| Home | Chapter History | National Info | Chapter Info | CINDERS Newsletter | Our FP7A | Transportation Links | Railfan Links |

|

The Philadelphia Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society Established in 1936

|

|||||||

Reading Company History

|

The Reading Company was originally created as the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, chartered in 1833. It was intended to haul anthracite from the hard coal region to Philadelphia via an alignment which followed the Schuylkill River valley. In order to have more direct access to coal needing transportation, the P&R was soon extended north to Mount Carbon, just outside Pottsville. Surveyed by the legendary Moncure Robinson, the P&R Main Line was built to run gently downhill for just over 90 miles. This was of tremendous value in bringing heavily-loaded coal trains to market while hauling the lighter empty trains back to the mines. Owing to financial difficulties, it did not offer an inaugural trip along the entire length of the railroad until 1842. |

|

From this modest beginning, the P&R would mature into a 1,400-mile system whose high traffic density would be the envy of many other railroads. A major theme of the early Reading was acquisition and consolidation with other lines of strategic value. After gaining control of numerous other lines radiating from Philadelphia, the P&R then faced the resulting difficulty of operating from three entirely separate Philadelphia passenger terminals. This was ultimately solved in the grandest possible style, with the construction of connecting lines that funnelled the passenger traffic towards one ultimate station: Reading Terminal, completed in 1893. The massive new Terminal's existence served as a daily reminder that there was more than one major railroad serving Philadelphia. This truth was felt most deeply just three blocks west, in the Pennsylvania Railroad's headquarters at Broad Street Station. While the relatively small P&R was a world apart from the enourmous PRR, it still took great pains never to let its #1 local competitor get the upper hand. |

| Unlike the PRR lines in the Philadelphia area, which rapidly separate upon leaving downtown, the physical character of the Reading's principal lines was of a "branch and trunk" nature. Extending north from Reading Terminal, the Ninth Street Branch was the four-tracked main artery for passenger trains in and out of the city. As one progressed north, secondary branches would diverge at intervals from this trunk. The trunk eventually contracts to a double-tracked line. Freight traffic begins to run alongside passenger tracks, then mixes with it at a few key locations. This made the blend of trains exciting to watch, but a headache for the dispatchers to keep organized. The railroad's main freight yard in Philadelphia was Port Richmond, on the Delaware River. This facility was the trans-shipment point at which the vast majority of the anthracite was loaded into coastal colliers as well as ocean-going ships. Signifigant iron ore and grain traffic was also handled here. Port Richmond was once the largest railroad tidewater freight facility in the world. Other P&R freight yards in the Philadelphia area were located at 5th St. & Erie Avenue, West Falls, Belmont, Abrams, Lansdale, 16th St. & Callowhill, and Nicetown. | |

| The Philadelphia & Reading also expanded across the Delaware River into southern New Jersey. In 1883 it bought the Atlantic City RR, which ran to that seaside point from Camden, NJ. After the purchase, P&R extended the line as far south as Cape May. Purchase of the ACRR served to heat up the grudge match with the PRR, whose own West Jersey & Seashore Railroad now faced serious competition. In the following decades, both railroads' seashore patronage went through a dramatic reversal of fortune. This culminated in the 1933 merger of the ACRR and the WJ&S. The resulting operation would be known as the Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines (PRSL). | |

| In 1901, the P&R gained a controlling interest in the Central Railroad of New Jersey (CNJ). This led to formalizing a previous arrangement which allowed the P&R to offer direct, one-seat passenger service from Reading Terminal to Jersey City, NJ. -- just a short ferry ride away from New York City. In turn, the Baltimore and Ohio RR (B&O) purchased its own controlling interest in the P&R by 1903. This arrangement was likewise useful to the B&O, who now had even more control over the arrangement which provided their own "seamless" passenger service between Washington D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Jersey City. After World War One, it became desirable for the P&R to simplify its corporate structure. The Reading Company, which had existed earlier as a holding company, became an operating company in 1923. Many previously-leased railroads which the Philadelphia & Reading RR had taken over - as well as the original P&R itself - were now providing service as the Reading Company. | |

|

During the late 1920s, the Reading Company examined the efficiency of its Philadelphia Division passenger services. The dense web of slow-to-accelerate steam trains was found to have room for improvement, but a solution was not going to be easy or cheap. The railroad decided that best way to increase overall track capacity while making the service more attractive (and profitable) was to electrify the lines. Between 1929 and 1933, the Reading constructed an overhead AC catenary system and purchased electric multiple-unit coaches. All Philadelphia Division passenger lines (except for the Newtown Branch) were upgraded. It was no accident that the Reading electrified its Philadelphia commuter lines at the same time that the Pennsylvania Railroad did so. Despite the costs, the advantages of electrifying a railroad with many frequent commuter trains were too major to ignore. |

|

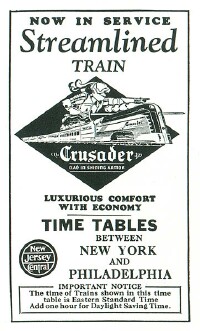

One of the highlights of Reading passenger service was the inauguration of its streamlined train which first ran in 1937 and was named the Crusader in 1938. However, after record-setting traffic peaks during World War Two, the Reading Company was slow to realize that it would not be included in postwar prosperity. Profits from both anthracite and carload freight were dropping. At the same time, passenger service was not only regressing from "less profitable" to "unprofitable," but was also becoming increasingly expensive to operate. This cut deeply into the shrinking profits from the railroad's traffic base. Even the 1952 systemwide retirement of passenger steam power in favor of new diesels was not enough to stop the cash drain. Non-electric passenger services, provided by coaches pulled by the new diesel locomotives, were replaced in turn by more efficient Rail Diesel Cars (RDCs) from the Budd Company in Northeast Philadelphia, one of its customers on the West Trenton Line. In 1962, the U.S. Postal Department announced that it would be withdrawing the contract for sorting mail aboard the Reading's Railway Post Office cars. This major loss of revenue guaranteed that the railroad's passenger service would remain deeply in the red. |

| Public transit agency SEPTA (and previous quasi-governmental organizations) provided subsidies to cover losses, but the Reading's costs were piling up faster than adequate relief could be provided. SEPTA took over daily operation of these trains (electric and diesel alike) in 1974, but did not assume full responsibility for them until 1983. | |

|

Another calamity was the surprise bankruptcy of newly-merged rail giant Penn Central in 1970. The failed PC was legally able to stop payments of monies owed to other railroads, while still demanding payment of debts owed to it prior to the bankruptcy. As a major partner in interchanging freight cars, this kept the Reading from collecting on debts that were needed for its own survival. By itself, this event was not enough to topple the Reading Company. But when combined with the permanent downturn of traditional rail freight business in the Northeastern U.S., plus ill-timed external labor problems which curtailed anthracite income, this was a battle that could not be won. The Reading Company declared bankruptcy in 1971. Unable to be reorganized on its own, it was included in the new Conrail system, which began operations in 1976. This was the end of the Reading Company as an independent, for-profit operating railroad. |

| Historical summary researched by and Copyright © Albert Alecknavage II. |

Direct website questions or comments to phillynrhs webmaster

Website created June 12, 2002

Last Updated July 6, 2003