|

||

|

ERIE

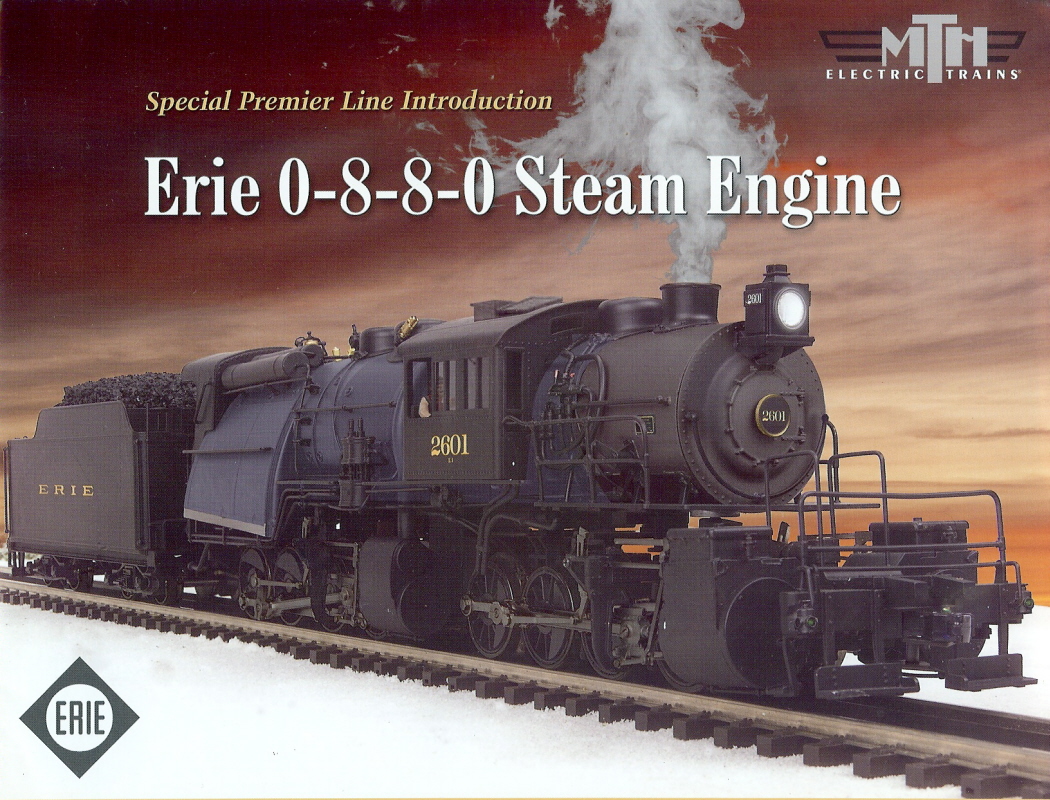

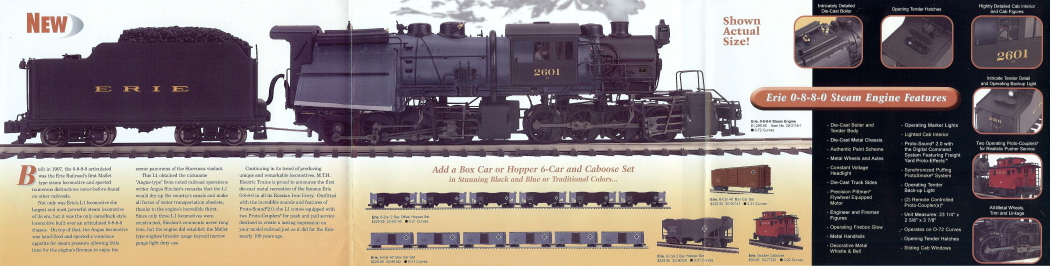

RAILROAD L1 Class - 0-8-8-0 Articulated

American Locomotive

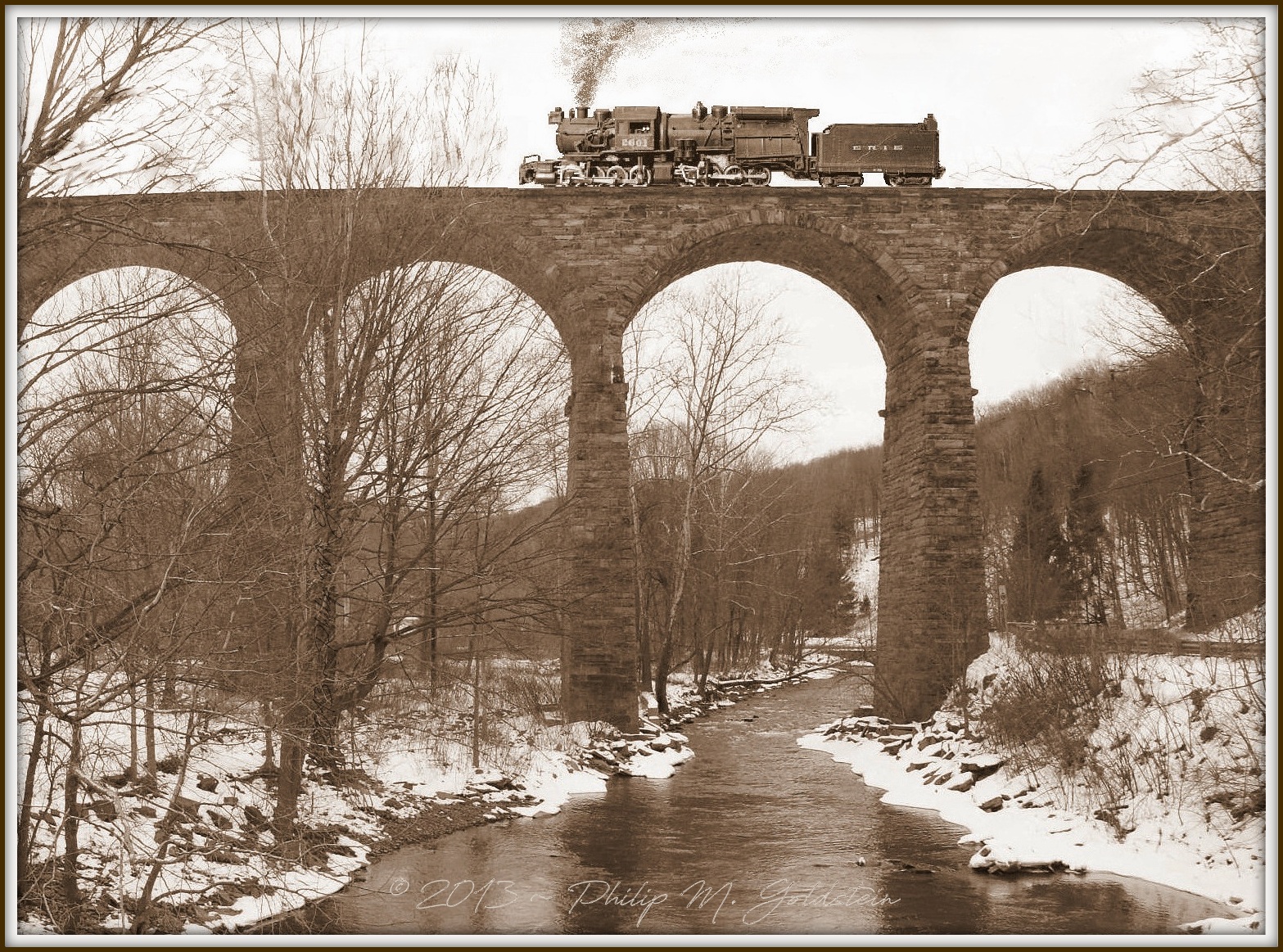

Works by Philip M. Goldstein |

|

|

ErieL1.info |

||

| 20 November 2024: |

Chapters added |

"They

were too big - |

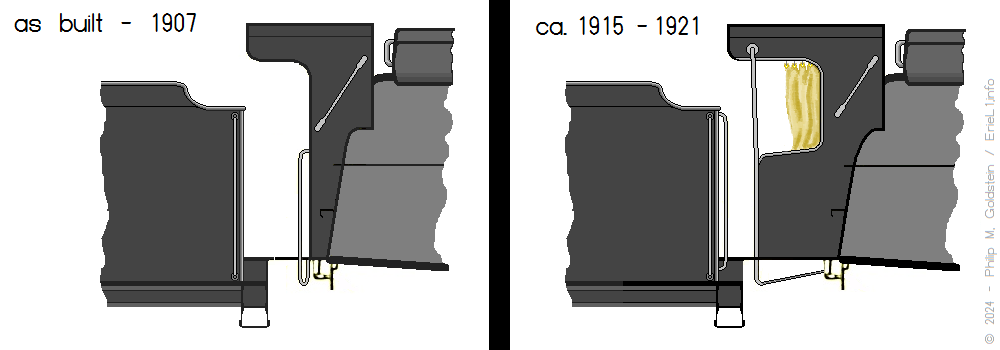

| 12 November 2024: | Firemans Canopy / Shelter profile changed ca. 1915 | Modifications

& Differences |

| 31 October 2024: | Mallet Compounding and Articulated chapters, w/ drawings added | What

is Compounding? Why the need for Articulation? |

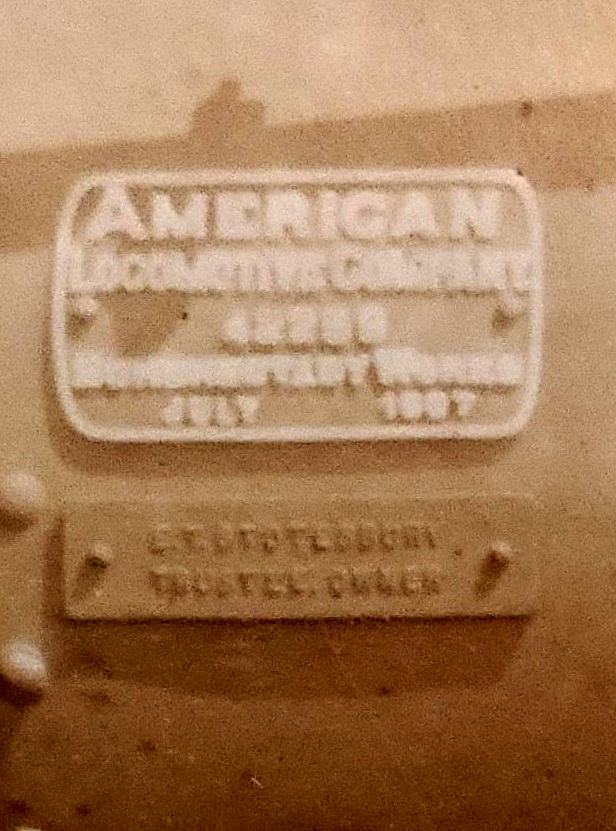

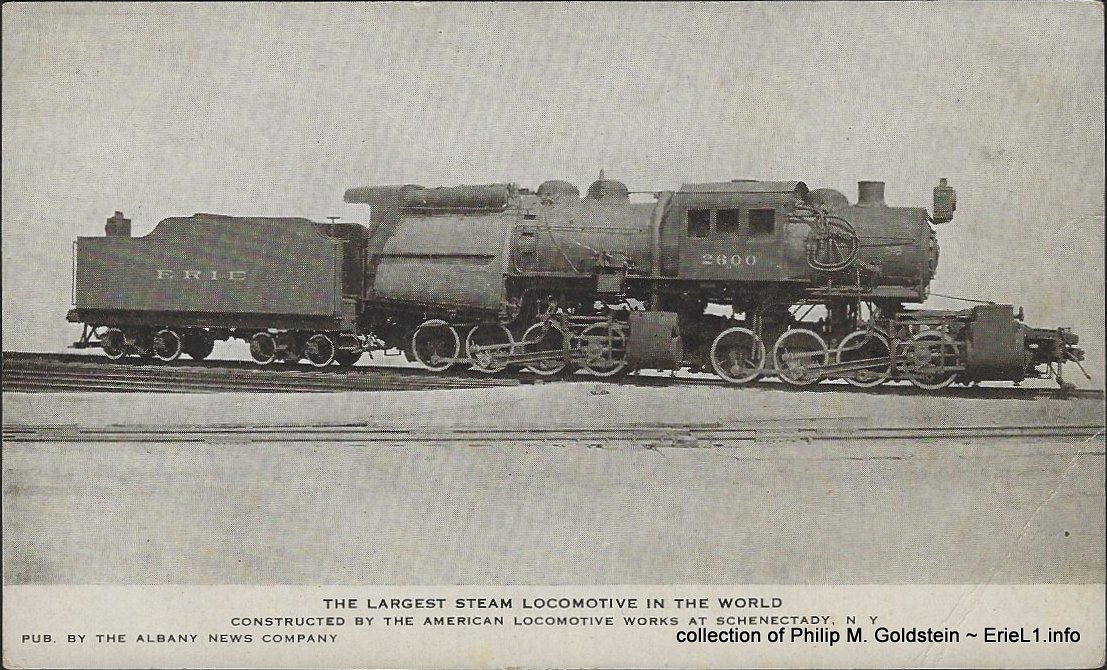

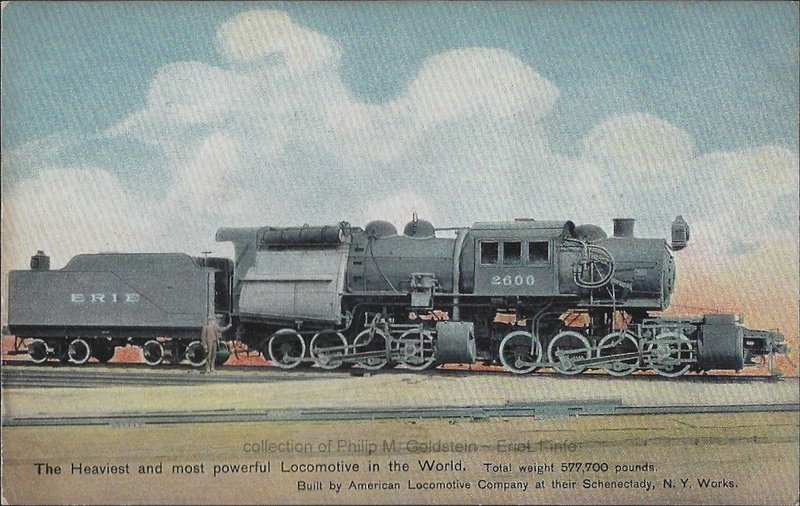

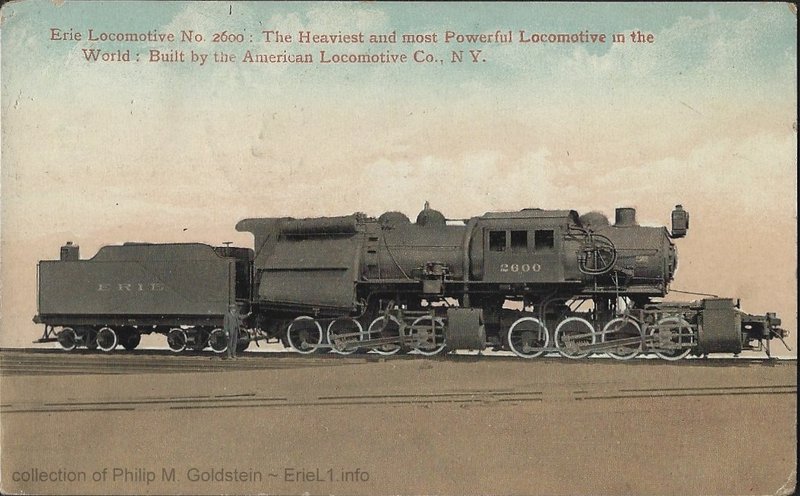

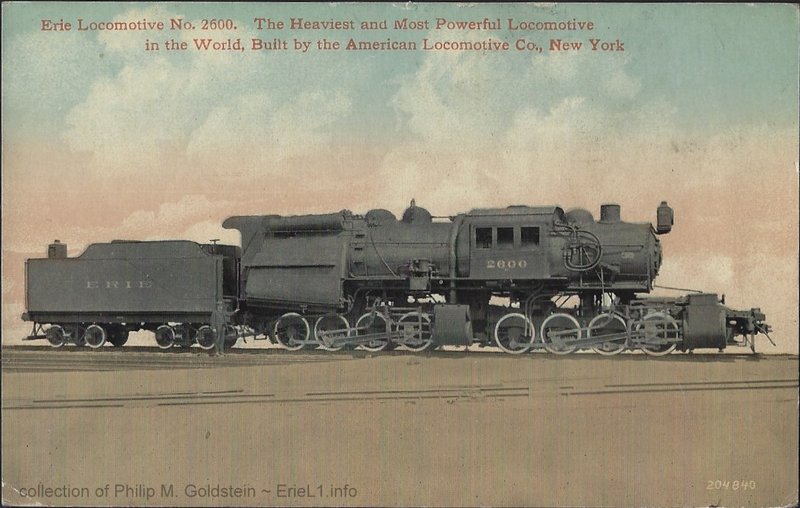

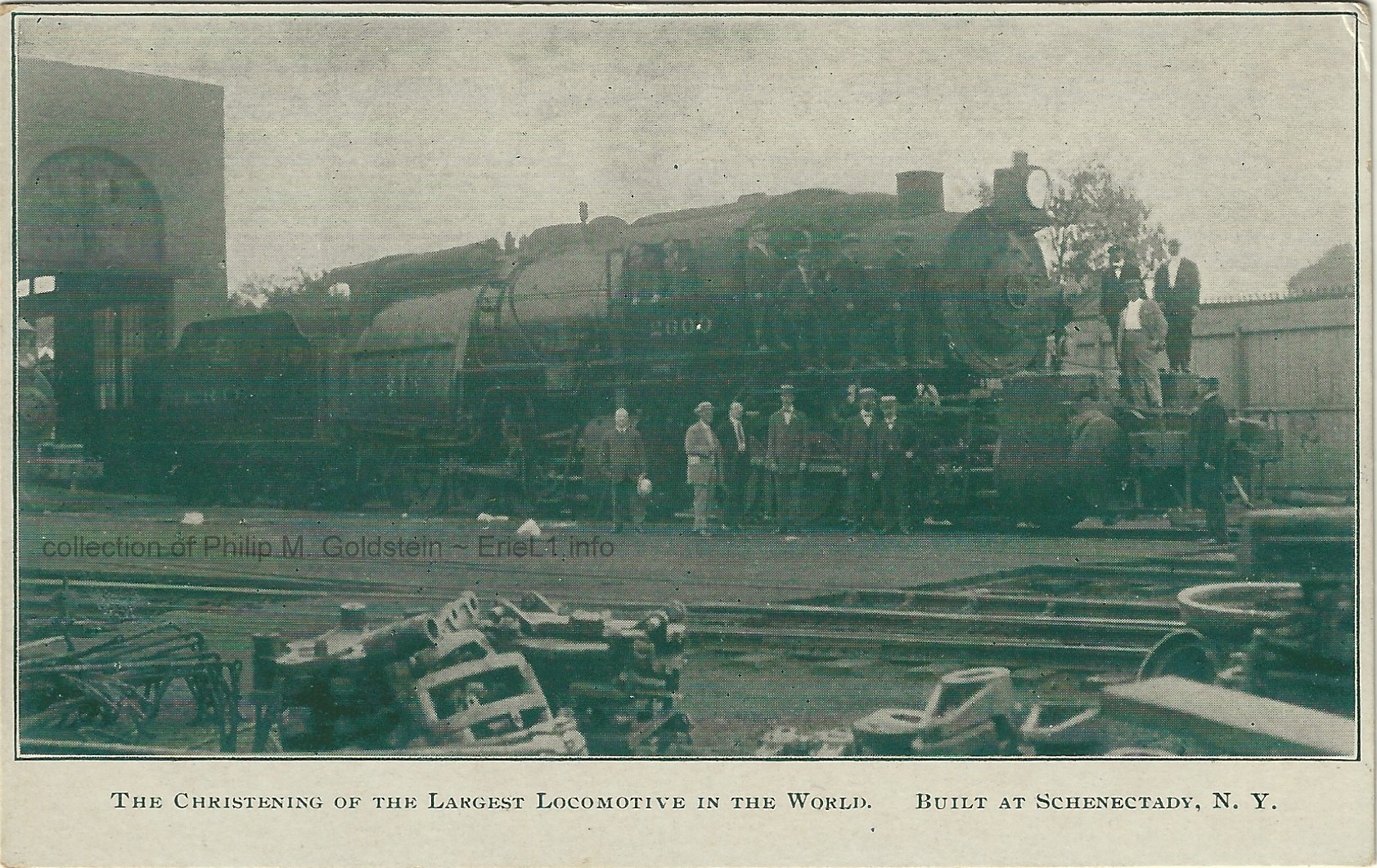

| 25 October 2024: | 2600 Christening at ALCo print added | Memorabilia & Photographs |

| 16 August 2024: | 2600 Christening at ALCo postcard added | Memorabilia & Photographs |

.

.

Click on the builders plate ![]() at the bottom of each chapter

to bring you back to this table of contents.

at the bottom of each chapter

to bring you back to this table of contents.

.

.

.

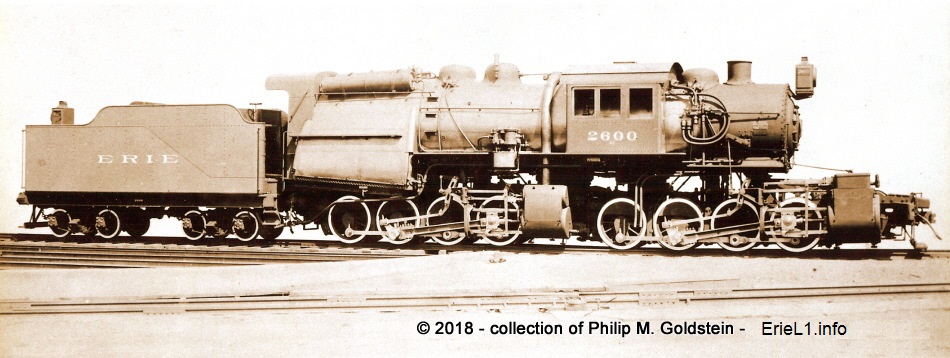

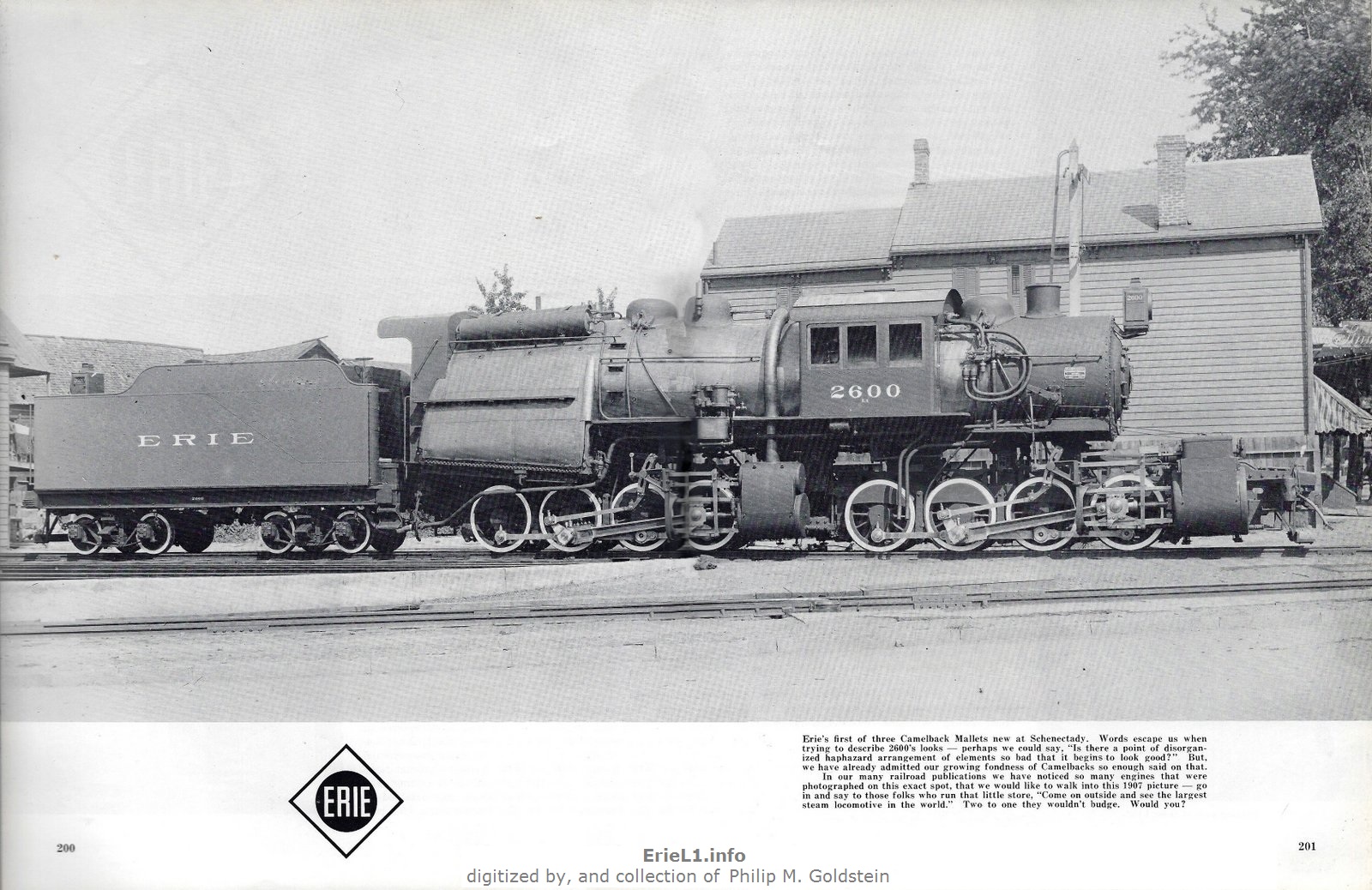

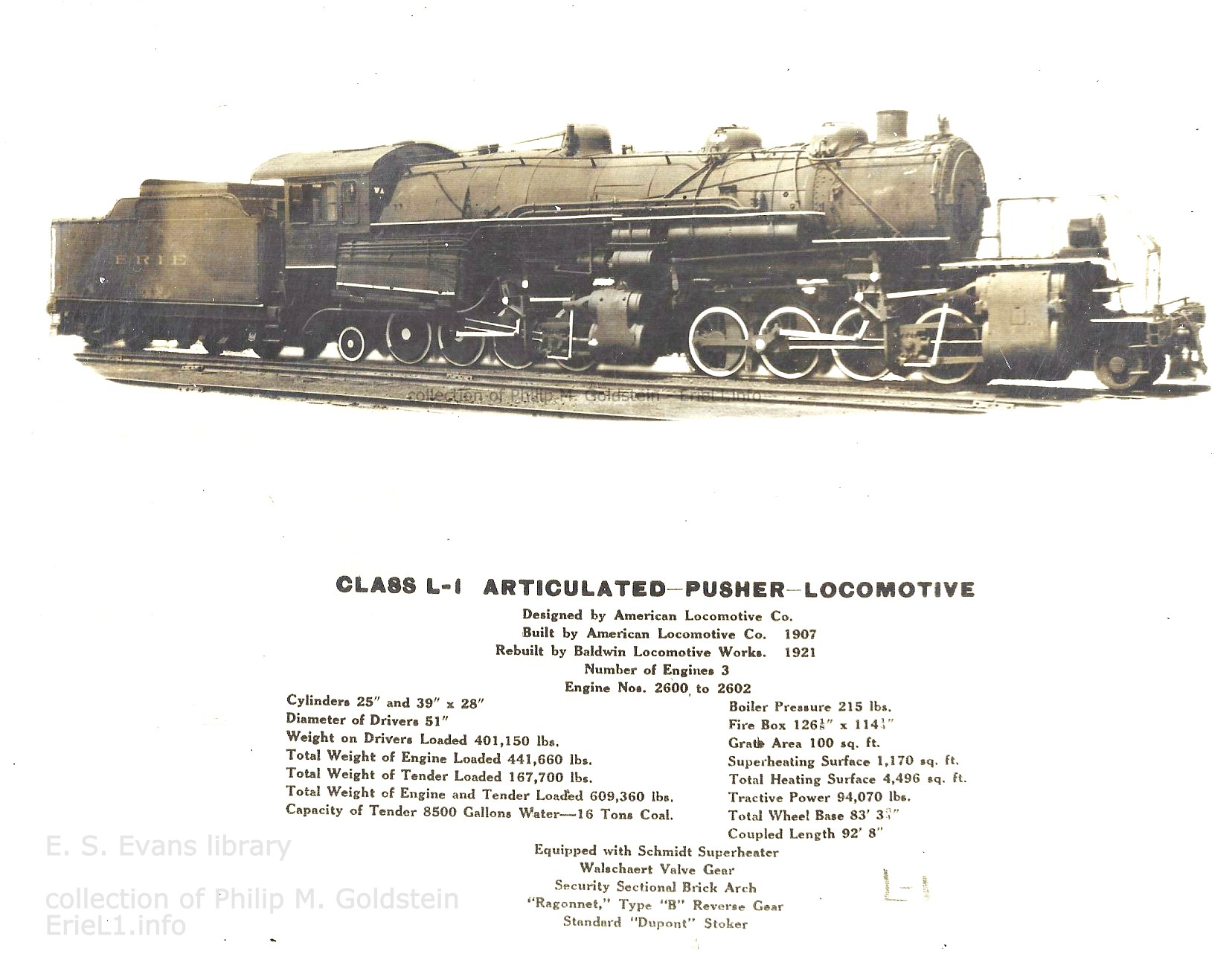

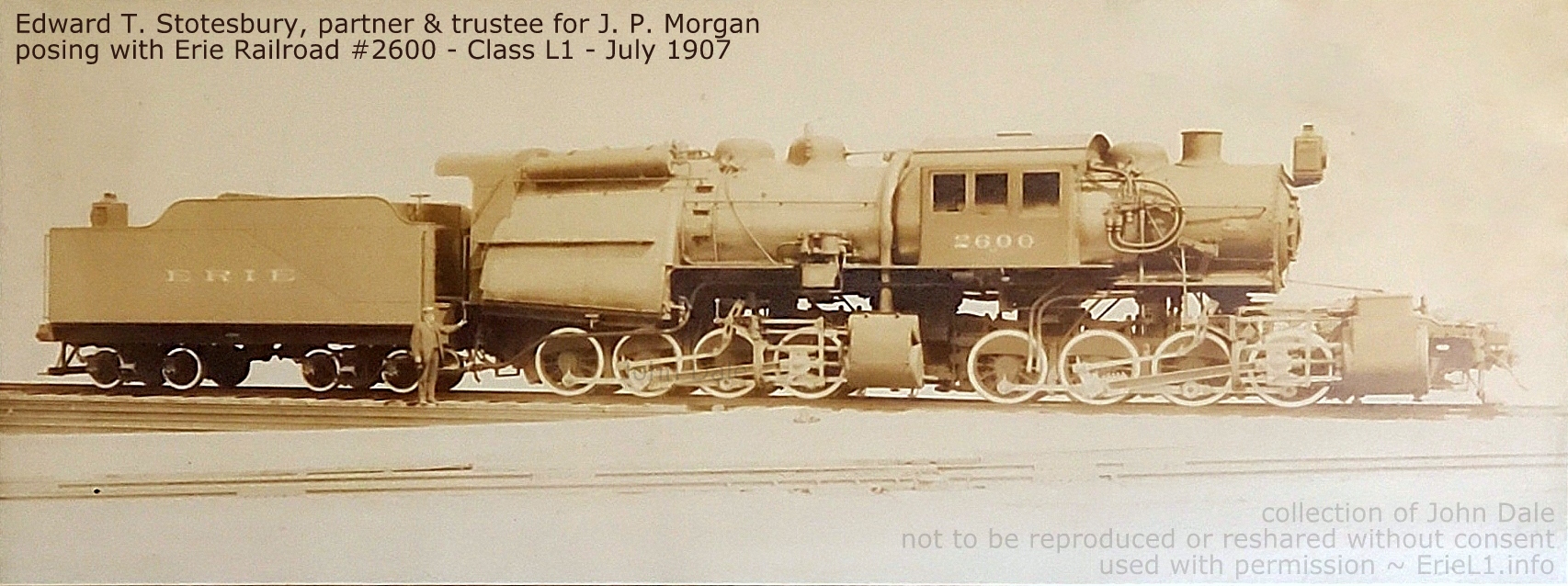

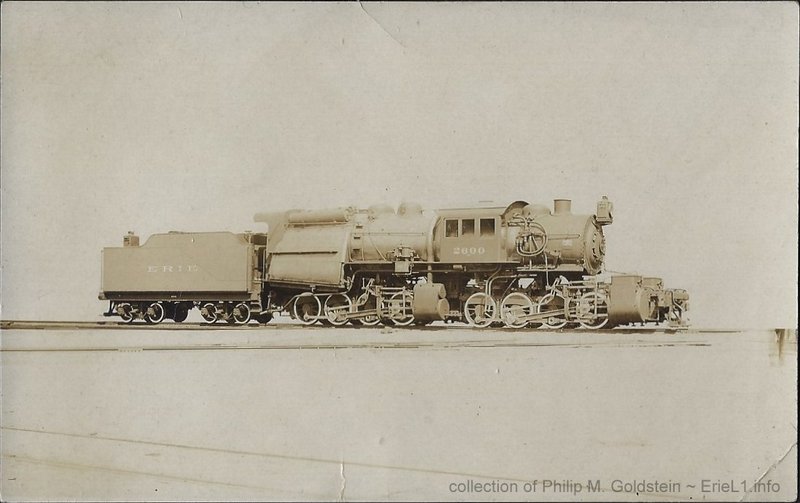

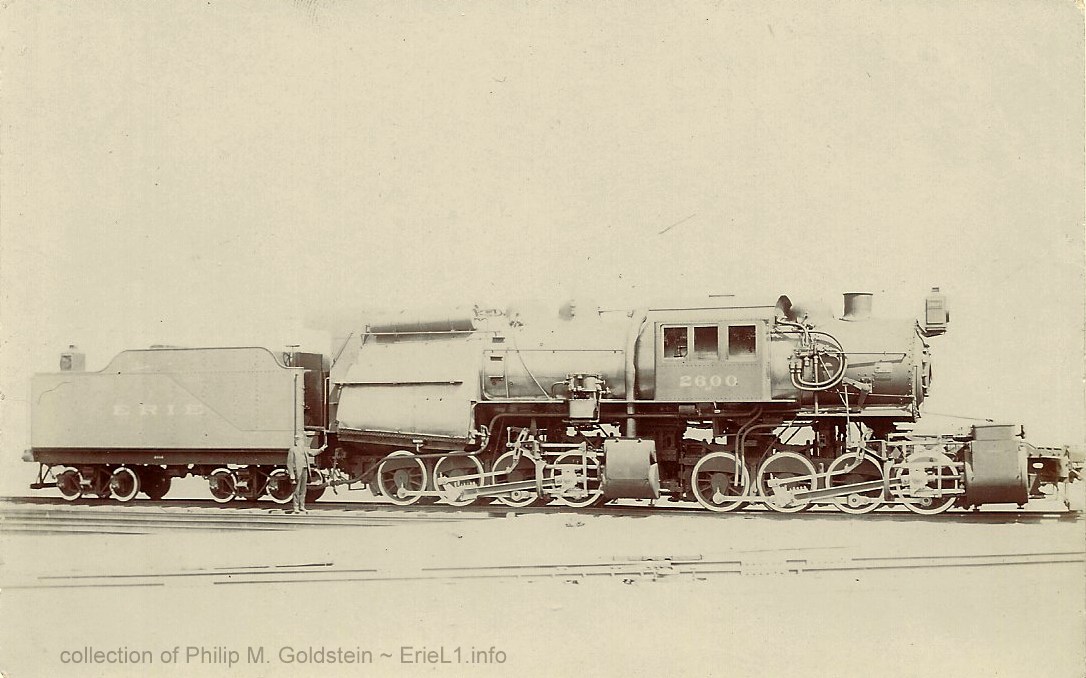

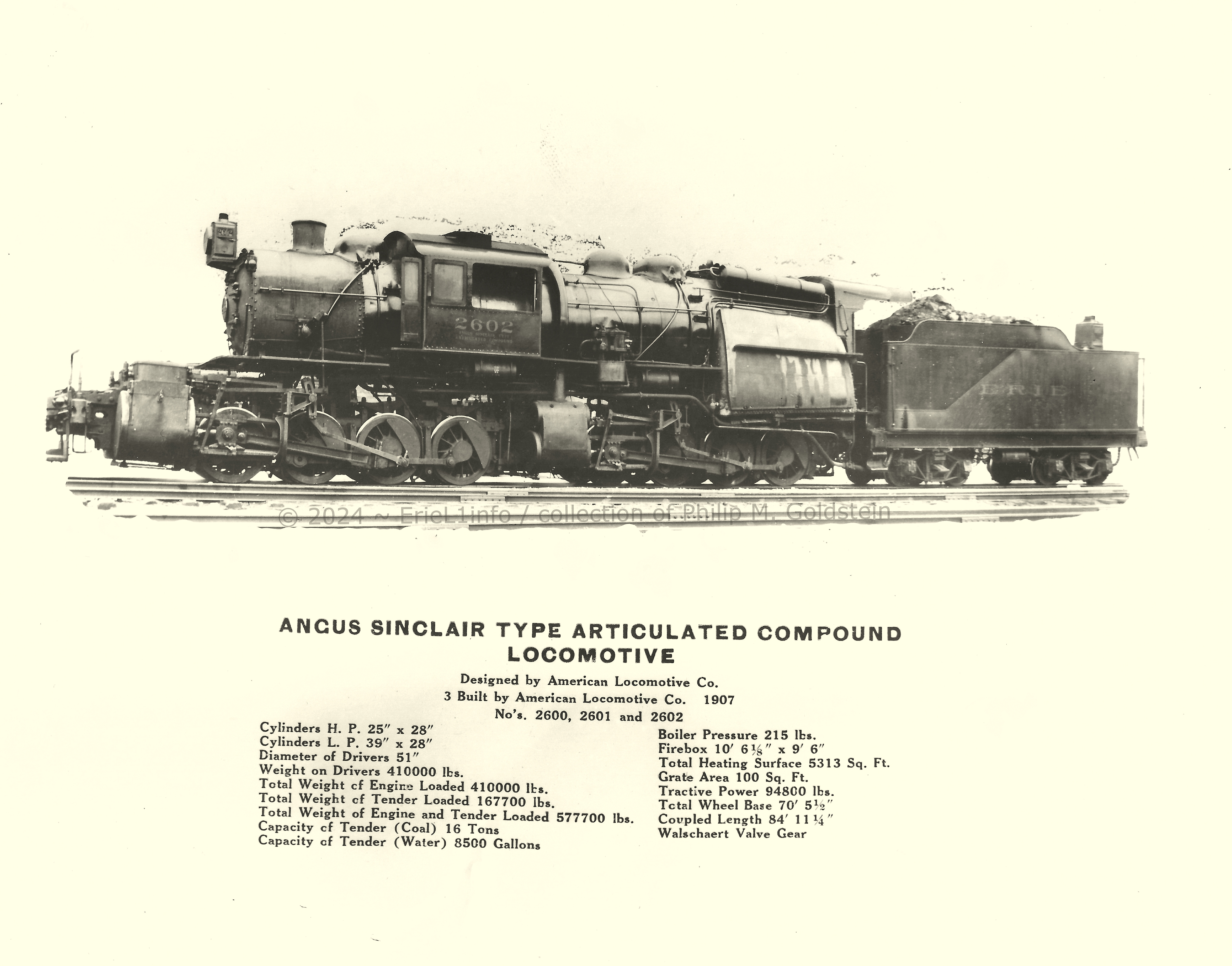

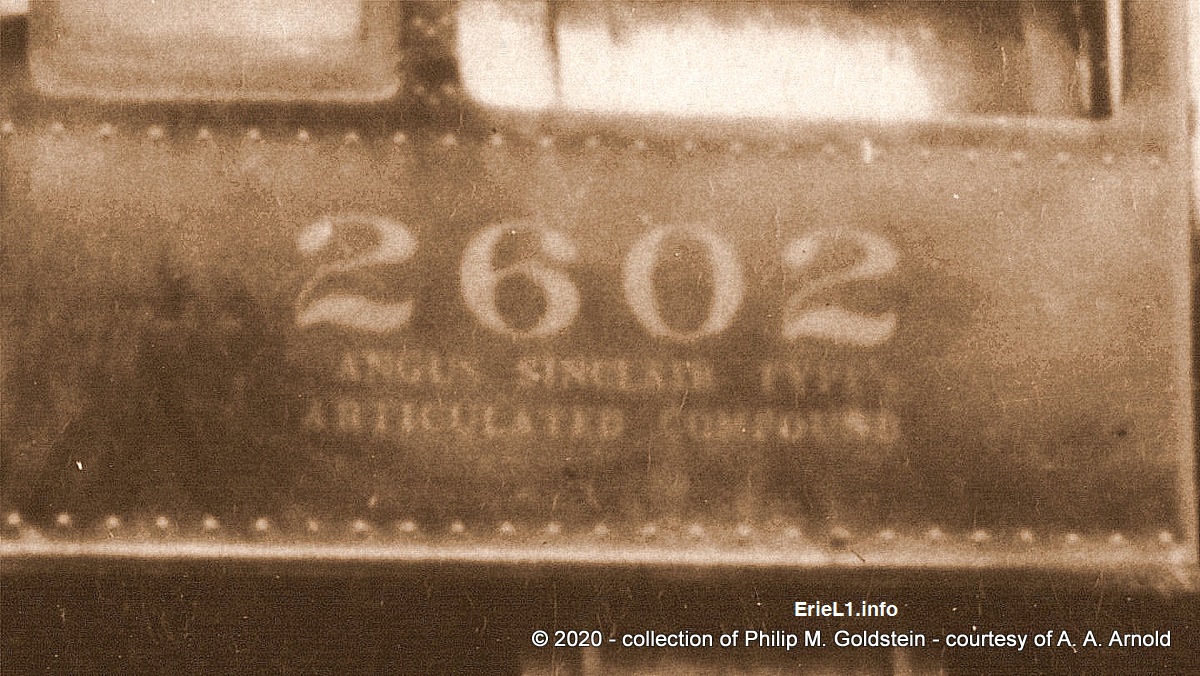

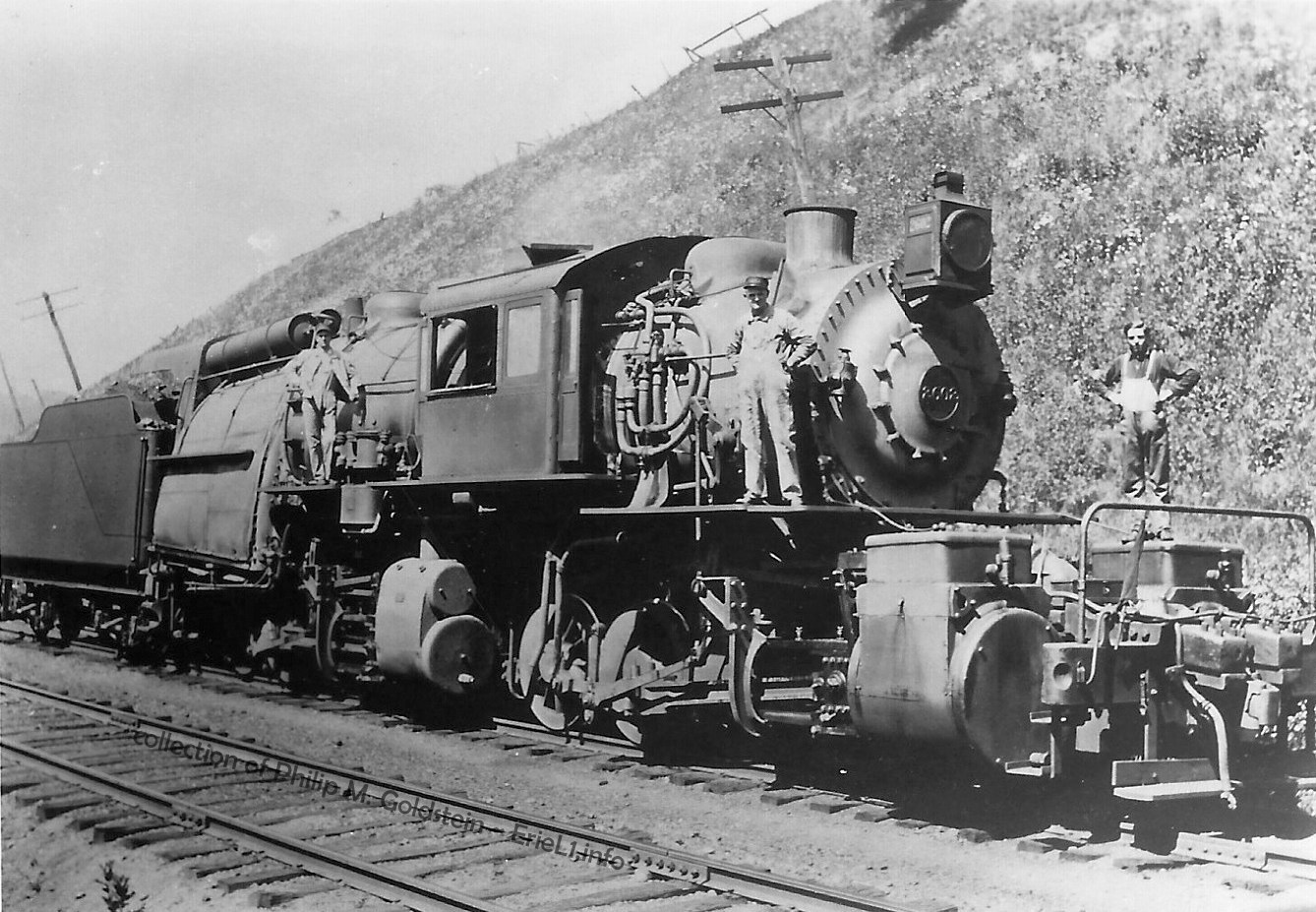

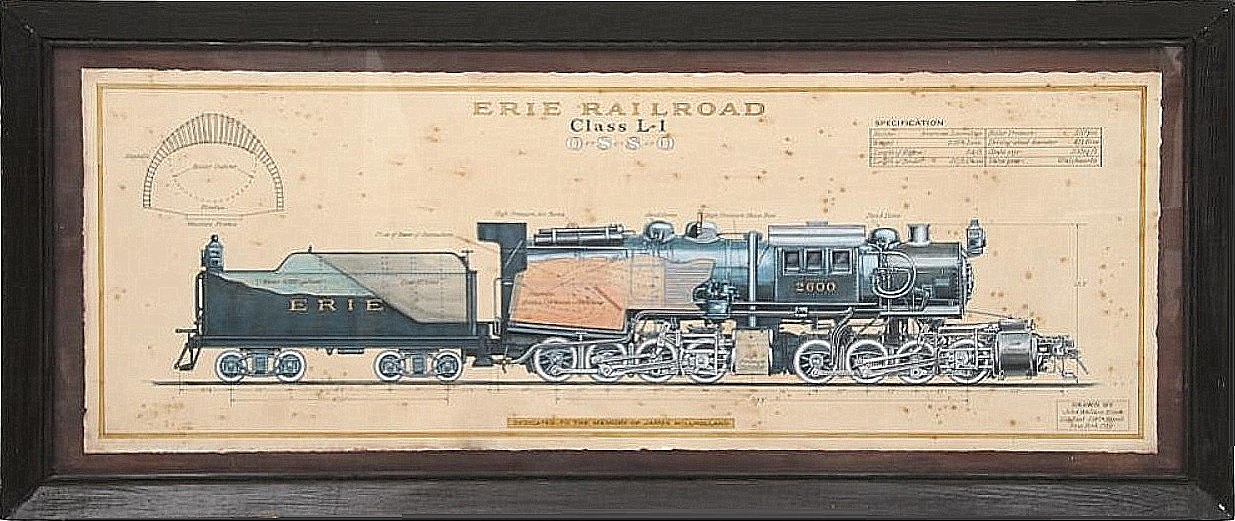

Erie Railroad

- L1 Class #2600

"Angus type" also known as the "Mellin Compound Mallet"

AMERICAN LOCOMOTIVE WORKS

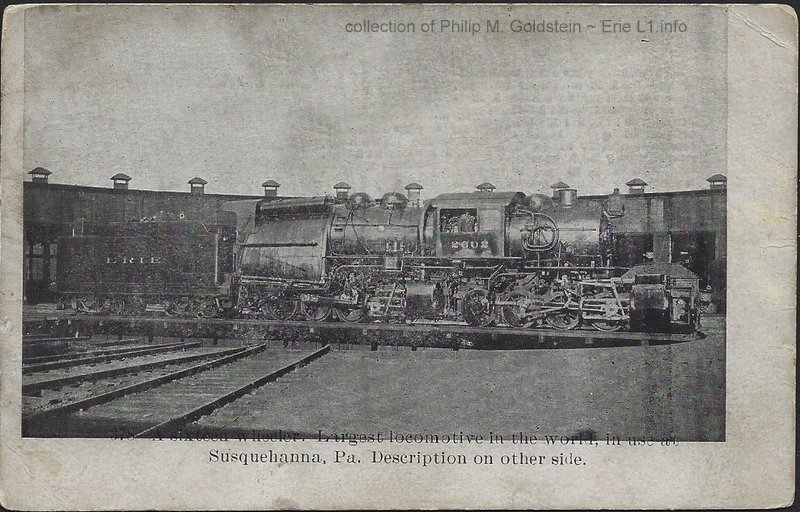

BUILDERS PHOTO - 1907

.

.

.

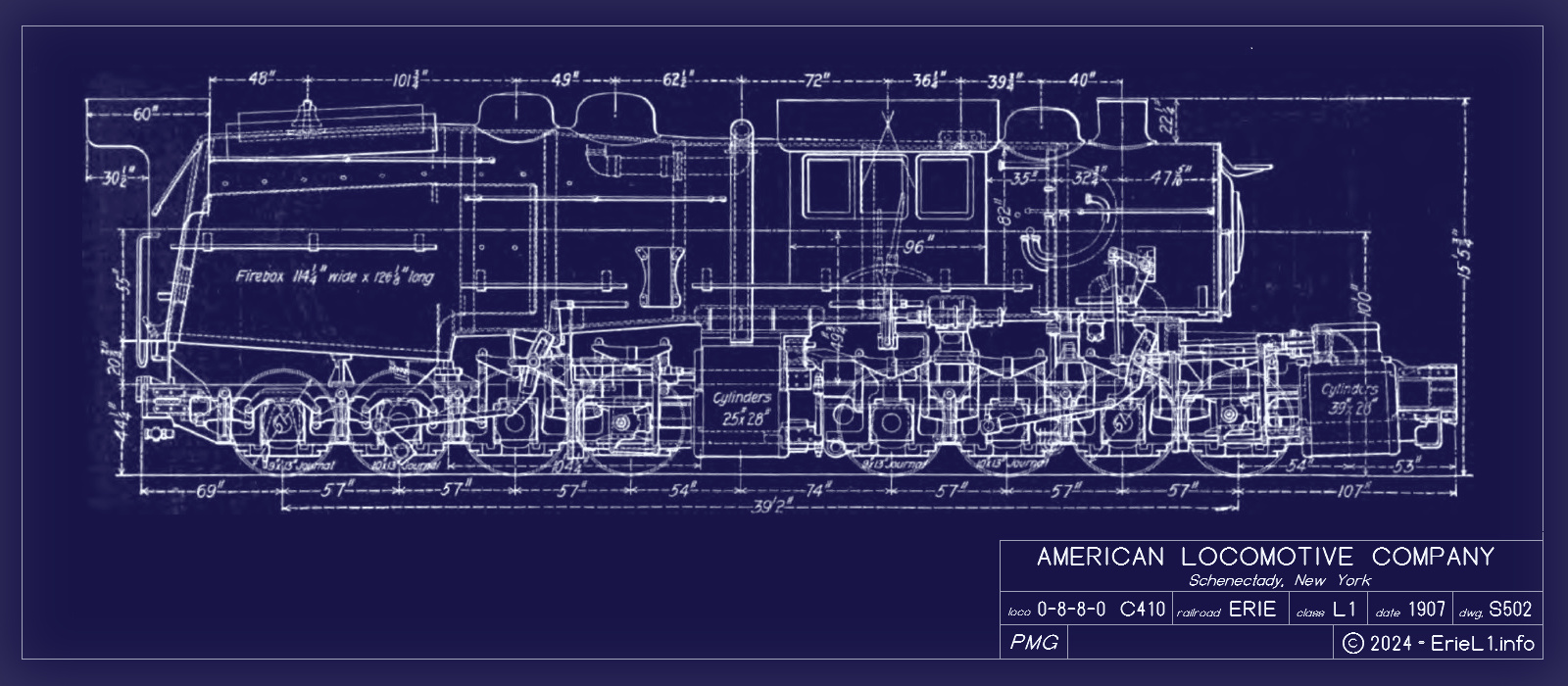

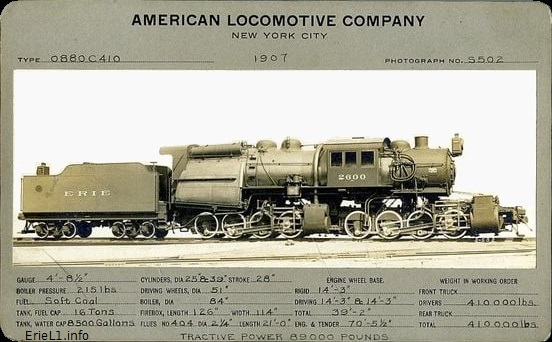

| road: | Erie | cylinders, low pressure (front): | 39" bore x 28" stroke (simple) | |

| Erie locomotive class: | L1 | cylinders, high pressure (rear): | 25" bore x 28" stroke (Mellin compound) | |

| builder: | American Locomotive Co (Schenectady, NY) | valve type, high pressure: | piston |

|

| builder class: | 0880 C410 | valve type, low pressure: | Richardson balanced slide | |

| date built: | July 1907 | valve gear: | Walschaerts | |

| number in class: | three | boiler diameter : | 84" | |

| Erie road numbers: | 2600, 2601, 2602 | number of tubes: | 404 | |

| construction numbers: | 42269, 42270, 42271 | tube diameter: | 2.25" | |

| wheel arrangement: | 0-8-8-0 (articulated) | tube length: | 21' | |

| driver diameter: | 51" | steam pressure: | 215 p.s.i. | |

| total locomotive wheelbase: | 39' 2" | grate area: | 100 sq. ft. | |

| engine wheelbase (individual): | 14' 3" | firebox area: | 343.2 sq ft | |

| total wheelbase locomotive & tender: | 70' 5" | evaporative heating surface (total): | 5313.7 sq. ft. (5666 sq. ft. after rebuilding) | |

| total length, locomotive & tender: | 84' 9¾" (coupler face to face) | superheating surface: | (1170 sq. ft after rebuilding) | |

| minimum curve radius: | 16 degrees | total heating surface: | 6,108 sq. ft | |

| locomotive weight (on drivers): | 410,000 lbs. | tractive force: | 94,070 lbs. @ 90% cutoff; 89,000lbs. @ 85% cutoff | |

| locomotive weight (total): | 410,000 lbs. (441,660 lbs. after rebuilding) | axle loading: | 54,100 lbs. | |

| tender weight (loaded): | 167,700 lbs. | factor of adhesion: | 4.32 | |

| total weight locomotive & tender: | 577,700 lbs. (609,360 lbs. after rebuilding) | indicated horsepower @ 5.0-6.5 mph: | 800 - 1141 | |

| tender capacity (water): | 8,500 gallons | delivered horsepower @ 5.0-6.5 mph: | 584 - 999 | |

| tender capacity (coal): | 16 tons | date rebuilt: | 1921 | |

| fuel: | soft (bituminous) or hard coal (culm anthracite) | rebuilder: | Baldwin Locomotive Works (Eddystone, PA) | |

| to 2-8-8-2, cab moved

to rear, installation

of: Elasco feedwater heaters, Schmidt superheater Ragonnet Type B Power Reverse Gear Standard "Dupont" automatic stokers Security Sectional Brick Arch |

||||

| all scrapped: December 1930 | ||||

.

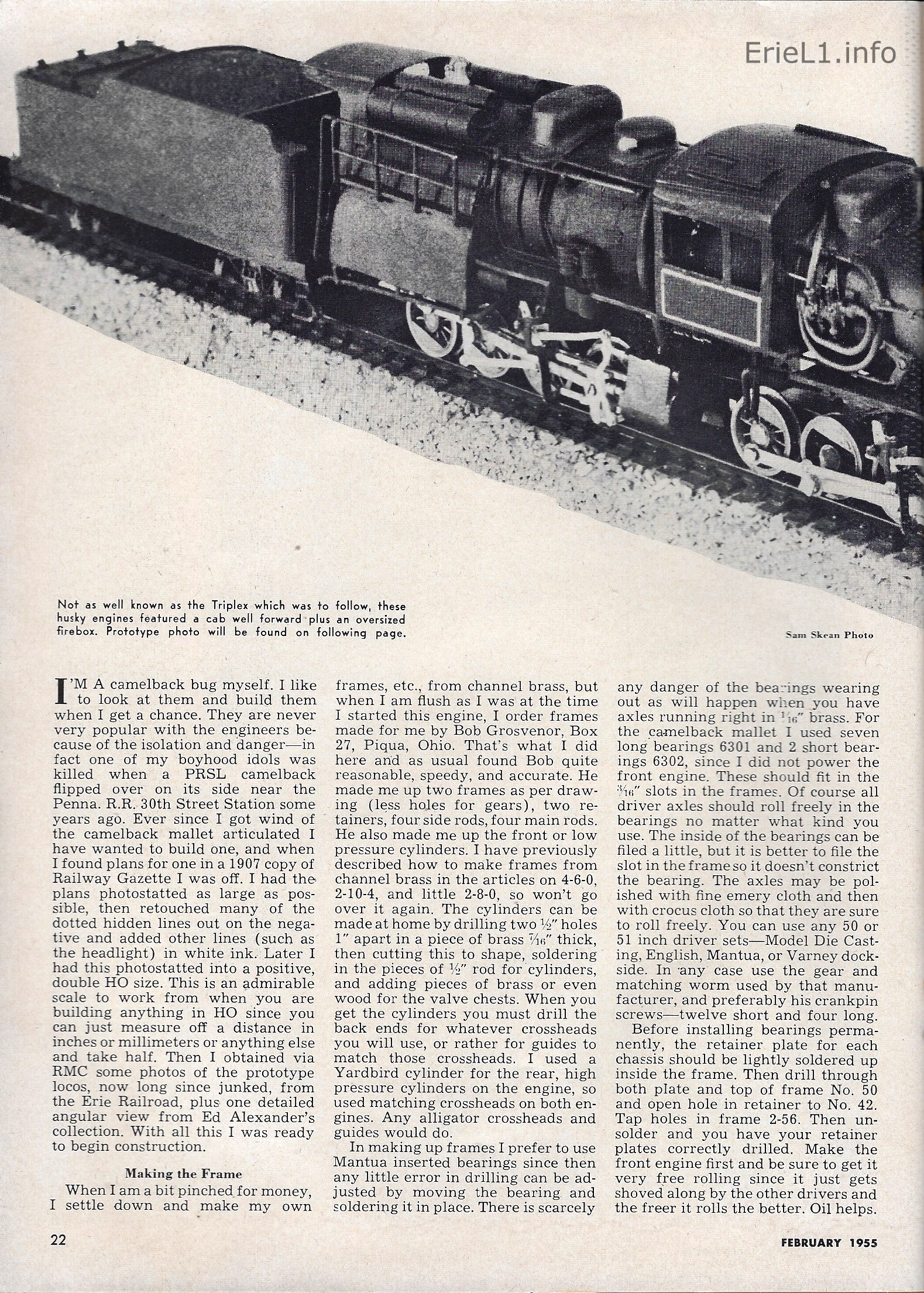

My Interest In Camelback Locomotives:

.

Simply put: this website is dedicated to the existence of three very unique locomotives - the Erie L1 Class 0-8-8-0 Articulated Compound Mallets.

I have always had a particular fondness for camelback type locomotives; and of all the wheel arrangements and configurations built, these three articulated mallet types constructed by American Locomotive Works (Schenectady, NY) for the Erie Railroad are at the top of the list. A close second being the St. Clair Tunnel 0-10-0 side tank Camelbacks.

To say that either of these locomotives were unusual, is an understatement.

The Erie L1's were the seventh, eighth and ninth Compound Mallet articulated locomotives constructed in the United States, following the order to American Locomotive company for a single 0-6-6-0 for the Baltimore & Ohio (#2400 "Old Maud") built in May 1904 (ALCo c/n 27478); and an order to Baldwin Locomotive Works for five 2-6-6-2 for the Great Northern. The Mallet concept, as well as articulation; was rather new to the United States, and still in the process of proving its worth.

But the Erie L1's were first and only camelback articulated Mallet locomotives to be constructed in the United States - and for that matter, the world.

The Erie L1's were further noted as "Mellin compound Mallets", after Carl J. Mellin who patented the improved method of compounding the steam cylinders.

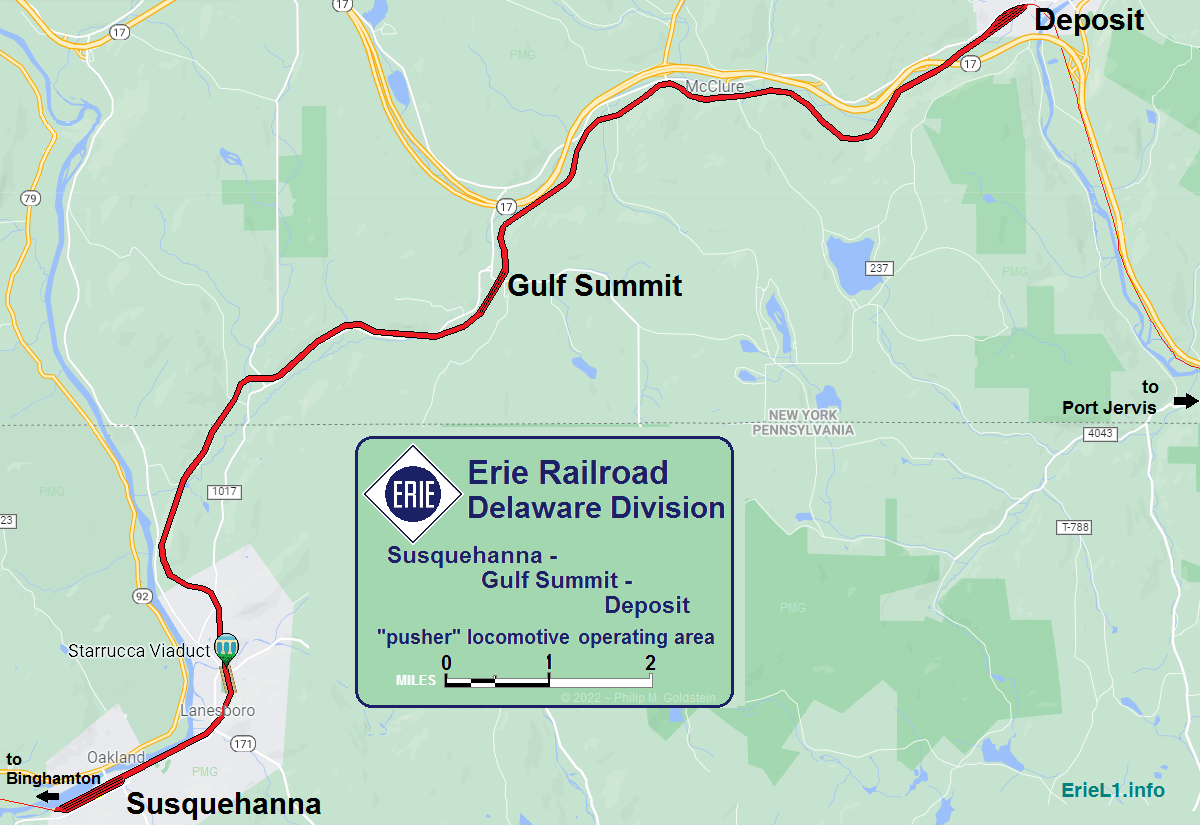

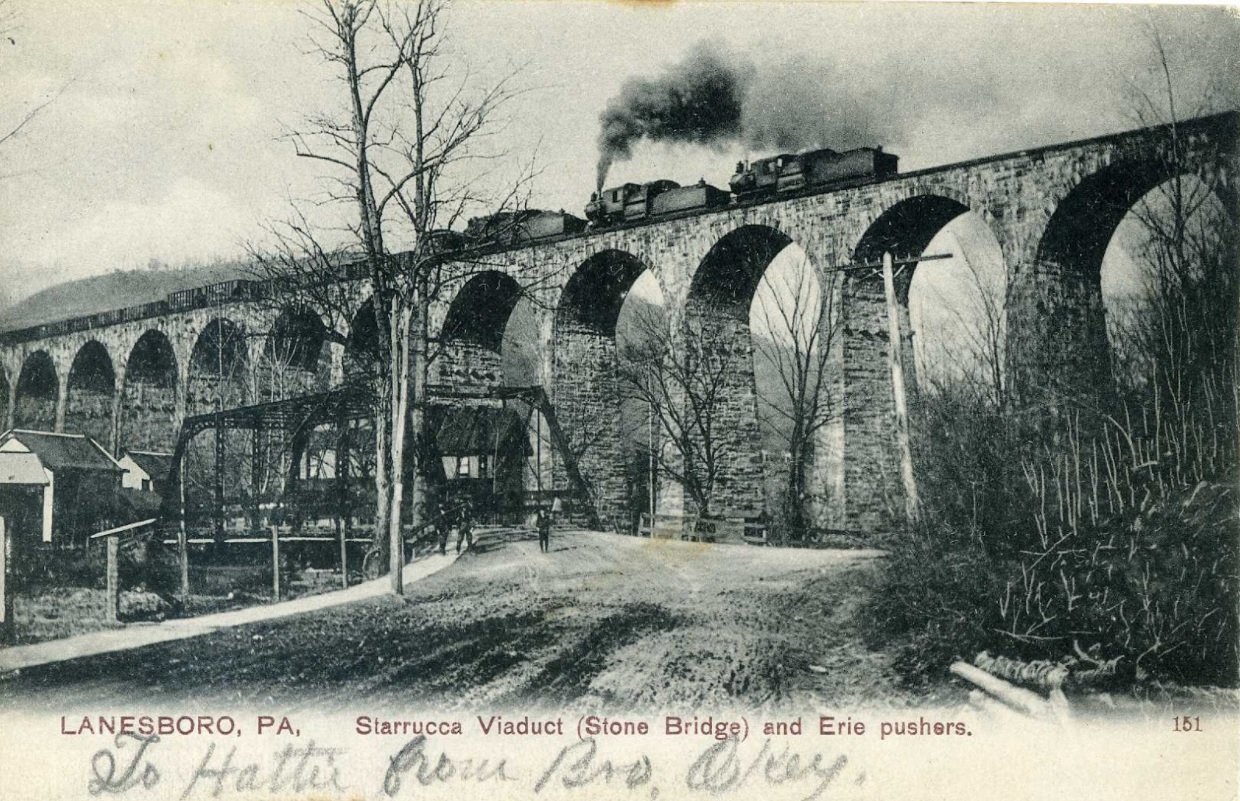

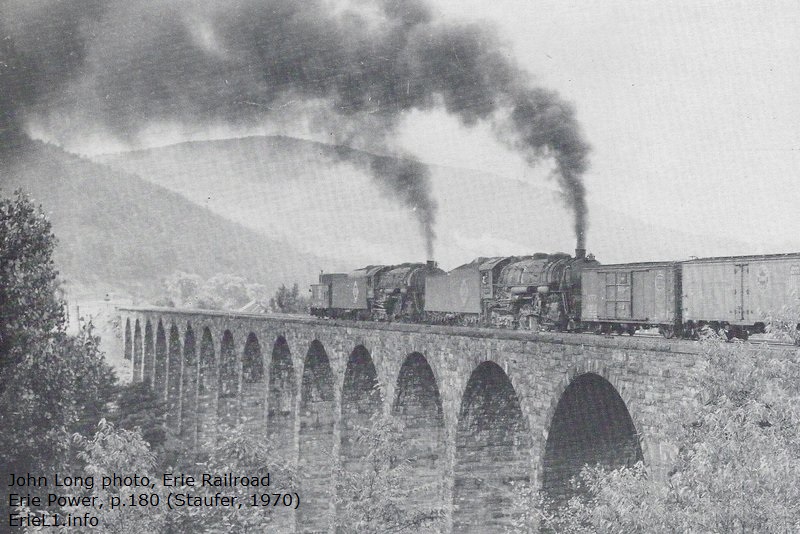

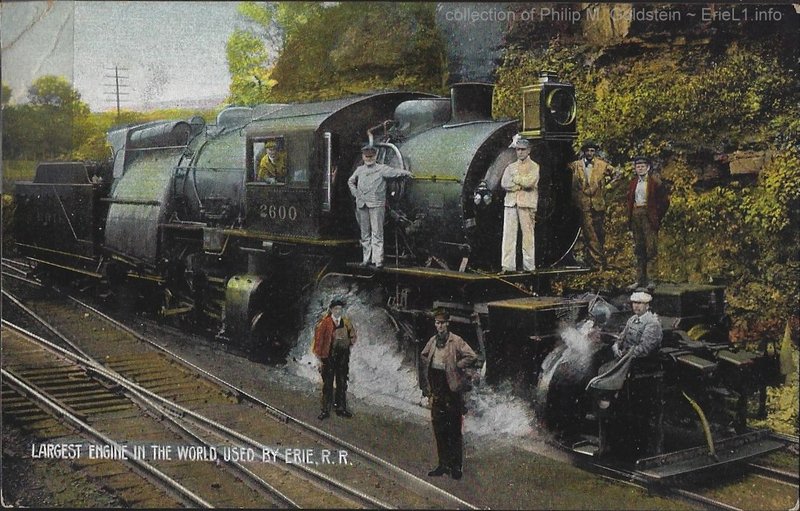

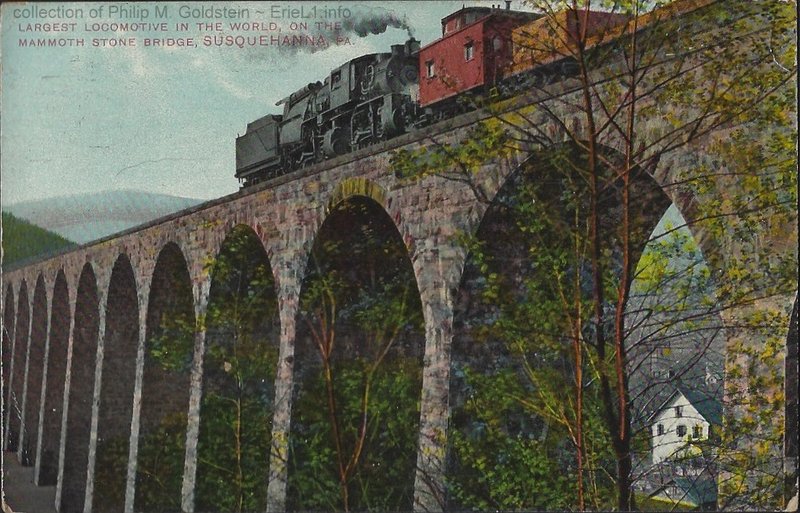

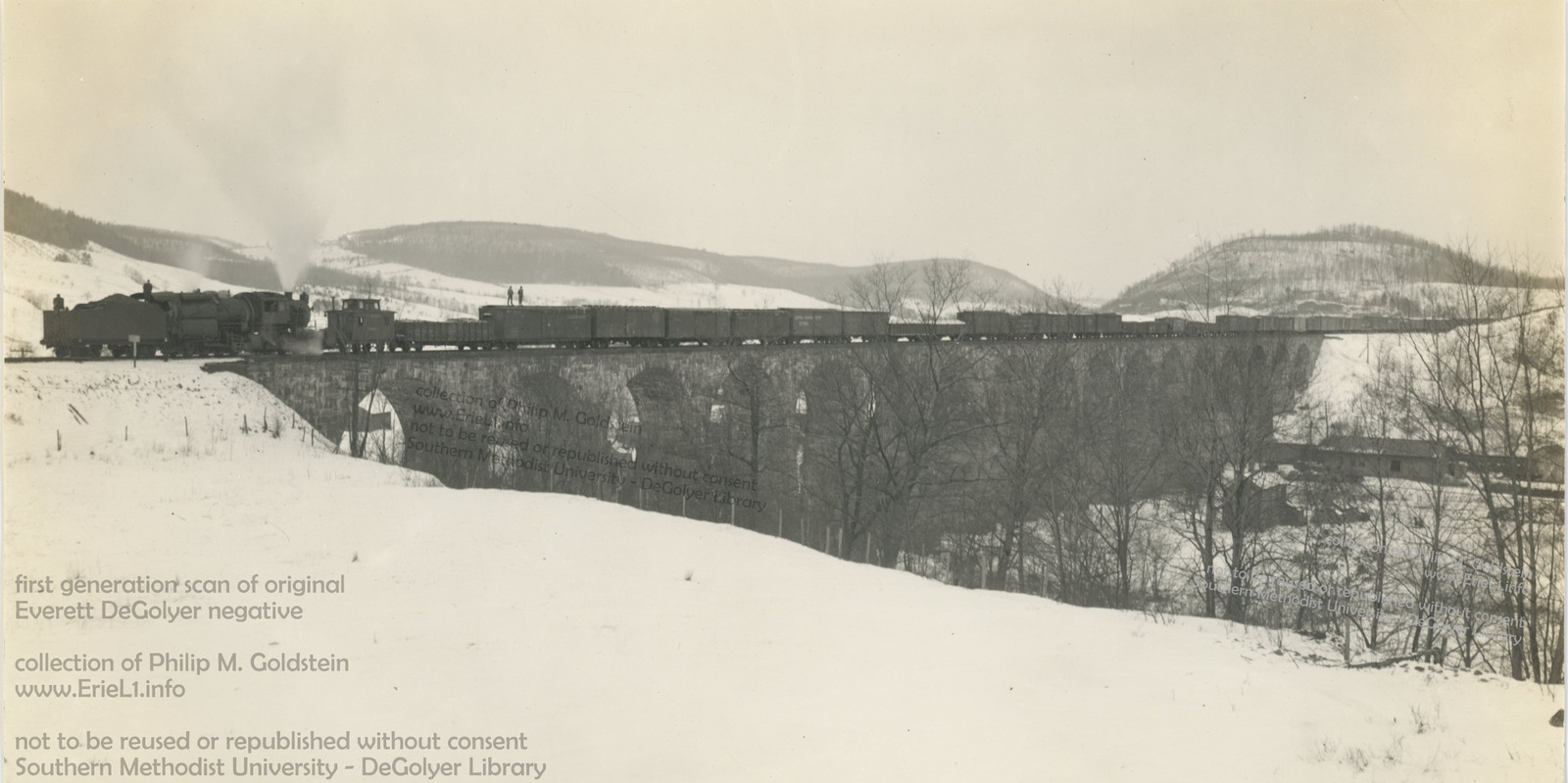

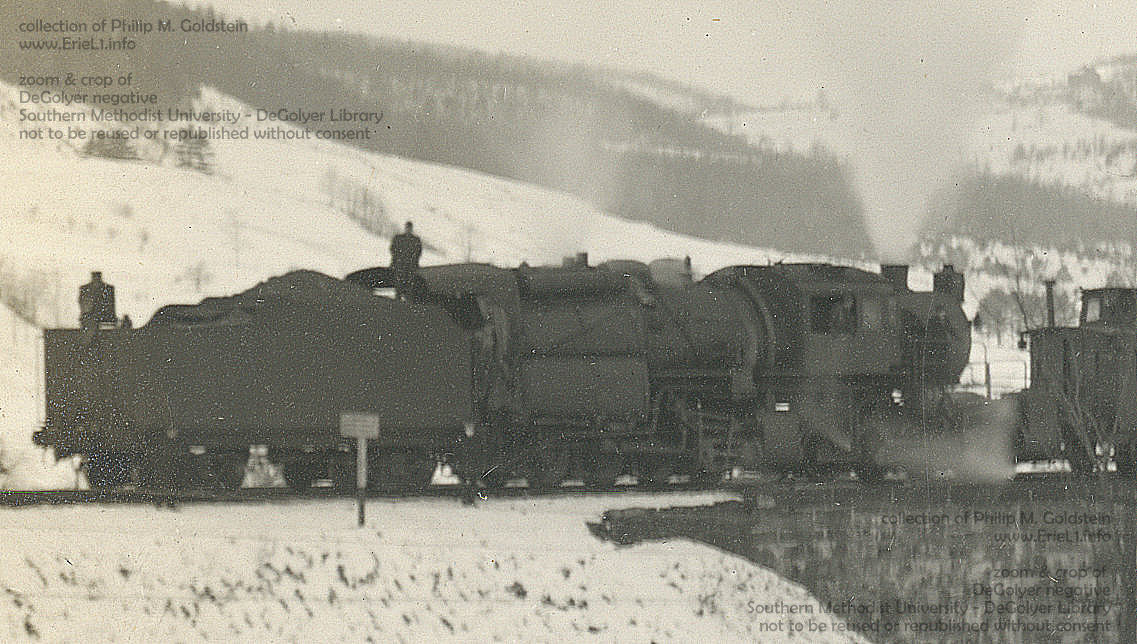

The L1's were designed for and assigned to pusher service over the Gulf Summit grade and Susquehanna Hill, which includes the famed Starrucca Viaduct on the New York - Pennsylvania border, and the line was part of the Erie's Delaware Division.

The L1's pretty much never ventured west of Susquehanna, Pennsylvania; or east of Deposit, New York. However, a publicity image by Erie Railroad shows one of the locomotives in Port Jervis, NY in 1911.

But despite this local limited use, they obviously left their mark on the collective history of railroading as many items were produced to publicize their construction and service; postcards, paintings, and advertising scale models.

These locomotives remain the topic of many discussions today, but unfortunately some of those discussions and comments are rooted myths, misconceptions and misinformation.

So, a great deal of this website is spent in dispelling and proving those myths wrong. That is the premise behind the Real Facts - not Railfan Fiction portion of this website.

As a historian, I am pro-fact and pro-accuracy, and I am as thorough as I can possibly be. I don't merely repeat what I read, I go through the effort of verifying what I read.

"Trust, but verify." Russian proverb

As I gain access to established authoritative

resources, I expand my base of knowledge. I even go out of my way to

collect older technical publications from the 1800's and early 1900's

regarding the subjects I research.

So, a great

deal of the erroneous information that circulates on the internet (and some books) have been proven incorrect on this

website with good old fashioned research,

and posting the

documentation to prove otherwise, hence the Real

Facts - not Railfan Fiction chapters and the 1907 Test and 1908

Thesis chapters showing the

unedited locomotive test results.

Furthermore, it is important to mention that a great deal of the statistics I have stated do not come from crowd-sourced and easily editable Wikipedia; but from established, reputable and authoritative references and sources such as steamlocomotive.com, actual locomotives builders information, as well as industry and technical journals and compendiums from the era the locomotive actually operated.

Since all of the men that actually operated or worked on the Erie L1 are long since gone; some operational information and techniques comes from (and has been corrected) by both active and retired railroaders, especially those with experience in steam locomotive operation.

But unfortunately, due sometimes in part to novice railfans not understanding the technology that existed at that time when compared to todays standards; and sometimes in part to biased opinion; there is an inordinate amount of misunderstanding (or just plain bad assumption) on their parts regarding these Erie locomotives (and to be frank, other topics as well.)

Regrettably, this

erroneous info makes its way onto the web and before you

know it its being parroted in modeling forums, Facebook groups and

railfan

threads.

- "A lie gets half way around the world before the truth has a chance to put its pants on." Winston Churchill

- “The irony of the Information Age is that it has given new respectability to uninformed opinion.” John Lawton

or if you prefer:

.- Damnant quod non intellegunt.

Translation: They condemn what they do not understand.

I have been told I can be long winded, and it's been said I take the long way to get where I'm going, especially when disproving a fallacy.

But it is no longer enough to simply inform someone their information is incorrect, especially so in Facebook Groups, Reddit and internet forums. People now become defensive, obstinate, argumentative, and indignant. Even when I have been polite.

Now, it seems it has become necessary to put all the data in black and white, and literally hammer this time and time again in front of the misinformed, to get them to realize the error of their ways. And sometimes that isn't even enough. As I grow older, I am sorry to say I have lost a lot of patience and diplomacy in dealing with these types. You may be better acquainted with them as the:

.

This is why you will find extensive history and information pertaining to anthracite burning locomotives, what the difference between anthracite and anthracite culm is and so forth.

Because just another "fan page" on a locomotive design and bare basics information might not educate those types.

I know some of you will appreciate the effort.

Naturally, if I am in error; please feel free to contact me and I will make a good faith effort to review the facts you provide.

Regards, and enjoy the website!

Philip M. Goldstein

bedt14@aol.com

|

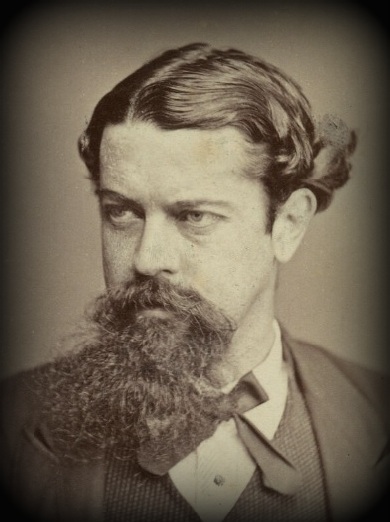

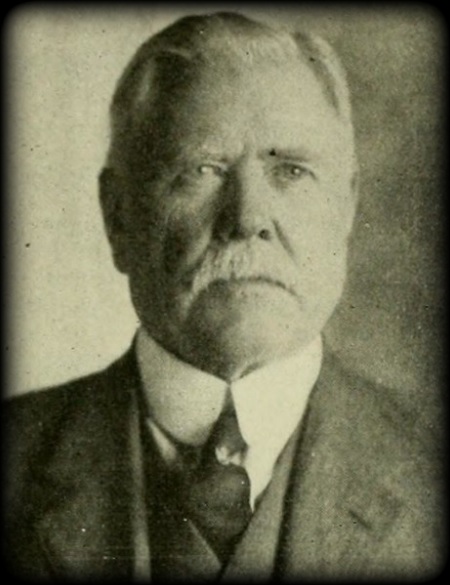

Ross Winans |

| October

17, 1796 - April

11, 1877 Vernon Township, New Jersey, USA |

|

In 1828, he developed a friction wheel with outside bearings that established a pattern for future railroad wheels. In the late 1820s, he became associated with the Baltimore & Ohio RR, entering their service as an engineer (designing). His first task was to help Peter Cooper build the revolutionary "Tom Thumb" steam locomotive. In 1831, he would be appointed assistant engineer of machinery on the B&O.In 1835, he went into partnership with G. Gillingham and in 1836, they took over the 1834 lease of the B&O Company's shops at Mount Clare and continued the manufacturing of locomotives and railroad machinery. In 1841 however, he opened his own shop adjacent to the Mt. Clare Shops. Winans was a pioneer in the development of coal-burning steam locomotives, including the use of anthracite coal; and substituting it for the less efficient wood-burners of the era. Winans set trends in locomotive and car design rather than followed them. His steam locomotives, popularly known as "Crabs," "Muddiggers," and "Camels"; were used all over the expanding Northeast U.S. rail network. From 1843 to 1863; Winans delivered approximately three hundred locomotives to twenty-six different American railroads. He is also credited with being the first US locomotive manufacturer to export a locomotive to Europe. The B&O was Winans' largest locomotive customer, with 140 locomotive deliveries going to that railroad alone. Winans' second best customer was the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad. These two customers represented 70 percent of Winans' total sales. James Millholland, master mechanic of the Cumberland & Pennsylvania RR (and then Philadelphia & Reading), worked with Winans on Cooper's "Tom Thumb", and was quite familiar with keeping these "Camel" engines running, and making improvements to them. Winans' customer relations were simple—he built engines his way, and you bought them. While he was eccentric, his locomotive business made him independently wealthy. Bored with the business, and having a design disagreement with the B. & O., he closed his shops and pursued other endeavors. |

|

|

|

|

|

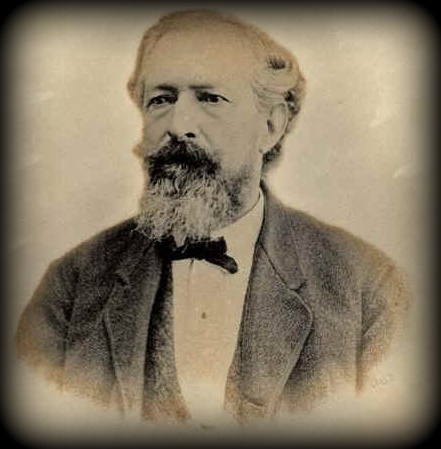

Zerah Colburn |

| January

13, 1832 - April 26, 1875 Saratoga, New York, USA |

|

Colburn was the nephew of his namesake, Zerah Colburn, a noted prodigy in advanced arithmetic. With no formal schooling, Colburn was a teenage prodigy in engineering. Barely in his teens at the start of the railroad boom, he found work in Lowell, Massachusetts as an apprentice in the "drafting room" of the Lowell Machine Shops. Colburn had a career of breakneck speed. He was a restless man, quick of brain and also quick of temper. He would fall into jobs and fell in with people; but repeatedly fell out with them too; but as he moved about the various locomotive works of New England, he gained experience as well as an eye for engineering detail. He also produced his first book, "The Throttle Lever". Designed as an introduction to the steam locomotive, this became the standard U.S. textbook on building locomotives. The book took Colburn, then not even 20 years old, deeper into the world of publishing, but it also earned him the wider respect of railroad men across America – both locomotive builders and train operators. Colburn worked or was associated with a number of locomotive works between 1854 and 1858, including: Baldwin Locomotive Works; Tredegar Locomotive Works at Richmond, Virginia; Rogers Locomotive Works; and the New Jersey Locomotive and Machine Company. While at NJL&M, Colburn began construction of the "Lehigh" for the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western RR in February 1855. It was of the 0‑6‑0 type, with an overhanging firebox of 7' 6" in width. The first such use of the wide firebox for anthracite. Colburn's intention was to use a firebox six feet long, but he left the New Jersey Locomotive Works in a disagreement and before the "Lehigh" was completed, and the builders reduced the length to 4' 6. The locomotive proved a poor steamer, and the firebox was subsequently lengthened to six feet, as proposed by Colburn. Ultimately; overwork, an addiction to laudanum, alcohol and poor financial management took their toll on his mental health. In trying to ease his mind; he became increasingly delighted by London prostitutes whose pleasures he much enjoyed, but where he contracted syphilis. Colburn, sensing the impending shame offered by Fleet Street journalists and their diligence to seek out and publish the "truth", he became depressed and reckless, leading to his return to the U.S. – where he found himself disowned by his wife and daughter, of which led to his eventual suicide at the mere age of 38. |

|

|

|

|

|

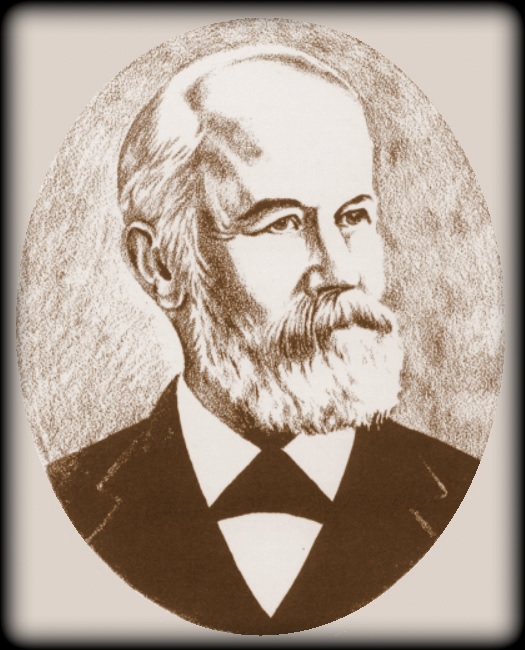

James Millholland |

| October

6, 1812 - August 1875 Baltimore, Maryland, USA |

|

Millholland had the honor of working on Peter Cooper's "Tom Thumb" locomotive (along with Ross Winans), and found so much pleasure in working with it, he dedicated his profession to railroad locomotives. Railway master mechanic for the Philadelphia & Reading; and designer of the anthracite firebox for that railroad (and in separate but parallel development with Colburn); as well as many other inventions, which became standard on American railroads. Also an early user and advocate of the superheater, the feedwater heater, and the injector. Inventions and contributions include the cast-iron crank axle, wooden spring, plate girder bridge, poppet throttle, initial design of the anthracite firebox, water grate, drop frame, and steel tires. |

|

|

|

|

|

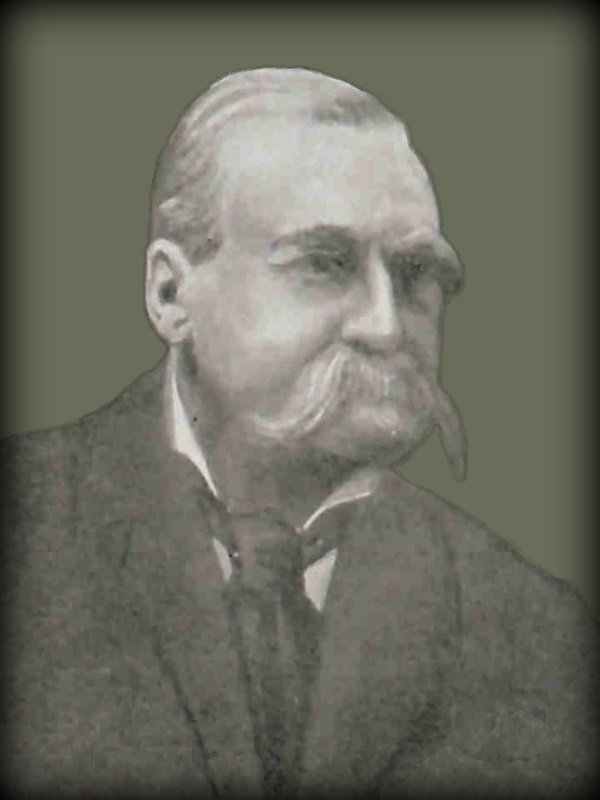

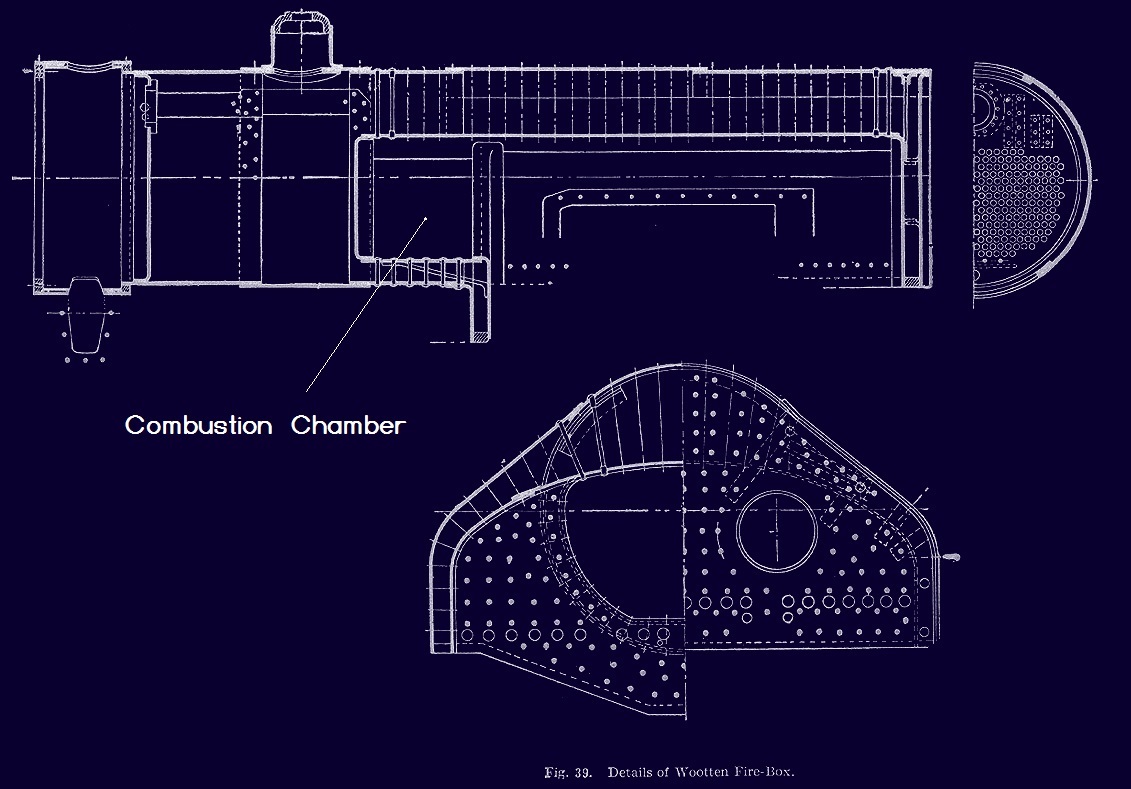

John E. Wootten |

| December 23, 1822 -

December 16, 1898 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA |

|

Wootten would assume Millholland's position of master mechanic; when the latter resigned from the P & R. While James Millholland first designed a firebox for burning anthracite; it would be Wootten that would go on to perfect the final result for burning anthracite culm, and have his name inextricably associated with the design. Wootten also realized in the mid-1870s, when he held the position of Superintendent of Motive Power (and soon after General Manager) of the Philadelphia & Reading RR; that if a firebox be could be designed to utilize the vast unwanted quantities of anthracite culm (mine / breaker waste) in the Northeast United States; a vast savings in the cost of operation of steam locomotives could be achieved. Due to its width and placement, the design of the Wootten firebox required the repositioning of the engineers cab which resulting in the Camelback locomotive type. This is without a doubt the most significant part of the Erie L1 design, not to mention all those Camelback style locomotives that both preceded and succeeded it. |

|

|

|

|

|

Anatole Mallet (pronounced mal-LAY - rhymes with ballet) |

| 1837 - October 1919 Lancy, Switzerland |

|

Mechanical engineer, inventor of the first successful compound system with articulated railway steam locomotive, patented in 1874. He developed the boiler over articulated frames containing drive wheels and compound cylinder placement (in contrast to the Beyer or Garrett types of articulated locomotives); and of which the Erie L1 fell into this Articulated Mallet design type. This Mallet style of locomotive became popular not only for the heavy freight drag or pusher operations; but for timberland harvesting firms with excessive curvature and steep grades as well. |

|

|

|

|

|

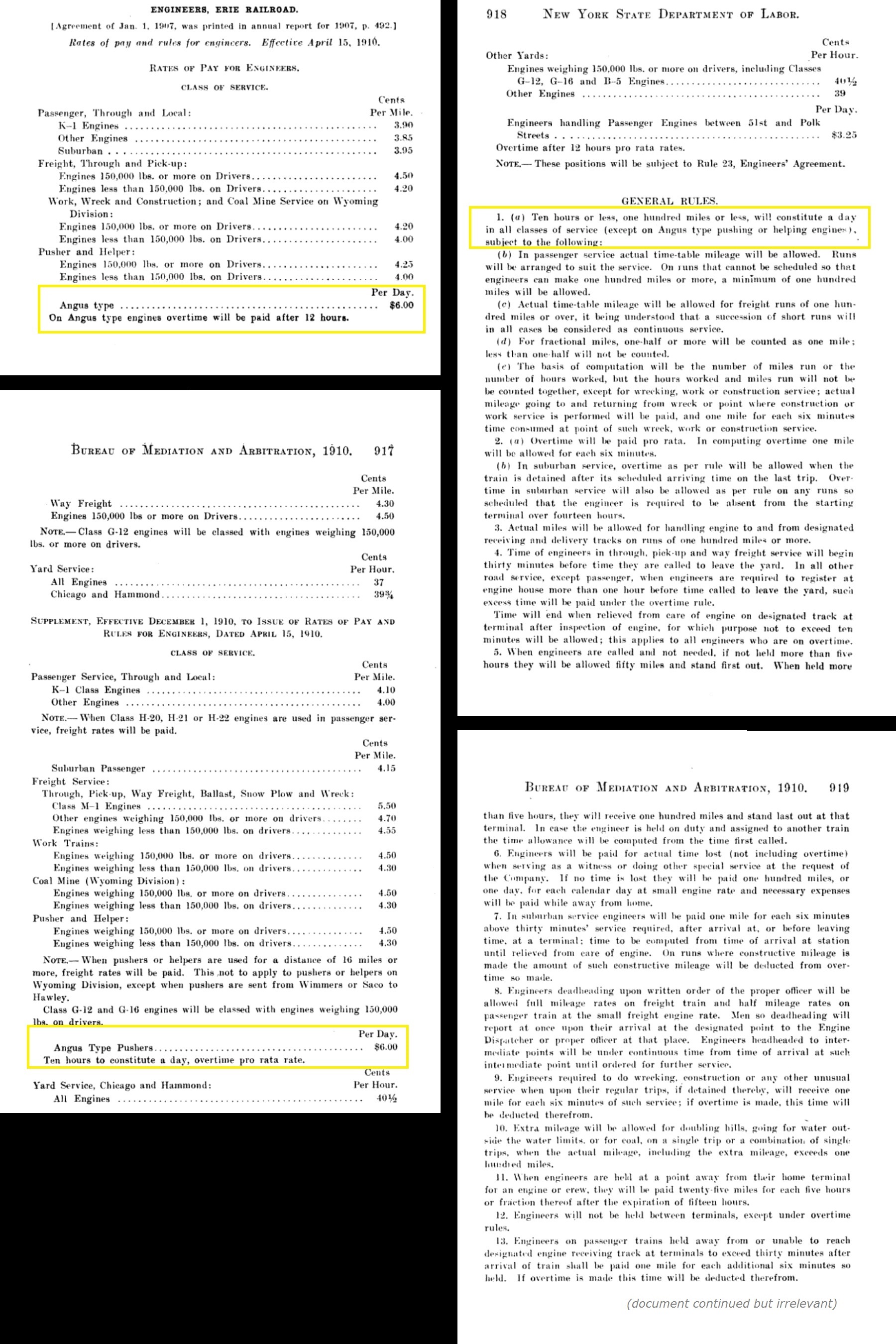

Angus Sinclair |

| 1841- January 1, 1919 Laurence-kirk, Mearns, Forfar, Scotland |

|

Erie Railroad special instructor, locomotive engineering, publisher of "Railway & Locomotive Engineering" technical journal and the "Development of the Locomotive Engine", one of, if not the most comprehensive history on the construction of locomotives. Sinclair was respected by all designers and master mechanics, no matter which railroad they worked for. Sinclair's "contribution" to the Erie L1, was that he is believed to have stated before the L1's were completed, that the L1 would "dry up the country's canals and make water transportation obsolete". While this was clearly hyperbole, it is understood that the Erie RR saw fit to honor this statement by assigning Sinclairs' name to the class of locomotive: "Angus" |

|

|

|

|

|

While all the men mentioned thus far have contributed to the advancement of steam locomotives, or at least certain design philosophies; it is this man that is most directly and specifically involved in the design and construction of the Erie L1 Articulated Compound Locomotives: |

|

|

Carl J. Mellin |

| February

17, 1851 - October 15, 1924 parish of Hagelberg; Skaraborg County; Västergötland region, Sweden |

|

Mechanical engineer and designer of steam locomotive and marine steam propulsion systems. From 1877 to 1887, after completing technical studies, apprenticeships and internships; he was employed by Robert Napier & Son, Glasgow, Scotland; as a designer for maritime propulsion systems, as well as the ships themselves. He then was employed by Atlas (now Atlas Copco) in Stockholm, Sweden. He immigrated to the United States in 1887. In 1894, he obtained the position of chief engineer for the Richmond Locomotive Works, in Virginia; and in 1902 began employment as a consulting engineer for American Locomotive Works of Schenectady, New York. Here, Mellin directed the design office as well as supervised the workshops for the construction of propulsion machinery for US Navy battleships; but his forte was designing locomotives. He is recognized for the designing the "The Spirit of the Twentieth Century", a 4-4-2 "Atlantic" built for the "Big Four" (the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railway) exhibit in the Palace of Transportation at 1904 Worlds Fair / Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri. This exhibit earned him a gold medal. Specific to this website, Mellin was supervising engineer for American Locomotive Company when the Erie L1's were designed and built, and he developed and patented the specific compound cylinder system used on the Erie L1 design. |

|

(No, they weren't the same thing.)

- That's Wootten, with two O's and two T's;

- Camels vs. Camelbacks,

and- Anthracite vs. Anthracite Culm

Some readers may not know the reason for the cab astride the boiler arrangement of Camelback locomotives, so it is here that I will take some time to explain. It is quite lengthy so be forewarned.

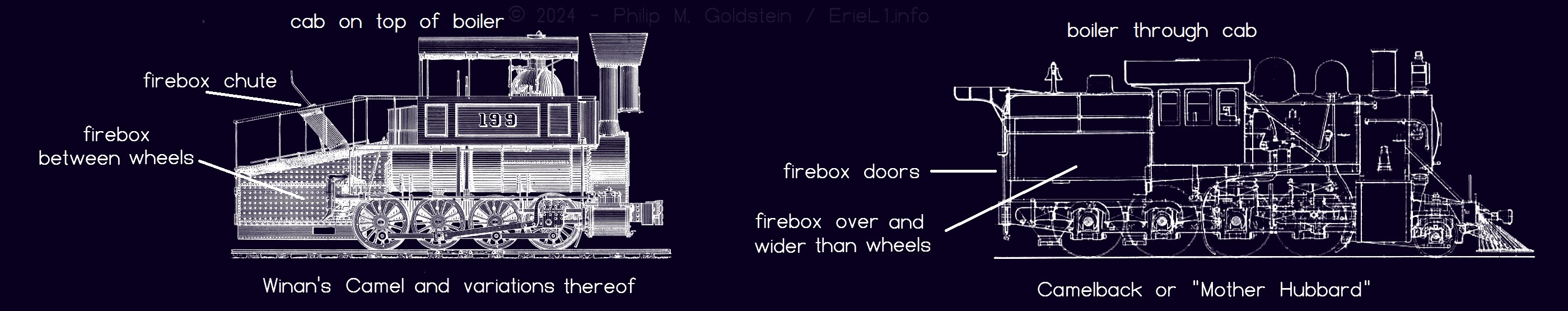

First, it bears mentioning that there were two distinct types of steam locomotives that had center mounted cabs. They are often interchangeably called camels and camelbacks, but this is incorrect; each type were specific to their own design.

The original "Camel" type locomotives were built by Ross Winan, a prolific railroad inventor of the era. First built in 1848; these "Camel" locomotives were designed to burn anthracite coal appropriately sized for locomotive use; not anthracite culm. These locomotives were designed as slow speed, heavy haul freight locomotives and all were originally of the 0-8-0 wheel arrangement. Over 200 were produced.

The outer perimeter of the firebox was contained completely between the wheels and over the axles. They had sloped top fireboxes further defined by a loading chute on top of the firebox in which to feed coal. Originally, coal was fed from a elevated platform on the tender, and not from the tender deck; but this was later modified and the use of fire doors on the rear became standard.

So successful was the locomotive, that the design was copy-catted by several builders as well as subsequently improved upon by Samuel Hayes, Master of Machinery at Mount Clare Shops of B&O RR; and by Matthias Baldwin of Baldwin Locomotive Works, among others. Even the Altoona Shops of the Pennsylvania RR rebuilt at least one Winan's Camel.

As these locomotives were rebuilt, other wheel arrangements (namely 2-6-0 and 4-6-0) were adapted to the Camel design. Nevertheless, it is this design of locomotive and this design only that should be referred to as "Camels", and are seen below left.

Camelback or "Mother Hubbard" locomotives had firebox doors on the rear, a firebox that extended over and wider than the wheels, and the boiler went through the cab, not under it. They were designed to burn anthracite culm.

..

2.2:

Anthracite vs. Anthracite Culm

Before commencing with the next chapter; it is imperative for the reader to understand that at this juncture, firebox development was designed to use screened or sized anthracite; not anthracite culm, which was small, and irregularly sized waste.

Unfortunately, many contemporary railfan websites and discussions co-mingle the words "anthracite" and "culm" when discussing it as a fuel; but which in fact were very different from one another. While they both come from the same type of coal; it was screened (sized) anthracite that was used first in locomotives, and of which was produced by the coal mill or "breaker" and sorted by size using metal screens of various sizes.

Anthracite, is a type of coal. It has the highest content of carbon, and less impurities of the other types of coal: bituminous, sub-bituminous, lignite and peat. It burns cleanly and produces little smoke, and is the hardest of all the coals, therefore it takes longer to ignite and burn. Because it has the highest amount of carbon, it burns the hottest. Anthracite is prevalent in the Northeastern Pennsylvania region.

Culm waste, was the leftovers after breaking & sizing raw anthracite; as well as coal that had already been screened and sized but fractured as it was being handled and progressed down the chutes, it fell through the screens to the bottom of the breaker house and transported to the culm piles.

Here is an analogy: think of lumber;

.

2.3: Screened (or Sized) Anthracite

When it came to the early steam locomotives, they burned screened anthracite, not culm waste.

Screened coal (of any type) are sizes of coal that were able to pass or not pass through a specific sized sorting screen and constituted a maximum dimension. A large piece of coal would pass over the screen, which coal that fit through the sized opening would fall through.

The most commonly used sizes of screened anthracite coal for locomotives was "grate" (also known as "broken"); or "egg" which was the next size smaller.

It should be emphasized

that smaller sizes of coal under "egg", which are comprised of the following sizes (in diminishing order) of which were used for:

"stove" and

"chestnut" for domestic household stoves and heating:

Smaller sizes of coal such as: "pea", "buckwheat" and "rice" and "barley" (not shown); were used for industrial applications such as automatic stoker furnaces used for power generation and for use in electric arc furnaces to produce foamy slag.

Also not listed or show below is larger sized "steamboat" (4½" to 6") which was used for steamships. This size was not preferred for locomotive use neither.

|

|

|

| Coal Trade - 1920 |

sizes of screened coal: 12" tile, US

quarters: 15/16" diameter steamboat, rice and barley sizes not shown. |

.

.2.4: Parallel Development for the Anthracite Burner

|

According to Angus Sinclair's "Development of the Steam

Locomotive", 1907; there were a multitude of attempts to burn hard coal

in locomotives by locomotive designers and master mechanics. Each of these locomotive designers carried their own individual beliefs into what would work and why "the other guys design didn't work", but they all had one thing in common, and that was their desire to burn anthracite. While several of the designs produced never made it to widespread acceptance or production; some in part to their genuinely being unsuccessful from a technical or operational standpoint. Yet other designs did. But there was another reason why some designs did not find widespread acceptance. The following statement by Henry F. Colvin as quoted in Sinclair's book, and of which struck a chord with me:

So apparently, even if the locomotive performed acceptably; it was still subject to prejudice from "old timers" that turned their nose up at it. How little has changed in society, and how we continue to this day to pooh-pooh new ideas, designs, and ways of "doing things." Some of the designs that saw success sprung from the minds of Ross Winans, Zerah Colburn, and James Millholland. |

|

James Millholland became involved with the railroads at an early age, with the honor of working as an apprentice on Peter Cooper's "Tom Thumb" locomotive; which was the first American built locomotive to operate in the US and on a common carrier railroad.

Millholland had found so much pleasure in working with that one locomotive, that he dedicated his profession to railroad locomotives. He progressed his way up through the ranks of the mechanical forces until he eventually attained the position of railway master mechanic for the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad.

At this point in time, most locomotives were primarily fueled with wood or soft coal: bituminous, which was also available in Pennsylvania and neighboring West Virginia. It was here that Millholland realized, due to the plentiful supply of anthracite coal located in Northeast Pennsylvania; that he attempted to design a firebox capable of burning this plentiful but hard coal. Anthracite was so hard in fact, it was also called "stone coal".

Millholland would take wood burning locomotives that were either at or nearing the end of their service life, or had suffered various forms of firebox or boiler failure; and rebuild them with fireboxes of his designs.

Millholland's final design found that a wider and shorter firebox than normal was needed to burn this anthracite. As anthracite coal is harder than bituminous (soft) coal and by taking longer to burn, locomotives using anthracite therefore needed more "grate area" to sufficiently "fire" (generate steam) in the locomotive.

A simple comparison would be to wood species used for heating: softwoods such as pine or fir burned fast; while hardwoods such as maple, oak and ash burned slow.

Typical wood or bituminous (soft coal) burning fireboxes on locomotives of that time were long and narrow, and fit between the locomotive frame. Because anthracite burned slower, more was needed on the grate to produce enough heat to evaporate water to make steam. In stationary or very large objects like factory boilers and ship boilers, there was all the room that could be had for larger grates. But on locomotives it was a different story - they were small by comparison.

Millholland found if the firebox was enlarged and made wider (instead of long and narrow), anthracite could be burned in a mobile object such as railroad locomotives.

His plans were interrupted in January 1854, when the Philadelphia & Reading Shops burned, and his attention was needed on the rebuilding of those facilities. While he was eventually able to return his attention to converting the P & R's fleet of locomotives to coal burning; he never truly succeeded in developing a successful anthracite firebox. He eventually resigned his position in 1866. His successor would be one John E. Wootten.

.

2.6 - John E. Wootten & Using Anthracite Culm

John Wootten began his locomotive apprenticeship at the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1837. He left Baldwin Locomotive in 1845 to join a small shop operated by the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad.

Over the course of his career, he was appointed to Engineer

of

Machinery on February 1, 1866 when Millholland resigned; then he

advanced to Assistant Superintendent and Engineer

of Machinery

on February 2, 1871. On January 15, 1873 we was appointed to the

position of General Superintendent, and finally to General Manager on

January 10, 1877.

Like Millholland prior to him, Wootten was aware of the

plentiful amount of anthracite from the areas mines.

|

But even more prolific, was

anthracite waste or

"culm". Culm is the granular remnants and smaller pieces of coal after it had been broken and sized by screening for commercial use. As this culm was mostly small and irregularly sized, it was unwanted and contained up to 15% of foreign matter: slate, stone, sand, etc. Waste culm accounted for 18 to 20% of the production of anthracite coal for commercial use. And without a salable use, this culm found itself being piled next to or in close proximity to the breakers (the coal sizing mills) and in quantities to be considered a nuisance. As with most things unwanted, it was extremely cheap and in large abundance. In "large abundance" might very well be an understatement, as there were hundreds of veritable mountains of this unwanted culm scattered throughout Northeastern Pennsylvania. |

Anthracite Culm

|

.

2.7 - How Cheap was Culm?

Putting it into perspective for the era: circa 1890; the rates for coal was as follows: screened anthracite coal of the pea size cost 60 cents per gross ton, whereas anthracite culm was only 10 cents per gross ton.

This constituted a 50 cent per ton difference; however it should be noted that the pea anthracite and the culm was blended 1:1 for use in Erie locomotives. This brings the averaged amount to 35 cents a ton, allowing for a net savings of 25 cents per ton of coal. Other railroads used a blend of bituminous and anthracite culm. And when you have hundreds of locomotives burning hundreds to thousands of tons of coal a day; in using the culm, the cents add up into dollars.

Also, it should be known that culm to be used for locomotives was not used directly from the coal tip.

Culm was first washed to remove sand, shale and other small debris inherent from mining. But even with this washing step, it was still much more economical to use anthracite culm rather than the commercially sized coal that came from the production run.

.

2.8: Trial and Error and then Having to Break Old Habits

Culm consisted of sizes smaller than "buckwheat" coal, including "rice" "barley" & "pea"; with a small allowance for powders as well as larger sizes.

One of the issues that Wootten encountered in using culm as a locomotive fuel was by its being small and light, it would become airborne and lofted through the high draft fireboxes that were commonplace of that time for burning wood or larger chunks of anthracite coal. Or it would fall through the grates with wider openings that were used for that same wood or bituminous coal and wind up in the ash pan.

Thus Wootten began using a finer grate (smaller and thinner openings), and less (or softer) draft through the firebox. This combination had the effect of leaving the culm on the grate to burn completely; and when it did, the culm burned evenly and well.

The addition of a combustion chamber between the firebox and the flue sheet, furthered more complete combustion, allowing for greater heat transfer for increased efficiency and reducing soot and fuel wastage.

Yet, as soon as he had those problems solved, another issue cropped up. As the locomotive left the roundhouse and started working, the fire struggled.

The firemen of that time were used to piling the wood or larger chunks of coal thickly on the grates, which by nature of their size had ample space around the chunks for air to circulate through. This is also known as a "deep bed";

That method may have worked well for those large sizes of coal or wood as the voids around the fuel allowed air to filter through, but it did not work for anthracite culm.

Here is an analogy: think of a road made of rock and another road made of dirt. Here the gravel represents large sized anthracite, and the dirt represents culm, and water represents air. Water will drain through the rock because of the void spaces around the rocks; but puddles form on the dirt road, because the water has nowhere to drain to.

Well, Wootten learned the firemen were piling the anthracite culm into thick beds. Not enough air could rise through the bed of culm to support combustion and essentially they were smothering the fire or starving it. They took the air out of the fuel + air + heat equation or "fire triangle".

In their defense, this is what the firemen of that day had been trained for and used to. They were not used to any other methods.

.

2.9: Success = Large Grate Area, Thin Bed of Coals with Short Flame, Minimal Draft, Lower Brick Arch and a Combustion Chamber

|

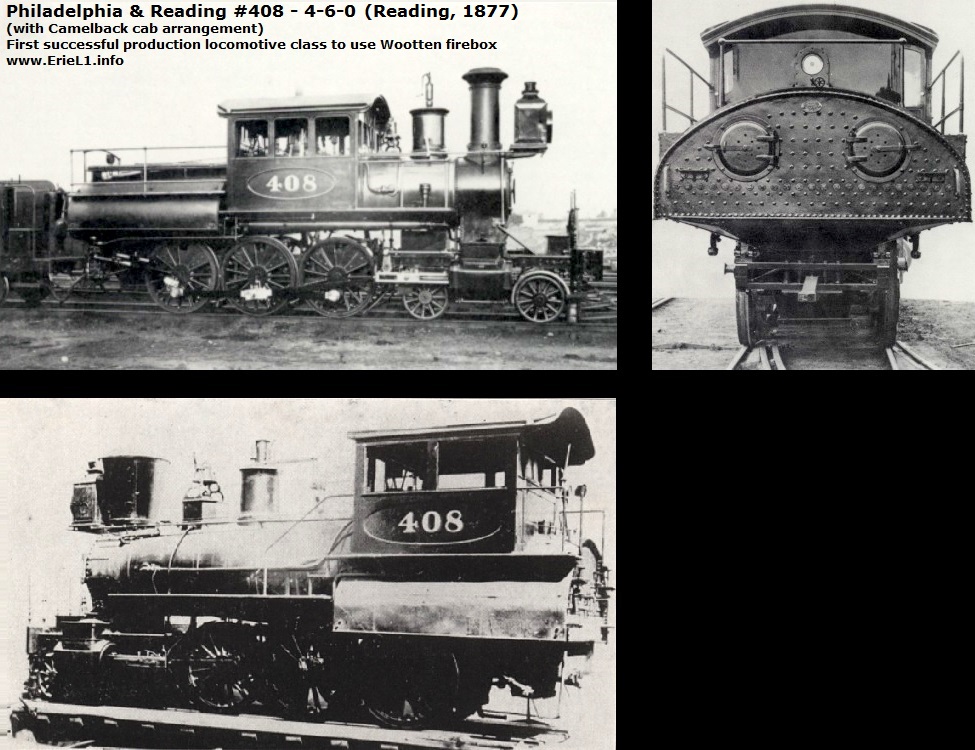

By dispensing with the previously established practices of firing by that method, and now specifying to the firemen that a thin bed of fuel and short flame; Wootten was able to make his firebox design meet the criteria required of being reliable, efficient, easy to maintain and as such; the heat output steady. And with these instructions, even a novice fireman could maintain it. And so in 1877, the firebox design fitted to P&R #408, and the new found firing practices meant Wootten had found the answer. In other words; anthracite culm / waste was now a suitable fuel for locomotives, where men of varying degrees of ability could satisfactorily achieve and maintain the fire fueled by culm, for producing a steady and reliable production of steam for all operating conditions; whether it flat and level or mountainous territory; the slow pulling of a heavy freight; or a fast paced running of a passenger train on a tight schedule. This new "fuel" equated into a savings of $2000 per locomotive per year. And in 1883, the Philadelphia & Reading rostered 171 locomotives with the Wootten firebox. That equaled $378,000 per annum in saved fuel costs. Obviously, the corporate higher ups and the shareholders were pleased. The Wootten firebox also changed the weight distribution on the locomotive chassis, and due to the increased size of the firebox, meant the firebox needed to be mounted as far over the rearmost driving wheels as possible for support; and to avoid Colburn's issue of a excessively long drawbar connecting the engine and tender. This (mostly) precluded the use of trailing trucks on the frame to support the firebox with smaller diameter wheels common to freight service; but it increased tractive effort as more weight was directly on the drive wheels. |

|

So revolutionary was the design, that sister locomotive P&R #412 was shipped overseas to be demonstrated. The locomotive won the silver medal at the Exposition Universalle de 1878 (Paris, France); after demonstrating throughout Europe and proving successful.

The Wootten firebox design also was awarded the following medals: the John Scott medal (bronze) awarded by the City of Philadelphia and by recommendation of the Franklin Institute; and in 1883, the Philadelphia & Reading won an award for "best locomotive meeting important new principals" by the National Exposition of Railway Appliances, held in Chicago, Illinois.

At the end of 1895, there were about 800 locomotives in service with Wootten's firebox design. By 1925, there were approximately 3,500 to 4,000 locomotives in service with Wootten's firebox.

.

2.10: Both Sides of the Coin

There was another positive attribute to be said for Wootten's firebox design: it burned bituminous coal equally as well as anthracite.

When the price of anthracite and with it culm, rose due to both growing popularity as well as due to coal miners strikes; the railroads began using either a bituminous / anthracite culm blend, or straight bituminous.

Obviously, because bituminous burned faster, not so much coal was needed on the grates, so grate boxes or frames were fabricated which reduced the grate firing area confining the coal to the centered middle of the firebox.

Bituminous fireboxes however, because of their smaller square footage of grate area; could not be fired on anthracite or anthracite culm.

2.11: But Not Everyone was Happy

But, this oversized "Wootten" firebox took up most if not all of the space on the rear of the boiler or "backhead" where the cab was normally placed. This position of the firebox also presented the issue of the cab floor now being higher than the standard tender deck height.

|

Also, due

to the broad nature of the firebox, the engineer could not see around

the firebox as he would encounter with a normal rear mounted cab. If the cab were to be mounted on top of the Wootten firebox, the crew would be in effect sitting on top of the firebox. Also as a result of this placement, the cab would be raised higher than before, and would necessitate that some of the tunnels of that time to be raised. This of course was not an option. As we can see by the bottom left image, the Philadelphia & Reading even contemplated this rear cab Wootten firebox arrangement. Ungainly to say the least! So, necessity dictated the locomotive cab be located towards the center of the boiler in front of the firebox instead of on the rear as normal; sort of like a horse's saddle. Hence the modern "camelback" locomotive was born. This placement of the cab allowed the engineer to retain access to the entire length of the boiler, and likewise from the front or the rear steps to maintain the appliances and bearings. The fireman would remain to the rear of the firebox to feed the fuel as customary, and tenders with high deck heights were constructed for use with camelback locomotives. With the engineer in the cab to operate the locomotive; this would mean the engineer and the fireman would be out of instant communication with one another. This would be one of the serious concerns brought about by opponents of the camelbacks. At first, these were old timers set in their ways. In some cases, a speaking tube (like those used on ships) would be answer. |

.

2.12 - A Trailing Truck - To Be or Not To Be?

As mentioned, the weight of the large firebox box and resultant weight distribution of the locomotive required the firebox to be placed over as much of the driving wheels as possible.

And with the smaller diameter wheels common to freight locomotives, is why Camelbacks are predominantly seen in wheel arrangements without trailing trucks, and where the rear driving wheels could carry the full weight of the Wootten firebox.

These wheel arrangements were mostly comprised of (but not limited to) those listed:

And, there were road engines as well, such as:

Exceptions to this rule of course, were high drivered - high speed passenger locomotives such as:

.

2.13 - Whyte Notation

also called the "wheel arrangement"

In the United States and United Kingdom, wheel arrangements of locomotives are described by the leading or pony wheels (in any), the powered drive wheels and the trailing truck (in any).

This system was devised by Frederick M. Whyte, and came into use in the early Twentieth Century. Geared steam locomotives, electric locomotives as well as diesel electric and gasoline mechanical locomotives do not use the Whyte notation. These are classified by their model and the number of axles and trucks, and whether those axles are powered or unpowered.

The Whyte Notation counts from left to right (with left being the front of the locomotive); the number of idle leading wheels (not the axles as in other systems), then the number of powered driving wheels, and finally the number of idle trailing wheels, with these numbers being separated by hyphens.

For example, a locomotive with four wheels (on two axles) leading in front, then six driving wheels (on three axles) and then two wheels (one axle) trailing is classified as a 4-6-2 locomotive, and is commonly known as a "Pacific".

A small switching locomotive with no leading wheels, (four driving wheels on two axles), and no trailing wheels, is notated as an 0-4-0.

With this system being explained and returning to camelback locomotive design.

.2.14 - Camelbacks: Who Used Them?

Returning to camelback locomotive design, as a result of this large firebox on the rear of the locomotive, the cab was relocated to middle of the boiler and such locomotives became known as "Camelbacks" or "Mother Hubbards".

The camelback design worked very well for many of the railroads located in the Northeastern United States that either operated their lines through the "hard coal country" of Pennsylvania, or those that received coal from Pennsylvania for local coal suppliers.

There were many and by no means should this be considered a complete list:

|

|

- Union Pacific

- Southern Pacific

- Santa Fe

- Canadian Pacific

|

When

locomotive design practice evolved to accommodate rear mounted cabs on

locomotives with Wootten fireboxes, these cabs lacked the usual doors

on

the front wall. This is perfectly illustrated by the image

of the rebuilt Erie L1 at right. Without a doubt, this lack of front doors on the cab hindered the engineer and / or fireman from their basic maintenance duties such as but not limited to: filling the sand domes; adjusting valves; cleaning the bell; oiling and maintaining the steam generator for locomotive lighting; all of which are along the top of the locomotive as well as lubricating / maintaining the air pumps for the brakes, which were mounted along the side of the locomotive. The engineer or fireman (or both) would have to climb down at the rear cab / tender access steps, walk to the front of the locomotive, then climb back up to boiler walkway; instead of exiting directly from the front of the cab as had been the practice. |

Erie Railroad #2600

after Baldwin rebuild - 1921

authors collection |

And you thought the engineer sat on his seat and the fireman leaned on his shovel all day!

It should be noted - this trend away from camelbacks was due in part to safety. But as I will cover in a later chapter, camelbacks were not universally banned by the Interstate Commerce Commission or any other federal agency, by locomotive employees unions, et cetera; despite the popular misconception they have been.

Then if the camelbacks weren't outlawed, what did cause the trend away from camelback type locomotive design? What usually talks the loudest? Money!

Just as in the beginning when anthracite was cheaper than bituminous and culm was the cheapest of anthracite, anthracite rose in price due to its desirability of being clean burning and low dust; which made it a favorable fuel for home heating. This led anthracite coal breakers to be more judicious in what they dumped as culm (waste), as well as the resulting increased prices from increased demand.

Added to this increase in the price of anthracite, was the Anthracite Coal Miners strike of May - October 1902.

That led locomotive manufacturers to revert to firebox designs that burned the now cheaper bituminous coal that did in camelbacks. And as stated previously; a Wootten firebox is just as capable and efficient at burning bituminous coal as it could culm, so existing locomotives with Wootten fireboxes could run either.

This is to say nothing of the development of the diesel-electric locomotive in the 1930's; first as switchers, then in increasing quantities of road locomotives; which pretty much supplanted steam as a locomotive power on the whole by the 1950's.

.

2.16 - Crew

Comfort in Comparison to Another Type of "Camelback"

And the following comparison might be somewhat of a stretch, but the camelback locomotive would not be the only widely successful locomotive design where performance and reliability was exceptional, but its shortcomings were crew ergonomics or comfort. What locomotive is this you ask?

|

None other than the

Pennsylvania Railroad GG1. Another center cab design, it could

in a way, be considered a "camelback electric

locomotive". Access to the locomotive cab was via a rather tall vertical climb. And once inside, both the engineers and firemans stations were notably cramped. There was a small passageway connecting the two sides, but with floor to ceiling banks of controls and gauges, it made it visually difficult to see from one side to the other from either station. I can personally say I have been in the cab of a GG1. Even though I'm 5' 9" (and not very svelte), it would a very tight squeeze for even someone of smaller stature. Then there is all that electrical energy being converted from AC to DC, the transformers, and traction motors; it all gave off heat. Add to this the presence of an oil fired steam boiler in the cab which was used to generate steam heat for the passenger cars. No doubt it made for some uncomfortable crew conditions, especially on long distance trips. But undoubtedly, the GG1's were in fact a successful locomotive design and many were built. There were thousands of center-cab diesel locomotives built (especially by General Electric) so having the cab located in or towards the center of the locomotive, so the center placed cab was not a disqualifying factor in and of itself. |

|

Again, as I and others have pointed out, despite the outcry over steam powered camelbacks, they were in fact; successful as well.

.

Chapter 3:

What is Mallet Compounding?

|

The three Erie L1 0-8-8-0 locomotives were the only

articulated Mallet Camelbacks

built, and they would also have the distinction of being the Erie

Railroads' first

"Mallet"

locomotive, as well as their first articulated locomotive. For the record, the correct pronunciation is mal-LAY, after Anatole Mallet, who was a Swiss mechanical engineer and consultant. However, and all too frequently here in the States, it is often pronounced mal-LUTT (like the hammer). You may say ta-MAY-to, I may say toe-MAH-toe; but mal-LAY is the correct pronunciation in this case. Mallet Compounding is a system designed to utilize steam twice, instead of once (also known as simple expansion). Compounding thereby extracts additional energy or force out of steam, making the engine more efficient. Therefore in such an engine that steam from a boiler is used first in high pressure (hp) cylinders, then piped partially expanded to a second set of low pressure (lp) cylinders for final expansion. Compound: |

|

This compounding method is a very efficient way to use the steam twice for large multi-cylinder locomotives, as well as marine vessels and stationary steam locomotives used for electrical generation or pumping; and where single expansion would have used up the steam capacity too quickly.

.

3.1 - The Intercepting Valve

But there was another feature inherent to the design of Mallet Compounding; the intercepting valve.

This valve, located in the left side high pressure cylinder, allowed the engineer to admit high pressure steam into the low pressure system. This was especially useful when starting the locomotive and train on a grade. Not often, but when required; a train may have had to stop while already on the the incline. If the train was heavy enough, even an L1 could have issues getting moving again with all that tonnage. By admitting high pressure steam into the low pressure system, gave the front cylinders more power, and having more power assisted in getting the train started moving again.

But, there was a drawback to using this intercepting valve: in its "simple" setting where it diverted high pressure steam to the low pressure cylinders, it used up the steam pressure in the boiler at a quicker rate.

Therefore

it only was used absolutely when needed, and was not

intended to be used in

normal operation. Westing referencing to this in the Erie Power

book (as you will read later).

"The

L1's could operate as simple or single expansion locomotives, if

desired, by use of an intercepting valve. This was a feature on Mallets

and arranged for live, or high-pressure steam to be fed to all

cylinders, thereby, increasing tractive force considerably. On

the

other hand it had the effect of speedily draining the boiler of

steam"...

Westing clearly states simple expansion was an option "if

desired".. Nowhere does he state that it operated in this simple

expansion mode all the time.

Unfortunately, most railfans only read the second half of the chapter. Perhaps Westing could have worded it better, but it is still very clear that when read carefully and thoroughly, the boiler was only "speedily drained" in the simple expansion mode of the intercepting valve, not all the time during regular compound operation.

And this effect was known long before the L1's. It is inherent to the design of the Compound Mallet with intercepting valves. (For the record, a Compound Mallet could be built without an intercepting valve, and it would be useful in a normal capacity just the same.

Where I will pick apart Westing's description: "live, or high pressure steam". Live steam is under pressure, any pressure; whether it be 215 psi or 50 psi or 5 psi. Under any pressure, it is "live" steam. Only once it is exhausted and not under pressure, is it considered "dead" steam.

You can have a 1 hp single cylinder steam engine that operates at 5 psi.. like the little alcohol powered novelty toy engines that are sold. If steam is under pressure, it's live steam. It's still alive partially expanded from 215 to 50 psi. Only when fully expanded and no longer under pressure, is it dead. Like electricity: any voltage in a wire is live voltage. Zero voltage is dead.

So, he should have stated "live, or pressurized steam". Other than that, and quite obviously, this Mallet Compounding design was successful, as these L1 locomotives served not only the Erie Railroad reliably for 23 years for but before then, as well as after; on many other articulated Mallet compound locomotives that were built for several different railroads.

.

3.2 - Articulated ≠ Compounding

It should be kept in mind that an articulated locomotive does not equate to Mallet Compounding. Articulated denotes the type of frame or chassis, and from that you had Simple Articulated or Mallet Compounding Articulated.

As such, not all articulated steam locomotives need be of the Mallet Compound type. A significant number of articulated locomotives were built were of the simple expansion type. And plenty of rigid frame locomotives utilized compounding, but were not of the Mallet Compounding design.

Commencing in the late 1920's, saw the advent of successful, high efficiency superheating, feedwater heating, improved metallurgy and manufacturing practices for higher boiler pressures, mechanical coal stokers, etc; which led locomotive builders away from the compound Mallet locomotive design, but the design did not become extinct.

The Chesapeake & Ohio Railway ordered twenty-five H-6 class 2-6-6-2 in 1940 for use as low-speed coal mine shuttles between the mines and classification railyard in Russell, Kentucky. Ten locomotives were completed before the order was cancelled with the final locomotive delivered in 1949. It is these ten locomotives that would carry the distinction of being the last compound Mallets constructed.

If any class of service to which type was better suited at than the other; compound Mallets seemed to be preferred for low speed, heavy drags and pushing; whilst simple expansion types were predominantly used for higher speeds over longer distances; but this is not set in stone.

A short, very incomplete list of the popularly known types of articulated locomotives, both Mallet compound and simple:

| Mallet (Compound) Locomotives |

Simple Expansion Locomotives |

||||||||

| year built | railroad | class | wheel arrangement | notes | year built | railroad | class | wheel arrangement | |

| 1904 | Baltimore

& Ohio |

2400

"Old Maud" |

0-6-6-0 |

first Mallet Articulated | 1910 | Southern Pacific | MC-2, MC-4, MC-6 | 2-8-8-2 | |

| 1907 | Erie | L1 | 0-8-8-0 | 1936 | Norfolk & Western | A | 2-6-6-4 | ||

| 1910 | Norfolk & Western | Y | 2-8-8-2 | 1936 | Union Pacific | CSA-1/2; 4664 "Challenger" | 4-6-6-4 | ||

| 1912 | Pennsylvania | CC1 | 0-8-8-0 | 1941 | Duluth, Missabe & Iron Range | M-3 / M-4 | 2-8-8-4 | ||

| 1918 | Virginian | AE | 2-10-10-2 | 1941 | Union Pacific | 4000 "Big Boy" | 4-8-8-4 | ||

| 1940 | Chesapeake & Ohio | H-6 | 2-6-6-2 | last Mallets built | |||||

Chapter 4:

Why the need for Articulation?

"It

don't mean a thing, if you ain't got that swing - doo wah - doo wah -

doo wah!"

.

4.1 - What is Articulation?

|

An articulated locomotive is a steam locomotive with an engine unit that can move independently of the main frame. The purpose of articulated locomotives was to provide additional drive wheels (which in turn added tractive effort), but avoid the drawbacks of the lengthening the wheel base as would on a rigid frame locomotive; of which would limit the locations the locomotive could be operated at, that being track profiles with sharp curvature, whether they be mainlines or mountain logging railways. More axles meant a longer wheel base, which equated to the shallower curve that particular locomotive could be operated on. The most axles ever incorporated into a single rigid frame in US locomotive design, was the 9000 class 4-12-2 for the Union Pacific Railroad. The most axles incorporated into an articulated locomotive set, is four: 0-8-8-0, 2-8-8-2 and 4-8-8-4, as well as the 2-8-8-8-2 and 2-8-8-8-4 triplexes. Another benefit of the articulating locomotive, is that it allowed one large locomotive to replace multiple smaller locomotives, which would have also meant their needing a separate engineer and fireman for each locomotive. A single articulating locomotive also eliminated the associated cost for maintenance and upkeep of those multiple locomotives. The articulated locomotive is designed to allow the front set of driving wheels and its mechanisms be mounted to a frame that pivots or "swings" to the left and right (on the horizontal plane), separately and independently from wheels and machinery on the main frame. On an articulated locomotive, each group of these drive wheels with their cylinders, drive rods and other associated components; is called an "engine". Therefore, articulated locomotives have a front engine and a rear engine. In the case of the triplexes; there was a front, a middle and a rear engine. So, by dividing up the axles into two groups (or even three groups as done on the Erie & Virginian Triplexes) allowed the locomotive to be operated on sharper curves than a single long rigid frame locomotive could. This was especially useful where numerous curves existed along a rail line; such as those encountered on mountainous territory like the Erie, or on logging operations in the Pacific Northwest. |

|

leading or pony truck - powered drive wheels - powered drive wheels - trailing truck

As such is the case of the Erie Triplex, those were 2-8-8-8-2: a two wheel lead or "pony" truck, three engines of eight drive wheels, and a two wheel trailing truck; or in the case of the Virginian Triplex 2-8-8-8-4, denotes two wheel leading truck, three engines of eight drive wheels and a four wheel trailing truck

By comparison, those Whyte notation examples of rigid wheelbase locomotives such as the 0-4-0 through the 4-12-2; the single center number represents the powered drive wheels.

The following table represents the wheel arrangements of known standard gauge articulated (simple and compound) locomotives built and operated in the United States.

| Whyte Notation | Whyte Name | user railroads |

| 0-4-4-0 | D&RGW | |

| 2-4-4-2 | "Little River" |

Columbia River Belt Line |

| 0-6-6-0 | "Two six-coupled" | B&O, KCS, WM, NYC, WM |

| 2-6-6-0 | "Denver & Salt Lake" | D&SL |

| 2-6-8-0 | GN, AGS, B&O | |

| 2-6-6-2 | "Mallet Mogul" | GN, C&O, WM, NdeM |

| 2-6-6-4 | "H4-A" also "Norfolk & Western" | N&W, P&WV, SAL, B&O |

| 2-6-6-6 | "Allegheny" | C&O, VGN |

| 4-6-6-2 | "Cab Forward" | SP |

| 4-6-6-4 | "Challenger" | UP, Clinchfield, NP, D&H, D&RGW, SP&S, WM, WP |

| 0-8-8-0 | "Angus" | Erie, PRR, NYC |

| 2-8-8-0 | "Consolidation Mallet" or "Bull Moose" | PRR, GN, UP, RDG, B&O, KCS, AT&SF |

| 2-8-8-2 | "Chesapeake" | N&W, SP, UP, OR&N, Southern, VGN, GN, Clinchfield, D&RGW, RDG, WM, MP, SL&SF, DM&IR, PRR |

| 2-8-8-4 | "Yellowstone" | NP, SP, DM&IR, D&RGW |

| 4-8-8-2 | "Cab Forward" | SP |

| 4-8-8-4 | "Big Boy" (originally Wasatch) | UP |

| 2-10-10-2 | "Virginian" "3000 class" | AT&SF, VGN |

| 2-8-8-8-2 | "Triplex" | Erie |

| 2-8-8-8-4 | "Triplex" | VGN |

abbreviations: AGS = Alabama Great Southern; AT&SF = Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe; B&O = Baltimore & Ohio; C&O = Chesapeake & Ohio; D&H = Delaware & Hudson DM&IR = Duluth, Missabe & Iron Range; D&RGW = Denver, Rio Grande & Western; D&SL = Denver & Salt Lake; GN = Great Northern; KCS = Kansas City southern: MP = Missouri Pacific; NdeM = Nuevo de Mexico; NP = Northern Pacific; N&W = Norfolk & Western; NYC = New York Central; OR&N = Oregon Railway & Navigation; PRR = Pennsylvania RR; P&WV = Pittsburgh & West Virginia; RDG = Reading; SAL = Seaboard Air Lines; SL&SF = St Louis & San Francisco SP = Southern Pacific; UP = Union Pacific; VGN = Virginian; WM = Western Maryland; WP = Western Pacific |

||

Before concluding this chapter, it should also be taken into account that some rigid frame duplex locomotives, like the 4-4-4-4, 4-6-4-4, 4-4-6-4 or 6-4-4-6; while they have two groups of drive wheels and two sets of cylinders similar to an articulated locomotive, they were not articulated, and consisted of a single rigid frame containing both sets of drive wheels.

.

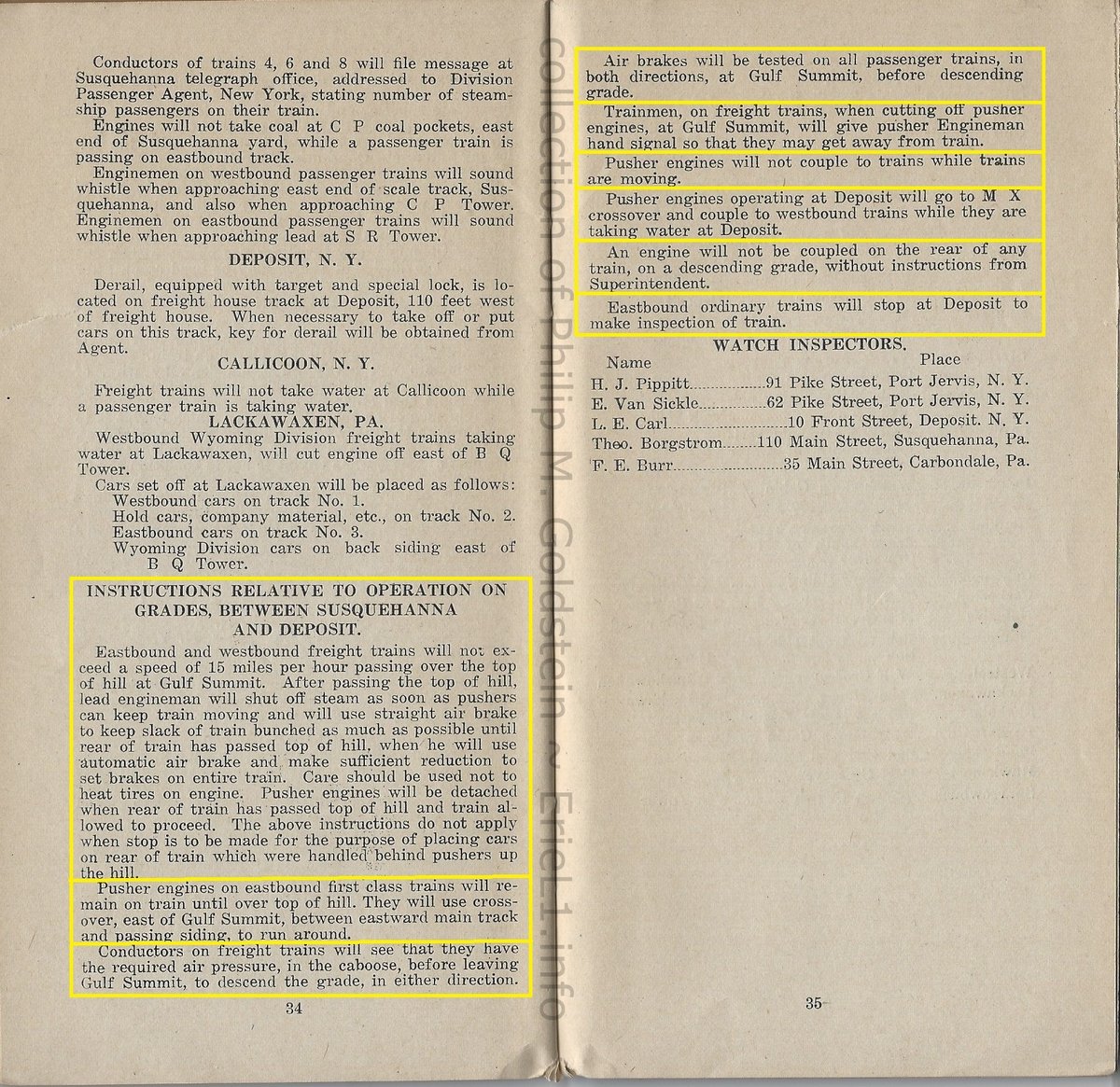

| The L1's were designed from the very beginning for, and

assigned to "pusher service"; that is, they

assisted by pushing heavy freight trains over Gulf Summit on the

Pennsylvania / New York border. The Gulf Summit was not simply straight up and over, it had numerous curves and reverse curves on both sides of the summit. These freight trains normally had one or two locomotives on the head end; which was sufficient for most of the route, which was fairly level along the banks of the Susquehanna River and the West Branch of the Delaware River. But to go over the steep Gulf Summit, those two locomotives were inadequate. While placing a third or even fourth locomotive at the head end of the train would provide more pulling power, but with the weight of the train pulling backwards downhill due to gravity, the train could then incur a pulled draft gear (the bar that holds the coupler under the freight car) or a broken coupler knuckle. This would make the train "break" into two parts, and even with the recent advent of air brakes, this was not something a railroad wanted to happen on steep grades. Pusher locomotives were therefore added to the rear of the trains if needed at Susquehanna, PA for the eastward trains; and at Deposit, NY for westbound trains to push them up and over Gulf Summit. Pushing relieved the tension and strain on the draft gear and coupler knuckles throughout the train length, as well as alleviated slack action which is also known as run in / run out. |

|

and the P1 Class Triplex "Matt H. Shay" for direct comparison

.

We were fortunate that a very nice history concerning the construction and reconstruction of these locomotives is contained in the 1970 book: "Erie Power" by Fred Westing & Alvin Staufer (Staufer Publishing, 1970). You will find these pages under the chapter of Erie Mallets, pages 198 through 215.

For the sake of thoroughness, I have scanned and reproduced the pages here on the chapter of Erie Mallets for reference. I highly recommended purchasing a copy of the book, if for nothing else, the great action photographs. The book can be found for very reasonable amounts on most used book websites, internet auctions and shopping sites.

Until my own research, and for the longest time; I pretty much regarded this historical accounting as gospel - and many others did as well. After all, it was published 50 some odd years ago and within a generation or two of the locomotives operation. There also was not much available open source to the average railfan to dispute.

.

6.1 - Unfortunately, it contains some inaccuracies and indistinct statements

However, as original documents and photographs surfaced during my research, I uncovered several discrepancies and / or indistinct statements; some major, others merely cosmetic.

Insomuch, learning of these inaccuracies was kind of disappointing, as I have always revered the older publications (like the Staufer "Power" books) to be the last word and authoritative.

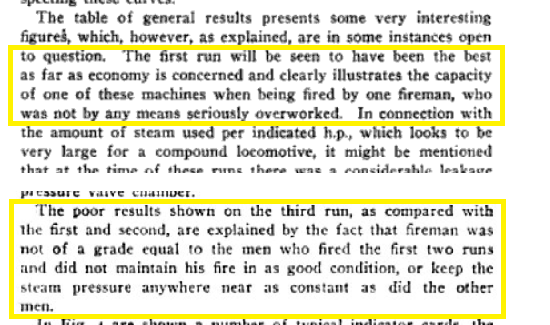

It now appears that in his composition, Mr. Westing may have allowed a little too much personal opinion sway his judgment on overall performance or in captions for the images. In particular are his conclusions regarding the performance testing conducted by the Erie Railroad and Cornell University in 1907, and of which the explanations for some of the lackluster results.

The test results are defined in great detail, and explain the reasons behind the results of the "third" test, and how it skewed and lowered the average performance numbers on the whole. These explanations can be read in The Erie Test - 1907 and the Cullen / Gridley - Cornell U Thesis - 1908 chapters later in this website.

I have also included the last few pages of that chapter which pertain to the experimental Erie 2-6-8-0 Mallet and the Erie Triplex 2-8-8-8-2 "Matt H. Shay", and as the images of the Erie L1 both as built and as reconstructed by Baldwin Locomotive Works were on those pages, even though the text was for a different locomotive entirely.

I have annotated the scanned pages with those differences I found or highlighted details that reinforce my disproving of common myth and misinformation.

Please note, the following pages have been digitized for reader convenience, reference and review under the Fair Use provision of the US Copyright Office and no such infringement should be inferred by the use of said documents for commentary, criticism, and research as discussed below. Original copyright remains with original author (Frederick Westing) and publisher (Alvin Staufer / Staufer Publishing).

|

|

|

| . | |

|

.

.. |

|

|

|

|

1) "two fire doors to facilitate spreading coal" and; "if you wanted to use two fireman" |

3) dynamometer car rated to 70,000 lbs tractive force, but the L1's were rated at 94,000 lbs.! |

| . | |

|

|

|

| . | |

|

|

The wooden pushing beams were installed from the beginning. They are seen in the erecting drawings, builders photographs (including the E. DeGolyer construction image on p.202 above) as well as images in Railroad Gazette (p.174). |

| . | |

|

|

|

While this highlighted text has nothing to do with the Erie L1 Class; it does show how misinformed present day railfans assume that when the coal and water was used up in the Triplex, it lost tractive effort. Which as read here, was not the case as it clearly states that factor was taken into account in the design! Not to mention the locomotive being used on short runs and replenished more quickly, the coal and water was not run down as other distance hauling locomotives would be. |

|

| . | |

|

|

|

| . |

Table of comparative statistics among the various Erie Mallets (L1 class highlighted). |

| . | |

|

|

|

| . | |

|

|

|

|

"Erie Power" |

|

| .. . . . |

|

Camelback locomotives already have erroneous information swirling about them. The Erie L1 class Mallets appear to be doubly damned in regards to misinformation.

Not only do a lot of railfans not understand how they worked, but also do not understand what they were designed for and the work they performed; why only three were built; and when they were designed, they were cutting edge technology of that era.

It is all too easy for todays generation of railroad enthusiasts to look at the culmination of super-power steam locomotives of the 1940's through 1950's; and then erroneously think these Erie L1's weren't good enough, simply by comparison to those latter designs.

Some of these misconceptions arise from the Staufer / Westing chapter of Erie Mallets in "Erie Power"; while others come from present day misunderstandings and myths posted in Facebook Groups by the misinformed; or worse, the less-than-minimally informed. You know the types: "If I didn't see it, it didn't happen" juxtaposed by the "I read it on the internet, it must be true!" types.

"The Erie 0-8-8-0 wasn't the biggest - the 'Big Boy' was."

"World's Largest Locomotive"In early 2024, I received an email from a railfan, stating the Erie L1 wasn't the largest locomotive ever built - it was the Union Pacific's "Big Boy". The tone of correspondence was rather indignant, I may add.

First, I had to take a minute and re-read his email to make sure I was not misreading it. When I realized I had not; the next few moments I took were to come out of a state of shock over the tone of indignancy. Only then, could I take a few minutes to actually explain the "Big Boy" wasn't built until 1941, and these L1's were built in 1907, and when they were built 34 years before the "Big Boy"; the L1's were the largest steam locomotive built - at that time.

And even then, if you were take all the steam power built up to 1954 (the year the last steam locomotive was built for general service in the United States); the "Big Boys" were still not the undisputed "largest" by several units of measurement. referencing the page: "The Largest Steam Locomotives" on steamlocomotive.com website:

.

Needless to say, despite my reply; I am still awaiting a response from this person (but I'm not holding my breath...)

There are those that will counter with that the C&O M1 was not a true steam locomotive, it was a steam turbine; as was the N&W "Jawn Henry". But both were coal fired, had boilers and ran on steam. The PRR S2 was a steam turbine locomotive, and no one ever questions whether or not that was a steam locomotive.

I am not anti-"Big Boy" or anti-Union Pacific in the least; nor can I say with honestly that I favor eastern railroads over western; pre-superpower designs over superpower; experimental locomotives vs. those commercially produced and sold, etc. I am not an Erie Railroad historian or even an Erie "buff", nor can I consider the Erie my "favorite" railroad. That honor belongs to the rail-marine operations of the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal.

But, I can say very enthusiastically that the Erie L1 is my favorite locomotive design.

An analogy would be like a "car guy" trying to compare a 1920's Model T to a 1950 Cadillac. Of course the Caddy was bigger, more powerful, much faster, heavier, could go further, and do so more comfortably! Yeah, they both had four wheels and ran on gasoline, but that is about where the similarities end. Hell, one shouldn't even compare a Model 'T' to a Model 'A' for that matter because of the advancements made in automobiles in that 20 year period.

As of her restoration to operation in 2019, the Union Pacific 4014 "Big Boy" is the largest steam locomotive currently in operation in the United States.

But she is not by any means, the largest steam locomotive "ever built" and certainly not before 1941. Not here in the United States, and certainly not in other places around the globe.

.

.

"They Were So Big - The Cabs Struck Each Other"

.

Here is yet another head-shakingly unbelievable statement that I came across on the internet in November 2024.

Posted to a Youtube video of an O scale model of an Erie 0-8-8-0 Camelback being demonstrated; one of the commenters, (inhereafter referred to as the "defendant") made the following comment to the video.

"Here is another fact for

you: The Angus boilers were so big

that when two Angus passed one another, the cabs struck each other.

There were a number of engineers and fireman killed."

.

How does one even counter a so blatantly erroneous and false statement? The fact that this claim is so egregious; angers me greatly.

Defense: Motion to dismiss your honor.

Motion denied.

Prosecution; present your case.

Good day your honor, members of the jury. The

Prosecution

will prove that the defendant has no idea what he is talking about.

.

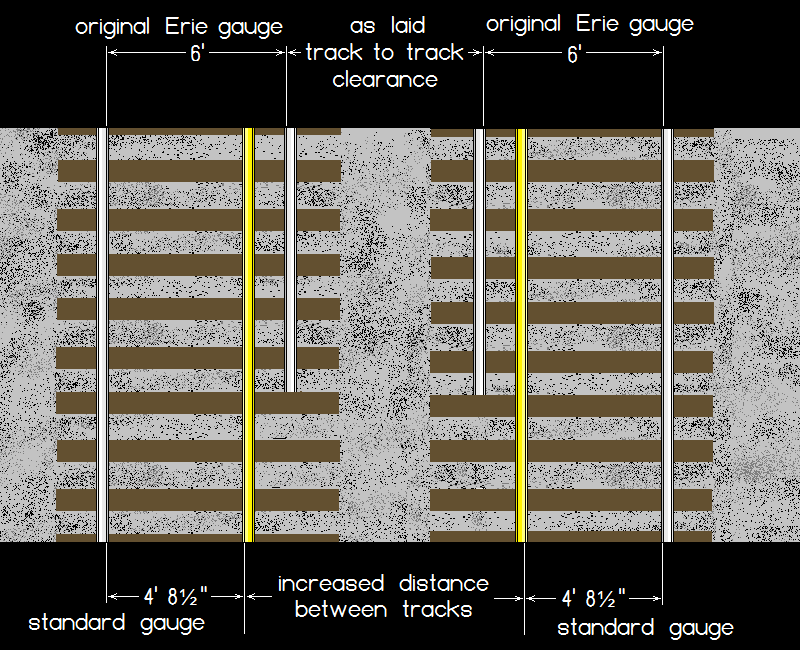

8.1 - Exhibit A: The Erie Railroad had Broad Gauge Clearances with Standard Gauge Operations:

The Erie Railroad when originally built in 1832, was constructed to broad gauge; that is 6 feet between the rails and not the present 4' 8½" standard gauge. This would include the specific route the 0-8-8-0 Angus' operated on, between Binghamton and Port Jervis.

As such, locomotives and rolling stock that were built for the Erie Railroad in this broad gauge era, were somewhat oversized by comparison to standard gauge equipment.

When the Erie re-gauged its trackage to meet the then newly adopted U.S. standard of 4' 8½" in 1880; track clearances actually increased by default.

This is because a third running rail was installed in-board by 15½"- which had the effect of leaving either more room between tracks (on two or multiple track main lines), or more room to tunnel walls and trackside objects such as signals, walls, stations etc.

But the equipment, having been manufactured for standard gauge; was inherently narrower by original construction than the original Erie equipment. Reference Alleghany County Historical Society:

| New York

Tribune - January 4, 1879 Erie's Narrow Gauge The Laying of the Third Rail. Advantages of the New Gauge. In April last of the Erie Railway

reorganized, and under the new

management the familiar name was changed to New York, Lake Erie and

Western Railroad. But the new management made other changes besides

that of name.

The most important of these has been change of the gauge of the road, which has been accomplished by the laying of a third rail. This work was begun in 1876, when the alteration was made on the Buffalo, and a part of the Susquehanna Division, so that narrow-gauge cars of the Lehigh Valley Line were run from Philadelphia through to Buffalo on the Erie Road from Waverly. Last summer the laying of the third rail was continued to Binghamton, connection being there made with Albany by the Susquehanna Railroad (the Albany & Susquehanna RR; to become the Delaware & Hudson Railroad; PMG). The work was completed last when the additional rail was finally laid to Jersey City, and yesterday the first train passed over to Port Jervis, the end of the Eastern Division. Hereafter it will be in constant use." and:

"We have ordered thirty new engines, which are being made in Patterson [sic]*, and 3,000 new freight cars. The present rolling-stock will not be altered but will be replaced as fast as worn out by those of narrow gauge." (* "Patterson" refers to Paterson, NJ; which was home to Cooke Locomotive & Machine Works as well as Rogers Locomotive Works and Grant Locomotive; all of which were located in Paterson, NJ; PMG) |

|

Another reason for the decision on moving the center-most rails and not the outer rails, is that already existing station platforms located on the outside (field side) of the rails would have to be extended, which of course would bear the greater expense.

As such; the rights of way, bridges, tunnels and other physical infrastructure of the Erie, were constructed to accommodate the original Erie 6 foot gauge; and were now wider than needed what with the narrower equipment of standard gauge.

But, as I have stated in Chapter 8.1 above; the L1's would have had to go over the Delaware & Hudson Railroad trackage first, which had NOT been built to wide gauge standards like the Erie Railroad had been.

Therefore, if the L1's did not collide with anything while in transit on the Delaware & Hudson; more likely than not they were not going to collide with anything on the Erie.

But I will admit, this is circumstantial evidence, and that is insufficient to prove my case.

.

8.2

- Exhibit B: Firemen on Camelbacks Were Getting Killed in the Cab

Collisions? Wait. What? Firemen Weren't in the Cab!

Here is yet another point (presented in two parts) to disprove the "defendant's" statement:

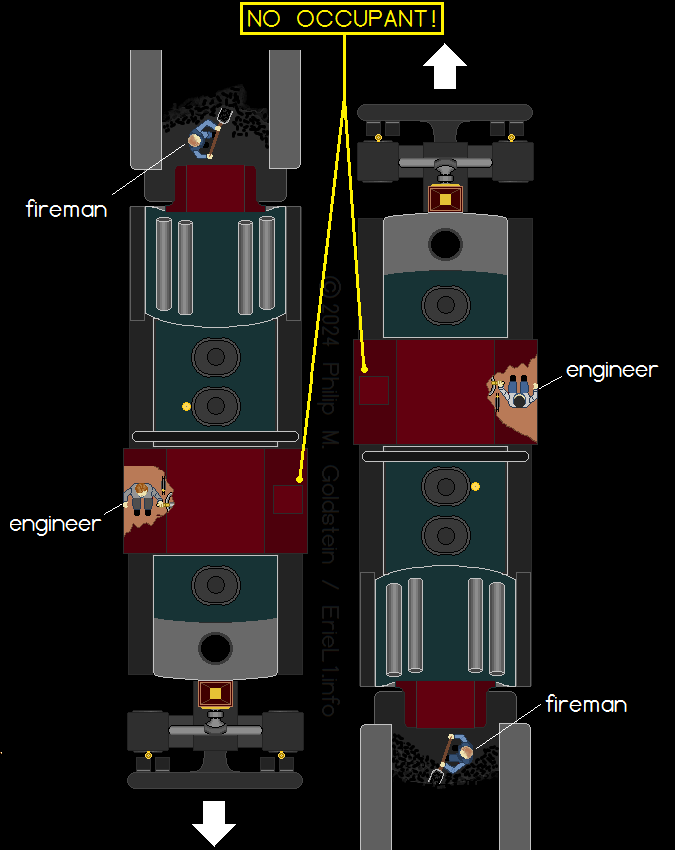

|

|

|

The United States railroad industry (and other railroads

around the world) have

what are referred to as "loading gauges". In the US, Class 1 railroad main line loading gauges began to be standardized in 1886; an were usually published annually; and as seen at right this was the diagram for the year of 1907 - the same year the L1's were constructed. This loading gauge did not apply to narrow or broad gauge operations, streetcar / trolley, or industrial railroads (terminal switching, steel mill, logging, et al.) In 1956, they became better known as clearance plates; but for now we will only concern ourselves with the era in which the Erie L1's operated: 1907-1930. The alleged clearance interference between the cabs of the Erie L1's as allegedly stated by the "defendant"; I refer you to the diagram at right "Railway Line Clearances" as published. Please note, the overall width allowable by a piece of equipment is 15 feet; or 7 feet 6 inches to either side of the centerline of the track. These clearances are for main lines and passing sidings; not secondary lines, industrial or plant sidings, loading platforms at warehouses, coach yards, etc. If one now refers to the diagram below right, which are the dimensions of the Erie L1 as contained within the original American Locomotive Co. plans; we will see that the maximum width, which is the cab of the locomotive; is 151". 151" = 12.58 feet, or slightly over 12½ feet, and is precisely 12 feet 7 inches. Therefore, the maximum width of the Erie L1 is LESS THAN the maximum allowable loading gauge / clearances prescribed for that era of operation. These clearances have existed since 1886 and are the dimensions shown are minimums for standard mainline operation. These dimensions have steadily grown larger over the decades and were contained (in part or in whole) in many public references for new railway construction as well as in standard railroad references (Railway Engineering, Master Car Builders Association, Official Guide of the Railways, et al.) These references were usually published annually and could be found in the offices of railroad physical & mechanical engineers; maintenance of way department heads and track superintendents; among many others. The Official Guide further noted individual size and weight restrictions for each class of freight car for large and small railroad lines and industries. This standard reference could be found in just about every freight depot, yardmasters offices; and on freight traffic directors shelves; Do you think for even one minute, the American Locomotive Company in 1907 constructed a locomotive so incredibly huge, without first checking track clearances, tunnel clearances, and other restrictions on the Erie Railroad where it was going to be used? 8.4: The L1's: Shipping Them Over Two Railroads In addition, the Erie L1's didn't just magically materialize in Susquehanna upon being constructed. They obviously had to be moved from where they were built, to where they were going to operate. The Erie L1's were built by American Locomotive which was located Schenectady, NY. To get to Susquehanna, PA; the most direct route by railroad would have been: