While the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in Central California are referred to as "The Gold Country" and celebrated for that, the

most significant and valuable industry there, was that of logging and producing lumber. Second to nourishment, man needs shelter, and

all across the United States the forests and mills, the loggers and mill workers have given us comfort.

The Michigan-California Lumber Company, a successor to other companies, did its part. I was a part of the summer labor force from 1935 to 1941,

and had also spent other summers in the camp while I was younger. There are other stories of this company so I won't elaborate much on the

geography. The general location in California was east of Georgetown and northeast of Placerville. The logging was done at an elevation of

around 5000 feet in an area south of the Rubicon River, north of Big Silver Creek, and west of the Riverton-Wentworth Springs Road. Logs were

transported westerly to Pino Grande, the sawmill, for some 15 to 20 miles and cut into rough lumber.

Cut lumber traveled from Pino, maybe 10 or 12 miles, to the edge of the South Fork of the American River where if was ferried across on a

cableway where another train took it to Camino, the headquarters of the company, with drying and storage yards and a finishing mill. Lumber

was shipped from Camino in box cars on the wide gauge railway, the Camino, Placerville & Lake Tahoe Railroad, owned by the company, to Placerville

where the cars were handed over to the Southern Pacific Railroad. As I understand it, initiating the shipment grants that railroad a higher share

of the tariff, so rather than have S.P. build a line to Camino, the Company one-upped them. As to the cable across the river, this was an engineering

marvel, unique in the logging industry and a thrill to ride across on the half mile trip 1200 feet above the river.

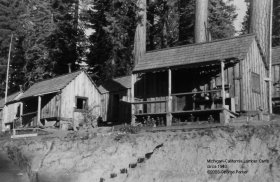

The logging camp was mostly portable and was moved every 3 or 4 years to be nearer the timber. The cabins, somewhere around 15 by 10 feet were

build on runners and could be skidded onto logging cars for transportation. They had a sliding window on each end and a door on the front. Cabins

for the men were unlined, but those for families were usually finished in knotty-pine. Occupants were free to add conveniences, such as a porch or an

awning, from a free supply of lumber. The cabins contained a wood stove and 3 or 4 metal cots and mattress pads. Occupants brought their own bedding.

Families usually had 2 cabins, and, as many of them came up year after year, had they conveniently furnished. I and my sisters and friends lived and

ate in my father's quarters. He was the 1-man office, timekeeper, storekeeper, medic, and friend of everyone.

There were a few permanent buildings in a camp, left there when the camp moved. The most important was the cook house, large enough to feed some 100

men on long tables, family style. Cooking and baking was on a wood range and water for dish-washing might have been heated through pipes in the stove, or

by a separate boiler, I don't recall. This is a good time to point out that there was no electricity in the camp. The only refrigeration was an insulated

building (portable) that was cooled by a gasoline compressor. Lighting was by kerosene lamps and Coleman gasoline lanterns. Radios were few, for batteries

didn't last long in those days, and one didn't want to run an auto radio long, as there was no way to recharge a dead battery.

The cookhouse was manned by "The Cook", a "2nd cook" (may we call him the "sous chef"?), a baker and 2 or 3 "flunkies". A principal feature of the

cookhouse was the "gong". This heavy iron bar, bent into a triangle, hung from an eave near the door. A musically talented flunky at 6:00 A. M. on week

days would waken the camp by rotating a metal bar around the three sides of the bar in rhythmic fashion that, after the first alarming sounds, actually

sounded pretty. A shorter tune was played at 6:30 announcing breakfast. Loggers would rush in, eat a plentiful breakfast, prepare a lunch to take with them,

and then head out to the track to board the train for their work site. I rarely ate in the cookhouse, but never heard any complaints. Dinner was interesting to

watch. The loggers would crowd around the door waiting for the gong, and rush in. Some time later, they would slowly meander out, fully sated, looking

relaxed and with a toothpick sticking out of their mouths. Whenever I see a toothpick I am reminded of that sight.

The other main building, later left at the site, was the blacksmith shop. With a dirt floor, a scattered supply of all shapes and sorts of metal, and

the forge, the usual cabin wouldn't do. Another central feature was the wooden water tank. While this would later be disassembled, it did not normally go

along at the time of a move. The location of this tank was important, for it had to be by the railroad track so engines could replenish, but also had to supply

water by gravity to the area of the cabins and to the cookhouse. Water was supplied to the tank by a pipe-line from a creek or a spring, sometimes at quite a

distance.

A feature of the camp for everyone was the common shower house. It was the usual cabin fitted with several stalls, the drain water flowing through slits in the

floor to the ground below and down the hill. In front was a deck where laundry could be done using 5 gallon cans and plungers. The "bull cook" would heat

up the boiler about 2:00 o'clock in the afternoon and the ladies and small children would bathe, and perhaps do laundry after. Men would rush in before dinner,

and perhaps, later in the evening, do their laundry. Occasionally, Pete Boromini, the veteran engineer of the 9 spot, would bring his engine close by, attach a

steam pipe from the locomotive to a box he had contrived. In a few minutes any greasy or pitch-laden jeans would be squeaky-clean.

The commissary was the center of communication and activity. The cabin was divided by one-third as an office and the rest as a store. Pipe tobacco, cigarettes,

snuff, candy and gum were big sellers. There was a limited amount of denim jeans and shirts, gloves, and shoes. For those who wanted to put hob-nails or calks

in the boots or shoes, they were available, along with the cobbler's "last" stored on the porch outside. Also on the porch was the alphabetized mailbox, supplied

by the evening train from Pino Grande. The porch, too, was the site for pay day, when the paymaster from Camino arrived twice a month with cash. There were

2 phones in the camp; 1 in the commissary and 1 in the camp boss's cabin. The line went only to 2 places; the office at Pino Grande and to the Forest Service

Fire Lookout in the area.

Another cabin was the "saw filers' shack". Remember, this was all before the days of chain saws. Fallers (the word "feller" was never heard of in the

woods) used 2-man saws, perhaps 10 feet long, and buckers 1-man saws of similar length. Saws would be brought in each night and traded for a sharpened

one. I have often thought there were two men doing the filing, but now that seems like overkill.

A pigpen was built for disposal of garbage. It was a daily function of the bull-cook to load the cans on a push cart and feed the animals. At the end of

the season the pigs would be slaughtered and used to feed the men. Paper and cardboard were probably burned, but tin cans, and there were lots of

them, were deposited in a dump. Their resting place, if located, might give a clue to the site of a camp.

While there was an auto road into most of the camps, by late summer they were usually in bad shape. Most of the roads from Placerville and from

Georgetown were dirt. Creeks were forded, and knowledgeable drivers knew enough to go through slowly. It's no fun pushing a stalled car out when the

engine wiring got wet. Most of the loggers came into camp in the spring (logging started after the snow melt) and stayed 'til closing, usually in October.

We younger ones often went out on weekends, though, for example, it took 3 hours to get to Sacramento. But we had such good social life in the camp

that we usually preferred to stay. We had family members and friends coming and going and they thought of the camp as a "resort".

Friday was always an awaited day, not just because it was the end of the week, but that was when provisions would be brought in on the train. Meat

was delivered by a local rancher (Bachi?), but all other food came by train. My father would phone the cookhouse and family orders to the Pino Grande

office about on Tuesday. They would phone it to Camino, and someone there would assemble it from Placerville and Sacramento. Families could also buy

bakery goods and meat from the cookhouse on a daily basis.

This is pretty much a description of the layout and the facilities. I have a few photos to post. If anyone would like to contribute, please do. I don't

how the Sierra Pacific Industries (Michigan-Cal's successor) operates, but we didn't cut anything under 30 inches, so that 30 or 40 years later there could

be another harvest. Swift Berry, the General Manager, was a graduate of the Biltmore School of Forestry, and his 2 sons, Jack and Bill, U.C Berkeley

graduates, served as foresters for the company at various times. These guys were point men for fun in the camps and taught us lots of baudy songs. Swift

later became a president of a bank in Placerville, and also a State Senator. I feel good about the way the company operated in those days, and thankful

for the summer employment they gave me. Pino Grande and the camp sites have disappeared. Some of the railway right-of-ways might be located, but the forest

has reclaimed most. If you like these stories, I'll write some more, but as I have said, after 70 years, I may have forgotten a little of the truth.