| Home | History | Route | Locomotives | Rolling Stock | Operations | Gallery | Bibliography |

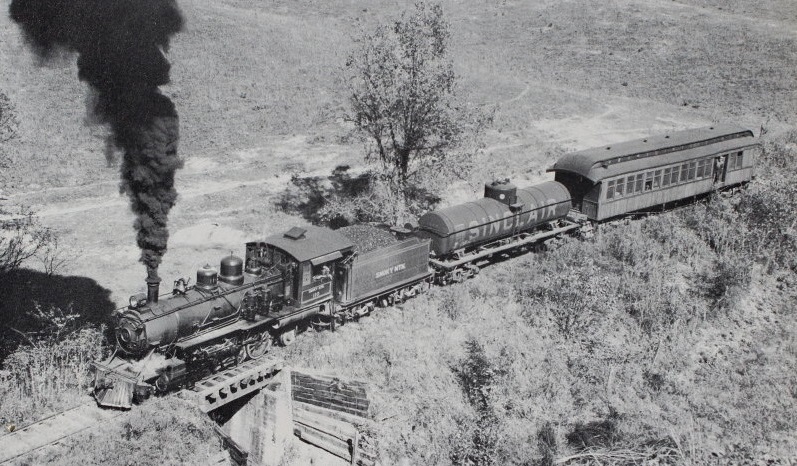

Smoky Mtn. RR Pacific #110 and mixed train halted while crossing Gists Creek in the late-1940s. Notice the Sinclair tank car is slightly derailed, and Conductor Linebarger is standing in the open door of combine car #102. (John Krause photo courtesy John Hewitt.)

The operating practices of the Smoky Mountain Railroad were usually interesting, often amusing, and like everything else connected with the railroad, born of necessity.

Originally envisioned as a property of some interest to a major railroad (i.e., the Southern), or possibly as a "bridge route" of sorts through the Great Smoky Mountains to connect with east coast lines, the Knoxville, Sevierville & Eastern Railway was probably never expected to function as an independent shortline railroad for a half-century! As a result, the railroad as built lacked certain amenities conducive to ease of operation.

Since the railroad was seldom profitable, and even when it was very little of the revenue was spent on maintenance (much less improvement), the daily operational techniques involved in just getting the trains over the line from Knoxville to Sevierville and back were remarkable.

In its early days, there was no turntable at either of the terminals of the railroad. Consequently, the locomotive on the westbound trains between Sevierville and Knoxville would run around the train, couple to the rear, and make the entire trip in reverse. To remedy this situation, an "Armstrong" turntable was installed at the Sevierville terminal. This allowed the locomotive to be turned in order that it might pull in a forward direction on the westbound run.

The human-powered "Armstrong" turntable at the Smoky Mtn. RR's Sevierville terminal. The "mainline" to the Little Pigeon River bridge and downtown is at upper right. (Trains Magazine photo.)This took care of the westbound trains, but what about the eastbound? Upon arrival at Knoxville, the engine would be pointed in the wrong direction for the eastbound trains, as the terminal rented from Southern Railway at Knoxville had no provision for turning locos. This problem was solved at "Crusher Wye," just outside of Vestal, and a couple of miles from the Knoxville terminal. The locomotive would cut loose from the train, negotiate the wye, and re-couple with the train, traveling on to Knoxville in reverse. Apparently, the crew had the procedure down pat, and would use the train brakes to keep the train rolling down the slight downgrade on the main while the engine was being turned on the wye, and the entire operation would be completed with only a momentary halt of the train to re-couple the locomotive.

Crusher Wye in South Knoxville, the former site of which is now included in Knox County's Charter E. Doyle Park. (U.S. Geological Survey)Now the locomotive was facing in the right direction for the return trip, but what about the train? To get into the Knoxville terminal required the negotiation of a series of switchbacks, before backing the train into the dead end yard lead. Apparently there was no "run-around" track, so the adept crew performed another interesting operation in order to place the engine on the head end for the eastbound train. The operation is known as a "flying switch."

The locomotive would pull the train up the Southern's K&A Branch, over which it had trackage rights from Vestal to downtown Knoxville, past the turnout to the Knoxville Belt and stop. When the switch was thrown, the train would be pushed downgrade onto the Belt and past the switch to the terminal lead. One crewman would man the switch, one the locomotive's front coupler, and the engineer the throttle. The locomotive next backed up the grade toward the K&A line, and when sufficient speed was attained, the train was cut loose "on the fly". Next, the loco would accelerate rapidly away from the train past the switch, which would then be lined for the terminal lead. The locomotive would then slow and stop as the train coasted into the terminal lead. Next, the locomotive would proceed back down the grade, back into the siding, couple and push the train into the depot in reverse. By all accounts, the crew performed this move flawlessly on a daily basis.

In its final years of operation, Ol' Smoky's crews adopted operating practices to ensure the preservation of their own lives, if not the equipment. One such practice that has become legend in these parts involved the crossing of Boyd's Creek trestle, the highest and longest trestle on the road.

The trestle was in such a weakened condition that the crew would stop the train before the trestle and cross on foot. One would stay behind to start the train at a snail's pace before jumping off, allowing the train to cross unmanned to the other side, where a crewman would jump on to stop the train. As soon as the remainder of the crew embarked, off would go the train to continue its journey.

Smoky Mtn. RR Pacific #110 crossing Boyds Creek trestle with Conductor Linebarger riding the pilot. This photo was from the late-1940s or early-1950s, probably before the crew began the safety practice described above. (Photo courtesy Mr. Dirk Chandler)Also in the latter years of the railroad, derailments were so commonplace that a "derailment car" accompanied the train on each trip. This ancient flatcar, loaded with wood blocks, crossties, picks, pry bars and other such essentials, was pushed ahead of the 44-tonner "just in case". Judging by stories of multiple derailments on single trips and days and days involved in moving a few carloads over the line, this practice was another that paid off.

Now and then, the "global reach" of this website really pays off. Fans and even casual observers e-mail us their nostalgic memories of the Smoky Mountain line, occasionally containing tidbits of detail concerning its operations. In the case of Lynn from Sevierville, however, we struck gold when his first e-mail arrived:

"The Smoky Mountain Railroad website brings back memories for me.

I worked as a bookkeeper for A.J. King Lumber Company from 1951 to 1961, less two years for military service. I recall the monthly rental checks for $500 which are referenced in your information. The train was a vital link between the hardwood flooring plant and its New York-area markets. This was the primary reason for Mr. King's interest in the line.

An interesting event occurred each time the train arrived from Knoxville. Prior to the involvement of Mr. King and his associates, near the lumber company a large warehouse had been built over the tracks. Large double doors had been installed in each end of the building. When the train was ready to leave the depot at the lower end of town, the station master would call our office. We would then send someone to open the doors so the train could pass through the warehouse on its way to our loading dock.

Your webmaster posing with the A.J. King Lumber Co. warehouse doors which straddled the Smoky Mtn. RR in east Sevierville. The opening of these doors for the trains' passage created the only "tunnel" on the Slow & Easy. (Photo by Mr. Jon Scott)Other times, when an empty boxcar was needed, we would send a bulldozer down the tracks through the heart of Sevierville to a siding at the depot. It was quite a sight to see a boxcar slowly traveling up Bruce Street behind a piece of earth-moving machinery.

These incidents, plus stories from family members who regularly rode the train during its early years, remain etched in my memory."

Sometimes valuable information reaches us via, shall we say, unlikely, circuitous routes. For example, Grady from Tennessee snail-mailed Bill from Vermont, who then snail-mailed us back in Tennessee (a round-trip distance of about 1,700 miles)! For simplicity's sake, we telephoned Grady direct (only 35 miles as the crow flies), who told us of his father's frequent livestock shipments via rail from Sevierville to customers all over Dixie. He said his father used to "throw a few biscuits in a sack" for the train crews to feed the world-traveling livestock.

How valuable are Grady's reminiscences? Practically priceless. We knew that the KS&E, K&C and probably the T&NC (Knoxville Division) had a few stock cars numbered in the 700-series. However, Grady's is the first account we have of their use. Since he loaded the animals at Sevierville terminal with his father, Grady's account was first-hand.

It seems everyone has a story of a favorite Smoky practice, usually passed down from fathers or grandfathers who were there or knew someone. Some are fiction...some are fact. As usual, fact is often stranger than fiction.

Text copyright © 1999 - 2018 Knoxville, Slow & Easy

| Home | History | Route | Locomotives | Rolling Stock | Operations | Gallery | Bibliography |