyond the turnstile. If this occurred, then the payor needed to dig out replacement coinage from pocket or purse.

For comparison, think back to old payphones where there was a opening for a nickel, dime and quarter. If you were calling a local telephone number, a nickel or dime (and later a quarter) made your connection. One coin - ding - dial tone. But when you had to make a long distance call, and required varying amounts of change; you couldn't hold but more than a few coins at once in your hand. And no matter how many coins you could "palm" (hold in the palm of your hand), it took a few seconds to manipulate the next coin to your finger tips to deposit that coin into the slot. Most people put their coins on small metal tray in front of the phone and deposited the individual coins one at a time. This was not an option in the fast moving subway turnstile.

In a rapid transit (subway or elevated) setting ("rapid transit") however, a single turnstile at peak travel time (the rush hours) could see one person depositing a coin or token every two seconds; which equates to 30 per minute; especially at major stations and terminals. Watching the following archival WPIX news flim footage of people going through the turnstiles in a New York City subway station. At the 1 minute 22 second mark; one will witness a smooth, uninterrupted procession of one person to the next.

Matter of fact, you can even see "a fumble" where a passenger missed the token slot but quickly recovered the token. Using a stop watch, it only takes 1.8 to 2 seconds from the time the token is deposited by the leading person and for that person to walk through, to the second person depositing their token and repeating the process, and this was not rush hour.

Therefore, the introduction of multiple mechanisms and / or multiple coin slots in a turnstile; increased the likelihood of a misfed coin or token, which in turn resulted in rejection and failure to release the turnstile. Multiply this by the number of turnstiles at a busy station, and it would equate to a recipe for unwanted delay.

In a turnstile admittance system with slow moving pedestrian traffic such as those used for admission to libraries, museums, cafeterias, et al, this lack of speed was not much of a factor. But when in relation to New York City rapid transit (the subway and elevated system), reliable operation of the turnstiles equated to speed of the payment and admission process.

This speed of payment was conducive to mass transit system where hundreds of thousands to millions of people moved through the system daily like in New York City.

As such, the single coin or coin-like object, whether it be a single nickel, dime, quarter; or a token; equated to speed. Multiple coins or choices slowed down the works. And in the New York City subway, this would not do..

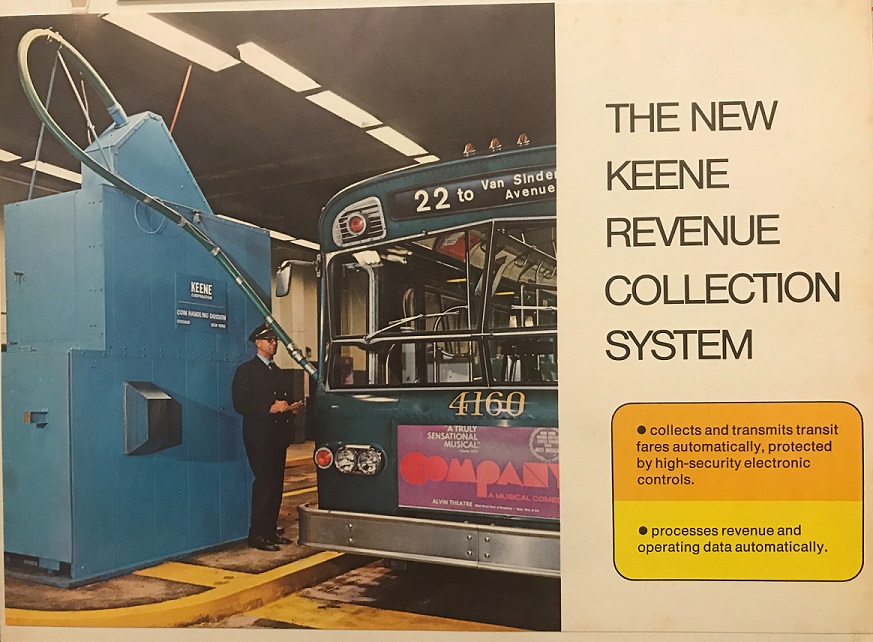

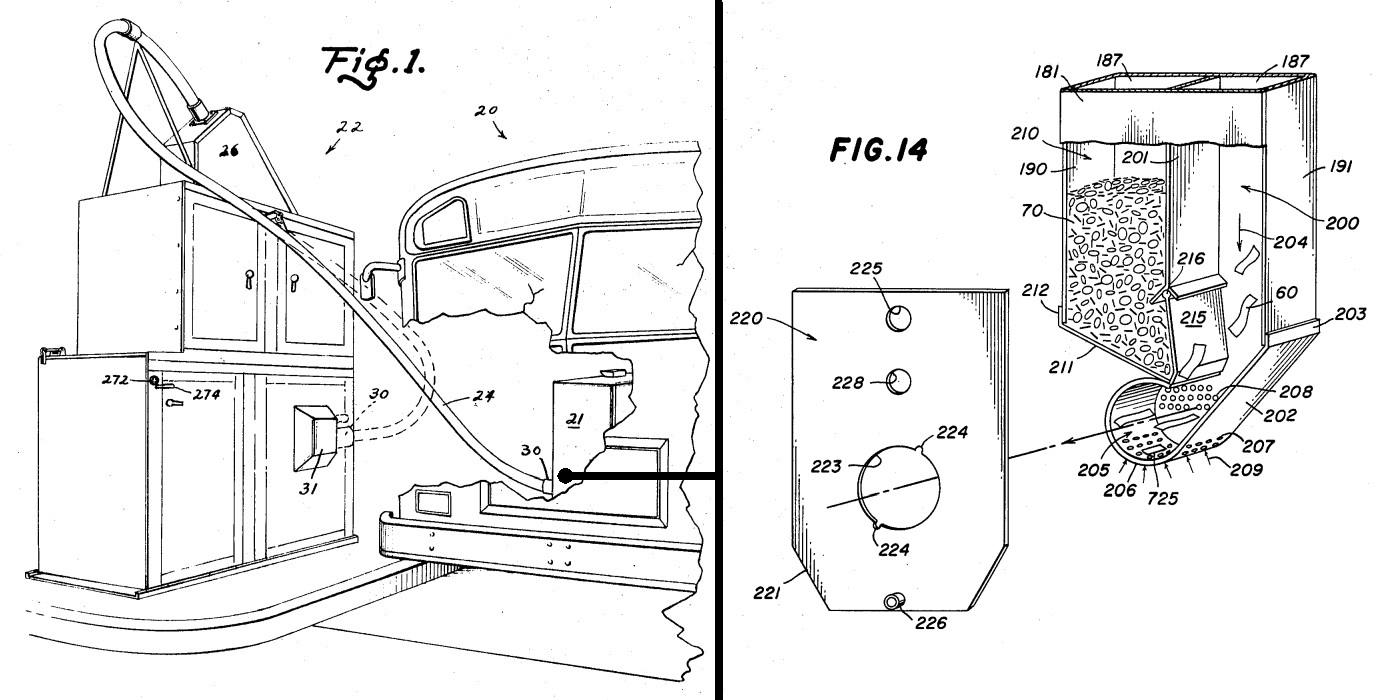

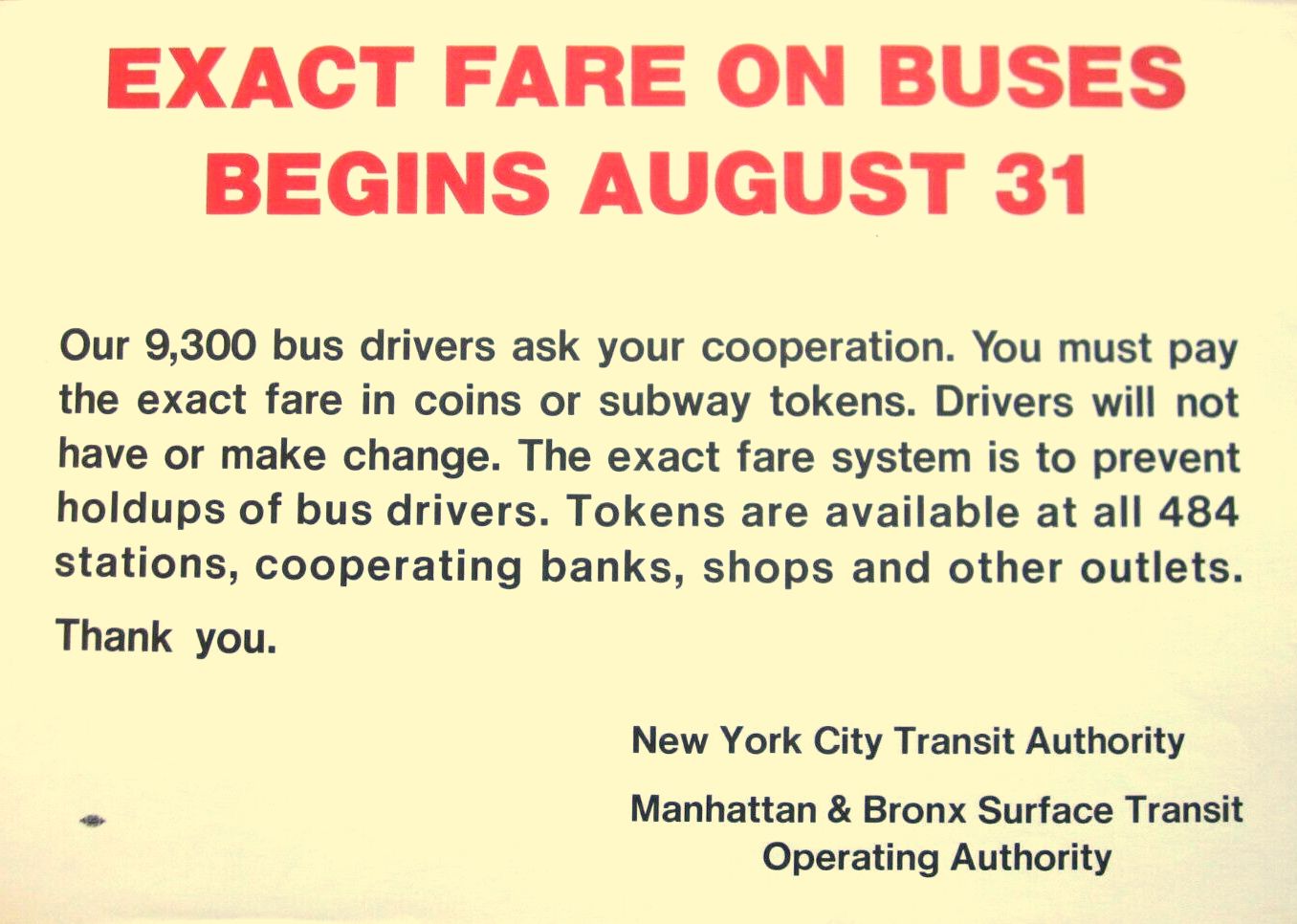

Speed was not as crucial on surface transportation

Payment speed was not as much of a factor on surface transit methods, i.e: streetcars / trolleys and / or buses. It must also be remembered; New York City Transit Authority tokens were NOT even accepted on buses or streetcars until May 18, 1963 - almost 10 years AFTER tokens were introduced for the subway. With streetcars & buses, it was generally accepted that the prevailing fare would be paid by combinations of coins or a token in later days, with most people conditioned to have the change ready as the bus approached.

The reasoning for this was, stemmed from either the trolley conductor (or in later operations the bus operator); would be present and made change (until 1969) and could remediate fare payment problems; and whereas some people required a transfer or directions for a connecting bus; the payment process was inherently slower.

Another factor inherent to surface operations; was the 2 or 3 cents most companies charged for a transfer to another line. So here, we now have pennies added to the equation of coins needed on a streetcar or bus, either furnished by the passenger at time of purchase of the transfer, or received by the passenger in change from the conductor / operator.

But also, even during rush hour / peak travel times; at best a single bus of the 1950's era only saw a capacity of approximately 40 to 60 people at a single time, and the boarding process was slow enough a passenger could deposit the mix of coins into a fare box built with a sorting mechanism, which took five to seven seconds per passenger: one person at a time, steps up onto the bus, change at the ready to deposit into the fare box and the driver visually verifying the drop of coins before pressing the accepting lever.

Speed, in Advance

Another positive attribute to token use, is such that token operation lends itself very well to prepayment. A pack of ten tokens is significantly less cumbersome than say a roll of 40 or 50 coins of equal value to the tokens, and can be sold in advance.

Pre-payment also has an added benefit for the transit agency (i.e. the NYCTA) is holding ones money in advance, instead of that person holding their money. Say a transit passenger purchased one token at a time; the agency only sees minimal investment and still has to pay the clerk wages to dispense a single token.

But if a passenger purchases ten tokens in advance, and the transit agency held onto the monies from the balance of nine tokens not used at moment.

And, say in the case of a tourist or short term visitor to New York City, and of whom purchases a ten pack (or an unlimited MetroCard); and departs before using all ten tokens (or the full value of the MetroCard) - the transit agency sees a windfall. They get to keep that money. Those tokens or fare card are only good for that particular transit agency and no where else (except in cases when used as a slug); whereas US coinage could be used all over the country, and any business or bank. There was no incentive to "purchase" US coins ahead of time, and even if there were; you could get rolls at any bank and most large businesses for no charge. You held the full value until used.

.

An added benefit of tokens was a security issue: a change in the size slot on the turnstiles could not take place to deter prevent slug use in regard to US coin usages; which was standardized and widespread. Whereas in regard to tokens, the single token size could be changed to discourage and prevent the of using slugs. If an increasing amount of slugs or counterfeit tokens was realized; a new smaller or larger, or thicker token could be released superceding the old type.

This could not be done with US coinage because of their nationwide or worldwide remittance factor.

Hence the decision by the New York City Transit Authority to implement the token as a solitary device for fare payment and general admission for fares of that required more than a single coin.

As tabulated by the Rail Transit Fare Collection Policy and

Technology Assessment, December 1982 DOT Urban Mass Transit

Administration (Govind K. Deshpande, John J. Cucchissi, Ronald C. Heft

(Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Page 26); the ratio of failures in the

Perey Turnstiles in the New York City subway system averaged 1 failure

for every 45,000 actuations. This was an impressive figure,

and as

noted in the publication, as other and smaller municipal transit

operations with multiple payment options suffered significantly higher

failure rates at the turnstiles.

|

Rapid transit = rapid fare payment. So yes, in

this

hyper-fast paced world of fare collection

on a mass transit system; the single token was the sane choice. Simple.

Secure. Durable. Versatile. Reliable. Convenient. And cost effective

for the issuing agencies. Accepting multiple denomination of coins at the turnstiles meant more coins to process which meant more complicated mechanisms. If the turnstile had room for a sorting method, that meant three holding tubs. Nickels dimes quarters and tokens. Not enough room, meant all the coins in one tub, to be sorted by the clerk which equates to time consuming sorting at end of shift. Using one token kept the mechanism simple and its reliability high and the coin sorting took place intermittently and at time of purchase, instead of all at once at end of shift.. Furthermore, with subsequent fare hikes, the size or magnetic property of the token could be changed to prevent the hoarding of, and prevent the use of lower value tokens. Furthermore, it was a security measure as well: changing the size or properties of a token prevented older generations of slugs from being used via a new size token. Even with the advent electronic fare payment systems with the Metrocard, glitches were encountered. When the MetroCard was first introduced in 1997, the premise was the same - a single swipe of a plastic card was supposed to allow activation of the turnstile mechanism. However, it was soon discovered that a bent or creased plastic card, or a card that had been near a strong magnetic field (i.e.: laid on or a near a computer, or a speaker) had corrupted the embedded magnetic strip. Either of these conditions caused the cards not to read properly, if at all; and failed to release the turnstile and allow the payor through. This required the user to swipe more than once, with each swipe taking a few precious seconds; with waiting passengers lining up behind them. These glitches "choked" the turnstiles, and slowing down pedestrian traffic through the turnstile. |

|

![]()

|

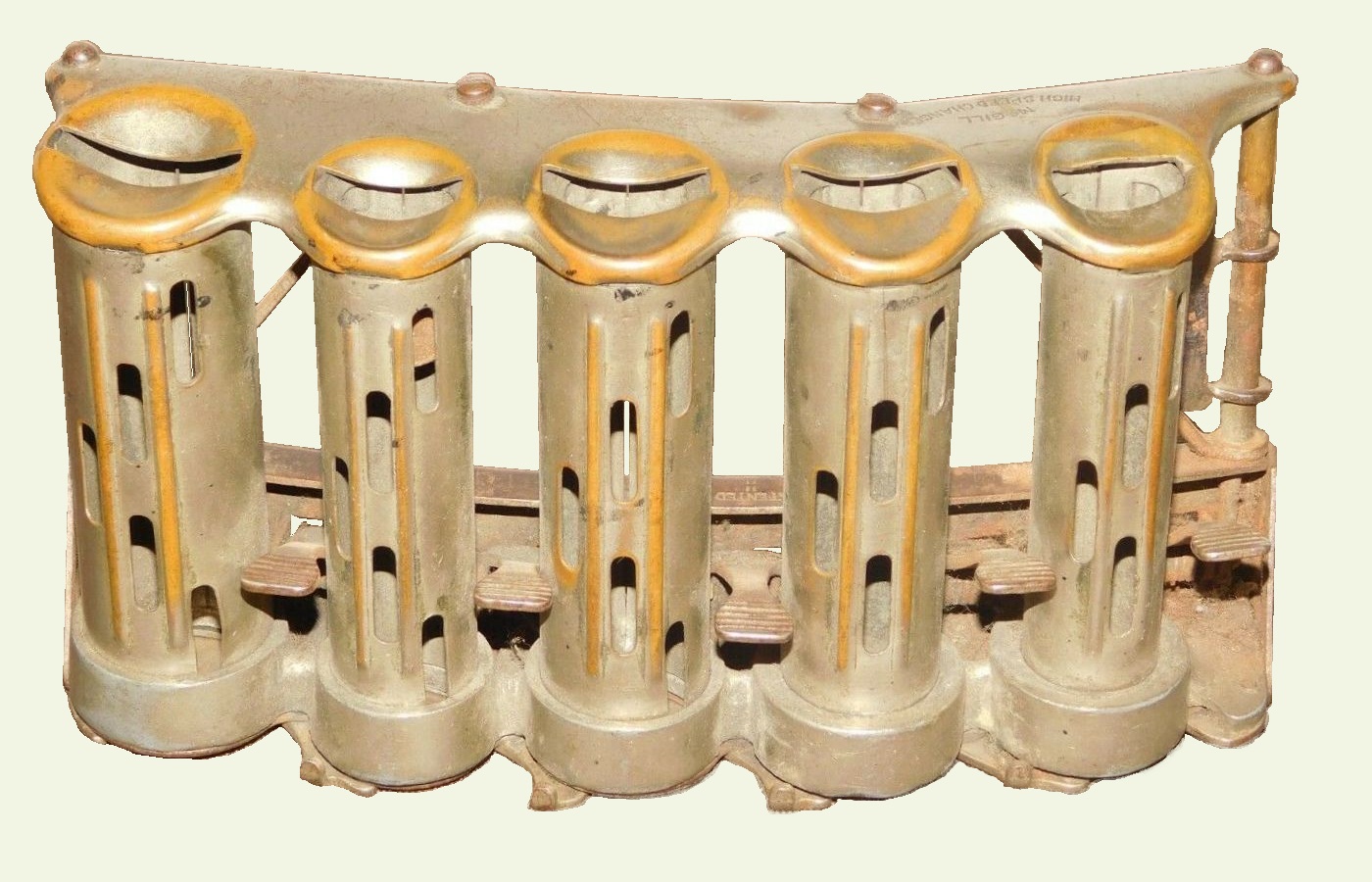

Until

1969, the method of collecting fares on trolleys /

streetcars and buses was a little different than on their rapid transit

counterparts. When you boarded the trolley / streetcar, you either paid the conductor; or in growing cases of one man operation after 1930, you paid the motorman / operator / driver. But whomever was in charge of actually collecting fares, they would be able to make change as well. As such, they had a portable coin changer (an example of which can be scene at right), and of which was clipped to their waist band as can be seen in the photograph at below right. This coin changer was part of their regular duties and uniform "kit". Coin changers could have four, five, six or even more "barrels", the number of which depending on the denominations of coins that were accepted, and that needed to be given in change. Usual configurations were one for pennies, two for nickels, one for dimes, and one for quarters; or one penny, one nickel, one dime, one quarter and one token. Custom coin changers could be ordered if the conductor only needed to handle minimal types of coins: say, only nickels and tokens. Furthermore, if you required a transfer to a connecting line, you paid the extra fare (usually 1 or 2 cents) and were issued a specially marked token (as mentioned in the chapter above) which would be kept in one of the barrels of the coin changer or a cardboard ticket (mentioned in the chapter below). Tokens and these early cardboard tickets were not marked for date, so abuse of the transfer system by traveling on two separate dates was possible and growing more frequent. This abuse was curtailed in later era of operations around the turn of the Century. This is when dated paper ticket transfers began to be issued and mass produced for use on the intersecting lines (see paper transfers below). When the last models of streetcars made their entrance into the scene in the 1930's: the "PCC car" (or Presidents' Conference Committee Car), the conductor's position became superfluous and all revenue handling was done by the operator. The motorman / operator now had to make change, issue transfers, as well as whatever other duties that were inherent to operating the trolley / streetcar, including but not limited to: changing the direction of the trolley pole at the end of a run, moving manually operated track switches (with a pry bar) so as to change route to a branch line off a main trunk line, cleaning rubbish, flipping the seats to face the traveling direction if so required, tallying the fares, giving directions, etc. Actually operating the streetcar or trolley itself on tracks was pretty straightforward: start, slow and stop, with no steering obviously. |

|

![]()

|

|

|

![]()

Zone

Checks - The Oddball of the Fare Collection Methods

also

known as the "Pay Enter - Pay Leave" fare method

| within each Zone (intra-zone) | 10 cents |

| from Zone 1 to Zone 2 or Zone 2 to Zone 3 (inter-zone): | 20 cents |

| from Zone 1 to Zone 3 (inter-zone): | 30 cents |

| And

obviously, the system will work with even more zones, if necessary. Ultimately, the driver collected the appropriate base fare (intra-zone) from the passengers upon boarding and then again (inter-zone) based on their distance upon their disembarking pursuant to the Zone Check issued when they boarded. It sounds more complicated than it is, but in actuality, it really was not. Furthermore, it is essential to note that most of the private bus operators operating in Queens fielded fleets of buses (also known as coaches); that were built without mid-body exit doors, as commonly seen on Board of Transportation, NYCTA and MaBSTOA buses. For some of the Queens operators, one set of doors at the front by the driver was sufficient for both entrance and exit; as seen in the image at right of a coach for Steinway Omnibus built by Mack Trucks in 1939. However, some companies would operate both types of buses (with and without mid-body doors); with buses equipped with center doors assigned to routes within single zones of operations. |

|

![]()

![]()

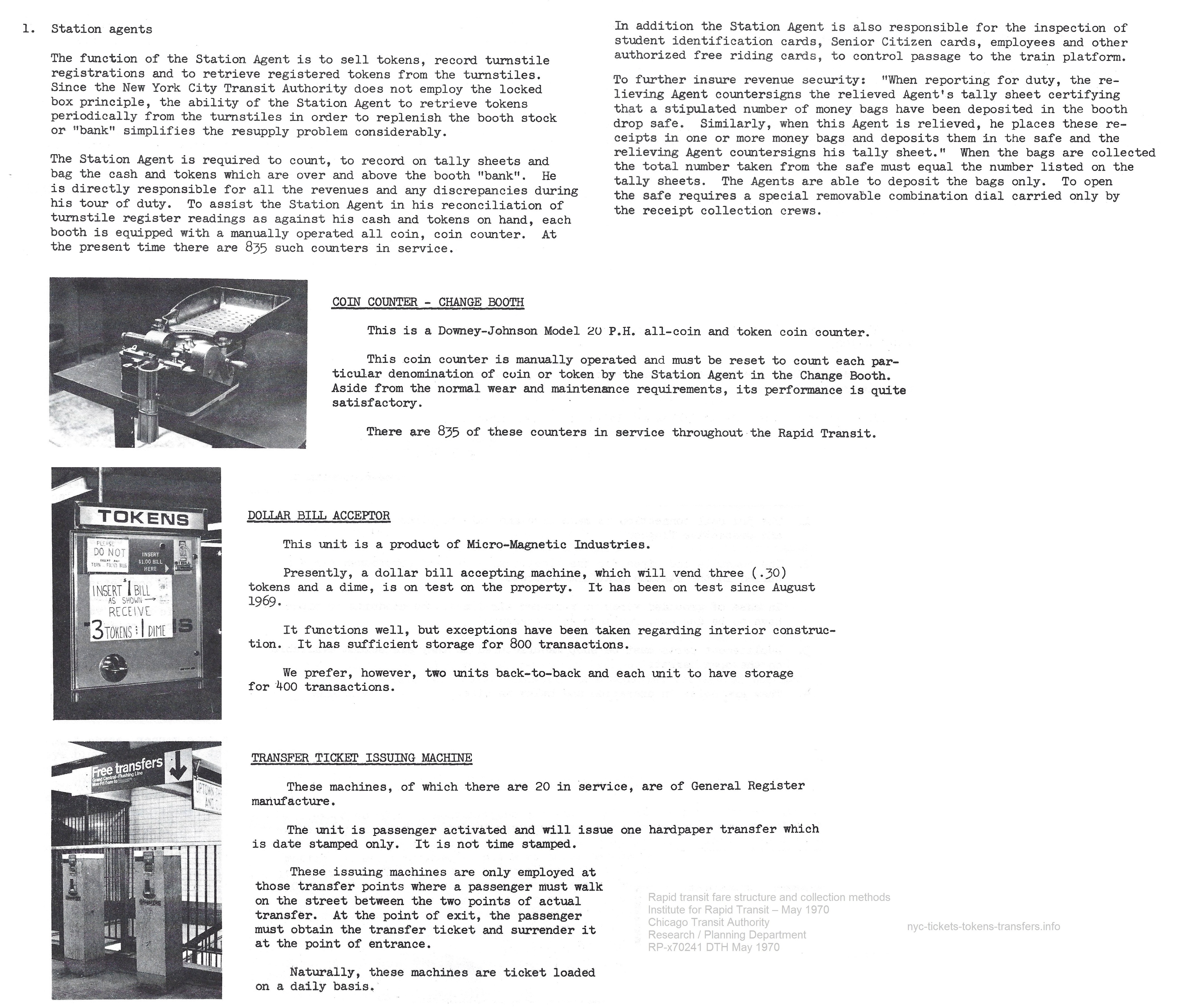

1) Railroad Clerks

colloquially known as "Token Clerks" or "Station Agents"

Beginning in 1880, Railroad Clerks sold tickets which were then handed to Gatemen with ticket choppers or to Conductors for collection. Beginning in 1922 and with the innovation of the mechanical turnstiles, the nickel was used to gain access. Railroad clerks exchanged dimes, quarters, half dollars and dollar coin and bills into nickels for the passenger; who then inserted a nickel into the turnstile.

2) Turnstiles

Or, if the passenger entered the system prepared with a nickel, the passenger could bypass the Railroad clerk, and proceed directly to the turnstile.

3) On Board Fare Collection

Between ca. 1945 and 1975; there was a singular exception to the turnstile payment method: The Conductor aboard the IRT Dyre Avenue Line (nights) collected fares onboard the subway car with a surface type farebox. A token or coinage was deposited, but no change was given.

Commencing in 1978 with the institution of JFK Express Service, this service employed the use of a Railroad Clerk on board each train to make change and sell tickets. This is because Railroad clerks were bonded and insured to handle money; and conductors were not. Therefore, the assignment of a Railroad Clerk on board each train was required.

4) Group collections;

Such as those for school field trips, tour groups, special events. Here a paper form was issued to the leader or administrator of said group, granting access to the transit system for a predetermined amount of people from a particular point of boarding to a point of disembarking. Many a school field trip to a museum or venue began or ended with the teacher handing over a form (usually on school stationery) to a Railroad Clerk at a subway station; then proceeding through the manual fare gates to the train platform. In most cases the fare was prepaid by the Board of Education or the group responsible for the excursion.

cover

. . |

page 1.

Description, Rates of Fare . |

page 2

Transfers, Reduced School Fare Transportation . |

page 3

Reduced School Fare Transportation (con't); Methods of Collection . |

Methods of Collection (con't): Station Agents, Turnstiles, Conductor on Train . |

page 5

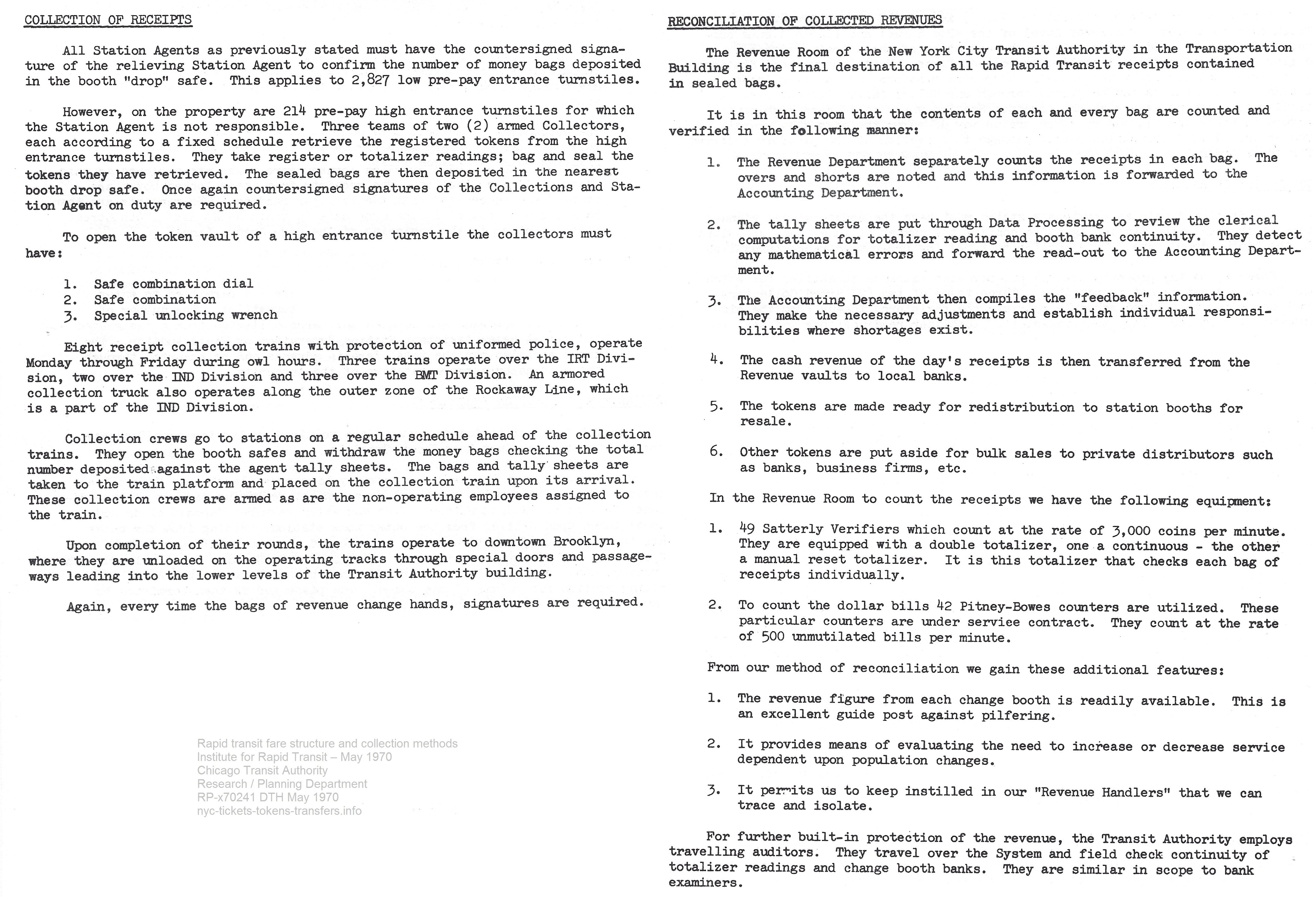

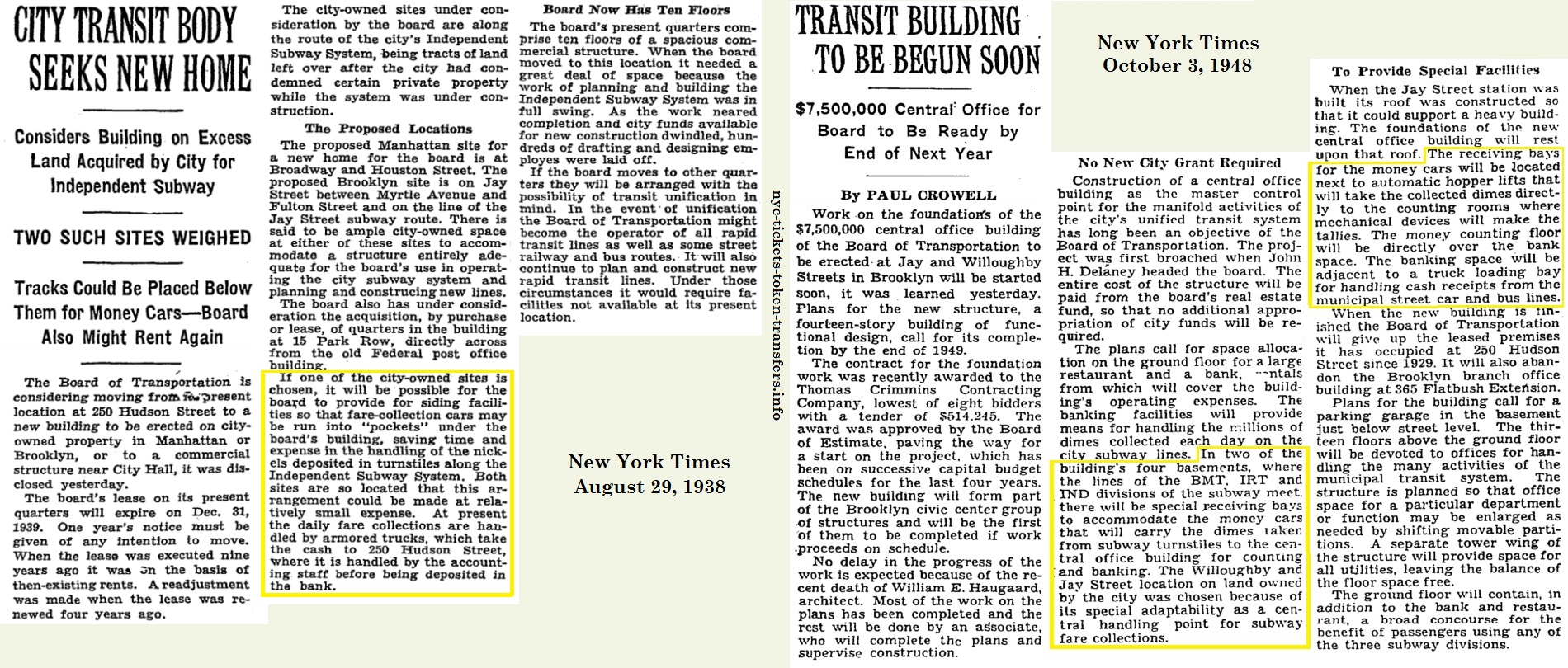

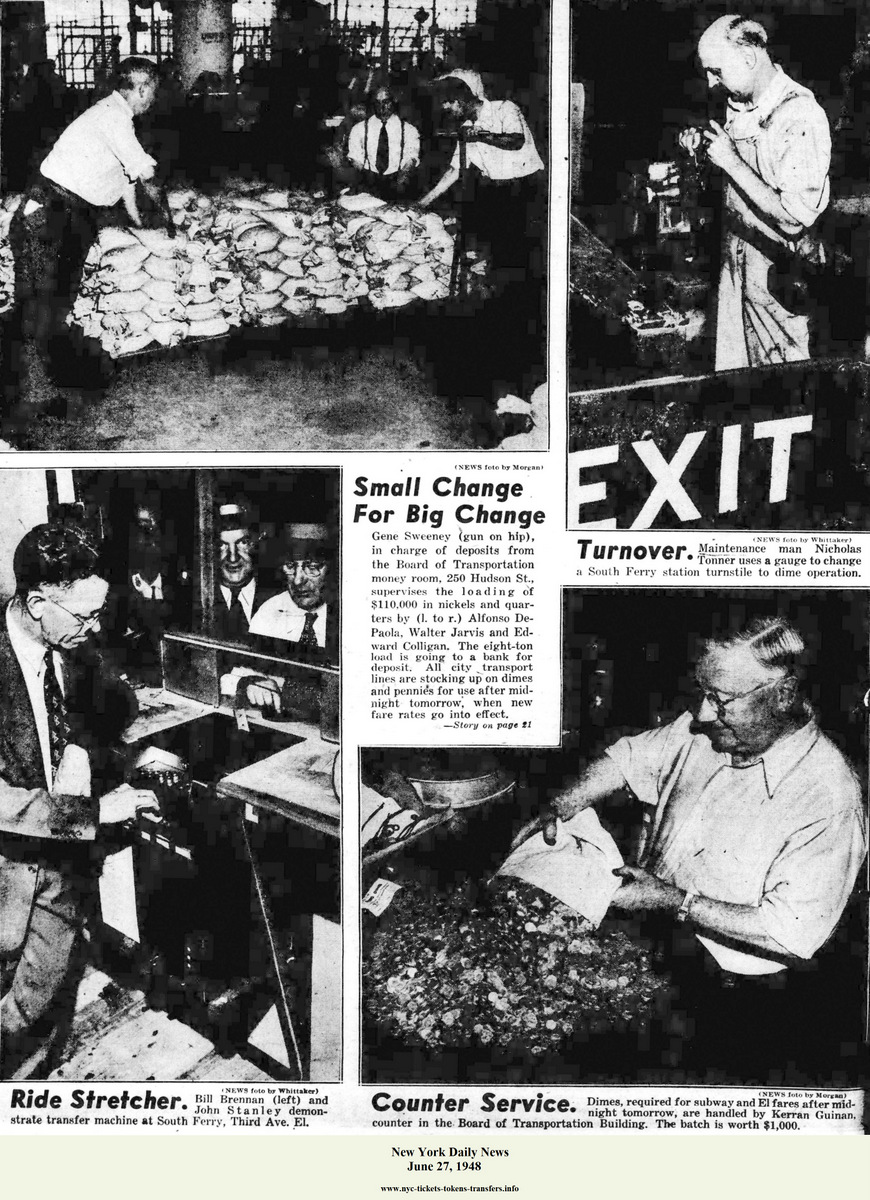

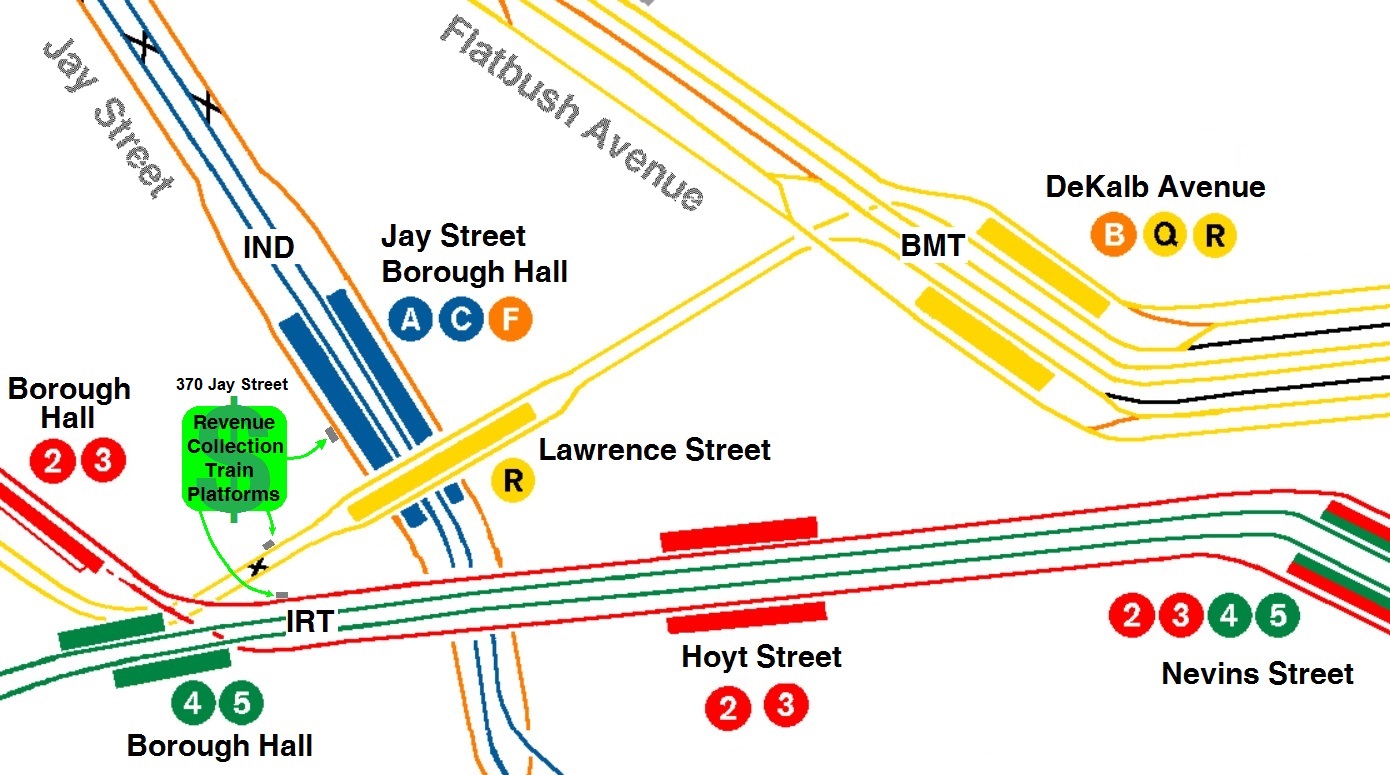

Special Fare Collection Procedures (Rockaway, Aqueduct), Collection of Receipts . |

page 6

Collection of Receipts (con't) Reconciliation of Collected Revenues . |

page 7

Reconciliation of Collected Revenues (con't) Fare Collection Research, Two Slot Coin Turnstiles . |

page 8

Fare Collection Research (con't) Type of Turnstiles and Allied Equipment . |

page 9

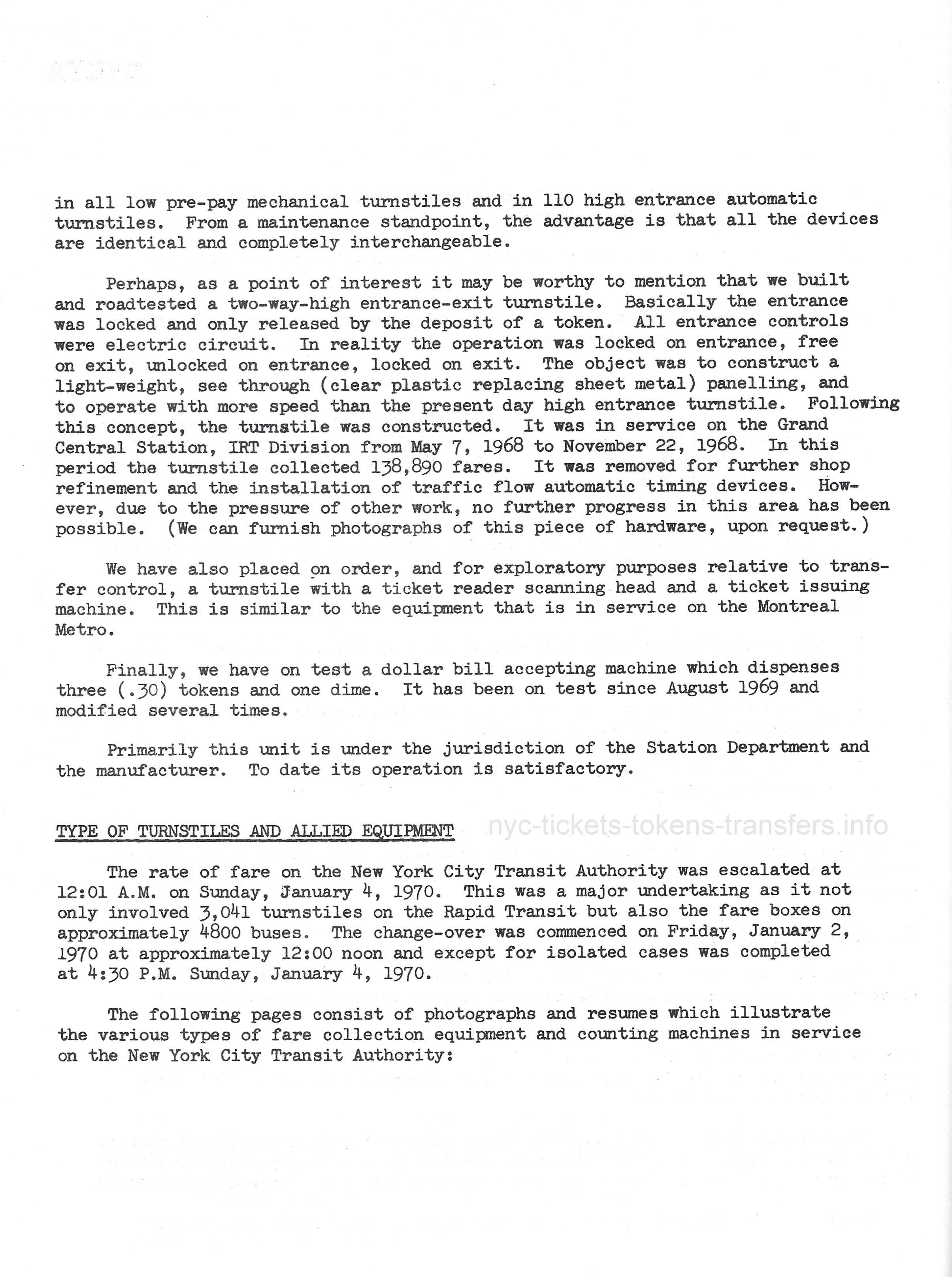

Coin Counter, Change Booth - Downey Johnson Model 20 P.H. Coin Counter, Revenue Room - Satterly Verifiers Model D . |

page 10

Bill Counter, Revenue Room - Pitney Bowes Tickometer Model #1700 Transfer Ticket Issuing Machine, General Register (small format card tickets) . |

page 11

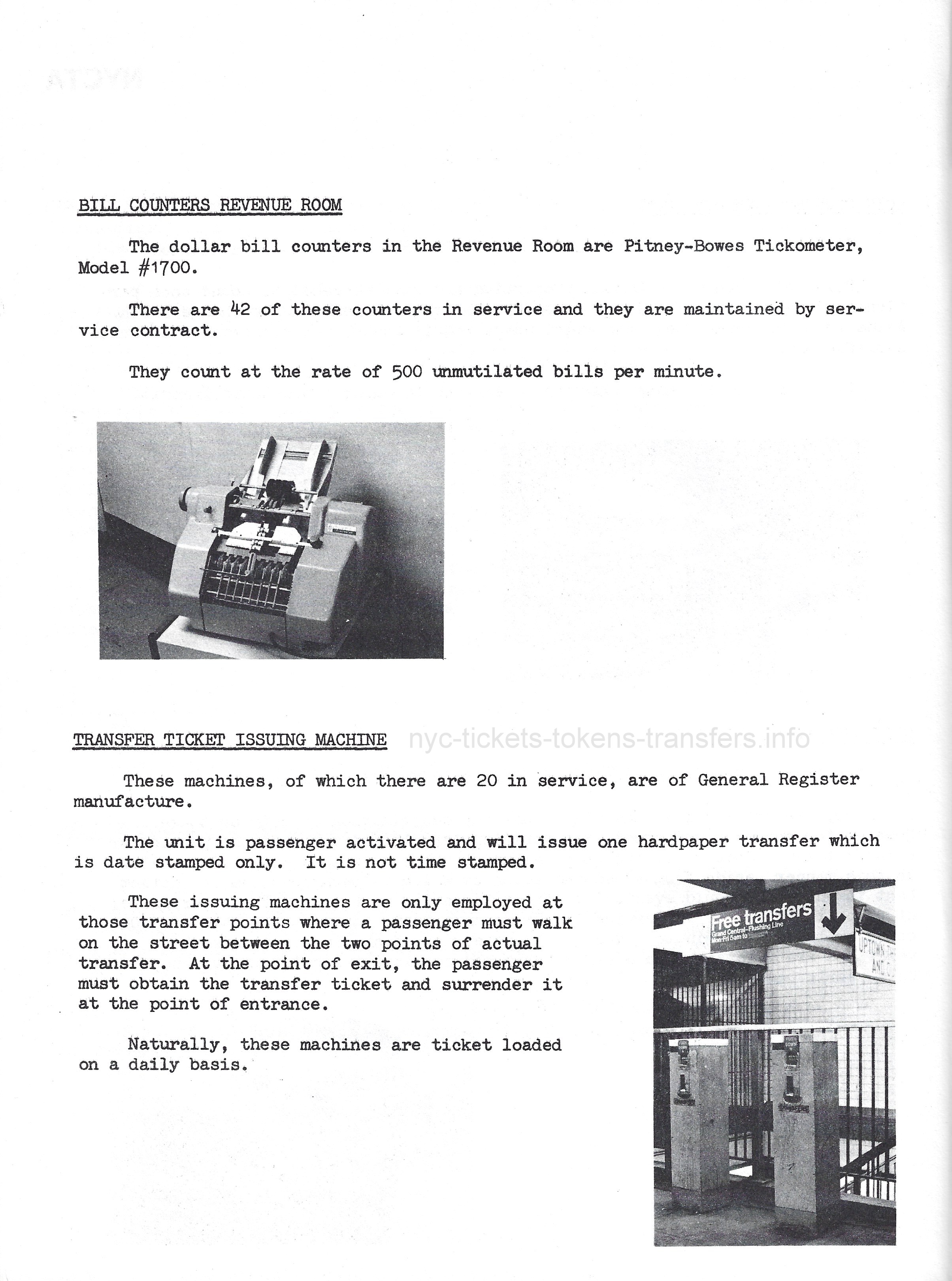

Johnson Fare Box D Type (Dyre Avenue Line nights) Dollar Bill Acceptor, Micro-Magnetic Industries (3 tokens & dime) . |

page 12

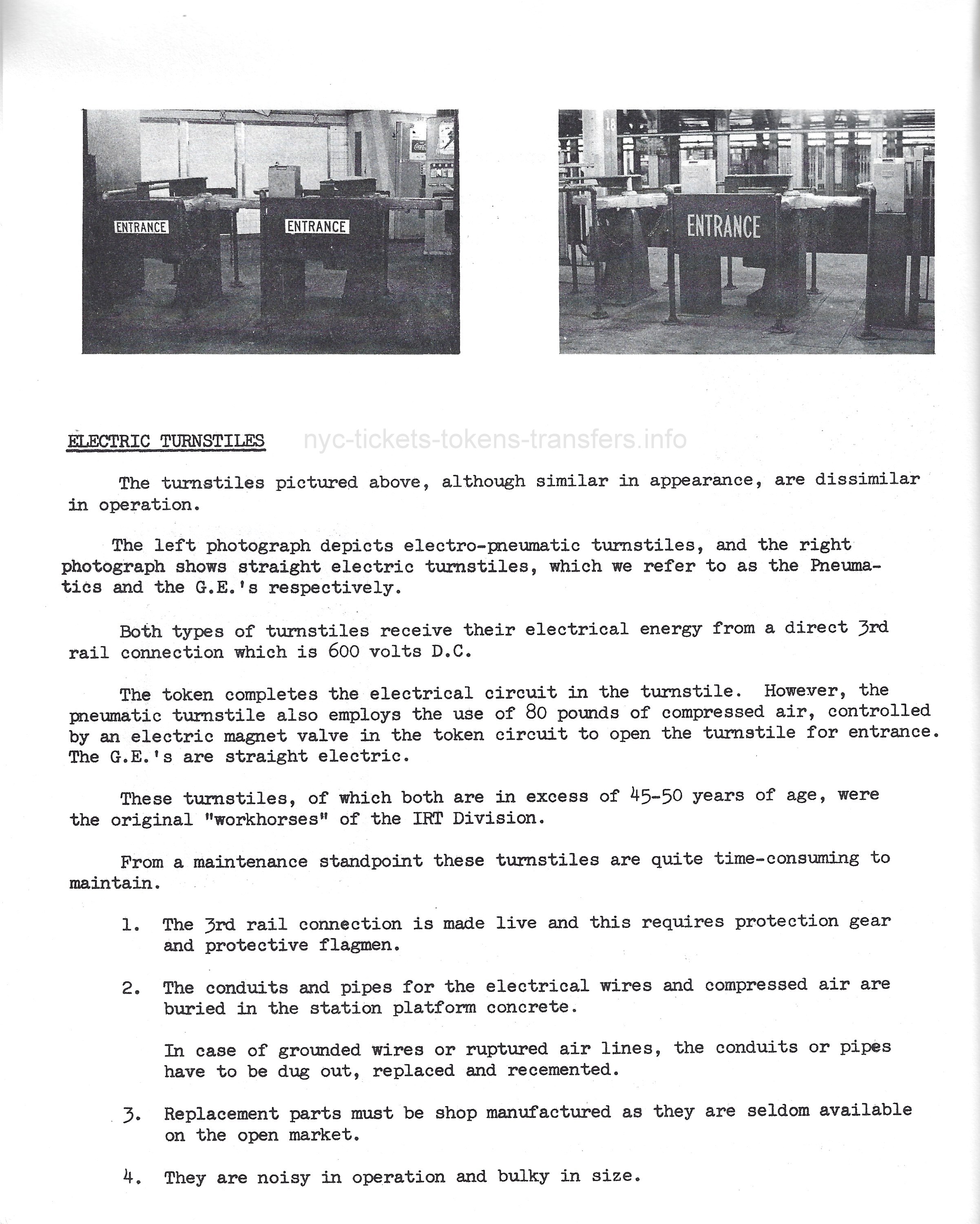

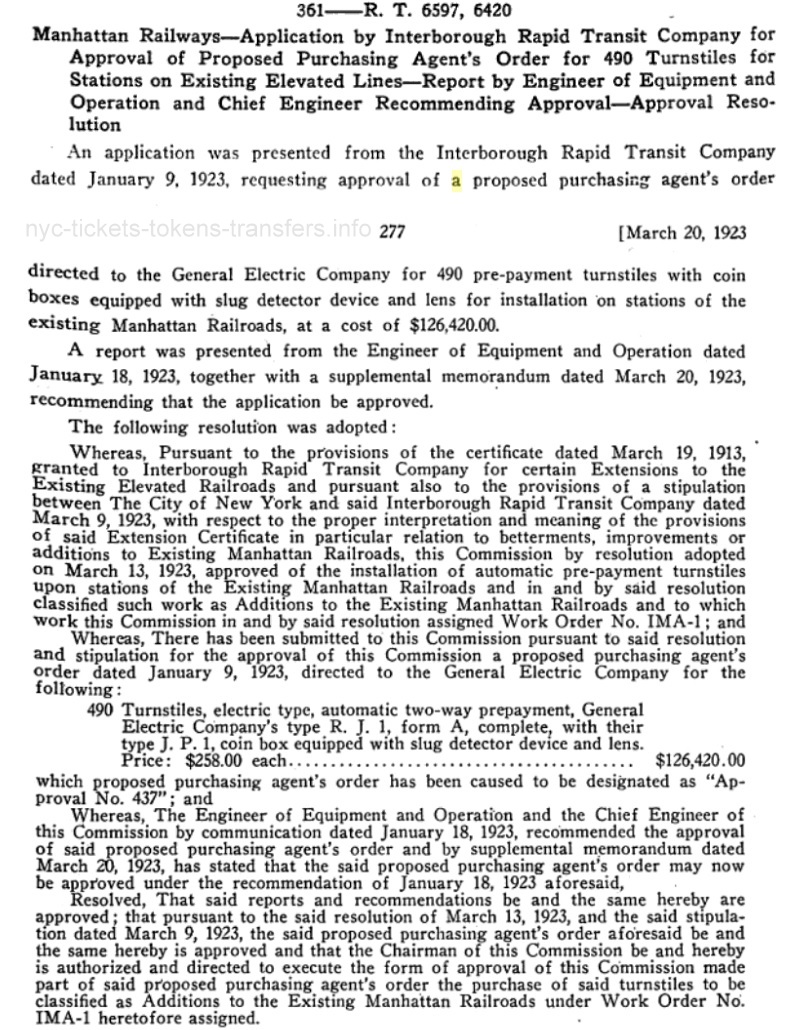

Electric Turnstiles, Electro-pneumatics & General Electric Straight Electrics (600 volts) . |

page 13

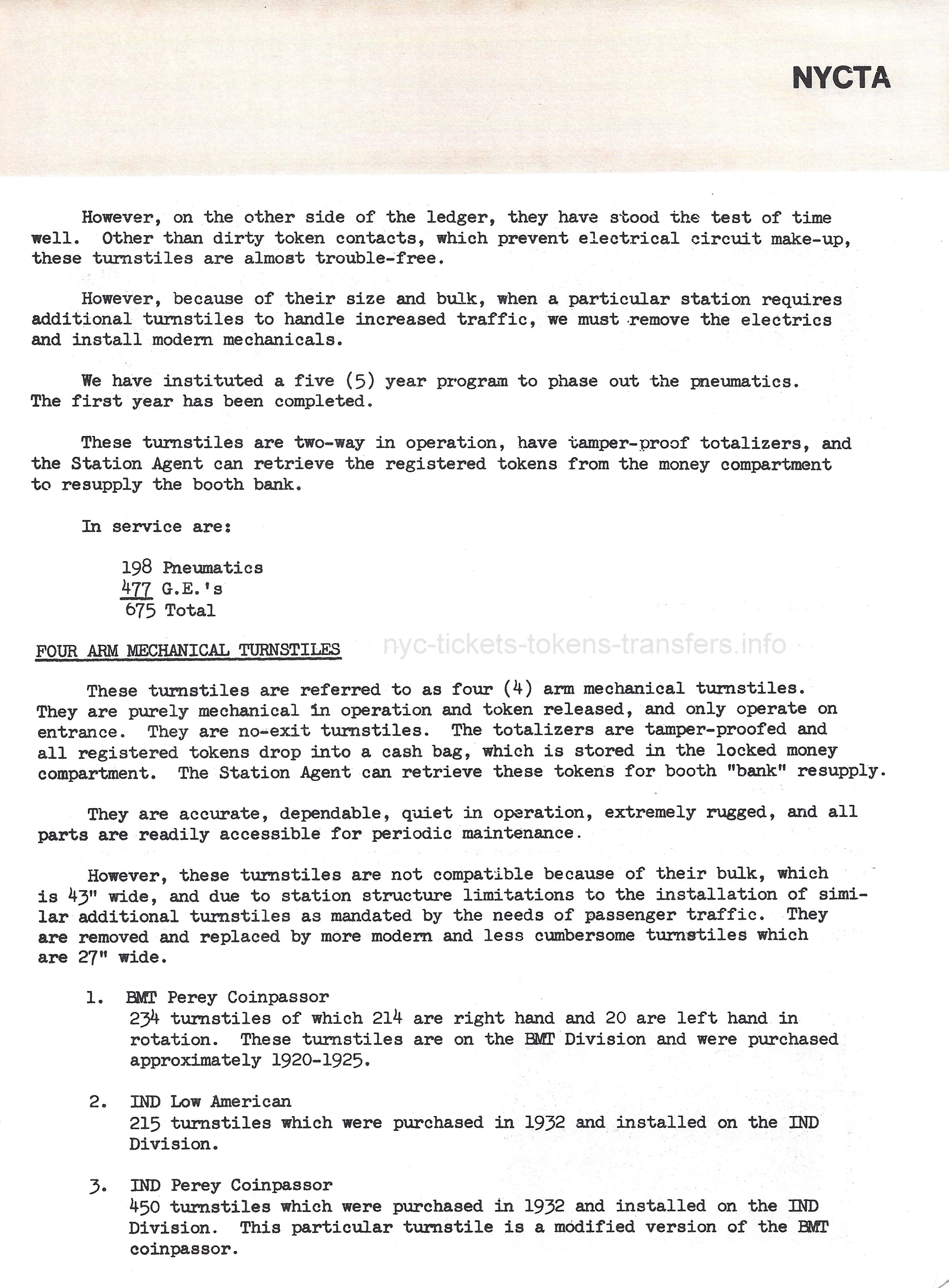

Electric Turnstiles, (con't) Mechanical Turnstiles, Four Arm: BMT Perey Coinpassor, IND Low American & IND Perey Coinpassor . |

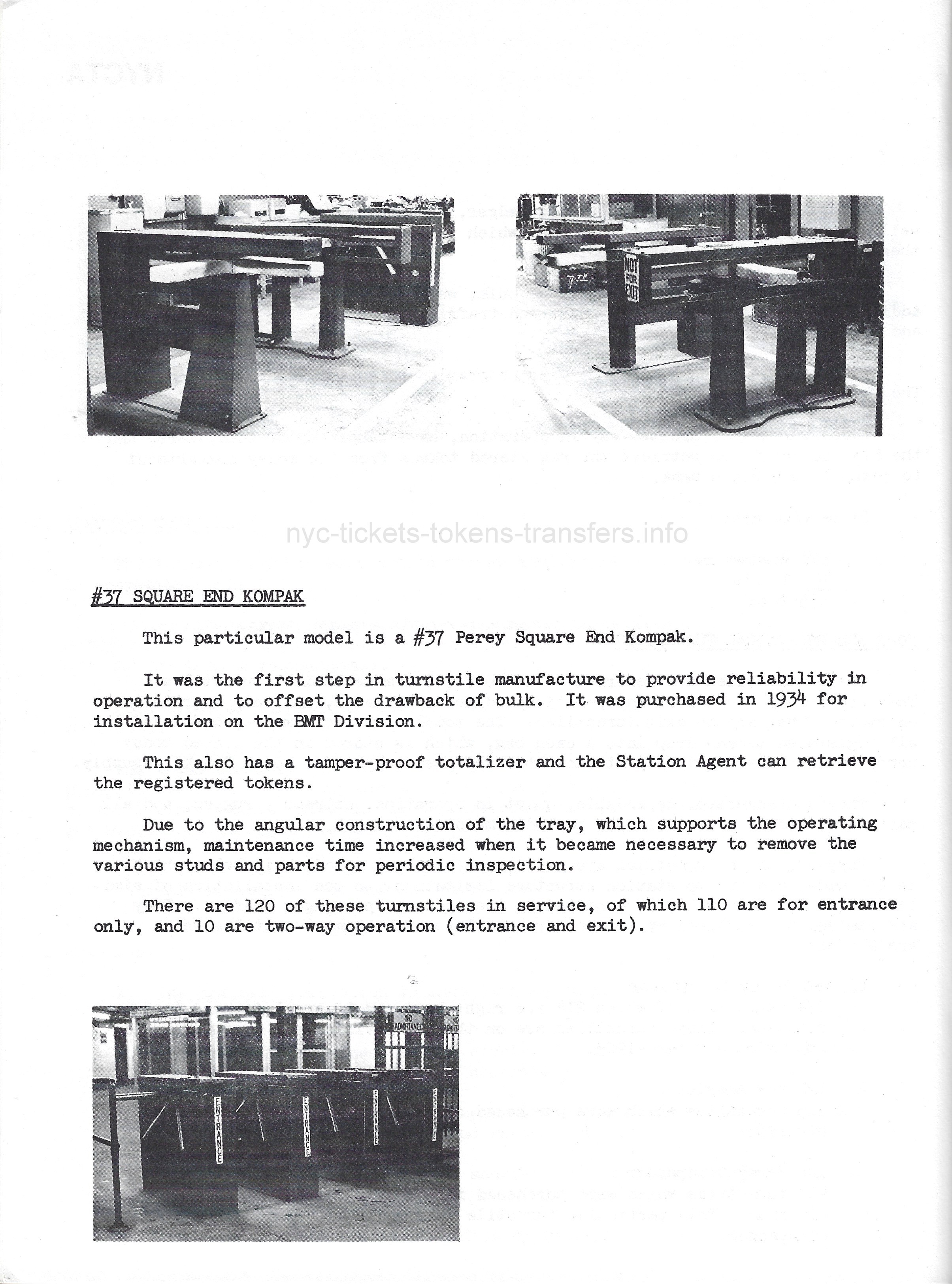

page 14

Perey #37 Square End Compak . |

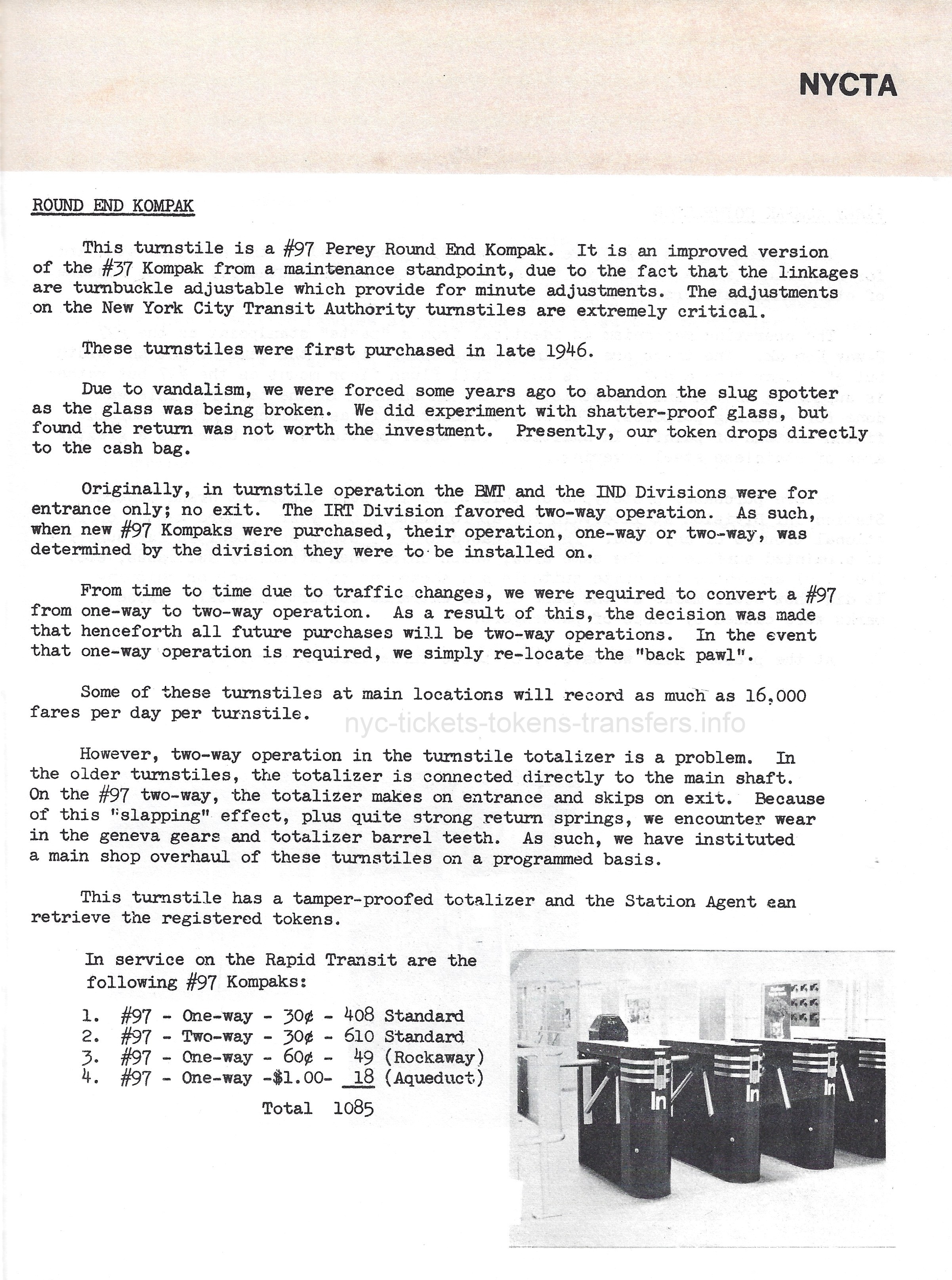

page 15

Perey #97 Round End Kompak . |

page 16

Perey #107 Kompak Coinpassor . |

page 17

High Entrance Exit Turnstiles . |

![]()

![]()

|

We see as a result of this article, the method of ticket

collection was changed from conductors taking up tickets aboard the

train, which was abolished on January 20, 1879. The reason for this was, at times of large crowds - especially during rush hours; the conductor may not have gotten to taking your ticket before you disembarked at your station; allowing you to ride for free and using your ticket on another date. So, the collection of tickets now required passengers to deposit their tickets into ticket boxes upon exiting the train at the exit gates. With this method, it also caused congestion when trains discharged the passengers in one short time span. And so, on June 21, 1880; the method of ticket collection would change yet again. Passengers now had to deposit their tickets into chopper boxes prior to boarding the trains; and it is this method of ticket collection that would gain widespread use for other rapid transit companies in the Cities of New York, the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens as well. This method worked the best, considering people arriving to purchase their tickets and hand them to the gateman were for the most part spread out over time. Granted, you can still get a crush of people, but the groups were smaller than on discharge of a train arriving in a station. After purchasing their ticket(s) a patron would proceed to the gate which divided the "open area" or public spaces from the "fare controlled area" which was the stairs that led to the subway or elevated platforms. Here, at an opening in this gate, a collector or "gateman" stood next to a glass and wood box on a pedestal, called a "chopper box". The passenger would hand the ticket to the gateman, who would place the ticket into the top of the "ticket chopper", and actuated the handle that in turn chopped the ticket, preventing reuse. This action finally granted you access to the "controlled area", also known as the platforms of the subway and elevateds, or main terminals of the surface cars. |

.

.

. .

.

Proceedings of the

American

Society of Civil Engineers, August 1917

|

|

|

| Columbus

Circle Station; showing change / ticket booth; and gate separating

"unpaid" area (and stairs to the street) and "paid" side (subway platform) areas. This image was taken upon completion of construction and the chopper box not yet installed. |

Gateman with chopper box. Note the second chopper box covered by canvas and not in use. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gateman with chopper box. image courtesy of New York Transit Museum |

Ticket Chopper Box at

IRT Wall Street

Station

image courtesy of ephemeralnewyork |

Deposit

slot, glass viewing box and "funnel" image courtesy of New York Transit Museum |

Chopping

mechanism (slightly damaged) and removed from wood cabinet. image courtesy of New York Transit Museum |

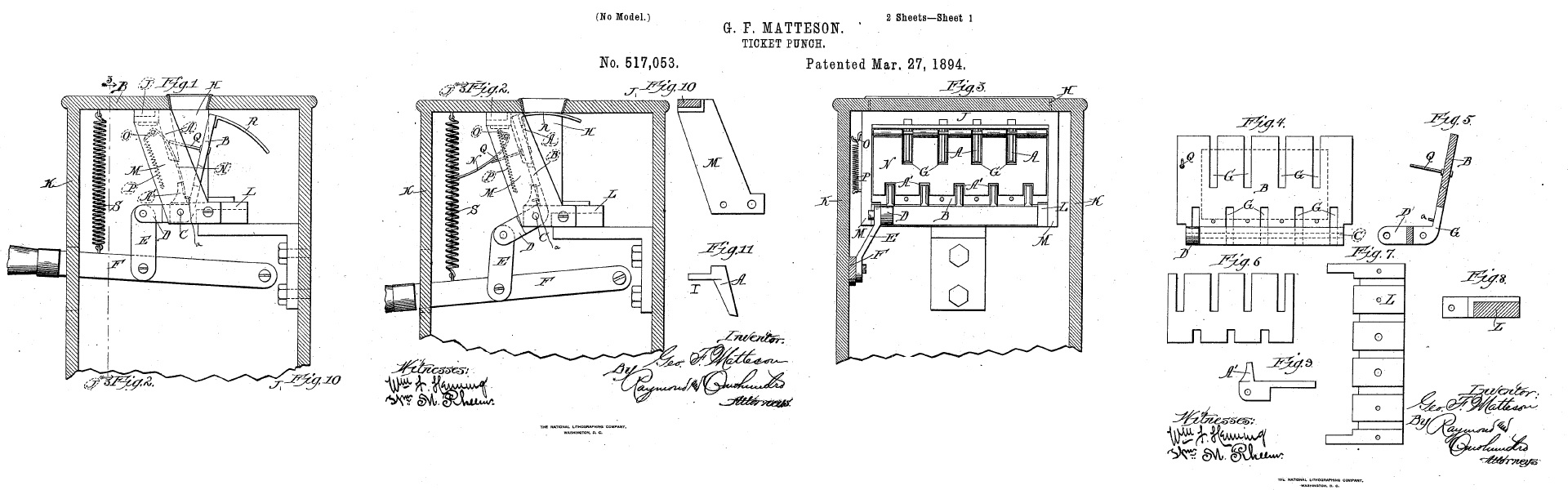

The glass box on top had a glass plate v-shaped funnel at the bottom (not shown in the patent drawings) which directed the tickets into the chopper box. Here a set of interlaced metal teeth resembling combs are mounted. Connecting to these teeth combs, there was a shaft that connected through the side of the case to the outside. Much like the purpose of a modern paper shredder; only the chopper boxes were manually operated. The tickets were chopped to prevent reuse and the shredded tickets contained in a hopper in the bottom portion of the chopper box pedestal.

|

|

| IRT Ninth Avenue Elevated 72nd Street and Columbus Avenue Station - February 6, 1936 Berenice Abbott photo "Changing New York" series |

IRT White Plains

Line Gun Hill Road Station,

ca. 1973 (just prior to the cessation of service on the Third Avenue Elevated - April 29, 1973.) unknown provenance |

|

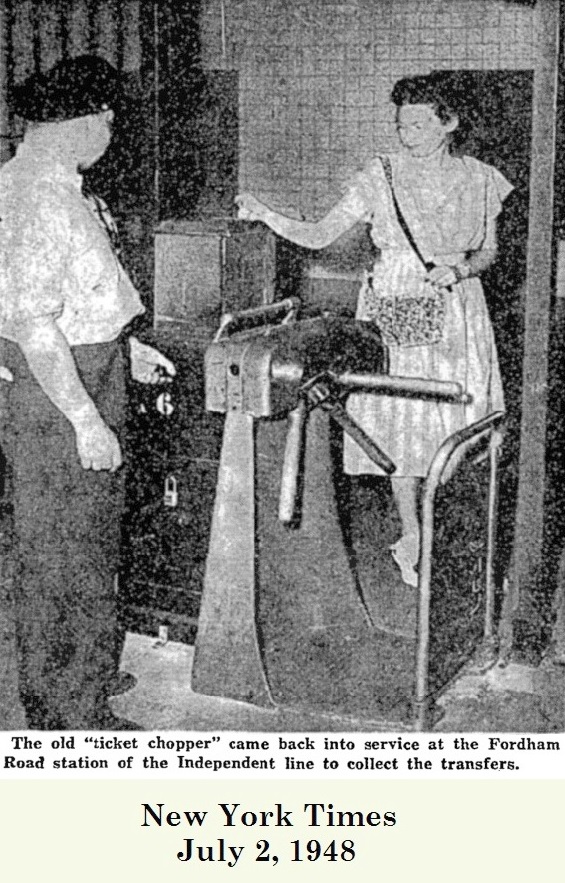

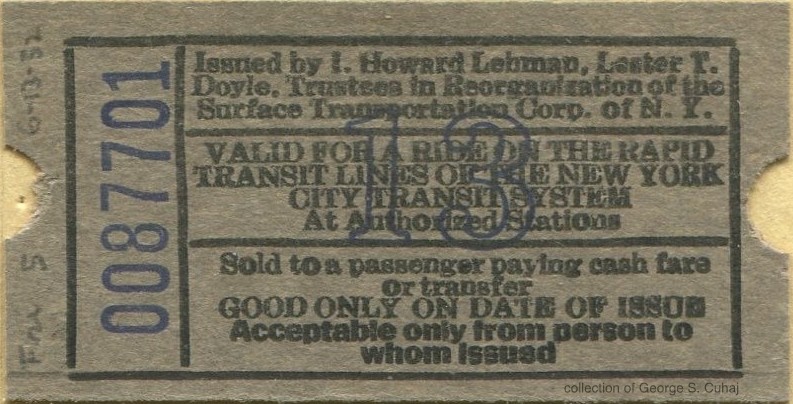

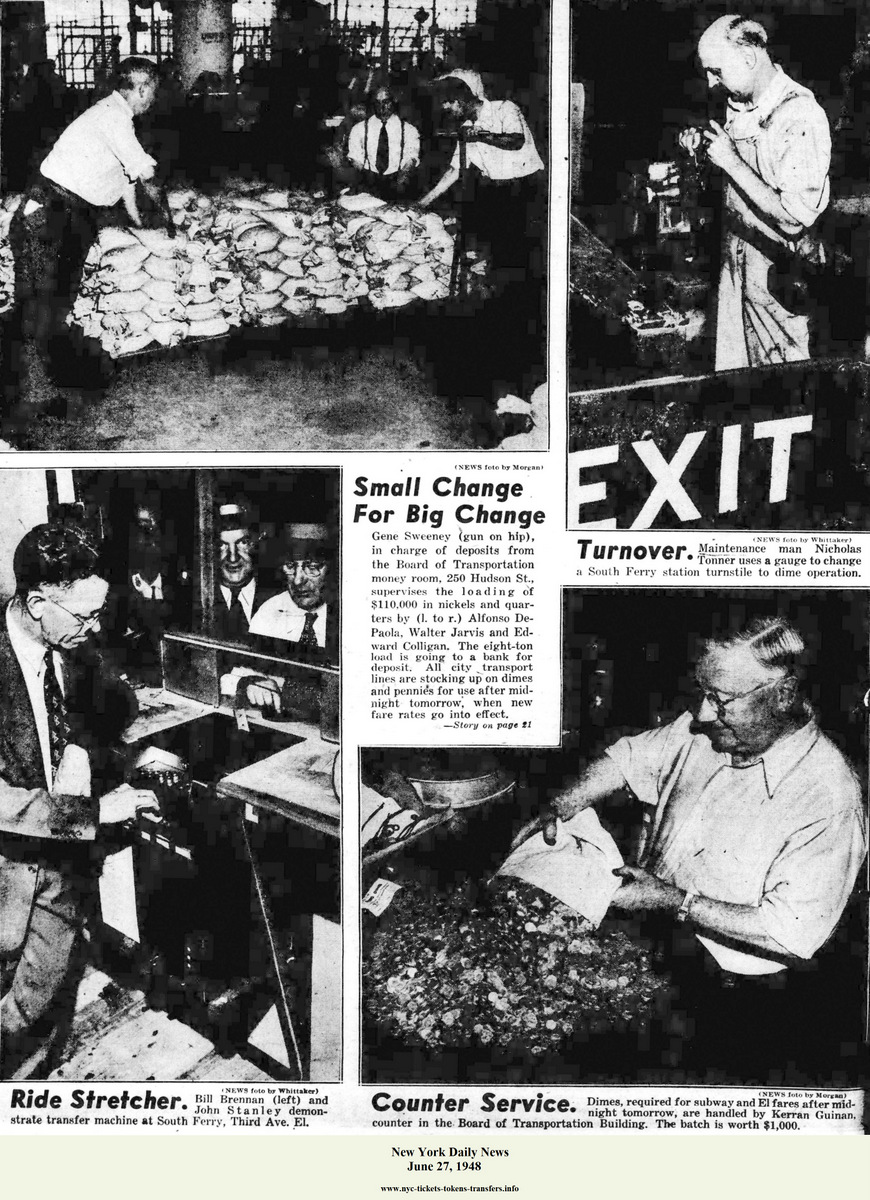

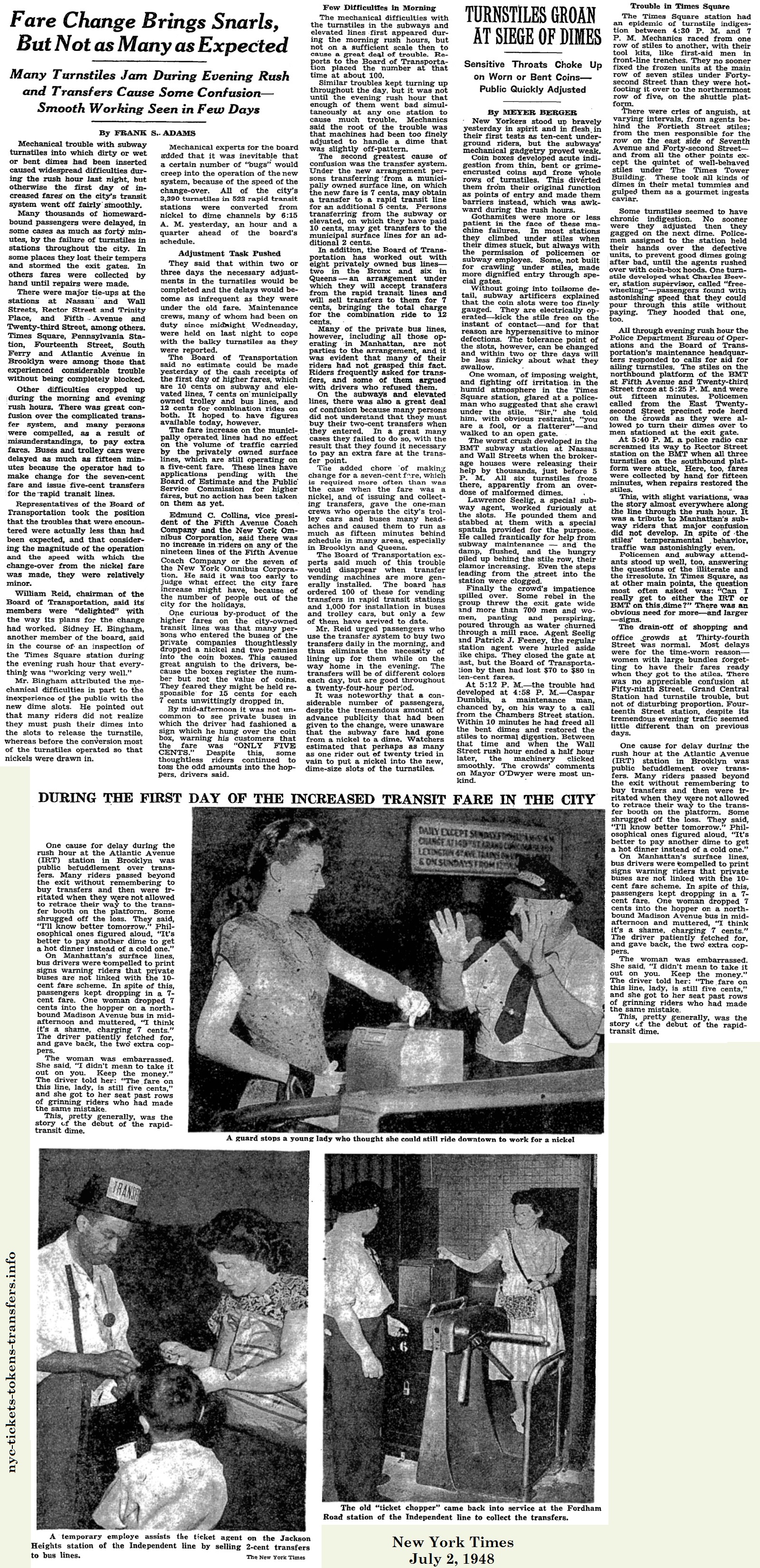

Recently discovered in the New York Times issue

dated July 2,

1948, and in the multi-page coverage regarding the fare raise to 10

cents the day before; is a photo of a Transit

Employee with a chopper box placed next to a portable turnstile (Perey

Model 48 "HD") accepting the new

small format combination (surface to rapid) tickets at the Fordham Road

Station in the Bronx! The caption reads, "The old ticket chopper" came back into service at the Fordham Road Station of the Independent Line to collect the transfers." It is also interesting to note that the model turnstile shown next to the chopper box, is a model used in surface transit applications: streetcars and buses. It appears here it is being used as a counting mechanism. Returning to the image; the intersecting surface lines for the Fordham Station would have been the Surface Transportation Corp. Bx12 and Bx19 routes, and the ticket being deposited would have been almost identical to the one shown at below left. Friday July 2, would have been gray ticket like shown, but with a number "2". Anecdotal recollection of a member in the Facebook group for the Transit Museum recalls a chopper box being used in the 1960's to collect the inter-divisional continuing ride transfers from the Fulton IND Line in the BMT Franklin Avenue Shuttle station. Chopper boxes were even used as late as June 30, 1980 albeit as a simple receptacle to help accept old tokens and a dime for the June 28, 1980 fare hike (and new token release), as seen in the New York Times article at right. |

|

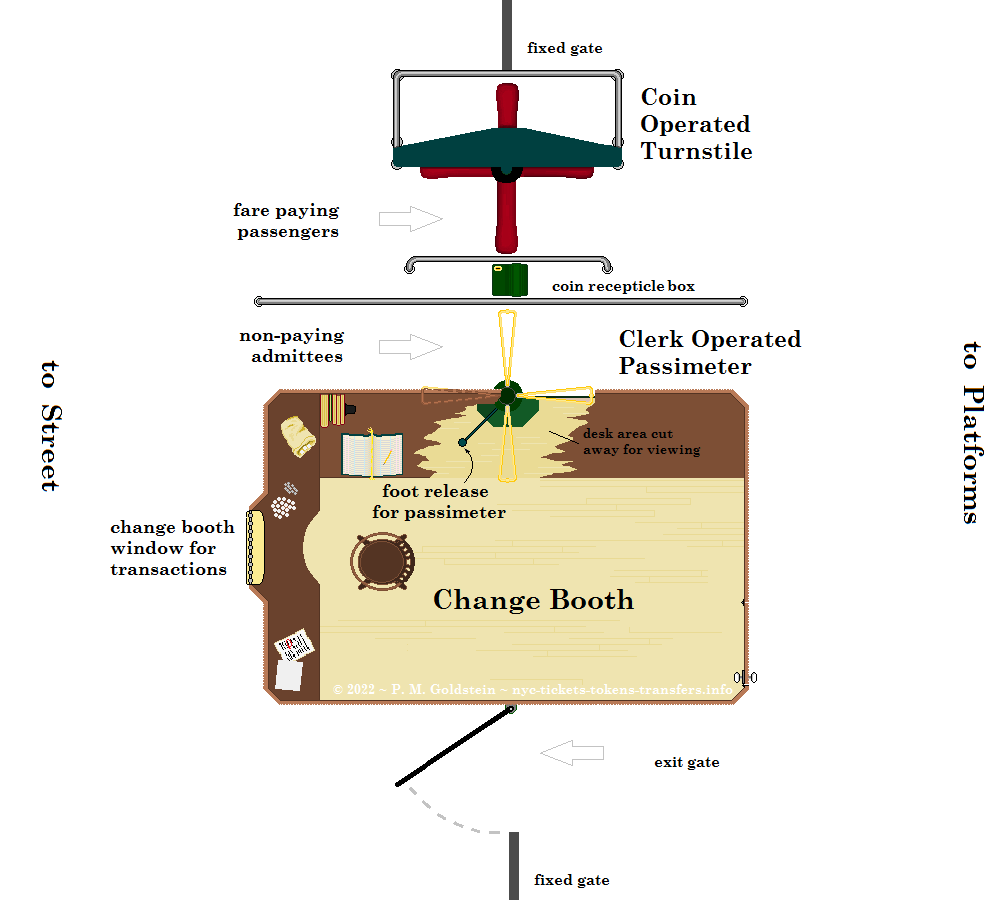

![]()

| Manually operated booth-side Passimeter | |

|

These types of turnstiles were manually activated by the

change

clerk inside the booth. They were not automatic and there was no coin

operated mechanism

to release them. The passimeter was mounted halfway through the side wall of the change booth, with a gate and turnstile arm projecting outside the wall of the change booth, and with the side with the foot lever and counter projected into the booth. Usually a shelf covered the arm inside the booth so the clerk was protected from walking into it and had more work area. When a passenger who was entitled to travel for free, the change clerk would depress the foot lever which in turn released the arms, allowing the person to now pass through to the revenue side of the station. This happened more than people realize: it could be another transit employee, a policeman, a student, a vending machine owner filling up the Chicklets / Beeman's dispenser, or perhaps an advertising man changing the posters from Burma Shave to Barbasol. Coin operated turnstiles were mounted to the outside of the passimeter lane. In the earliest days of fare revenue collection, the terminology in the trade journals was specific: these were passimeters. Automatic coin operated versions were known as turnstiles. As time progressed, the passimeters were lumped into the turnstile category; and as passimeter gave way to the "electric lock gate", so as the passimeters faded from use; terminology was no longer an issue. |

|

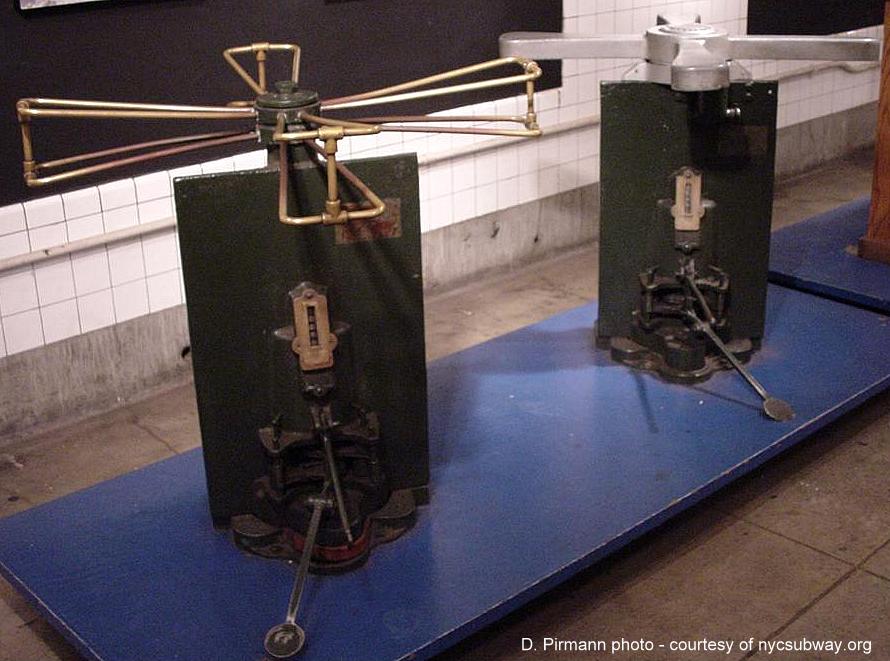

left unit:

IRT; right unit: BRT / BMT  |

|

designed by IRT;

manufactured by General Electric: the "Featherweight

Pressure Gate" - 1921

|

|||||||

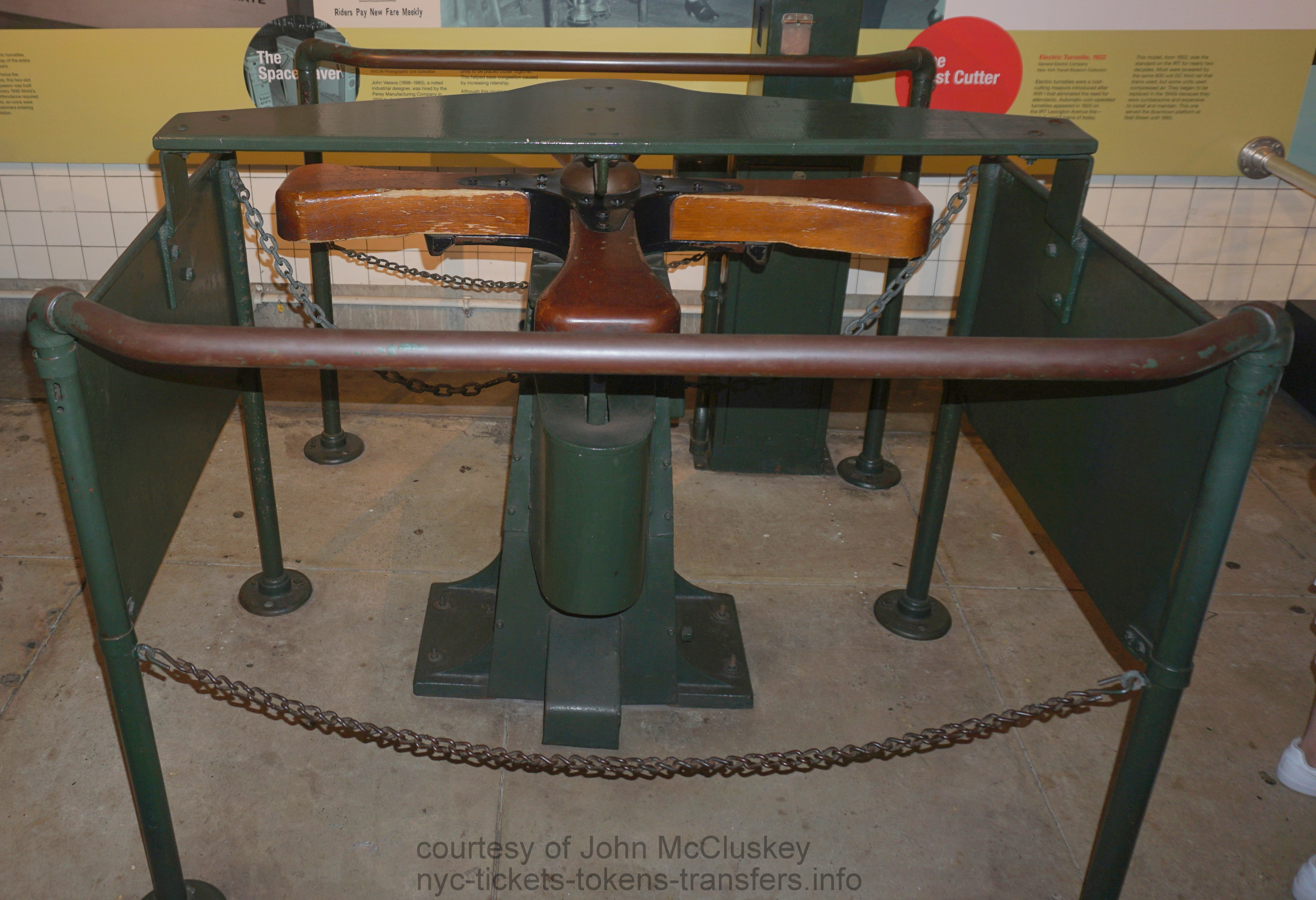

| The first electro-mechanical / electro-pneumatic turnstile for the New York City subways and elevateds was not deployed until June 1921, and after being filed for a patent that same year, by Mssrs. Frank S. Hedley of Yonkers and James S. Doyle of Mount Vernon, NY. If these names happen to sound vaguely familiar, perhaps that is because Frank S. Hedley was the President and General Manager, and James S. Doyle was Superintendent for the Mechanical Department, of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company. They were revolutionary for their time and even had a name: "Featherweight Pressure Gate" Other turnstiles mechanism were developed prior to this model, and required some serious pushing to get it to cycle. But this model was design specifically for high traffic rapid transit use, and it easy of turning made it well suited to the crush of thousands of passengers per hour. After the patent was granted and the demonstrator model successfully tried out in service, General Electric Company was contracted to manufacture them. It took until 1928 to install at least one of these turnstiles in each and every station on the IRT. There are images in the NYTM archives showing this model in service in the the 1950's!  uncovered hub type better image requested |

|

||||||

GE "Featherweight Pressure Gate" turnstile - entrance covered hub type there was a covered platform connecting the coin deposit and the turnstile mechanism, that is not included in the Transit Museum display. |

GE "Featherweight Pressure Gate" turnstile - side view covered hub type |

||||||

builders plate for GE "Featherweight Pressure Gate" turnstile |

|||||||

A little internet research located the following two entries which reveal that the Interborough Rapid Transit, and its subsidiary Manhattan Railway; were still in the process of purchasing turnstiles in January 1923! So, in short these documents confirm, and refute the New York Transit Museum's erroneous statements that the ticket choppers were replaced in 1921, as IRT / Manhattan Rwys were still purchasing turnstiles to replace the choppers. These documents also enlighten us to the cost of the turnstile: $258.00 per unit |

|||||||

both: Proceedings of the Transit Commission, State of New York, Volume 3 January 1, to December 31, 1923 |

|

||||||

| fare media: | nickel | 1921 - 1948 |

| dime | 1948 - 1953 | |

| tokens | 1953 - |

|

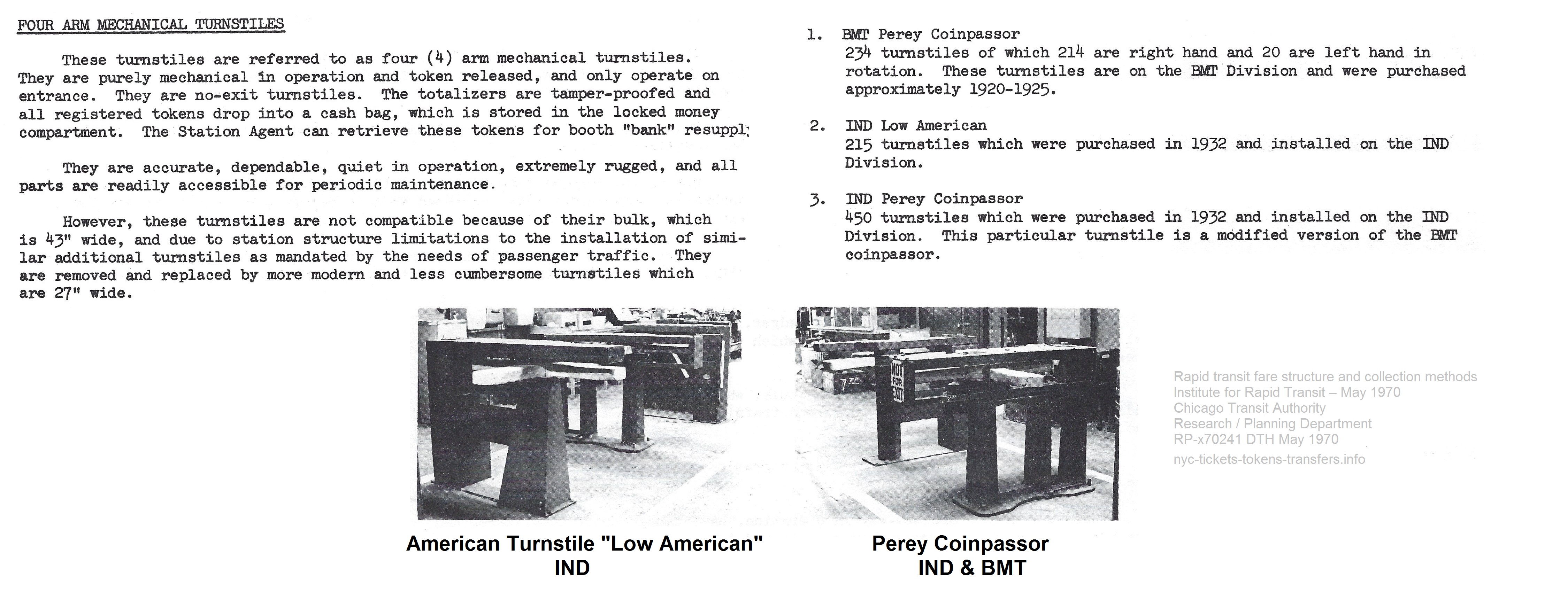

Manufactured by Perey, Model #55 "Coinpassor". This type of turnstile; was first introduced in 1920 and this

model

was strictly mechanical, and would accept nickels, dimes and when introduced in 1953, tokens. The only online reference I can find regarding this model, is the 1970 "Rapid Transit Fare Structure and Collection Methods" published by the Institute for Rapid Transit (U.S.). In this reference it's referred to as the "BMT Perey Coinpassor":  1970 "Rapid Transit Fare Structure and Collection Methods" published by the Institute for Rapid Transit (U.S.) This now leads me to believe the IRT, the BMT and the IND all used different turnstiles. This would make sense as each was its own organization prior to unification in 1940, and only after would turnstile use be universal. Another interesting facet about the above entry, is that 20 were left hand rotation. One has to wonder what locations these were required for. Research is needed to ascertain if this model was in fact used on IRT lines as well. According to the image at right, this is an IND installation; so we are now aware the Perey 55 Coinpassors were installed at IND stations as well. As such, it appears this turnstile replaced the Low American four paddle turnstiles. Also, it is understood this model is not on display at the Transit Museum. The Coinpassors were designed to be bolted directly to concrete, and incorporated a rub rail for an adjoining turnstile lane. Note that the "Coinpassor" 55 is a cousin to the "Superstyle" 55 seen below. The Superstyle had a non-slip diamond plate / pattern plate base and a side railing for easy installation and removal in streetcars and buses. |

Turnstiles on IND, ca. 1970 New York Transit Museum archives. |

Perey Model "HD" 48 and

"Superstyle" 55 - circa 1930's

|

|||||||

This model of turnstile was not used for rapid transit (subway / elevated) fare collection, but it was used by the surface transportation vehicles beginning around 1930; namely the newer model streetcars (Presidential Conference Committee Cars) and even some internal combustion powered bus models of that era as well.

These models of turnstiles were utilized with both nickels and the "transfer tokens" issued by the surface operators in the 1930's and 1940's: Brooklyn Bus Corporation, Brooklyn & Queens Transit, Board of Transportation - Transit System - Brooklyn Manhattan Transit Division, etc. |

Perey Model

55 "Superstyle"

|

||||||

|

In this area of

operation, the surface transfer system had a lot of variations. There

were transfers that cost 2 cents, and some were free and some companies

charged 3 cents for the transfer. Normally, with a fare box equipped

vehicle; a

passenger handed their paper transfer to the operator / driver and the

passenger proceeded to the rear

of the streetcar / bus to find a seat. The installation of this turnstile hindered that operation. As the turnstile was mounted in the aisle a few feet behind the driver and the passenger now had to pass through it to reach the seating portion of the vehicle - it was accessible only by the passenger. The passenger now needed some form of fare media to activate the turnstile to be able to pass through. Since the transfer had already been prepaid; depositing additional funds was not the answer as that would incur a double payment upon the passenger. The solution laid with the use of transfer tokens to overcome that turnstile obstacle. When a passenger desired a transfer to another line, it was requested at time of boarding of the first streetcar / bus. The two cent surcharge was paid directly to the operator on the first streetcar or bus, or if it was free; presented the passenger with the applicable paper transfer. When that passenger boarded the second streetcar or bus, they surrendered the paper transfer to the operator; and in turn the operator gave the passenger a transfer token to be deposited into the turnstile, permitting the passenger to proceed through to the back of the streetcar / bus. In no other terms, it was an added labor procedure that accomplished the same end result. In the case of free transfers, a token was issued just as well to pass through the turnstile; however, it appears very likely that the two different color tokens were used to denote the different fare structure: one for free transfers and the other for 2 cent transfers. Perhaps at some point, if the companies were steadfastly adamant about retaining the use of the turnstiles and not fareboxes; an electric release for the turnstile operated via push button by the operator would have sufficed, eliminating the need for the transfer tokens. Despite the initial outlay of producing the token issues, and the labor incurred in handling them; it was the fact that the turnstile took up too much space - its placement in the aisle between the first set of seats; was the ultimate factor against its continued use. Double seats now had to be replaced with single seats, and the seating capacity was reduced by at least four passengers. Or, during rush hour; thirty standing passengers packed in like sardines (just kidding!) - more like maybe ten standees. In either case, it reduced the carrying capacity of fare paying passengers. Detrimentally its position, in cases of short and sudden stops; standees would bang into it and / or even fall over it. More over, in a situation where passengers needed to get off the bus via the front doors, in case of emergency or when the rear exit doors were blocked by a crowd, the turnstile hindered this exit route. So, fareboxes remained king of revenue collections on the surface transit vehicles. Note that the "Superstyle" 55 seen above is a cousin to the "Coinpassor" 55, in the preceding chapter. The Superstyle had a non-slip diamond plate / pattern plate base and a side railing for easy installation and removal in streetcars and buses; whereas the Coinpassors were designed to be bolted directly to concrete, and incorporated a rub rail for an adjoining turnstile lane. |

|||||||

| fare media: | nickel | 1921 - 1948 |

| dime | 1948 - 1953 | |

| token | 1953 - post 1970 |

|

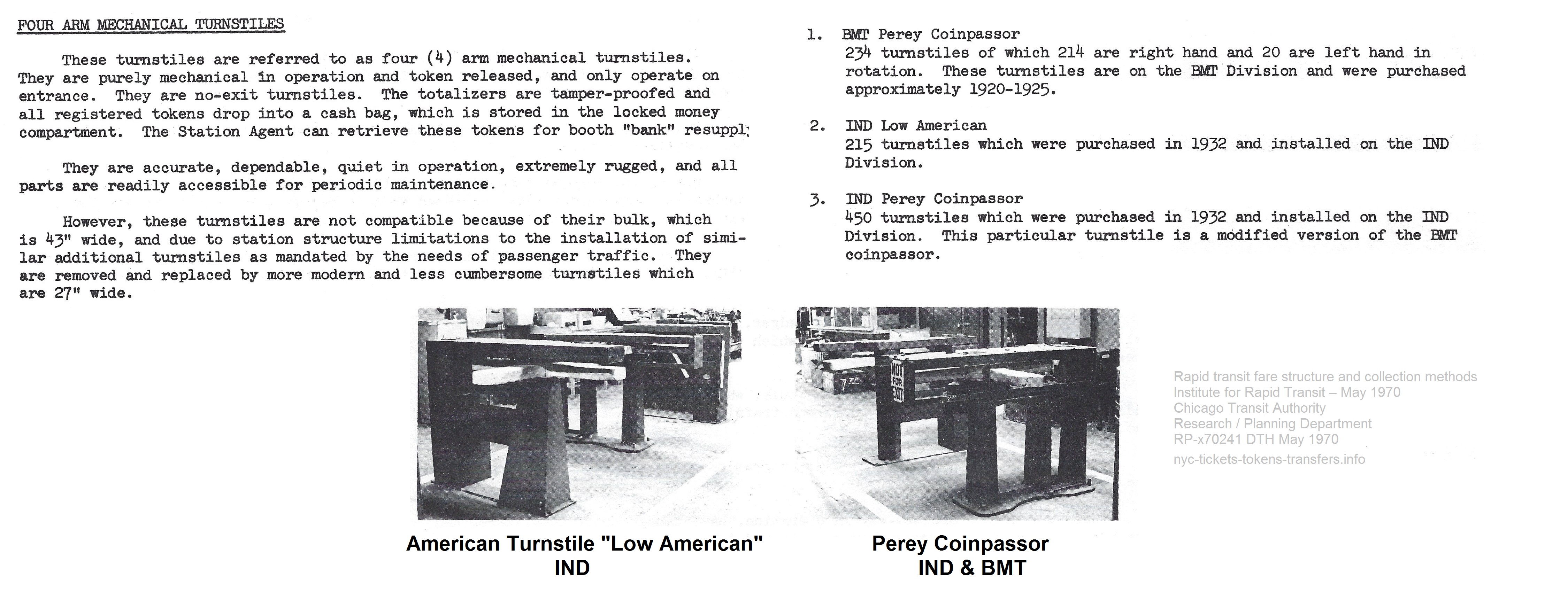

Manufactured by American Turnstile, model "Low American". This type of turnstile; was first introduced in 1932, with 215 purchased. In this following reference this particular turnstile is referred to as the "IND Low American"; which infers it was used on the IND (Board of Transportation) lines. This reference also lists the Perey Coinpassor as being the "BMT Perey Coinpassor." With this publication, this now leads us to understand that the IRT, the BMT and the IND divisions all used different turnstiles. This would make sense as each was its own organization prior to unification in 1940, and only after the second unification would turnstile model ordering be universal for any division. |

|

| fare media: | nickel | 1920 - 1948 |

| dime | 1948 - 1953 | |

| token | 1953 - post 1970 |

| Manufactured by Perey; Model Coinpassor A cursory glance comparing the IND Low American and the BMT / IND Coinpassors appear similar; but there are design differences. The Perey Coinpassor has three vertical legs and a sub-structure that protected the bottom of the arm mechanism whereas the Low American only had two legs with a horizontal plate connecting the two legs, with no protection for the arm mechanism. According to "Rapid Transit Fare Structure and Collection Methods" (Institute for Rapid Transit, May 1970): BMT version: 234 total units: 214 right hand, and 20 left hand operation (where used?) purchased 1920 through 1925. IND version: 450 purchased in 1932  |

|

Perey World's Fair Model - Double Fare - 1939 - 1940

|

|||||||

|

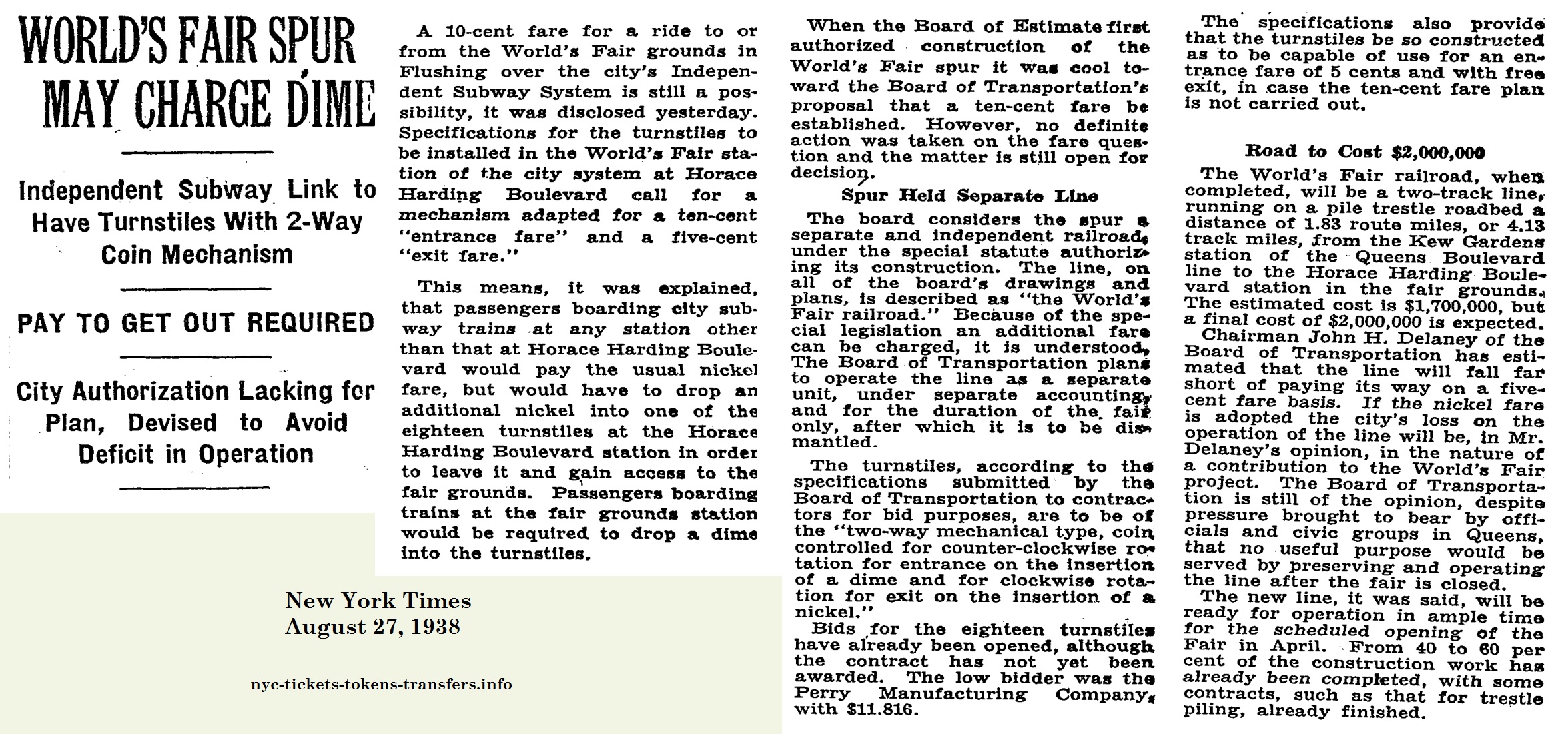

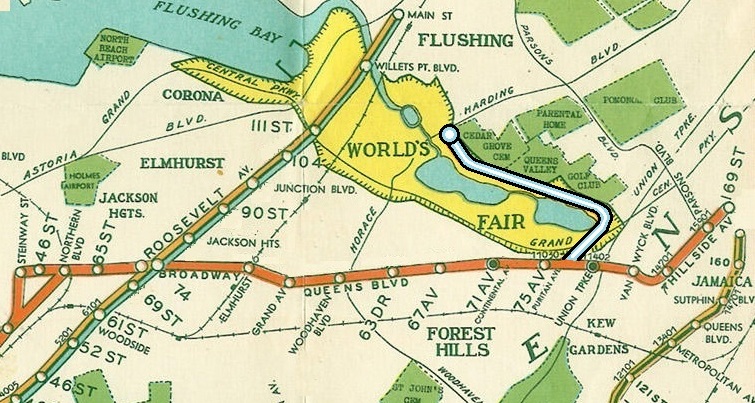

Manufactured by Perey, (model number not known at

this time). This

type of turnstile; was used for double fare

applications,

specifically at the 1939-1940 World's Fair at Corona - Flushing Meadows

Park. Double fares were collected at the World's Fair Station of 1939 - 1940 for passengers arriving to visit the location. An extra 5 cents was payable upon exit from the station, making the total fare paid 10 cents. Departing the World's Fair Station charged 10 cents upon entrance. So in essence, this turnstile was dual fare, dual denomination. This extra fare was collected to help offset the cost of the temporary subway line extension to the Fair Grounds, which was built at a cost of approximately two million dollars. At the conclusion of the World's Fair, only $500,000 in fares had been collected to offset the cost leaving the Board of Transportation to absorb the remaining balance. A similar "exit payment" style of turnstile was used from 1956 through 1975 on the IND Rockaway Line south of Howard Beach, and of which also collected a double fare in the means of an extra token upon exit; and for the time span listed. It is not known at this time if this 1939 Worlds Fare Model Turnstile were repurposed for the Rockaway Double Fare Stations, or a different machine entirely was placed into use.   |

|

||||||

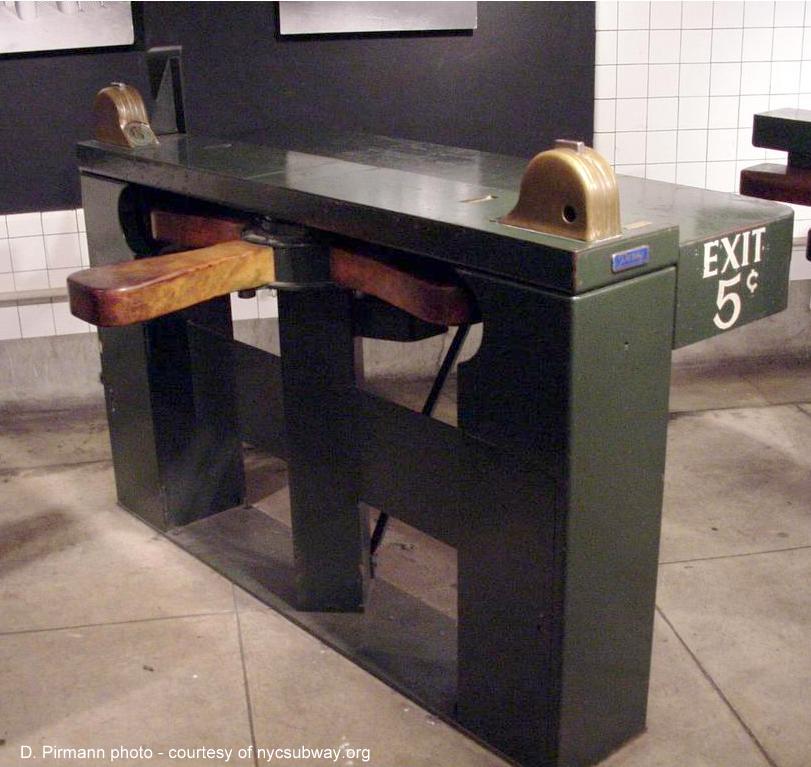

Perey Model 37 Square End Kompak - 1934

|

||||||||||

|

Purchased in 1934 for the BMT Division. 120 in service (1970) of which

110 are entrance only and 10 are two way operation (entrance and exit.)

A notable feature of the Model 37, is this design was the first to featured a three arm conical turnstile arm arrangement, with the hub mounted at a 45 degree angle to the ground. This design allowed for a significantly smaller footprint for the machine on the platform floor. These turnstiles were 27" wide, compared to the old style four arm turnstiles which were 43" wide due to the fourth wooden arm jutting out from the right side of the machine. These new turnstile arm configurations, eliminated the fourth arm entirely, and with it; the unused space required between turnstiles. Therefore another turnstile lane could be placed immediately to the right of this one, increasing passenger payment capacity. This saving of space allowed more turnstiles to be placed "en block" (several grouped together) and in a row, and hence increasing fare payment capacity for that location. This was especially beneficial in large stations, such as those at junction points or at terminals, that saw large amounts fare payment traffic. Simple, utilitarian, compact, easy to clean, easy to maintain. The Model 37 became the workhorse of the transit system. |

|

|||||||||

Perey Model 97 Round-End Kompak - 1946

|

||||||||||||||||

| Designed by

John

Vassos, a renowned industrial designer; of whom was hired to design

this new

streamlined turnstile by Perey Manufacturing. Streamlining

was en vogue, and Vassos applied the look to many items, including

Nedick's food outlets, RCA household radios; and the first television

and entertainment centers (TV - radio - turntable in cabinets). Mr. Vassos worked with other notable industrial designers of the time, including but not limited to: Henry Dreyfuss, Raymond Loewy and Norman Bel Geddes; but Mr. Vassos' name is not as well recognized as the others, as he refrained of opening his own firm. This design featured the conical turnstile arm arrangement as well, which allowing for smaller foot print space. This conical arm arrangement has become the standard configuration for future turnstile models. Another interesting fact about this model; it was designed for either one way operation (enter only) or two way operation enter and exit). This is because this would be the first model to be ordered by the Board of Transportation, after the first unification of 1940. As the IRT favored two way use (enter and exit) of turnstiles; yet the BMT and the IND favored one way turnstile use; (with exit via swinging gate at the token booth or HXT (High Exit) gates at unmanned locations.) Eventually is was decided to purchase all the Model 97's two way (enter and exit) and as far as is known, all 97's and later models were two way operation. According to New York Times newspaper articles, it is believed this model turnstile was retrofitted with a half dollar acceptance mechanisms for Aqueduct Racetrack Special service in 1959. In 1966 the half dollar was eliminated and the "Extra Large Y cut out token" was issued upon the increase in fare to 75 cents for the same service. In 1970; there were a total of 1085 of this model in service: 408 - single token, one way |

|

|||||||||||||||

Perey Model

107 - 1950's

|

|||||||

|

The next model in the evolution of conical arm turnstile. Design accents bear resemblance to the tail-fins and vertical taillights of 1950's automobiles. Its open bottom design under the turnstile arms facilitated better sweeping and mopping of the revenue area. Black. Chrome. Simple. Elegant. Mechanically, it shares coin acceptance mechanisms with the Model #97, however the turnstile cone is not compatible. With the exit of other turnstile manufacturers from the market, this model would become the the standard for replacement of older models, however; only 47 were placed into service. |

|

||||||

| Low Turnstyles | Perey Kompak (1 and 2 way) General Electric 4 arm, 2 way, electric American 4 arm, one way, mechanical Perey Coinpassor, 4 arm, mechanical |

|

| High Turnstyles | Perey - plunger type Perey - automatic American - automatic |

|

| Present Purchases; Low Turnstyles | Perey Kompak | |

| Present Purchases; High Turnstyles | Perey #45 full stride plunger type Perey Rotogates will eventually replace all High Exit turnstiles |

| fare media: | two quarters only | 1978 |

Duncan Industries Model

TC "Token - Coin" - 1980

|

||||

| This model is not to be confused with the earlier (1978) attempted conversion of unknown model of turnstile. This model of turnstile was an attempt to collect both tokens and coins within a single turnstile. While the kinks had long since been worked out for a multiple coin mechanism in a turnstile; many New Yorkers had been so conditioned to the single token, they were placing the token or quarters in the first slot they saw, and this gave them a 33 percent chance of choosing the correct slot: 33% chance of coin in token slot - 33% chance of token in coin slot - 33% chance correct object in correct slot! As such, the design was not successful. But this model saw the incorporation of smooth stainless case panels for ease of cleaning and did not require painting. In any event, the acceptance of tokens and coins made this turnstile a dual fare media. But kudos to the NYCTA Revenue Department for the attempt! |

|

|||

| Tomsed

Turnstile Company Model 110 - 1983 fare media: token 1983 - 2003 |

|

Not a great deal is known about this model, or its reason for installation. It could simply be a case of Tomsed being the lowest bidder for the contract. Tomsed is known to also manufactured the new stainless steel one way High Exit Gates. Perhaps a deal was reached where the NYCTA would take 5000 High Exit Gates, and 500 turnstiles on an approval basis, but this is unconfirmed. Brushed stainless steel case with minimal seams and smooth joints make for easier sanitizing, especially when the "token suckers" were at their height. Did not require painting and was better for keeping internal mechanisms free of dust and dirt. Tomsed was purchased by Boon Edam in 2005, a Dutch company that also specializes in gates, turnstiles and other revenue controlled access items. Research will be forthcoming. |

|

AFC

Turnstile (Cubic) Automatic Revenue Collection Group - 1992

|

|||||||

| This turnstile was released into public use initially as a token only machine in 1992. However, its original design was fully intended to be, and was upgraded to include; an electronic fare payment method such as the MetroCard, when said system rolled out at a later date, which was 1997. In taking tokens and MetroCard, made this turnstile dual fare media. These turnstiles were also designed to deter fare-evaders by turnstile jumping. The sloped top caps on left and right prevent a flat and level placement of hands, and the inverted U tubes and uprights towards the exit, limit the headroom and arm placement when hopping over. As always, the determined fare evader still found ways to circumvent paying their fare, but the instances were reduced. These are the last turnstiles to have been built with token acceptance in mind. Again, stainless was the material for the case. With the abolishment of token use in 2003; the token slots were capped and this machine became MetroCard Only. The machines are expected to have the internal MetroCard computer readers exchanged for OMNY computers and RFID pads mounted on top by 2024. These would be the last turnstile model to accept tokens and therefore is the final model applicable to the coverage of this website. |

|

||||||

| Perey Model #45 (full stride) "Coin Passor" High

Entrance Exit Turnstile "HEET": ca. 1945 - the "Iron Maiden" Perey Manufacturing

|

||||||||||||

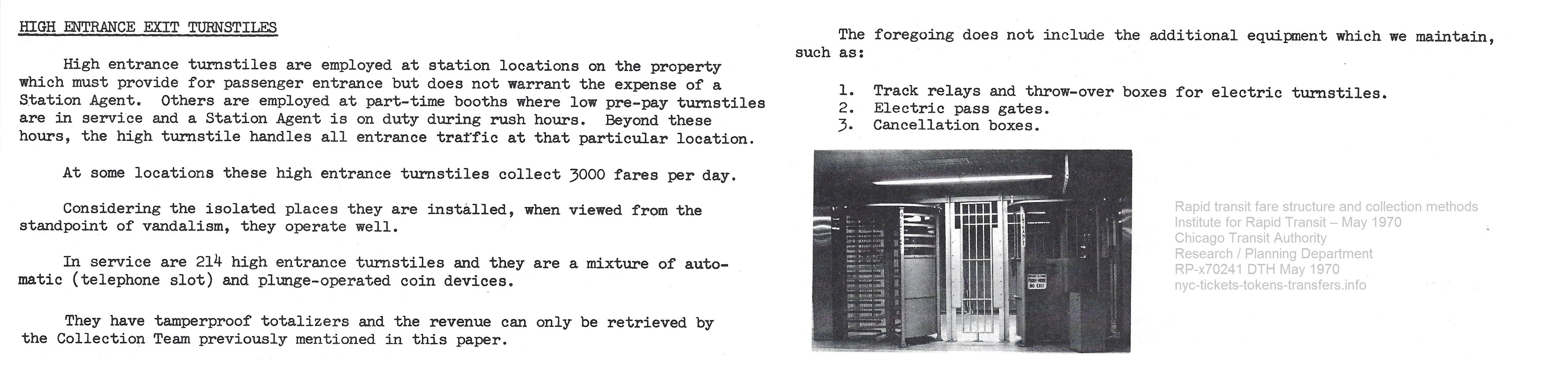

|

Perey Manufacturing model 45 full stride "Coin Passor" - ca. 1945 (not shown) American Turnstile 1931 - ca.1945 These turnstiles were coin - mechanical operated from 1945 to 1953 and then operated by tokens (only) after that date. A farepayer deposited a coin or token into the slot on top, and then pressed a plunger inwards from the front, which released a mechanism which allowed the passenger to rotate the turnstile while entering. After 120 degrees of rotation, the turnstile locked, until the next coin / token deposit and plunger activation. These are used at low traffic egresses of stations, where token booths may have been part time, or a passageway where a change or token booth may have been impractical due to space restrictions. In another consideration for their use, was when budgetary shortfalls became common place within the transit system in the late 1960's through the 1980's; these High Entrance Exit Turnstiles could be installed, replacing a part time or full time change / token clerk position. Collection of tokens was done by Collection Agents, not by Station Agents (Token Clerks) |

Plunger Mechanism |

||||||||||

1970 "Rapid Transit Fare Structure and Collection Methods" published by the Institute for Rapid Transit (U.S.) |

||||||||||||

High

Entrance Exit Turnstile "HEET" - 1993

. |

||||||||||||

| Perey Rotogate? One Way High

Exit Gate "HXT" media: none |

||||||||||||

|

This is called a High EXit

Turnstile; but technically speaking, it

is not a turnstile. It is a one way gate, as there was no method of payment to enter through the device from either direction. The design incorporates a one way ratcheting mechanism to prevent unpaid entry, but freewheels in the exit direction. Inclusion here is because their use often coincided and were mounted next to or in close proximity to the High Entrance Exit Turnstile model above. As a kid, they could be fun to lock your little brother or sister in, by holding the bars from moving further once they were in the wedge shaped area where they could neither get in or get out; until a quick smack from your mother made you let them out. ☺ They remain significant hazards in cases of rapid evacuation, such as smoke conditions, fire, rapid flooding, derailments, acts of crime or terror attacks. But, as they are strictly mechanical, they work in loss of power conditions. |

|

|||||||||||

|

| Turnstile technician

with vernier caliper performing maintenance on a Perey Kompak

Round-End Model 97 - 1975 image courtesy of the New York Transit Museum image archives |

![]()

Model D - Manual |

But

with the advent of the

internal combustion bus, bus stops were relocated to the curbside out

of traffic lanes and now drivers had to steer the bus in and out of the

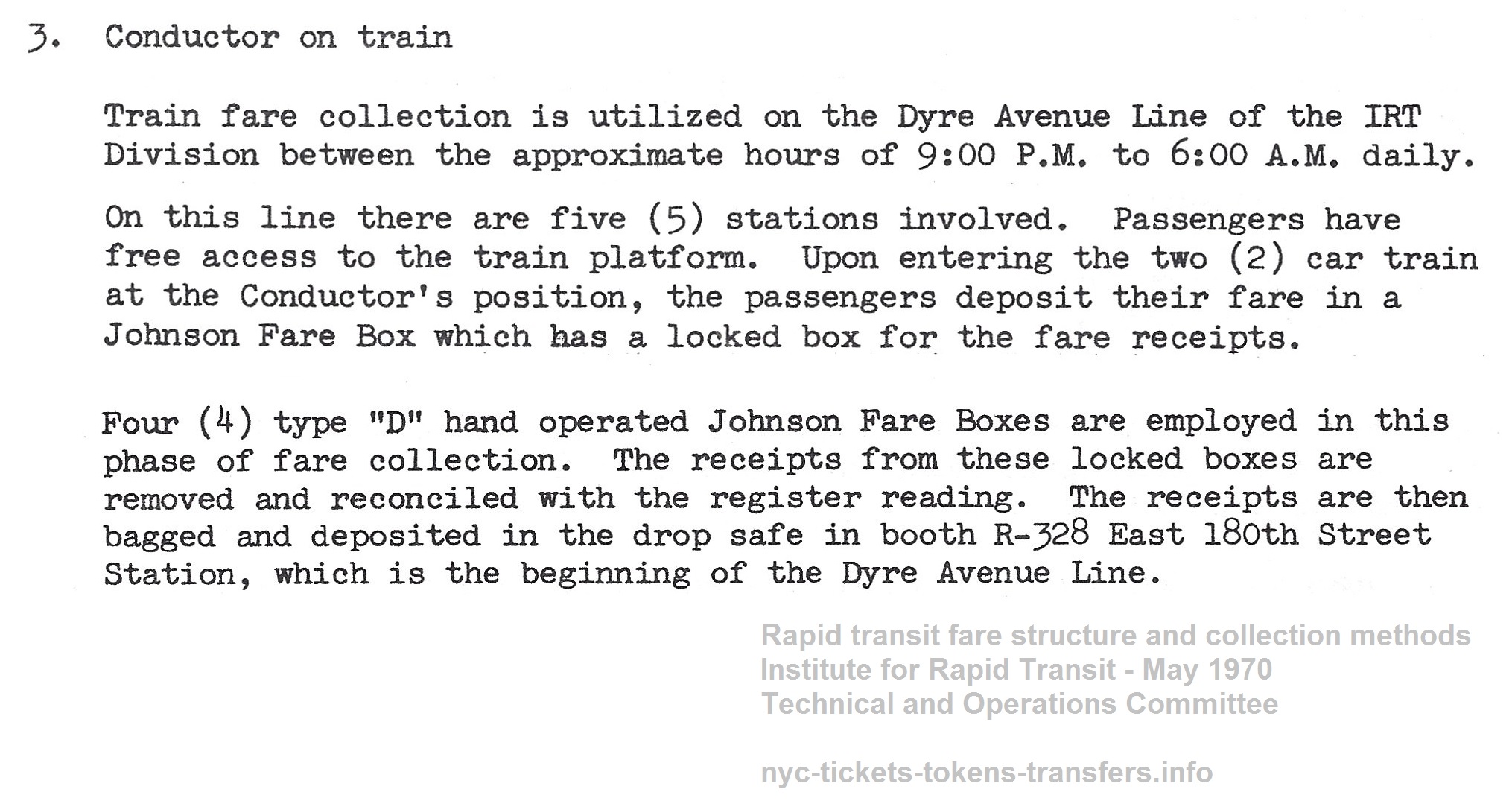

stops as well as swerve in and out of traffic. When considering a bus driver had to collect fares, make change, issue transfers, collect transfers (and make sure they were valid on both date, time as from an appropriate connecting route), keep tallies of same; on the rare occasion assist a passenger in boarding or alighting from the bus, let alone actually driving the bus (especially in congested traffic), making change was a distraction that could be eliminated. Especially when a passenger realized last minute they needed change or a transfer for a connecting line and the bus was already moving towards the stop! Driving and making change did not make for a good combination, but they did it. Early fare boxes had a crank on the side that the driver had to rotate (like a coffee grinder) to sort and count the change which then dropped into the coin box below. In New York City, these were the Johnson Farebox, Manual D Model and can be seen at left (please note: this is the only the upper sorting and counting portion only; the coin box / pedestal is not seen in the photo.) Note that the Model D did not accept quarter dollars - only pennies, nickels, dimes and one size of token. IRT Dyre Avenue Line Collection Method

It was most interesting to learn that the Model D was used on board subway cars of the IRT Dyre Avenue Line for fare collection between the hours of 9:00 pm and 6:00 am daily! 3. "Conductor on train Train fare collection is utilized on the Dyre Avenue Line of the IRT Division between the approximate hours of 9:00 P.M. to 6:00 A.M. daily. On this line there are five (5) stations involved. Passengers have free access to the train platform. Upon entering the two (2) car train at the Conductor's position, the passengers deposit their fare in a Johnson Fare Box which has a locked box for the fare receipts. Four (4) type "D" hand operated Johnson Fare Boxes are employed in this phase of fare collection. The receipts from these locked boxes are removed and reconciled with the register reading. The receipts are then bagged and deposited in the drop safe in booth R-328 East 180th Street Station, which is the beginning of the Dyre Avenue Line." |

|

| The next farebox to be installed on NYCTA buses were Johnson

Model

K25 seen at right. These were simplified for operation with

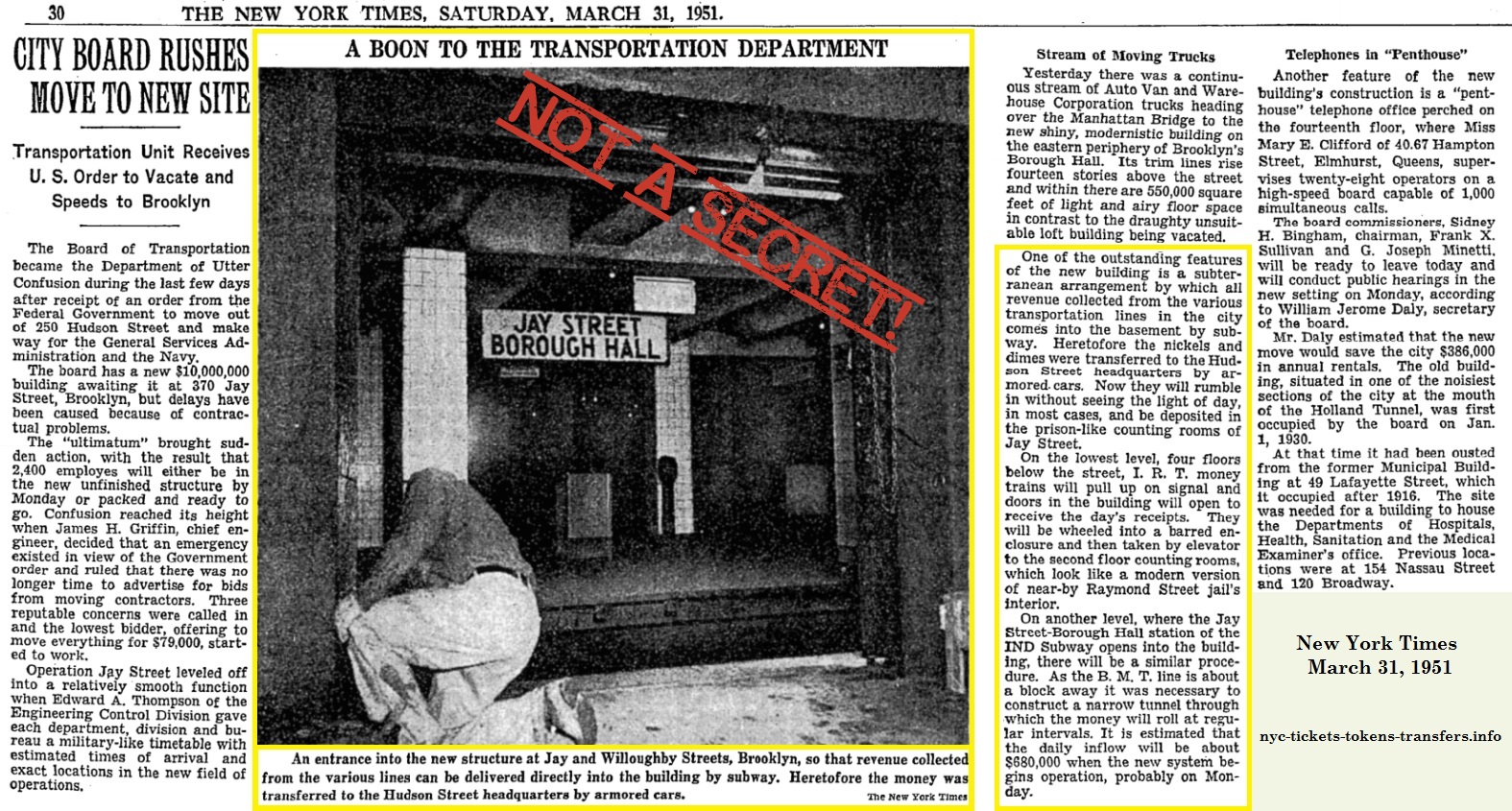

the