Adventurers in Utah for Spike

150

Promontory Summit -

150 years later

A Sesquicentennial

Chapter Two

Tooele Valley, Rio Tinto Kennecott Mine

Snow Covered Utah Mountain Ranges

May 3, 2019

Friday

by

Robin Bowers

Text and Photos by Author

The

author retains all rights. No reproductions are allowed

without the author's consent

Comments are appreciated at...yr.mmxx@gmail.com

After a restful night here in

Cedar City, UT and after loading the car, we drove to McDonald's

on W 200 N which was going through a remodel with only the drive

through open for business. After picking up our orders we then

drove a few blocks to the Union Pacific station where we ate

breakfast. I had my usual order of Egg McMuffin, hash browns

with a small coffee. Then it was time to hit the road. Leaving

town we connected with SR 130 northbound. At Minersville it was

then SR 21 north to Milford and then SR 257 going to Delta where

it was US 6 north to Lynndyl where north of here we had a Union

Pacific stack train backing with two crew members on the rear

platform. It was a cold ride for the crew.

Union Pacific 8377 north of Lynndyl. He would have to back all the

way to Lynndyl before he could set off the bad order car.

Looking south on US 6.

Union Pacific 5569 West near Jericho. We headed north to Mammoth

where we turned north onto SR 36.

On US 36 with Onaqui Mountains.

We just missed this northbound train near Vernon but caught up

with him at this grade crossing near Clover Valley.

Union Pacific 5673 East near Clover Valley.

From here we then drove into Tooele to our first destination of

the morning.

Tooele, UT

The scenic views from Tooele (pronounced too-ILL-uh) take in Great

Salt Lake to the north and across the Tooele Valley to the west -

the Stansbury Mountains.

Tooele Valley Railroad Museum

Locomotive 11 and 12 were

built as part of an order of 2-8-0's for the Buffalo and

Susquehanna Railroad by the American Locomotive Company at their

Brooks Locomotive Works in 1910. Bankruptcy caused the Buffalo

and Susquehanna to cancel the order, and ALCO kept the

locomotives until selling them. 11 and 12 where sent to the

Tooele Valley Railway in 1912. Locomotive 11 would be preserved

after retirement in 1963. 12 was scrapped in 1956, with the

tender being used to mount a snowplow. 11 would be the last

steam locomotive in Utah to be used in revenue freight service.

First displayed near the intersection of Vine Street and 200

West, 11 was moved to the Tooele Valley Railroad Museum in 1982

via rail. The museum also preserved the snowplow mounted to

locomotive 12's tender, several pieces of maintenance-of-way

equipment, and a pair of cabeese from the railway. Locomotive

100 and 104 were sold to new owners. A steam crane preserved at

the Nevada Southern Railroad Museum known as "The Crab" likely

originated at the Tooele Valley Railway or the smelter before

being acquired by the Wasatch Mountain Railroad (modern day

Heber Valley Railroad) before moving to its current location in

Nevada.

They were having a work cleanup party so we went through the

open gate into the museum's grounds.

Tooele Valley Railroad 2-8-0 11 is the star of the museum.

Snow plow.

Tooele Valley Railroad station with clean-up workers.

More volunteer workers, others were cutting and trimming the grass

and plants.

Track Speeder.

After our nice visit in Tooele we drove north on SR 36 to I-80

East to Exit 104 where we saw an interesting building across the

highway.

Saltair Pavilion, a Moorish palace theme.

Originally owned by the

Mormon Church, the original Saltair was intended to be a Utah

version of Coney Island, out on a boardwalk into the Great Salt

Lake. It was a nice escape for the people of Salt Lake City--

and a good way for younger Mormon couples to get out without

being chaperoned by their parents. It was partially owned by

groups associated with the Mormons, and they came under fire for

selling coffee, tea and booze (prohibited in the Mormon faith)

and for being open on Sundays (another no-no). The church sold

the resort in 1906, and when it burned down in 1925, a new

version was funded by new investors.

Scenes along the Great Salt Lake.

Union Pacific 5673 East at Smelter, UT. We drove down SR 111 south

to the Rio Tinto Visitor Center.

Mine tailings taken from the open pit.

We parked and walked to the Visitor Center where we purchased our

12:30pm bus tour ticket. The bus would shuttle us between the

parking area and the visitor's overlook in the world's largest

open pit copper mine. This has been on my bucket list for a long,

long time.

Bingham Canyon Copper Mine

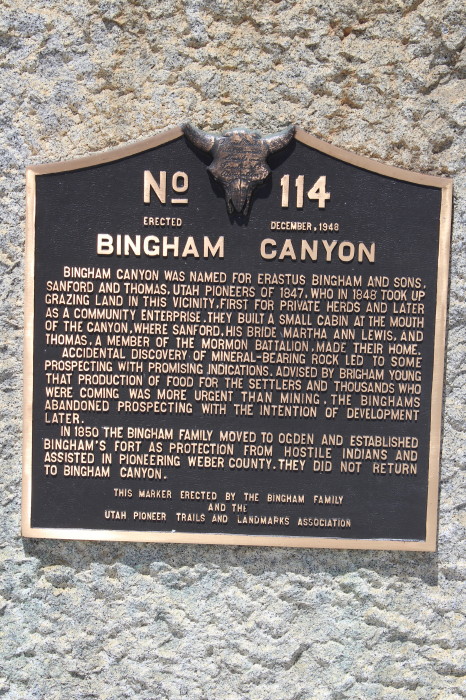

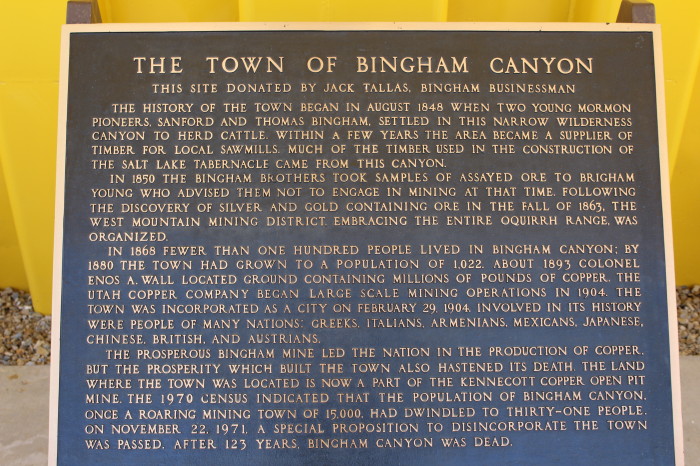

Bingham Canyon was a city

formerly located in southwestern Salt Lake County, Utah, United

States, in a narrow canyon on the eastern face of the Oquirrh

Mountains. The Bingham Canyon area boomed during the first years

of the twentieth century, as rich copper deposits in the canyon

began to be developed, and at its peak the city had

approximately 15,000 residents. The success of the local mines

eventually proved to be the town's undoing, however: by the

mid-twentieth century the huge open-pit Bingham Canyon Mine

began encroaching on the community, and by the late twentieth

century the Bingham town site had been devoured by the mine. No

trace of the former town remains today.

The geographic feature known as

Bingham Canyon received its name from the location's two first

settlers, the brothers Thomas and Sanford Bingham, who arrived

in the canyon in 1848. Initially, the area was utilized for

livestock grazing and logging, but the region's economic focus

changed with the 1863 discovery of rich gold and silver ore

bodies in the canyon. Mining activity in Bingham Canyon boomed

after the Bingham Canyon and Camp Floyd Rail Road completed a

line to the canyon in 1873, and as the region grew the focus

shifted to the high-quality copper ores in the district. As the

mines grew, the town of Bingham also expanded, spreading along

the narrow and steep canyon floor below the mines.

The Bingham Canyon mines

experienced their greatest boom during the first years of the

twentieth century, as the district's smaller mines were

consolidated under large corporate ownership. The most

significant development occurred in 1903, when Daniel C.

Jackling organized the Utah Copper Company to begin surface

mining at Bingham Canyon. The Utah Copper Company's mine

prospered, and this brought a tremendous influx of new residents

into the canyon. The town of Bingham Canyon was officially

incorporated on February 29, 1904. By the 1920s, the city of

Bingham Canyon was at its peak, with perhaps 15,000 inhabitants.

Urban development spread for some seven miles along the single,

narrow road winding up the steep canyon floor.

As with many western mining

towns, the Bingham Canyon area evolved into a collection of

diverse neighborhoods, many with pronounced ethnic affiliations.

Many Scandinavians lived in the Carr Fork area, while southern

and eastern Europeans congregated in Highland Boy, which was in

another branch canyon toward the top of the main city. As the

mainstreet in the bottom of the canyon grew, Copperfield became

the name of the upper section of the main town. Bingham itself

attracted British, French, Irish, Puerto Rican, Mexican, and

other immigrants and ethnicities. Numerous other small

neighborhoods and communities also existed. Most took the name

of the mine where they were located. Commercial, Boston Con, and

"the Niagara" were the first three communities to be mined away

or covered, as the last one was by Galena Gulch waste dumps.

Others were the Galena, Old Jordan, and Silver Shield (these

three found in Galena Gulch), along with Niagara. Telegraph was

in the upper part of the canyon, along with Copperfield, which

was threatened when the mining excavating was expanded and a

long one-way tunnel was built before 1940 to allow traffic to

reach the upper communities. Many names were colorful: Terrace

Heights, Dinkeyville, Jap Camp, and Greek camp were sections of

Copperfield. The Frisco, Yampa, Phoenix, and Apex were in Carr

Fork along with Highland Boy. Further down the canyon were

Markham, Freeman, and Frog Town (lower Bingham).

The size and importance of the

Bingham community began to fade as early as the 1920s. The

canyon's difficult geography made urban development difficult,

while exposing the town to the hazards of fire and avalanche.

The first effort to reduce settlement in the canyon came in

1926, when Utah Copper established the town of Copperton on the

flats east of the canyon mouth. This was a lovely community with

many copper products used in the building of the houses, and the

low rent encouraged company employees to live there. In 1956,

Kennecott sold the homes to employees for $4,800 to $6,000.

Increasing mechanization at the mine also reduced local

employment-and hence, Bingham Canyon's population.

By the 1930s it was becoming

apparent that the most significant threat to the town of Bingham

was the mine itself, whose ever-expanding open pit began

encroaching on lands formerly occupied by miners' neighborhoods.

The mine continued to eat away at Bingham throughout the middle

years of the twentieth century, and by 1971 little of the town

remained. That November, Bingham Canyon's 31 remaining residents

voted 11-2 to disincorporate the town, and the last buildings at

Bingham were razed in 1972. Today, most of the land once

occupied by Bingham has been consumed by the Bingham Canyon

Mine.

The Bingham Canyon Mine, more

commonly known as Kennecott Copper Mine among locals, is an

open-pit mining operation extracting a large porphyry copper

deposit southwest of Salt Lake City, Utah, in the Oquirrh

Mountains. The mine is the largest man-made excavation in the

world and is considered to have produced more copper than any

other mine in history - more than 19 million tons. The mine is

owned by Rio Tinto Group, a British-Australian multinational

corporation. The copper operations at Bingham Canyon Mine are

managed through Kennecott Utah Copper Corporation which operates

the mine, a concentrator plant, a smelter, and a refinery. The

mine has been in production since 1906, and has resulted in the

creation of a pit over 0.6 miles deep, 2.5 miles wide, and

covering 1,900 acres (3.0 sq mi). It was designated a National

Historic Landmark in 1966 under the name Bingham Canyon Open Pit

Copper Mine. The mine experienced a massive landslide in April

2013 and a smaller slide in September 2013.

The Wasatch Mountains and Salt Lake Valley. The building is the

smelter for the mine. The ore is moved on conveyor now days,

eliminating the rail ore cars.

At 12:20pm we boarded our bus and left on time. Our bus took us to

the upper viewpoint but some better views were from the lower

viewpoint to which you need to walk down to.

Haul truck tire display.

The lower view point.

Shovel dipper.

Locations of Rio Tinto west coast operations in United States.

Haul truck bed and Kennecott history display.

While we were visiting, two small earthquakes occurred but I

didn't feel any movement.

I took the shuttle back to

parking area and met up with Chris and we headed to Park City.

We took SR 111 to the Old Bingham Highway east to I-15 to I-215

to I-80 east to US 189 south to SR 248 into Park City and to

find our stop for the night.

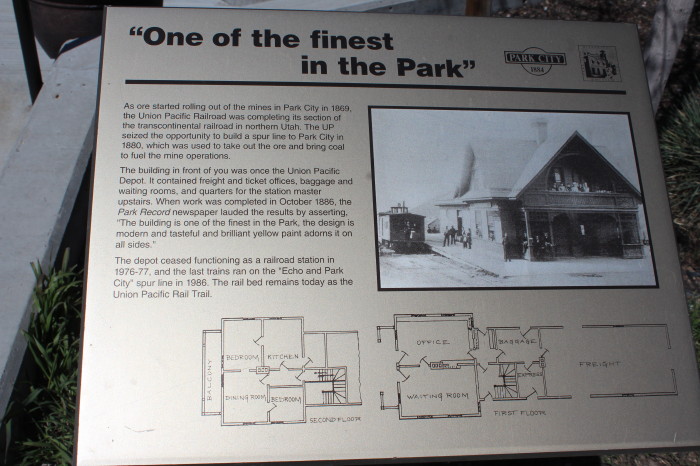

Park City Union Pacific Depot.

Street views of Park City.

Our first full day in "The

Beehive State" was going along swimming until we tried to find

our lodgings for the next two nights. Then it was one cluster

debacle after another. We arrived at the address Chris had from

the booking agent, but what we found was a nondescript

residential condominium building. We went inside and found no

front desk nor office and asked several people if this was a

hotel or motel. The answers ranged from "don't know" or "no." It

wasn't long before we realized something was amiss. After

several phone calls, we were told to go to another hotel on the

other side of town. As we had only been in town a few minutes

and with no local map for directions, we went into a local

business across the parking lot for help. Since they didn't know

the street we were looking for ether, a nice lady got on her

phone and was able to give us directions. We tried to follow her

instructions but got lost. The streets in Park City are laid out

in a labyrinth with short streets, dead ends and just for good

measure, a few obliques. After cruising up and down a few

streets, we finally found our destination.

After registering, picking up the keys, a

local map and parking permit, we drove to the proper place. It

turned out that our place was two blocks away from the first

place we stopped just on the other side of street. The parking

lot to our building was raised several steps or about a foot and

half from the ground floor of the building. As Chris was

unloading the car, he missed a step and took a tumble producing

a bloody scrape. Then as we were getting settled, we heard

pounding, sawing and drilling coming from the floor above. How

long was that racket going to last? Next we found out the

internet was not working. With that it was decided to go to

supper.

We had a name and address of a place but

couldn't find that either, with no help from several passersby.

We spotted a nice sandwich shop, Clockwork Cafe, and had our

diner there. The lone worker, a capable young man, was taking

orders, making the sandwiches, and bring them to the table.

After eating, Chris rushed back to the room but I decided stay

and soak in the ambiance of our stay in Park City. Going back to

the room I decided to walk the old railroad bed which is now a

hiking/bike trail. The trail ran behind our building but a small

stream ran parallel between the trail and the building so there

were only select places to cross over without getting wet. I

continued for several more blocks past our building and exited

on a paved street that I thought would return me back to the

motel. I was then turned around and missed my street by a couple

of streets. The city is not easy to navigate for strangers. But

I enjoyed exploring the streets and window-looking. After all, I

was out for a walk and sightseeing. Back in the room the

internet was working so I was able to check email before it was

time to turn in. Tomorrow we'll ride a train through a canyon.

Thanks

for reading.

Next Chapter - Riding the Heber

Valley Railroad

Text and Photos by Author

The

author retains all rights. No reproductions are allowed

without the author's consent.