|

BNSF and Predecessors |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

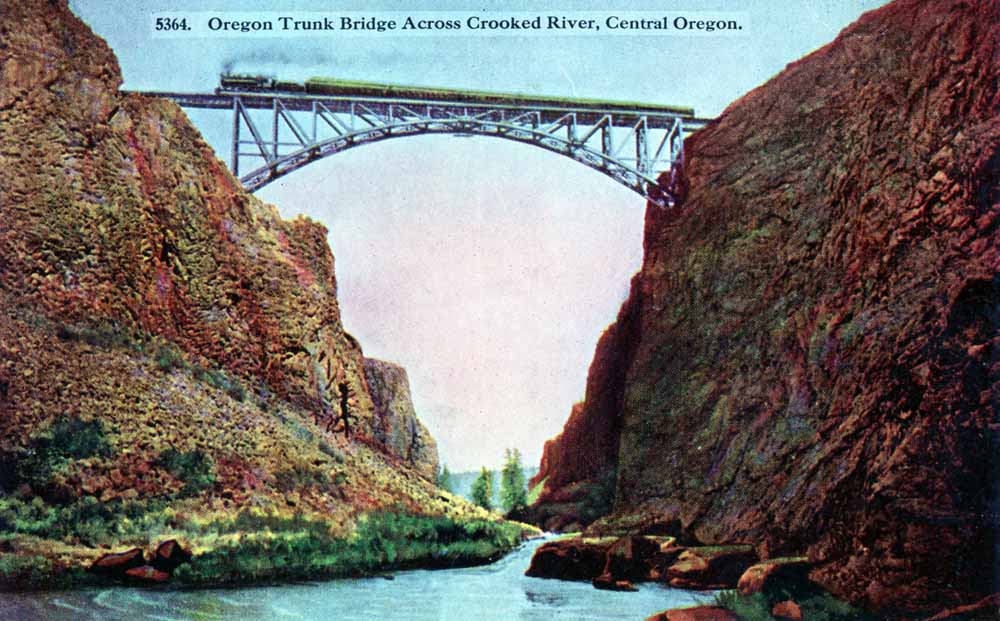

A southbound BNSF freight crossing the Crooked River on 17 March 2019. Matt C. Batryn-Rodriguez photo. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

Introduction Burlington Northern Santa Fe and its predecessor roads (Burlington Northern, Great Northern, Northern Pacific, and Spokane Portland & Seattle) crossed the border into eastern Oregon with two lines. The most important of the two is the mainline south into California, which sparked the last of the great western railroad wars. The second line crept into the far northeastern corner of the state. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

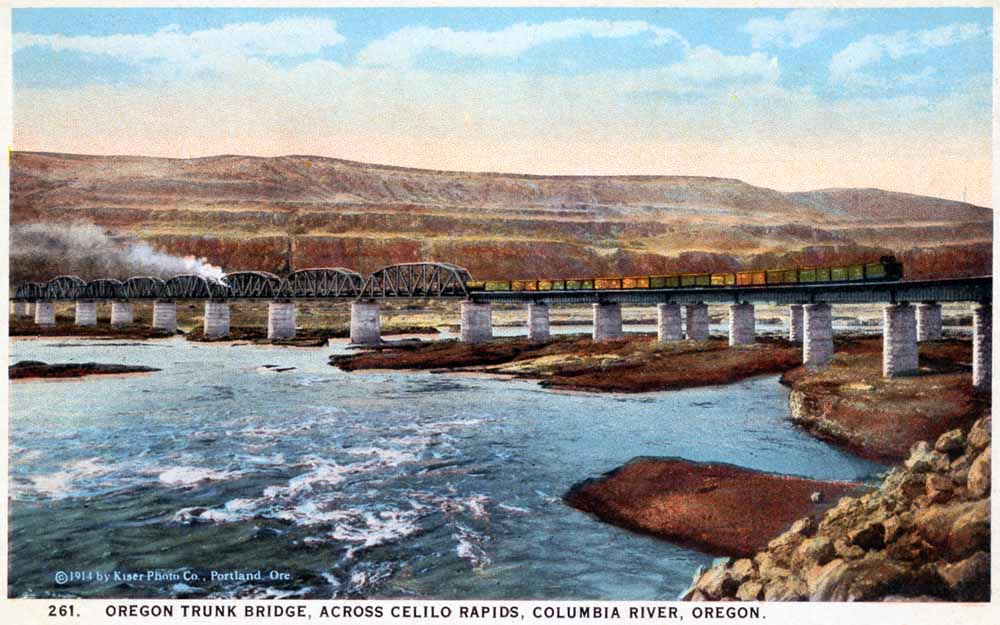

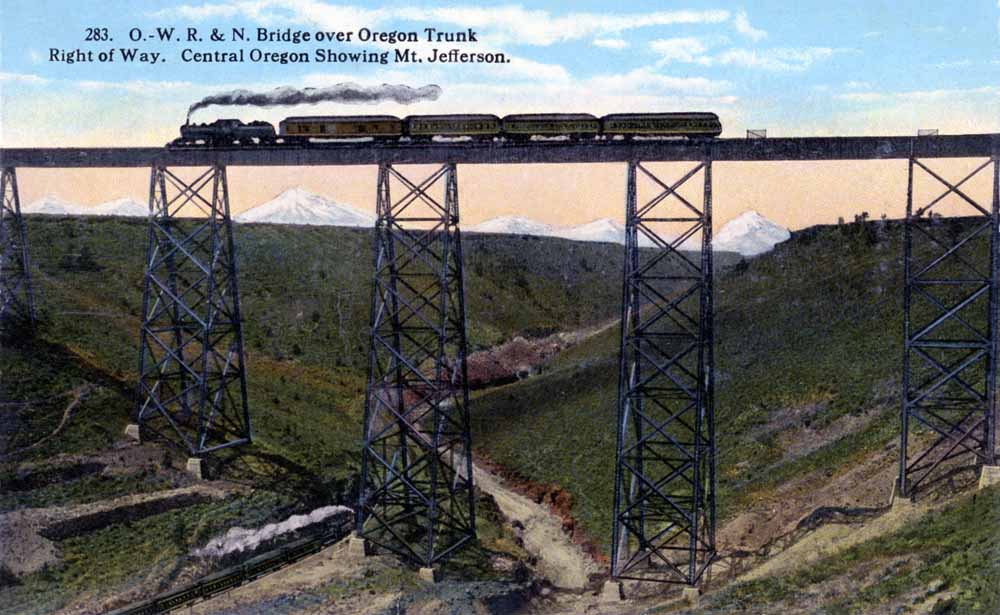

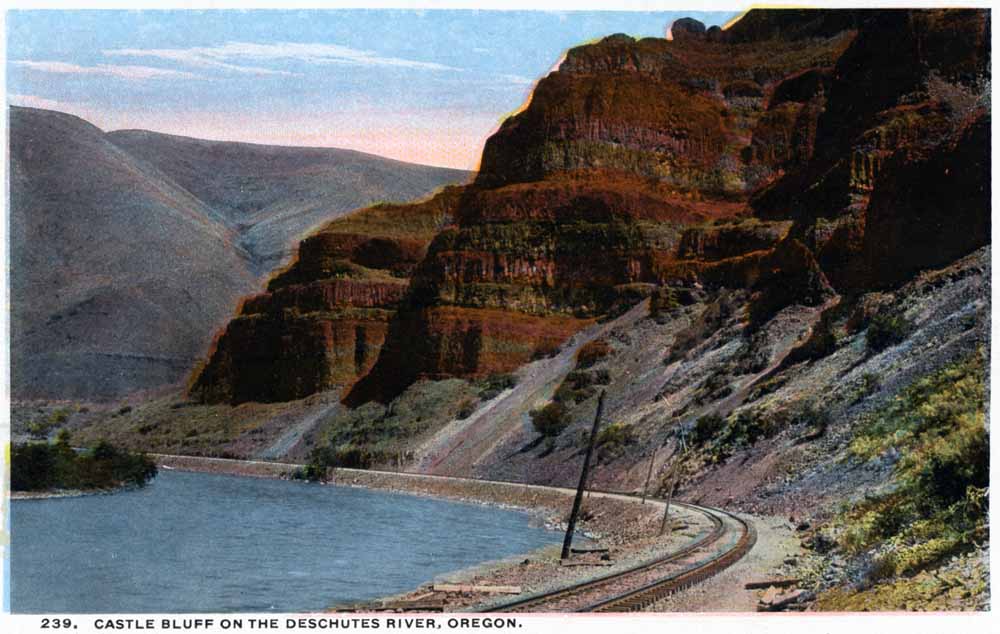

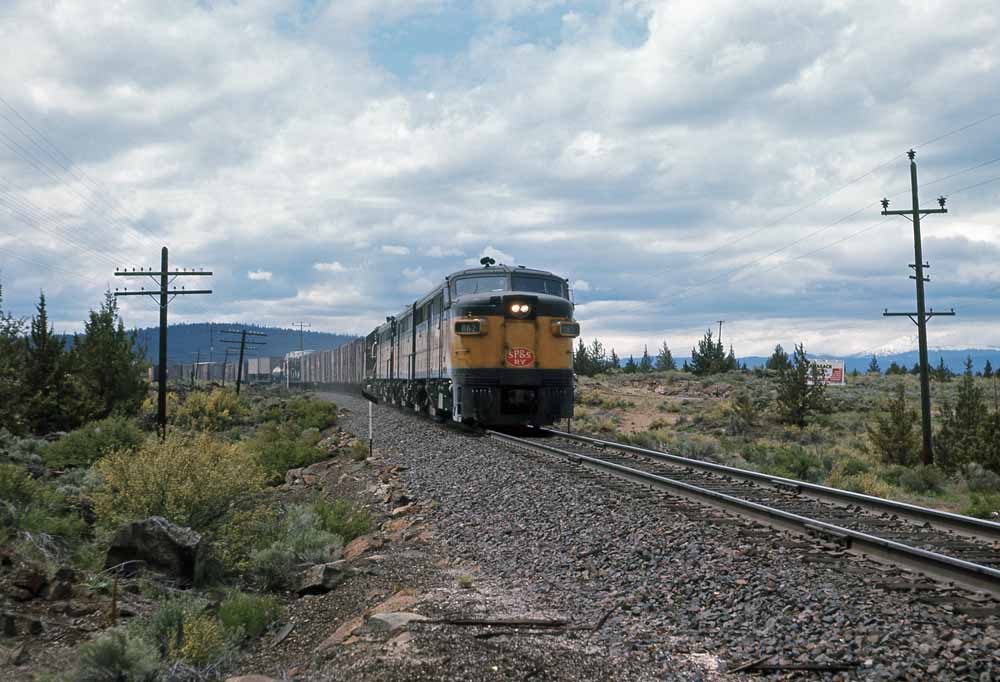

The Road to Bend- Oregon Trunk and Des Chutes Roads James J. Hill completed his Great Northern railroad west from Minnesota to Seattle in mid-1893. Once the transcontinental line had been completed Hill set out to expand his empire, acquiring control of the competing Northern Pacific a short while later. In the last years of the 1800s Hill exerted much influence trying to keep the newly independent Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company either independent or in a joint control situation between the GN, NP, and UP, but Edward Henry Harriman's rise to power over the UP thwarted those plans. In response, the GN and NP jointly formed the Spokane, Portland & Seattle, which completed a line from Spokane, WA, to Portland, OR, along the north bank of the Columbia River in March 1908. Hill's biggest dream had always been to extend his Great Northern south into California. However, California at the time belonged to Edward Henry Harriman, who controlled the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific railroads. Harriman was as determined to keep Hill out of California as Hill was to get into the state. Hill's first attempts to build to California went down the west side of the Cascades, where he found Harriman blocking his path at every turn. Hill then turned his gaze east of the Cascades. A U.S. War Department survey in 1855 found the Deschutes River canyon "utterly impracticable" as a potential railroad route. However, by 1900 engineering science had progressed enough that various parties started evaluating the canyon. In 1905 a group of Seattle businessmen started surveys for a railroad, which caused Harriman to take notice. Harriman responded to this development by incorporating the Des Chutes Railroad on 2 February 1906. This prompted the Seattle group to get organized, and on 24 February 1906 they incorporated the Oregon Trunk line. Both Oregon Trunk and Des Chutes filed maps with the General Land Office (GLO). The GLO rejected the maps of both railroads, asking them to re-survey their routes so that the proposed routes ran 100 feet above the water line so that dams could one day be built. This started a legal battle over maps, which would determine who had priority to build in places where the two surveys conflicted. The Des Chutes Railway did not have money problems, but the Oregon Trunk did. The OT eventually financed the legal battles by selling stock, some of which ended up in the hands of a contractor working for the SP&S. The contractor reported to Hill that the Deschutes Canyon would make a good railroad route. However, Hill took no immediate action.  Postcard view of the bridge the Oregon Trunk built across the Columbia River.  The Oregon Trunk and the Des Chutes railroads winding along the Deschutes River. In the summer of 1909 Hill sent his old friend John Stevens on a fishing trip up the Deschutes River canyon with instructions to look over the OT as he went. Stevens was a civil engineer and had surveyed much of the Great Northern route over the Rocky and Cascade ranges. Stevens gave a good report, and Hill started quietly funding the OT. The next step happened in July 1909 when both the OT and Des Chutes started building parallel railroads up opposite banks of the river. Hill's backing of the OT finally became public knowledge in August. The two railroads continued to build parallel lines, with a good amount of conflict along the way. Most of the fighting took place in courts, although both sides did whatever the could to slow the progress of the other on the ground. The Spokane, Portland & Seattle eventually purchased the OT outright. Harriman's death on 9 September 1909 caused the two sides to start working together. On 17 May 1909 the two sides signed an agreement ending the conflict. The agreement would see the two companies share twelve miles of track to avoid the Warm Springs Indian Reservation, with a second stretch of joint line extending from Metolius to Bend. James Hill himself drove the final spike completing the railroad in Bend on 6 September 1911, and regular service started on 30 September. The two railroads combined spent $25 million dollars to reach a town of less than 1,000 people.  Postcard view of the Oregon Trunk passing underneath the O-WR&N bridge at Madras.  Postcard view of Castle Bluffs along the Deschutes River.  Postcard view of the Oregon Trunk bridge over the Crooked River. Traffic over the new railroad did not really start to develop until the Brooks-Scanlon and Shevlin-Hixon sawmills opened. However, even with the new lumber traffic there was insufficient business to support two parallel railroads to the region. Two agreements, one in 1923 and the second in 1935, allowed for the abandonment of all duplicate trackage. The Oregon Trunk assumed all operational control and maintenance responsibilities for the line, even through UP retained ownership of a part of the line. UP continued operations into Bend on trackage rights over the line into the early 2000s when it finally reached a haulage agreement with BNSF for all traffic on the line.  The Oregon Trunk depot in Bend in 1912. The railroad constructed a similar structure in Redmond. Jeff Moore collection.  A later view of the Oregon Trunk depot in Redmond. Jeff Moore collection.  SP&S #366, typical of the road's branchline power, in Portland on 20 May 1948.  SP&S #358, maybe in Bend.  SP&S #862 leading a freight somewhere on the Oregon Trunk. C.G. Heimerdinger, Jr.  SP&S #90 and #62 sitting in front of the enginehouse in Bend. C.G. Heimerdinger, Jr.  SP&S #97 wearing an experimental paint scheme while switching in Bend. Jeff Moore collection. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

On to California James J. Hill died in 1916. The Northern Pacific became independent again, but it retained its half share of the SP&S. Even after Hill's death his company remained determined to get to California, and they finally were ready to move in the early 1920s largely thanks to the efforts of Arthur Curtis James, who at the time sat on the boards of the both the Great Northern and Western Pacific railroads and favored a joint north-south main line between the two carriers. However, a plan to use the existing Oregon Trunk to build south from Bend hit a snag when the Northern Pacific decided not to support the expansion. NP officials made several trips through the region south of Bend, usually accompanied by various local timber industry officials. These tours sparked wild speculation about a new NP line into central Oregon in the local media, but apparently the NP brass was not impressed with what they saw. GN decided to press on alone and filed an application with the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to build south from Bend to Klamath Falls, with the planned route running via Silver Lake and Sprague River. Southern Pacific had just completed their Cascade Line and did not like the idea of sharing traffic from the Klamath Basin with any other railroad, and they presented arguments against the GN application, claiming that to allow the construction would represent a wasteful duplication of facilities. The citizens of Klamath Falls rose up in support of the GN application, pointing to a need for competition in the basin. In the end the ICC agreed with both the SP and the citizens of Klamath Falls. The commission recognized the need for competition and granted GN permission to build the line, but then in the same decision they agreed with SP's argument by directing that road to provide GN with trackage rights over the newly completed Cascade line to avoid the wastefull duplication of facilities. At the same time the ICC also indicated it favored a joint GN-SP control arrangement of the Oregon, California & Eastern railroad, which the SP had just acquired. Neither of the big railroads were happy with the forced arrangement, but they finally came to an acceptable agreement in June 1927.  Great Northern #1350 in Klamath Falls on 9 April 1938.  Great Northern 2-8-2 #3113 in Klamath Falls.  Great Northern 2-8-2 #3120 switching in the Klamath Falls yard.  Representative of the larger steam power Great Northern typically assigned to the Klamath Division is the #3350, seen here in 1932.  GN #3116, seen here north of Bend on 4 April 1948. Osburn photo. In the meantime the GN struck south from Bend. The ICC originally set the northern end of the forced shared trackage at a point known as Paunina. A later agreement moved the junction point four miles south to the town of Chemult to avoid crossing Highway 97. To get to Chemult the GN line would lie directly adjacent to an already existing railroad for much of the distance, this being the logging railroad of the Shevlin-Hixon Lumber Company. To reduce initial costs and expedite construction GN purchased a 75% interest in the Shevlin-Hixon mainline from Bend south to La Pine. Shevlin-Hixon planned on logging the forests south of Bend for many years into the future, and the agreement with GN allowed the lumber company to continue running trains north to Bend. An additional 35 miles of new construction brought the GN into Chemult, completing the new line. The first GN trains entered Klamath Falls in 1928. GN did not pause long in Klamath Falls. By this point they had an agreement with the Western Pacific Railroad to connect their line with a new branch of the WP to be built northward from Keddie, CA. The two companies planned to meet at Lookout Junction, CA. At the time the SP provided the only real railroad connecting California and Oregon. The only real competition they had was the Union Pacific system, which ran Portland-Salt Lake City-Las Vegas-Los Angeles. That routing did not pose a serious threat to the SP. However, a suitable alternative could be created by combining the SP&S/OT/GN with the Western Pacific and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe. The Western Pacific ran out of construction money at Nubieber, several miles south of Lookout Junction, and the GN extended their line south to the new junction point. The GN and WP met at Nubieber in 1931.  GN #3101 at Lookout Junction, California. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Operations, 1931-Present GN built the line south expecting to become a major player in the north-south transportation scene. They also planned to run a section of their flagship Empire Builder passenger train service through to San Francisco, but the generally dull economic times in the early 1930s coupled with problems negotiating passenger transfer agreements with other railroads combined to end all plans. The OT continued to operate a mix train service on the line north of Bend until the creation of Amtrak in 1971. Likewise the hoped-for bridge traffic never developed either. A later study showed that SP handled 83% of the gross ton-miles moved over the Klamath Falls-Chemult joint trackage between 1930 and 1955. However, GN did handle a lot of lumber generated along the new line, especially from the huge Weyerhaeuser sawmill in Klamath Falls. Events on the line followed predictable industry trends through the years, with diesel-electric locomotives replacing steam power. A big change came in March 1970 when the Great Northern, Northern Pacific, and Spokane, Portland & Seattle merged to form Burlington Northern.  GN #598, one of two dynamic brake equipped SD-9s the company bought specifically to power that OC&E, switching at Klamath Falls. Jeff Moore collection.  SP&S #93 switching in Bend. C.G. Heimerdinger, Jr.  SP&S #334 and GN #706 sitting next to the Great Northern shop in Klamath Falls. C.G. Heimerdinger Jr.  SP&S #334 and #331 switching in Klamath Falls. C.G. Heimerdinger Jr.  BN #4256 in Klamath Falls on 24 May 1971. W.L. Hammond photo, Jeff Moore collection.  BN and Western Pacific cabooses in Klamath Falls on 29 March 1978.  BN's Klamath Falls shop building on 29 March 1978. The three railroads stepped up efforts to compete with the SP, with the result that traffic levels became healthy. However, this spirit of cooperation declined as the 1970s closed. The BN managed only two trains a day each way south of Bend through the 1980s and much of the 1990, with one of the trains terminating at Klamath Falls and the other running through to Nubieber. Traffic levels fell further after the Union Pacific purchased the Western Pacific in 1983. The line's days as a through route almost ended after a tunnel fire and collapse on the ex-Western Pacific portion of the line south of Nubieber. UP detoured their trains onto the SP main south of Klamath Falls, and for a while local interchange traffic was all BN had on their line south of Klamath Falls. UP decided to re-build the tunnel, which re-opened the route to through traffic. BN merged with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe to form Burlington Northern Santa Fe in 1995. Two years later Union Pacific completed its acquisition of Southern Pacific. The UP-SP merger came with some stipulations, one of which was that it had to sell the Nubieber-Keddie trackage to BNSF and provide BNSF with trackage rights on the ex-Western Pacific mainline from Keddie to Stockton. BNSF immediately set out to re-build and upgrade the entire length of the line. The company aimed to become a major player in the north-south transportation scene again, this time with great success. BNSF is now moving traffic over the old Oregon Trunk and the lines south from Bend at record levels.  Power from General Motors, Alco, and General Electric powering a Burlington Northern freight past Southern Pacific's Klamath Falls depot in the 1970s. Lee Hower photo.  A postcard featuring a Henry Brueckman photo of the Burlington Northern freight south of Klamath Falls in August 1973.  BN GP39-2 #2732 in Klamath Falls on 2 May 1981. Keith E. Ardinger photo.  In the late 1980s and early 1990s BN leased on occassion locomotives from the McCloud River Railroad to power its increasingly infrequent Klamath Falls to Bieber trains. MR SD38s #37 and #36 are seen here in Klamath Falls on 4 June 1990. Keith E. Ardinger photo.  Leased EMD #762 switching the sawmill in Bend. Jerry Lamper photo.  BN SD40-2 #3059 at Deschutes, just north of Bend, on 26 May 1995. Keith E. Ardinger photo.  BN #3550 leads a southbound freight into Oregon at OT Junction in 1996. Keith E. Ardinger photo.  BNSF #790 leads a train through Delinger, Oregon, south of Klamath Falls, on 22 July 1999. Keith E. Ardinger photo.  BN #4501 leads a southbound freight through Lava on 23 October 1999. John E. Shaw photo.  BNSF #6136 in Klamath Falls on 1 November 2002. John E. Shaw photo.  BNSF #7808 at Madras on 17 March 2019. Matt C. Batryn-Rodriguez photo.  Power for the local freight out of Bend at Madras on 23 June 2017. Matt C. Batryn-Rodriguez photo.  BNSF #7582 at Moody on 25 October 2020. Matt C. Batryn-Rodriguez photo.  Another shot of the BNSF #7582, this time at Oakbrook, on 25 October 2020. Matt C. Batryn-Rodriguez photo.  BNSF #7652 at Gateway on 23 June 2017. Matt C. Batryn-Rodriguez photo. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

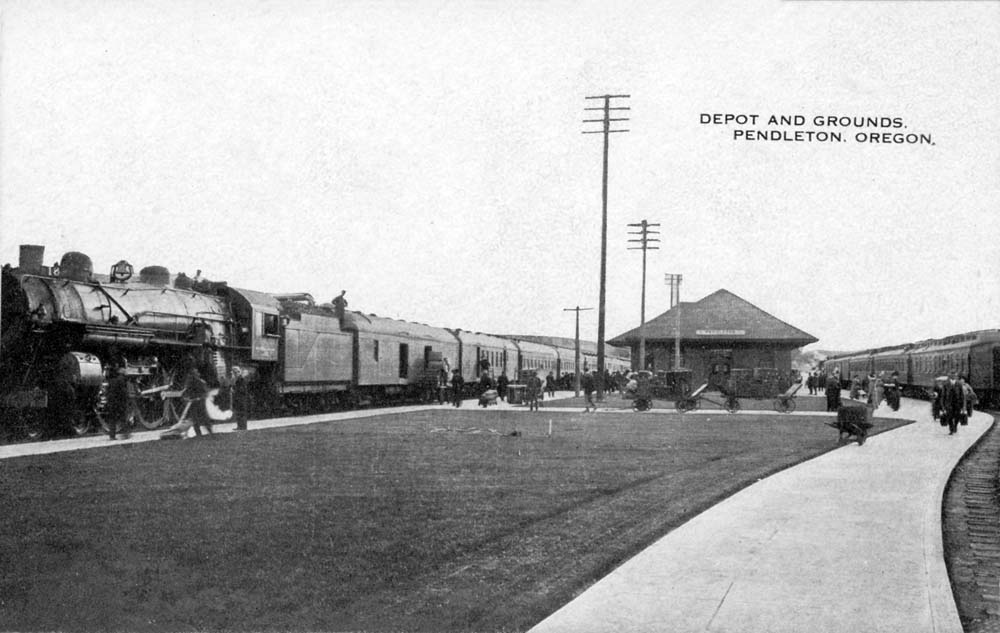

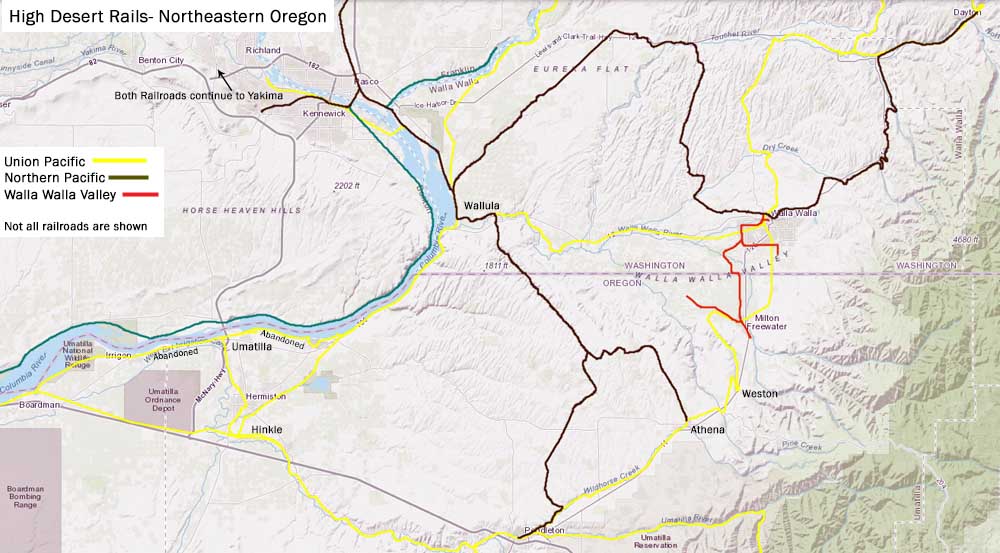

Pendleton Branch In the late 1870s, a battle started brewing in the productive agricultural lands of northeastern Oregon and southeastern Washington. The Northern Pacific mainline was rapidly approaching the region from the east, and the local Oregon Railway & Navigation Company was busy trying to protect its territory. In 1880, the two roads signed an agreement designed to ward off potential conflict by awarding the land north of the Snake River to the NP and the land south of the river to the OR&N; however, before the agreement could really take hold it was broken, which led to one of the most exteme examples of waseful duplication of rail lines ever seen. Demands by those individuals trapped in the service area of one railroad or the other for competition only intensified the problem. Umatilla County, Oregon, lay squarely in OR&N territory, which displeased a lot of citizens. Those living in the county agitated for Northern Pacific to build lines into the county, but at the time the NP was suffering financial problems and spending every spare penny on trying to push its mainline through to Puget Sound. In March 1886 a group of local citizens formed the Oregon & Washington Territory Railroad with the stated intentions of building a railroad line from Pendleton, OR, to a connection with the Northern Pacific at Wallula, WA. After an extensive period of organization and financing, work finally commenced in Wallula in late May 1887. George Hunt, the contractor hired to build the railroad, advanced the company most of the initial money, and to protect his investment he started buying out the interests of the O&WT investors, and by the end of 1887 Hunt owned the railroad outright. After gaining control, Hunt started seeking subsidies from the towns and farmers in the region. By the end of January 1888 the company completed twenty miles of line headed south towards Pendleton; however, the citizens of that town balked at Hunt's subsidy request, which caused Hunt to stop construction on that line. Instead, Hunt extended the road to Centerville (later Athena) and started building lines towards Walla Walla and other towns that met his subsidy requests. Hunt and Pendleton finally came to agreement by the dawn of 1889, and by late summer of that year the O&WT reached the outskirts of town. Hunt squelched promised litigation from Pendleton residents opposed to the arrival of his railroad by completing the line through town to his depot site on a Sunday, when courts that might have enjoined his efforts were closed. The lines to Pendleton and Athena would prove to be the only lines the O&WT built into Oregon. Over the next several years the railroad built a substantial network of branches in southeastern Washington, mostly parallel to existing lines built by the OR&N. In early 1889 Hunt did start laying plans to extend the Pendleton line southeast into the Grande Ronde valley, specifically to reach established communities like Elgin and Union that the OR&N left off their mainline when they built through the valley. The O&WT did complete several miles of grade in the vicinity of Union, but before any further construction could occur a management change within the Northern Pacific threatened the favorable grain rates Hunt based the entire O&WT venture on. Hunt immediately set out to extend the O&WT from Wallula west to the Port of Gray's Harbor, which irked the NP. Hunt did manage to get a railroad built between Gray's Harbor and Centralia before legal maneuvers by the NP finally ended Hunt's venture. The O&WT then attempted to sell itself to the NP, but the NP did not have the cash. The O&WT entered bankruptcy protection by the end of 1891. In August 1892 a group of local citizens, some of which had been involved with the O&WT, incorporated the Washington & Columbia River Railroad, which purchased the O&WT at forclosure. The W&CR started out with many of the same plans as the O&WT, but a poor economy quickly forced the new company into bankruptcy as well. An improving economy allowed the W&CR to emerge from bankruptcy in 1895, and in 1898 a company associated with the Northern Pacific finally purchased the W&CR. The W&CR remained an independent railroad until it was fully merged into the Northern Pacific in 1907. Northern Pacific and then Burlington Northern after the 1970 merger continued to operate almost all of the old O&WT/W&CR lines. Six day a week service over most lines lasted into at least the early 1980s. However, by the mid-1980s, competition from trucks and general declining farm economic conditions cut into the traffic base, and BN started dismantling the old O&WT/W&CR network. The Athena branch disappeared first; the Brogoitti Elevator Company at Duroc, only a few miles down the branch from the connection with the line to Pendleton, had been the only shipper remaining on the line, with the rest of the branch into Athena sitting largely un-used. The Interstate Commerce Commission authorized abandonment of the Athena line in March 1985. BN continued to operate the Pendleton line until 1992, when the company finally pulled out of all of its trackage beyond Wallula.  Union Pacific (left) and Northern Pacific (right) passenger trains at the joint depot in Pendleton. Jeff Moore collection.

|

|

Maps

|

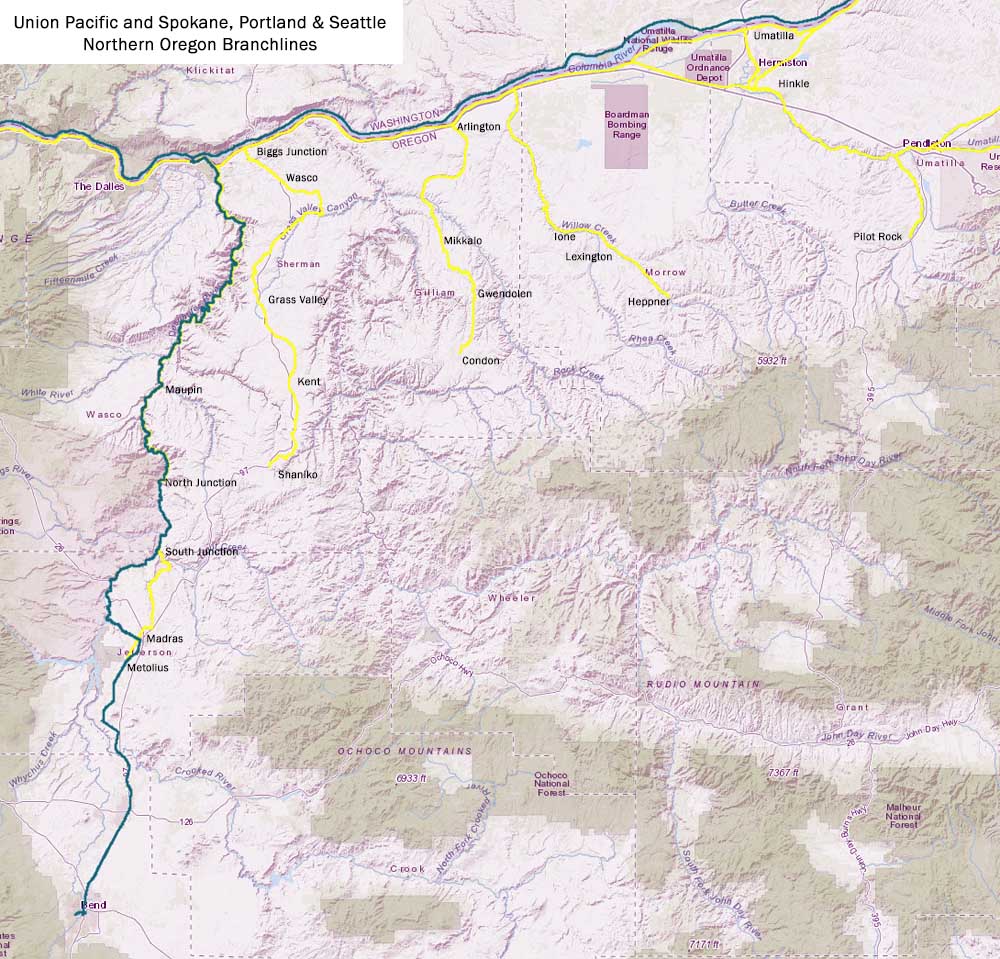

Oregon Trunk/Des Chutes Railroads

BNSF (SP&S/Oregon Trunk) is in aqua, Union Pacific is in yellow.

|

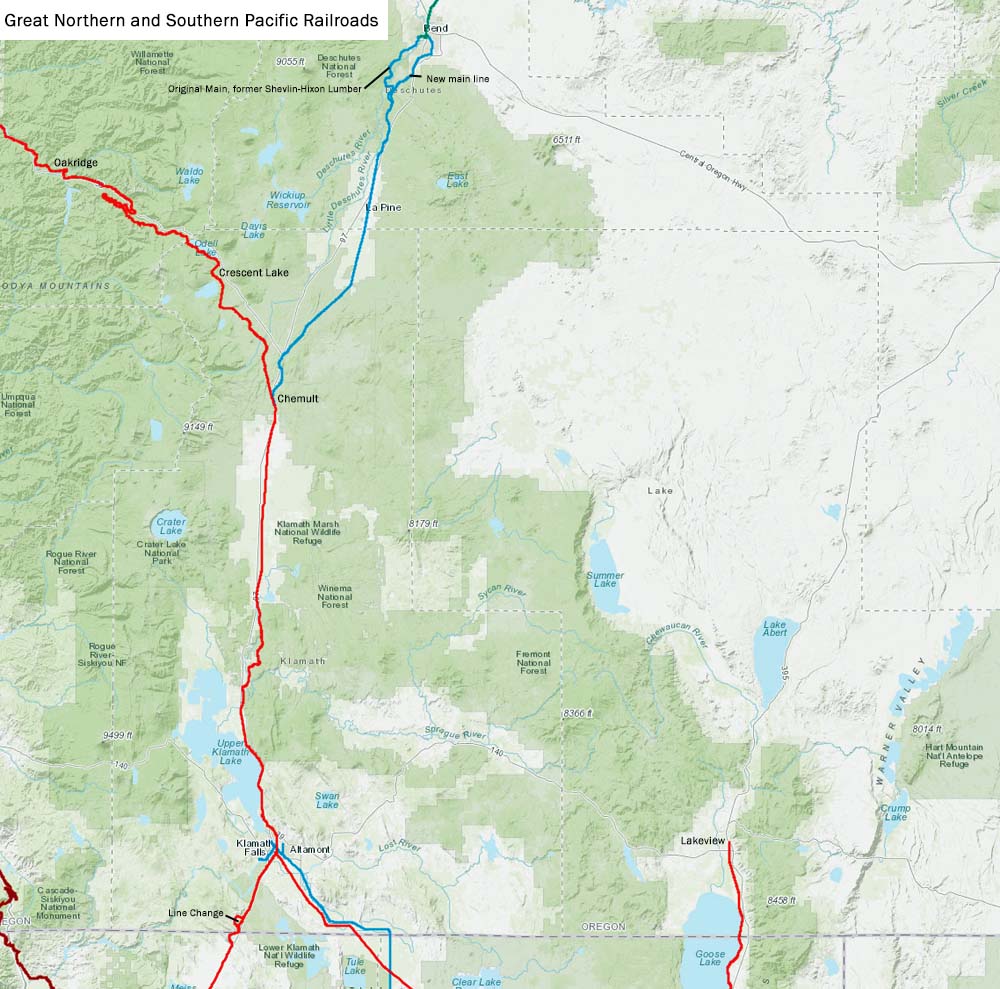

Great Northern and Southern Pacific

BNSF (Great Northern) lines are shown in blue, Southern Pacific is in Red.

|

Pendleton/Athena Branches

|

|

Photos of BNSF and its predecessors Bend in the 1970s Rob Jacox photos Lee Hower- Klamath Falls in October 1970 and March 1972

|

|

References Books "Across the Columbia Plain: Railroad Expansion in the Interior Northwest, 1885-1893". Peter J. Lewty, Washington State University Press, 1995. "Classic American Railroads" by Mike Schafer, MBI Publishing Company, 1996. "Encyclopedia of Western Railroad History, Volume III" by Donald Robertson, Caxton Printers, 1995. "Southern Pacific's Shasta Division" by John R. Signor, Signature Press, 2000. "Railroad Logging in the Klamath Country" by Jack Bowden, Oso Press, 2003. "Main Streets of the Northwest, Rails from the Rockies to the Pacific, Volume 1" by T.O. Repp, Trans-Anglo Books, 1989. "Railroads of the Columbia River Gorge" by D.C. Jesse Burkhardt, Arcadia, 2004. Periodicals "Oregon Trunk, First Section" by Greg Brown, July 2001 CTC Board: Pgs 18-27. "Oregon Trunk, Second Section" by Brian Rutherford, August 2001 CTC Board: Pgs 18-31. "Silver Salute for Burlington Northern", compilation article, March 1995 Pacific RailNews: Pgs 18-47.

|

|

More on the Web BNSF Corporate Homepage Rob Jacox's Western Rails page- some good shots of contemporary operations in the Bend area

|

|

|