MoPac History

|

|

Sources:

Missouri Pacific River and Prairie Rails - the Missouri Pacific

in Nebraska by Michael M. Bartels

this book is invaluable with it's information of the MoPac's history

in Lincoln, as well as all of Nebraska

The

Hub of Burlington Lines West

by Holck

The

Lincoln Star & Journal

Special

Thanks to William W. Kratville, Glen

Beans, James Gilley, Michael Bartels,

J. J. Holck, and Jim McKee for letting me borrow from their photos

and research.

Every effort has been made to get the correct information on these

pages, but mistakes do happen. Reporting of any inaccuracies would

be appreciated.

All photos & text © 2000-2008 T. Greuter / ScreamingEagle@rrmail.com

unless otherwise noted.

|

|

|

|

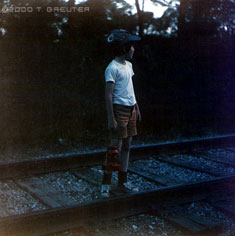

Being

all of 7-years old, I didn't know or care much about history. But

I did know that I was enthusiastic about trains. As far as I was

concerned, ALL engines wore Jenks Blue with the white stripes on

the nose that reminded me of "warpaint", and a huge white

eagle with claws outstretched and screaming on the sides.

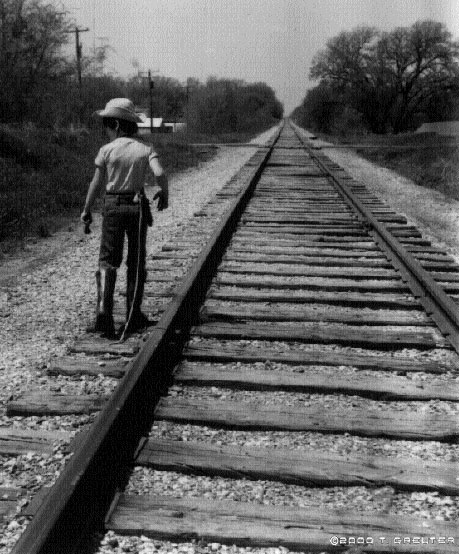

As

I walked the rails in cowboy hat and boots, I didn't know all of

the story. But as I reached down to pick up an ancient cinder/clinker

my mind drifted to what it must have been like riding these rails

long, long ago.

Lincoln,

Nebraska - 1977

|

Westward

to Lincoln!

With the coming

of the Missouri Pacific to Omaha and its stockyards, it became a major

goal of the city of Lincoln to bring the railline closer to home, not

only for the benifits of competition to the other carriers, but to gain

access to southern lumber and coal. After years of talks, in 1886 the

Missouri Pacific laid track through the towns of Nehawka, Wabash, Weeping

Water, Elmwood, Eagle, Walton and Lincoln, Nebraska. Wabash and Eagle

came into being and flourished as a result of the new track being laid.

In fact, the Dec 30, 1888 issue of the Daily Nebraska State Journal

would proclaim that the MoPac had led to quite a bit of the prosperity

seen in Lincoln over the preceeding three years. The connection to southern

resources had indeed been fruitful. This branch line connected at Union

to the Omaha line, and the growing Missouri Pacific Railroad system.

Traffic from Omaha and Kansas City could reach these young communities.

The carrier originated from Missouri and constructed parts of its trackage

in Southeast Nebraska as subsidiary companies to the MoPac. Eventually

about 347 route miles would operate in Nebraska.

|

A

mileage marker just west of Eagle marks the spot where the Union

and Lincoln extensions were joined. 5/13/95

|

|

The Missouri Pacific

had staked it's claim in Lincoln. The original idea was to have the

line push westward, and this got as far as the Union Pacific connection

on the salt flats west of Lincoln (interchanging with UP continued here

until the merger). In the early years the rail business boomed with

transporting grain, livestock, coal, limestone, and lumber.

The 1870's and 1880's

were decades of rapid growth for small towns such as Weeping Water on

the branch or Falls City in far southeastern Nebraska. Weeping Water

experienced a building boom, with the name "Missouri Pacific"

being adopted by not only a new hotel, but also the town's baseball

team. Meanwhile down in Falls City in 1871, the coming of the Atchison

and Nebraska Railroad accelerated the town's growth, while in 1881-82,

the Missouri Pacific mainline from Omaha to Atchison, Kansas opened.

In 1909, Falls City became a division point on the Missouri Pacific

Railroad. This improved transportation access helped Falls City grow

from 607 in 1807 to 3,022 in 1900.

Weeping Water was

not only at the heart of the Union to Lincoln branch, but had become

a Missouri Pacific crossroads in 1887. Before the track to Lincoln was

finished, crews began clearing a right of way up north to Omaha and

down south to Talmage for a connection to the Crete Branch. Meanwhile,

up in Omaha the MoPac was encircling the whole city with it's own belt

line. It continued the use of UP's Omaha facilities but would no longer

merely be a "guest" of the Union Pacific there.

In 1881 The Missouri

Pacific made another stab in Nebraska further west. After some controversial

stock wheeling and dealing by rail giant Jay Gould, the Union Pacific

had aquired the Central Branch R.R.

in Concordia, Kansas - thus driving out the competition from the Kansas

Pacific R.R. The Union Pacific then leased this track to the MoPac,

which had access to Concordia by it's own line. The MoPac's aim of extending

farther west had taken another step forward. Eventually the Missouri

Pacific aquired the interest and began laying track extending northwest

from Warwick, Kansas to Prosser, Nebraska in 1887. Prosser experienced

a boom with it's own streetcars and a cotton mill, but the railroad's

aspirations languished as efforts to push up across the Platte River

and on to Kearney failed to make progress due to the lack of support.

|

| Lincoln's

Union Station, jointly operated by the MoPac and C&NW, as it

appeared sometime after the turn of the century - from a postcard |

Being the northernmost

extension of the railroad, the Missouri Pacific had to face new natural

foes as well as the man-made kind. Such was the challenge of Nebraska's

unpredictable weather, which seems to prefere the extreme more often

than not... flash floods and tornadoes, grassfires, or fighting to keep

the trains from becoming snowbound during heavy snowstorms, such as

the infamous Blizzard of 1888 which prooved deadly all across the plains.

In October 1887

work began on a new brick and sandstone passenger station at Ninth and

S streets west of the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, replacing a

small frame depot. With it's Baroque style spires the new station was

decidedly a bit more elaborate than the old structure. The MoPac shared

the facility with the Freemont, Elkhorn & Missouri Valley (later

the Chicago & Northwestern) as well as some jointly operated rails.

The cooperation between the two lines would continue until the C&NW

ceased oprations in Lincoln, an arrangement that lasted 95 years. The

station came to be known as Union Depot. It was the only one in Lincoln

at the time to be used by more than one rail company. Three years after

the new passenger station, both companies moved into their new freight

depot just to the west. Though station facilities and rails were shared,

the MoPac and C&NW mantained their own additonal yard spaces and

engine terminals, surrounded by lumber warehouses, coal industry companies,

and other commercial dealers.

Railroad

Stories

There are a couple

of intriguing stories involving the MoPac in Lincoln. One story concerns

a dispute involving crossing rights which threatened to become down

right ugly back in 1890 on August 25.

The Missouri Pacific,

the Burlington & Missouri River (a predecessor of BNSF), and the Fremont,

Elkhorn & Missouri Valley (now an excursion line) were miffed at the

North Lincoln Electric Railway. The electric streetcar line, in preparation

to enter northern Lincoln, laid track between two tracks of the MoPac

near 11th and W Streets. The superintendent for the Burlington (who's

tracks paralleled the MoPac) and the attorneys for both the Elkhorn

and the Missouri Pacific were soon at the scene of the "crime".

Then the 3 railroads had moved their locomotives accompanied by a force

of 200 men to join the dispute. The stand-off lasted hours with both

sides glaring and trading insults, but gradually kept enough of their

cool, deciding to resolve the issue in the courts instead.

|

The next day, the

26th, a judge issued a restraining order against the railroads, prohibiting

them from interfering with the streetcar line. But by the morning of

the 27th, the streetcar company charged four Burlington officials with

disobeying the restaining order.

Now things got worse...

That afternoon the

sheriff and a deputy were called out to the disputed site. They found

the main and side tracks again occupied by the railroads' locomotives.

When ordered to move off the crossing, the engineers would only move

one locomotive at a time, constantly leaving one to block the track.

The engineers were arrested, a skirmish ensued again threatening to

become bloody, so the sheriff swore in 20 deputies armed with revolvers

(including some of the streetcar company men). The crowd was driven

back. Then a fireman had to be overpowered in order to move an engine

off the crossing, amidst cheers and jeers. The railroads were defeated,

but they left the spaces between the street car track 'paved with rails'

Accidents were a

common occurance on any railroad. Such was the case of a "lost"

train. In January 1911, a MoPac road crew unfamiliar with Lincoln left

early one morning, not realizing that the track switch was aligned for

a C&NW passenger train. The C&NW roundhouse took notice of the

unexpected sight rolling by and notified the tower at North 27th Street

to flag down the wayward train. Fortuantely they were stopped, and face

to face with the C&NW passenger train!

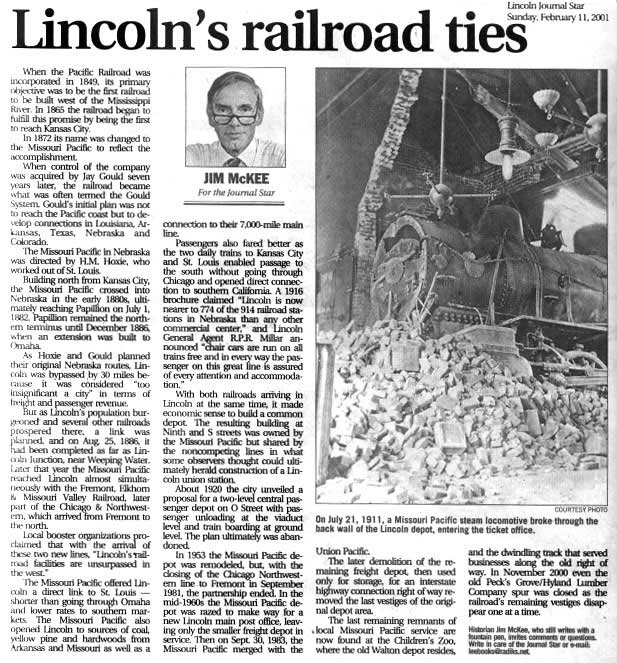

On July 21, 1911

the operator of a MP 4-6-0 somehow either lost balance from the cab

and fell off or jumped off to throw a switch and couldn't climb back

on the moving engine (the stories conflict). Anyway the results were

the agreed to be the same as the unmanned loco made an unscheduled stop

through the wall of the C&NW ticket office. No injuries occured,

but tickets were strewn all over among the rubble as employees rushed

to collect the booty.

There were a few

other encounters. Sharing a busy railyard in the age of steam was no

easy matter... and there were times when the foremen of the two companies

were said to have had skirmishes. But overall the MoPac and C&NW

crews worked well together.

The

City and the Railline Grows

|

| MP

724 - The 2-10-2 literally fills the sky with hot steam on this

frigid 21st of January day, 1951. It would be one of the last times

steam would be seen on this mainline, as #1724 pulls a freight northward

near Lake Street in Omaha, Nebraska - photo © copyright William

W. Kratville, used with permission |

Peck's Grove, a

farm and orchard east of 33rd Street in Lincoln grew into a community

thanks to the MoPac's service to the college town. This area of open

farmland was subdivided into residential lots, and a depot was erected

by the Fall of 1886. Later on, by the 1920's, the depot would be reduced

to a shed With the coming of the postwar years a sign continued to mark

the stop, long after the city of Lincoln swallowed up the one-time farm.

And even then it was still used as a stop for neighborhood residents.

There was another flagstop farther on east to serve Bethany Heights,

another new developement around a new college, with it's depot located

at what is today's 66th Street. MoPac's motorcars were a common sight

during these years. The Bethany Heights building stood long after it

outlived it's use as a depot, being converted to an elevator scale house

in the Twenties. By then the growing city of Lincoln annexed this area

as well.

The coming of the

Burlington's Zephyr meant a new source of stiff competition facing the

Missouri Pacific in Nebraska. By August 1937 Lincoln saw its first diesels

in road service, a pair of NC2s #4100 and 4101, although appearing to

be switchers, these were painted up in the early road colors of black

with white trim (over the years MP would modify a number of switcher-types

including the addition "streamlined" cowling over the front

end reservoirs for road service). One of the new diesels handled one

or two daily passenger runs to Union, while the other switched in Lincoln

during the day, and ran round trip freight to Union at night. The countdown

clock had begun for Steam on the branchline, but not until 1951 would

the last fire would be put out.

WWII

Legacy

During wartime the

Missouri Pacific participated in the building of the Martin bomber plant

near the Fort Crook, Nebraska station. The forty-eight new buildings

constructed as well ast the airstrip were leased to the Martin-Nebraska

Co. (an arm of Glen L. Martin Co.).

Martin used the

facility to produce bombers and other aircraft. At it's peak, the Martin

Bomber plant employed 14,500 workers and turned out over 2,000 war planes,

1,585 B-26 Marauder bombers, 531 B-29 Super Fortress bombers and modified

over 1,000 other aircraft. The best known bombers of the War were products

of the Nebraska plant - the famous B-29 Enola Gay and Bock's

Car which dropped the atomic bombs on Japan and brought an end to

World War Two.

After the war, was

leased to the Army and processed prisoners of war. In 1946 the airfield

was designated as Offut Field by the Army Air Corps, ultimately becoming

Offut Air Foce Base. The former bomber plant was transformed once again

for an even bigger role, converted into the new headquarters of the

Strategic Air Command (SAC).

|

| A

scene once common now gone. Caboose #13408 rounds a rural curve

at Omaha, Nebraska. "Schoolhouse Bend" as pictured by

reknowned photographer William W. Kratville - © W. W. Kratville

photo, used with permission |

Growing

up in the 40's and 50's with the Eaglet

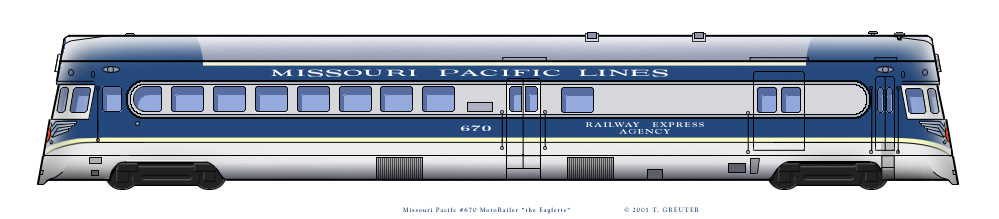

It was Feburary

1940 - Lincoln was close enough to the route of the Mopac's new streamliner

to be treated to a visit by the pre-inaugaral tour of the Eagle... even

though the Eagle didn't make a direct connection here. Excitement would

continued to be high, even billboards advertising the sleek streamliner

began to appear in town. Soon passengers would make a short trip from

Lincoln to board the new Eagle at Union. By September 1942 a double-ended

streamlined Motorailer No. 670 built by ACF was put into service on

the Lincoln branch as a compliment to the Eagle. Resplendant in attractive

blue, gray and yellow border matching those of it's now-famous parent

the motorcar was nicnamed the "Eaglette" or the "Little

Eagle". Operations required a crew of four - the railway express

agent, conductor, brakeman, and engineer. Inside its passengers were

treated to the comforts of the streamliners traveling at a sometimes

bumpy 55 mph with unequalled railtravel views from it's glassed front.

Occasionally standard motorcars or a steam engine would fill in when

the "Eaglette" was unavailable. Over a course of the next

12 years this motorcar captured the attention and hearts of Lincolnites

and came to symbolize the Missouri Pacific between Union and Lincoln.

When there was talk of its retirement in 1952, local outcries, plus

MoPac's chief executive officer Paul J. Neff brought it back into service

for another 2 years. The poor soul who originally suggested the retirement

idea was demoted.

|

|

MP

670, the 'EAGLETTE' MotoRailer - © copyright

T.

Greuter

|

The Eaglet was a

definite hit with the local kid population, achieving fame that would

outlast it's all too brief career. A Lincoln-native now living in Eagle,

Bob Soflin writes "I grew up in Bethany Park in the 50's... along

the banks and in the depths of "Dead Mans' Run" ... where I used to

fish for crawdads under the creek bridge between Cotner and 66th South

of Vine. The banked curve between 56th and Cotner offered many hours

of pleasure walking the rails waiting for the Eaglet and the daily freight.

When no trains were expected the creek offered a diversion and when

that didn't entertain us we chased wayward golf balls on nearby Park

Valley Golf Course. "

"I loved the

Eaglet and knew when she was coming every day. I got to ride her to

Union and back twice before they took her off. I also remember seeing

some steam freights and one time a circus train came through. "

But of all Bob's

memories, one image stands out among the rest, "As the Eaglet approached

Cotner from 56th to me it was the most beautiful thing I ever witnessed."

Dieselization Brings Big Changes

May 16, 1948 saw

the coming of the Freedom Train to Lincoln, filled with historical artifacts

being exhibitted across the country. While parked in the MoPac's passenger

depot it was visited by 8,241 people. In a few short years the towering

spire and intricate designs would themselves pass into history as the

old station was replaced by a smaller, more modern facility in April

1953.

|

|

A

MoPac train passes behind a new suburb in the 48th-56th Street

area in the early 1960's. It still looking more like the farmland

it was when the line was originally built. This area will change

greatly from development over the next 10 years.

|

Big changes were

happening by late 1951. The ever forward-looking Missouri Pacific was

the first of Nebraska's major raillines to completely dieselize. This

meant jobs were cut back, the city-scape changed with the disappearance

of water and coaling towers and roundhouses. Even roads in Falls City

were affected as the city lost its source of cinders used on it's unpaved

streets. MP 486, a 2-8-0 was the last MoPac steam locomotive out of

Lincoln.

Nine years after

replacing the granduer of the old station, the modern joint MoPac/C&NW

passenger depot in Lincoln was itself demolished in 1962, with operations

moved to a freight office space the two railroads shared with a beer

company. For years the station was the departure point for trains, motorcars,

provide passenger service to and from Union, Nebraska to meet the sleek

Missouri River Eagle streamliner. By July of 1954 a Missouri Pacific

bus would take over the The Eaglet's 12-year assignment, with the motorcar

being moved further south to work in the warmer climate of Louisiana,

where Nebraska's deep snows couldn't lock it up in an icey grip. Depots

were disappearing in Elmwood, Eagle, Union and to the south in Talmage.

And eventually, like the others, the newest Lincoln freight office was

gone to make room for the highway overpass of Interstate 180 by 1986,

leaving only a few tracks as reminders under the new concrete bridges.

|

|

MP

213

and Chicago & NorthWestern 1545, - the Geeps offer comparative

views while switching cars at the joint MP/C&NW yard a stone's

throw from Memorial Stadium in Lincoln, Nebraska. The date is

April 19, 1974. - © copyright Glen Beans, used with permission

|

Over the years the

MoPac kept a solid presence along the branch line. The daytime switch

engine crew would build a train at Lincoln to be taken by a road crew

to Union, then back to Lincoln. In 1963 the late evening departures

were moved up to late afternoon... around 5 p.m., in order to get the

road engines back in time for the switch yard crew the next morning.

The railroad ran everything they had into Lincoln at some time or another,

but they did have some preferances for the branch. By the late1970's

the equipment had changed many times - gray and blue had long since

given way to solid blue for economy back in 1962. A pair of sleek new

GP15's or slightly older GP38-2's had replaced the aging GP7's and F7's,

which before them had replaced the varied mix of steam driven locos

like the Ten-Wheelers, the pride of passenger crews on the branch in

the 30's. But always the service continued as it had everyday except

on Sundays, a traditional rest day. Occasionally the day off was changed

for football Saturdays, and operations were suspended due to the Mopac's

close quarters to the University of Nebraska's Memorial Stadium... a

very wise decision in light of the crew's challenging efforts to switch

cars among rabid Big Red fans. When the city wished to expand "O"

Street to four lanes, the railroad replaced it's bridge over the street

in July 1971, becoming the largest rail landmark in town. For awhile,

a pair of new MP15ACs yard switchers, #1533 and 1532 were seen building

trains in the Lincoln yard during 1974. By the mid 1970's the through

train, #171 and 172 were performing the local switching operations.

The Lincoln switch crew was discontinued service in July 1975. This

left one train to do everything, occasionally with a switch crew being

brought back briefly during times of heavier traffic.

|

Growing

up in the 70's with a railroad in your backyard

Five o'clock p.m...

except for the caw of a jay in the surrounding trees growing upon the

isolation of the surrounding hills, all was silence. This was another

world apart from the everyday suburbs hidden all around. Then in the

distance you'd look up, and there it was... a bright glimmering point

of light shining. We knew what it meant. It was coming! Not much longer

you could hear the horn blast and the light rose higher as it approached

the 48th Street bridge heading straight toward east. Now you could make

out a shape around the light. When the air and the ground both began

to rumble from the throb of EMD turbine engines, it seemed that any

kid on the block who wasn't already outside would rush out the backdoor

of their home to watch and wave.

As a kid, my family

lived close enough to the MoPac's Lincoln-Union line that you could

feel ground shake as the train passed. The MoPac was an overwhelming

sight of white warpaint (that's what the white nose chevrons reminded

me of), buzzsaws and billboard-sized screamin' eagles on the long hoods...

endless loads of graincars... trailers on flats of every color and boxcars

from all over the country. Sometimes we'd see loads of military tanks

or other vehicles on their way to the Nebraska National Guard. One engine

was affectionately known as "the Greaser", due to all the

oily residue clinging to it's sides. If we were quick and rich enough

we could crush a penny under the wheels of the heavy engines (the all-copper

pennies minted before '72 worked best).

|

MP 1624 with her brakeman at the ready, the little GP7 rumbles

through the UNL campus on a clear white day in Lincoln, Nebraska

on March 5, 1976. Later it will make the 5pm run east to Union,

then back home to Lincoln around midnight. - © Glen Beans

Photo

|

Always there was

an enthusiastic wave from the conductor in his bright red caboose, he

must have gotten a swollen arm from all the waving he'd do each day

as he saw us fly past from high above in his cupola. We'd stand and

stare as the train rumbled away, going over the hump past at 56th Street,

until it was no longer in sight. The smell of diesel still hung in the

air as we turned back to our bicycle races or tv cartoon shows. Or maybe

just a few of us stayed behind, as we would search the gravel around

the rails for our newly flattened penny with all the wonders of the

smoke and noise of the MoPac still playing in our minds.

Mom always tried

to persuade me away from the rails, telling me if I got too close I'd

be sucked under the wheels. I didn't believe her... no engine traveling

at 20 miles an hour could do that. But still I always used caution whenever

near my stretch of track. Better to have a healthy respect and not to

push your luck with any train - you'll always come out the loser.

Now I'm not here

to defend what a bunch of us kids in my neighborhood did way back when

(if and when dads and moms found out our gooses were usually cooked

too). And I'm sad to say some of what we did was pretty stupid, even

for kids. I will confess that we took advantage of our apple tree and

delighted in using a passing hopper empty for target practice (locos

or cabooses were off limits) - the empties boomed like a humongous drum,

a pretty big sound for a little kid to make. Yes, we could be brats

at times... and darned lucky that no one was hurt either on the train

or the kids. There was always someone laying a rock or a branch or even

a spike on the rails just to see the aftermath of it being squished.

I lived directly beside the tracks, and I kind of had different ideas.

I had my own little patrol on the rails every day and knock any obstacles

off... sometimes rocks or 2x4's or fallen trees. A train derailment

into all these surrounding homes wasn't going to happen under my watch!

This wasn't the

only type of mayhem the neighborhood kids got into. Around about the

4th Grade, a friend of mine who we'll fictionally call Greg the Schemer,

had hatched a scheme to collect old rail spikes then selling the metal

to a scrapyard. Now there was always this rumor going around with us

kids for as long as I could remember - that rail spikes were worth their

weight in gold and ripe for the picking. Many had tried and all had

failed. But Greg had a plan. So after the school bell rang at 3:00pm

he ran out of the schoolyard to the rails nearby and began hunting for

spikes that had worked their way loose or had fallen off. The secret

to Greg's master plan was wearing his extra baggy jeans with big pockets

that day. With much sweat and toil, Greg pulled spikes and filled his

pockets with all the booty he could carry and with a noticeable swagger

he trotted off home. In his head I'm sure he happily dreamed of how

to spend every last cent of his soon to be had riches.

Then along after

5:00pm rolled by, not long after one expects all the neighborhood fathers

have gone home from a hard day's work, I happened to spot Greg back

working on the track. This time he was under very close adult supervision.

I couldn't hear what was said, but I imagine it was just as well. The

stern looking figure would point to the rails, then stand with hands

on hips and the poor Greg the Schemer pounded every spike he pilfered

into the hard cross ties with a small hammer. Oh the humiliation...

another great kid-idea bites the dust!

|

Sublettered

for Mopac subsidiary Texas & Pacific, #13103 is parked on the

college campus at Lincoln, Nebraska in October 1975. This evening

it will be headed back east to Union, then it or a sister will

make the return back again to Lincoln around midnight - ©

copyright Glen Beans Photo

|

At times the railroad

would bring on a few troubles itself. Now the trackage east from 40th

Street straight over the 48th Street concrete bridge, past the schoolyard

through to 56th was free from any crossings save for a single school

sidewalk. There

were times when the local crews were either faced with an over-full

yard or busy switching out cars, so thier solution was to park a long

cut of freight cars between 40th and 56th Streets (either for a few

hours in the morning, or since the previous night).

This gave the crew

a huge stretch - longer than the yard itself - to park cars without

impeding road traffic. Busy 48th Street now ran under the line (I believe

that the grade seperation was constructed around the 1950's). Unfortunately

someone didn't take into account the school kids who used the sidewalk

crossing the tracks to reach Riley Elementary School. Ten minutes before

the school bell rang at 9 a.m., kids everywhere were crawling through

the parked cars, under cars or tried to find a way around, oblivious

to the danger. Then pretty soon the cars would roll without warning

as the crew would finally clear the sidewalk The freight office received

some very pointed phonecalls those mornings.

The MoPac always

offered hours of entertainment for us kids, even when they were not

running trains. Finding old date nails imprinted way, way back in the

1920s and '30s was fun. We made it a competition to see who could find

the most colorful rock from the ballast bed - the ones with a bright

stripes of rusty orange mixed with black on white where more valuable

than diamonds, especially if it had a vein of glitter in it. The biggest

prize however were the ancient klinkers and coal cinders, perhaps dropped

off of one of the ten-wheelers that used to call Lincoln home. These

were sometimes bigger than both fists put together and reminded me of

something as exotic as a meteorite.

After a MoW gang

had been through our area performing some trackwork (the spreaders and

pullers put on an impressive show) we'd have fun picking-up the discarded

items, an empty track nail drum could always be used for an addition

to the clubhouse, and it was always cool to find a bent spike in the

shape of an "L". One lucky day I found a spike driver with

a split handle thrown into the weeds of a hillside - I still have that

relic today. The most exciting bit of equipment I was fortunate enough

to play with for some time was the speeder that a crewman parked behind

our home. I spent a whole weekend in my engineers cap and bandana playing

on that thing, waving off any possible dangers with a lantern and sounding

an imaginary airhorn.

As kids we'd sometimes

lay out on the dirt hill beside the right of way with our bikes, chewing

on a stalk of grass straw and wait for the train to come. To pass time

we'd have a Railwalking contest to see how far we could go before loosing

balance - I had alot of practice at this. There were always trestle

bridges and culverts with a little creek to explore. But we had to always

keep an eye on the horizon for a bright little speck of light. The line

was flat and straight enough that you could see a train approaching

miles away, long before you could hear the horn. As the engineer saw

us gathered to wave he'd give a blast of the horn or ring the bell which

made us jump and cheer.

|

MP 2032, a GP38-2, which appears ready for the eastward run to

Union from Lincoln, Nebraska on March 5, 1976. - © Glen Beans

Photo

|

To give

a brief idea of rail operations in Lincoln during the years of the 1970-80's,

MoPac had direct access to many local industries. Lincoln Lumber and

Hyland Bros. - both lumber industries were located between 33rd and

20th Streets. Cushman Industries - renowned manufacturer of Cushman

golf carts, motor scooters, etc... was another major industry directly

linked to the line here. East of 17th Street the line crossed the CRIP

and the local switching company OL&B, who handled two of the larger

grain elevators in the city, as well as the Reimers-Kaufman/Ready Mix

plant which kept shipments of sand, gravel, lime & cement in constant

demand. Just west, north and northeast of Memorial Stadium the line

became the joint MP/CN&W rail yard. Here the two roads interchanged

freely and shared the freight office as well. Just southwest of the

yard were the team tracks, Lincoln Station, and the Haymarket district

where the MoPac interchanged with BN and UP. Finally the line terminated

into the UP line west of town and west of Salt Creek. Passenger

traffic was long gone, but the twin daily runs was as routine as day

and night.

|

|

MP

#1547, a MP15

DC, switching cars at the joint MP/C&NW yard near Memorial Stadium

in Lincoln, Nebraska. Though it's November 1974, from the looks

of the bright red engineer's cap, it's easy to imagine things

haven't changed too much since the days of steam power. - ©

Glen Beans Photo

|

As a kid, the almost

endless summers of discovery of the tracks always held something for

us, whether it was the mechanical mystery of a work train plodding by

one day... or playing engineer on an orange pushcar parked behind my

home the next. Just about midnight the engine would make a return run

from Union back to its roost near Memorial Stadium. You could hear it

coming from a greater distance during the stillness of the night...

I could trace it's path past Cotner Boulevarde, then 56th Street in

my mind. The ground would vibrate and the windows rattle as the powerful

EMD engines got closer. I'd rise from my pillow and peek out my darkened

bedroom window that faced the track to see the sillouttes rush by as

a multitude of dancing "lightning bugs" signalled off and

on, as the familiar shapes made the track whir with the many steel wheels.

Some may think it a shame that we missed-out on the age of steam, but

us kids didn't care. Those were the best and biggest toys we ever had.

This was my world.

Merger

- the Big Mop-Up

Oftentimes the

MoPac would be seen cooperating with the Burlington Northern (formerly

the Chicago Burlington & Quincy), which had always been the rail

king in Lincoln. The cooperation was not only seen in Lincoln but across

both systems. The MoPac's philosophy saw a time of increased rail mergers

coming, and was determined to find an ideal partner to merge with rather

than be left behind in the future. The MoPac was always looking ahead.

Other roads such as the Rock Island had slipped here and withered away

into non-existence. Ultimately the prospects of a BN/MP union fell through,

as the the two systems overlapped and duplicated too many operations

to be profitable. The MoPac then turned it's eyes to the Omaha-based

Union Pacific and things began to happen. A merger was rumored... then

announced involving the UP, Western Pacific and the MoPac.

As reported in the

local papers in September, 1980, no lines on any of the three merging

railroads (Western Pacific, Union Pacific and the MoPac) were expected

to be abandoned as a result of the impending merger of the three rail

systems. Lincoln terminal operations were to be conslidated under a

joint facility agreement between M.P. and U.P. An additional U.P. zone

local train would operate to provide local freight service then handled

by MoPac in Lincoln. Except for routing improvements, there were to

be no major changes in operations in Nebraska outside of Omaha.

|

| MP

2023 - a

GP38-2 still a bluebird, but beginning

to show signs that it's being stripped of it's MP heritage. Lincoln,

Nebraska, 4/9/89 - Richard Wilson Photo/Todd Greuter Collection

|

When the merger

was announced, the MoPac was the larger system. The MoPac rails covered

more area than the Omaha based Union Pacific. MoPac owned more locomotives,

most of which were under 10-years old. It's fleet and operating facilities

were more modern using the cutting edge technology of the industry,

keeping with MoPac's philosophy. When the two systems were laid out

on a map, they met almost perfectly end-to-end, with little trackage

overlapping.

During the early

Eighties, the Missouri-Kansas-Texas line was seen running through Lincoln's

east campus neighborhoods over the Mopac. This was one of the first

signs of the impending merger going into effect, as the MKT exercised

it's new trackage rights, performing many of the operations the blue

MoPac Geeps had formerly done. After making a number of familiarization

trips over the "Siberian Subdivision", as the "Katy"

began calling it's new northern operations, the MKT took over and the

MoPac's presence began to disappear for the first time in memory. Service

to Lincoln slowed to semi-weekly, or even monthly at this time. By now

I was growing up and working for my dad. I missed witnessing the infrequent

action when it did happen behind our home. What a change it was to see

the Katy's green hues roll by where large Screaming Eagles once flew.

The daily 5pm MoPac freight out of Lincoln was a thing of the past.

Though they were still in use, the rails seemed almost forgotten. Still,

I had no idea what was about to happen next, even as I continued to

walk the rails and escape into my world.

|

Missouri

-Kansas-Texas # 632 is resting between assignments at Lincoln,

Nebraska, 9/24/89 - photo James Gilley collection

|

|

|

...the

sun sets upon the MoPac's Lincoln branch. Looking west to a local

MoPac landmark, the 48th St. Bridge and the former "Peck's

Grove" area.

|

Abandonment

Disaster happened

in 1984 when heavy flooding damaged the steel rails, totally washing

away a bridge crossing just west of the town of Weeping Water. The price

for repairs along the tracks would be high... very high for a 47-mile

long branchline.

There was a growing

lack of sufficient revenue from the the smaller towns to keep up with

the costs of modern railroading. The trucking industry was beginning

to bite into the profits that formerly belonged to only the line. And

the city of Lincoln had been pressuring the MoPac to build a new route,

one going around the city, and abandon the long used trackage - which

now found itself cutting straight through a busy, growing city that

seemed to have popped-up overnight from the once endless grain fields.

Perhaps the branchline was a victim of it's own success. There were

growing conflicts with traffic, including a tragic collision between

an outbound locomotive and a fire engine in 1981 that was in the headlines

for weeks.

Bob Soflin witnessed

these crashes from his own home. "Unfortunately, I also witnessed

two horrible incidents when the Eaglet was late one winter evening and

collided with a car at 66th before any signals were installed and there

were two fatalities."

"Again, I witnessed

the terrible accident with the Station 9 fire truck at Cotner &

Vine and the daily freight ... I can still see the fire truck spinning

like a top as the train came to a stop heading east on it's way to Union.

I knew one of the fireman that was killed, Harley Grasmic, as he was

thrown from the drivers seat and run over by the train. But, again those

are things that become imbedded in your mind and are apart of the railroad

heritage as, with anything else, human error and accidents will always

occur."

The merger with

the Union Pacific provided alternate access to Lincoln, the UP rails

ran well around the city. All of these ingedients had been brewing for

years under the surface, waiting for the right moment to combine for

the inevitable result. The railroad deemed to petition for abandonment

of the right-of-way between Weeping Water and Lincoln, just two years

short of the branch's 100th anniversary in favor of access to Lincoln

via the Union Pacific trackage. The towns of Wabash, Elmwood, Eagle,

and Walton which sprouted and prospered alongside the line had been

axed from the system. Weeping Water too, lost direct routes to Lincoln

and Omaha, but had kept busy enough moving cars to and from Union and

Louisville.

The last rail activity

I remember seeing from my backyard consisted of the strange sight of

a short string of yellow passenger cars, likely a UP inspection train.

There hadn't been any traffic on the rails for so long... and I wouldn't

see it again.

With a train of

three covered hoppers, MoPac GP15 #1668 made the final trip from Lincoln

to Elmwood and back on August 2, 1986. On May 13, 1988, scrapping of

the branch from Lincoln's 33rd Street all the way to Elmwood began.

In a just a matter

of a few years the Missouri Pacific Railroad, the blue engines with

their white eagles and war-paint on the nose, the friendly wave from

a bright red caboose, and ultimately the tracks themselves were all

gone. The right-of-way, which had once rumbled daily with passengers

filled with hopes and dreams, and supplies of grain, coal, lumber and

goods to nourish a small college town into a prosperous city, has been

preserved today as a very popular 30-mile long bike path... still puncuated

by the caws of bluejays in the shadey elm trees.

|

|

The

Missouri Pacific track rises then cuts through a hill west of 56th

St. in Lincoln in the 1970's. Back in 1886, this area was part of

the Thomson farm when, at 3:40 pm on August 14, the final spike

was driven, finishing the Lincoln segment witnessed by about 50

onlookers on horse-drawn carriages. Regular rail service would begin

on the 25th with almost an entire trainload of coal, followed two

hours later by the first passenger train, almost full without advance

publicity, headed for Weeping Water.

|

An

Update

After the UP/MP/WP

merger , Union Pacific took over the MoPac branchline from Lincoln to

the Falls City Sub at Union. With the bridge washout from the 1984 floods,

the UP opted to cut the west end of this line between Weeping Water

and Lincoln. That left the ex-MP track running only as far as 35th Street

in Lincoln for interchanging with the Omaha, Lincoln & Beatrice next

door to the fairgrounds.

|

A

paired set of former Missouri Pacific GP38-2's, now in U.P. paint,

change cars on old MoPac rails on a hazy Saturday afternoon, Lincoln,

Nebraska. Once a common site, now this too has

also passed into history with the final abandonment of the remaining

line by Union Pacific.

6/3/95 - T. Greuter photo |

The University of

Nebraska wanted the land the belonging to the line as it now cuts through

a portion of the campus. After years and years of pressure from the

University and City dating back to pre-merger days, the UP began pulling-up

these last rails in the Summer/Fall of 2000. Only track from the OL&B

interchange (18th Street) to Lincoln Lumber (23rd Street) remains with

segments yet to be removed between 27th & 33rd Street. It's was

assumed that the UP would interchange with the OL&B by trackage rights

to be secured over BNSF's Omaha Line between 9th Street and 17th Street,

but it's been observed that BNSF is handling the switching between the

two companies.

By mid-summer UP

the standard Geep pair assigned to Lincoln were called elsewhere as

the company ceased its switching crew operations in Lincoln.

Union is still an

important stopping point on the KC-Omaha mainline. Switching operations

continue along the remainder of the Branch to the limestone, concrete,

and fertilzer industries of Weeping Water and Louisville.

|

|

Pictured

is a MoPac locomotive that crashed through the wall of the Lincoln

depot into the ticket office in 1911.

Story courtesy of Jim McKee, Lincoln Journal-Star. Used with permission.

Click

on Article to read at Full-size

|

|