My ride to Los Angeles.

Northbound Coast Starlight awaiting departure at 10:10

AM, with arrival in Seattle tomorrow night at 8:12 PM.

Boarding on the Coast Starlight on Track 10.

An excellent reason to ride the Starlight is the first

class lounge parlour car.

Number 14 pulled

out on time at 10:10AM and now it was time to walk

through the station and on to Chinatown.

Alright you ivory ticklers, entertain us.

Ticketing room.

Waiting room looking toward the tracks and

platforms. Little gift shop has been removed.

Union Station front.

Walking to N.

Alameda St and then up to Cesar Chavez Avenue and

then west on Cesar Chavez to North Spring St to my

first stop. The King Hing Theatre.

King Hing Theater, 647 N. Spring Street.

The

375-seat King Hing Theatre, originally named

the Sing Lee Theatre, opened in 1962. It was

designed by Gilbert L. Leong, a native

Angeleno and the first Chinese American to

graduate from the USC School of Architecture.

The theater was a popular destination for the

community, helping to make Spring Street a

thriving local hub between the 1950's and the

1970's. The King Hing Theatre showed Chinese

language films and hosted live performances,

including Chinese operas. It stopped operating

in 2001.

This

was the first stop for tour goers. Inside a

program was presented to give some history

and background of Old and New Chinatown.

Among the speakers were Sara Lann, Director

of Education, LAC, plus a docent from the

Chinese American Museum, and then

former council member Mike Woo. Some notes

from the program.

Full house in attendance for start of tour

presentation.

Wedged between Elysian Park to the north,

and Lincoln Heights and Echo Park to the

east and west, Los Angeles' Chinatown

spans a little less than a mile. Along

with iconic symbols of classical East

Asia-tiled roofs, red lanterns, and

wishing wells-exists the history of one of

Los Angeles' oldest neighborhoods.

The streets and parcels

that formed the community's center were

plotted in L.A.'s first official city survey

in 1849, one year before California became a

state. No other area of the city, except

downtown, was mapped out before this

location. Photographs taken in the mid-to

late nineteenth century show modest houses

surrounded by wooden fences, separating wide

lots from their neighbors and the dusty

road.

What is now know as

Chinatown wasn't the first in Los Angeles.

The first permanent settlement of Chinese

immigrants centered around El Pueblo de Los

Angeles, the city's birthplace. Most of

these residents were miners and laborers,

men from the Guangdong province who traveled

to California in search of better

opportunities. Many found employment working

on the railroads.

From the outset,

Chinese Americans faced discrimination on a

systemic level, evidenced by the jobs they

were allowed to have, the places they were

allowed to live, and the spats of

violence their community endured from

others. Still, Chinese immigrants continued

to settle and prosper in Los Angeles. This

first Chinatown became a thriving hub of

Chinese residences and businesses complete

with schools, temples, theaters, and

restaurants. But the denial by city

officials of public services to the Chinese,

such as sewer systems, paved roads, and

electricity, created a health risk. A

proposal to raze the neighborhood in favor

of a new railway terminal to be built on

this site was issued in 1913; over the next

decade, anti-Chinese sentiment and

excitement for Union Station led to the

neighborhood's ultimate destruction. At the

time of what is now known as Historic

Chinatown's condemnation in the 1930s, there

were close to 3,000 Chinese Americans living

in Los Angeles, most of whom faced

displacement.

Today's Chinatown

was born as a destination as well as a

community. Its founders envisioned a place

that would serve and protect local Chinese

American residents, as well as draw visitors

to partake of its unique offerings. For many

tourists, Chinatown's cuisine was the

biggest draw. When Chinese American

migration to the San Gabriel Valley began in

1970s, many of the massive dim sum palace

restaurants moved with them. The ones that

stayed struggled to keep afloat through

decades of economic decline.

In recent years,

Chinatown had attracted new business and

development that has brought new visitors to

the area. An influx of art galleries, along

with young, trendy eateries, offer new

options alongside Chinatown's established

shopping and dining institutions.

And speaking of trendy

eateries, it was lunch time. So I headed to

Ord Street and then down to Philippe The

Original. I left the presentation a few

minutes early to try to beat the crowd to the

lunch counter. Yes it was crowded, but the

wait was only a short ten minutes before I

could order my beef stew, coleslaw and

lemonade. I sat in the little room with the

model railroad display. Another reason to eat

at Philippe's.

After my nice repast it was

time to start touring. Walking out the door

and turning right, I went up Ord St. to my

next stop at Ord and Broadway.

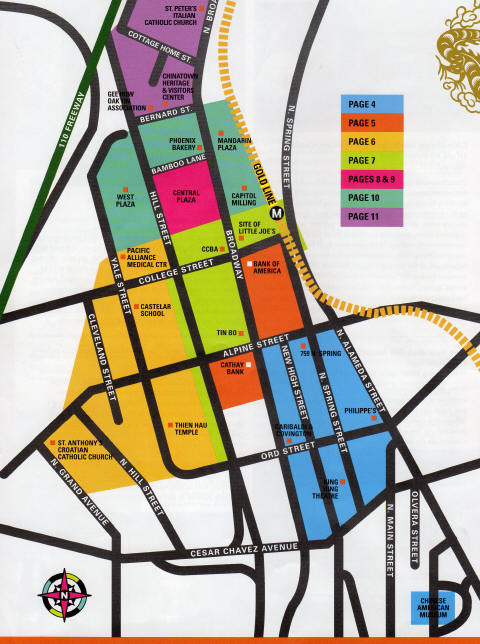

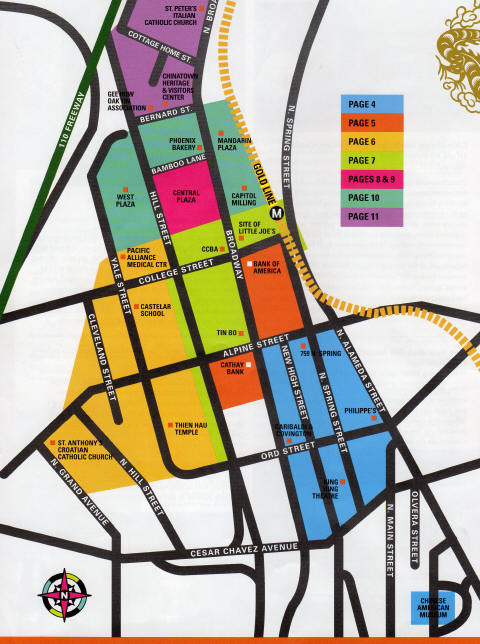

Broadway and Ord Street.

.

map courtesy of Los Angeles Conservancy.

Garibaldi Building, Northeast corner of Broadway and

Ord Street.

1906, R.B. Young

Covington Building, Southwest corner of Broadway and

Ord Street.

1913, Hudson & Munsell

The Garibaldi

and Covington buildings, located in the heart of

what was once Little Italy, are among the last

intact commercial buildings associated with

Italian ownership in the neighborhood.

The Garibaldi

Building housed S. Peluffo & Sons grocery for many

years. Italian immigrant Stephen Peluffo was one of

the city first wholesale grocers and also owned a

winery. The Covington Building likewise catered to

businesses owned by Italian immigrants. Both buildings

had apartments on their second floors.

Continuing on Ord St. to Hill St.

At Hill turned right and headed north to Alpine Street

then left Alpine to Yale Street. Going up Ord Street

would mean a steep climb up the hill. The Alpine

Street was a gentle climb.

After turning left, I could see my

next stop. The Thien Hau Temple, 756 Yale Street.

2005.

Thien Hau Temple was built by the

Camau Association of America, a benevolent association

that serves immigrants from Vietnam along with other

East Asian populations. A Taoist temple, Thien Hau

Temple is dedicated to Mazu, the goddess of the sea

and patron saint to sailors and fishermen. Many

residents of Chinatown came from communities in

southeastern coastal areas of China, which, along with

Vietnam, have strong ties to the ocean. Other shrines

in the Thien Hau Temple are dedicated to the warrior

Guan Yu and earth god Fu De.

Chinatown saw waves of immigrants

from Taiwan and Hong King after the repeal of the

Alien Quota Act in 1965. After the Vietnam War, a

flood of Indochinese refugees including Vietnamese of

Chinese origin as well as ethnic Vietnamese,

Cambodian, Laotian, and Thai Immigrants arrived,

growing Chinatown's population and diversity. Today,

the culture of Chinatown is a more inclusively Asian

one, as seen in institutions such as Thien Hau Temple,

where people from multiple backgrounds come to pray.

Thien Hau Temple, 756 Yale Street, 2005

Leaving the

temple I walked back to Alpine and then back to

Hill Street. Going north on Hill Street, I arrived

at the next stop.

Pacific Alliance Medical Center

531 W. College Street

Originally the French Hospital.

Constructed

by the French Society, the French Hospital was

founded in 1869. It offered healthcare and

medical services to French American citizens

and newly arrived French immigrants, as well

as to the greater community regardless of

nationality, race, religion, or gender. Now

known as the Pacific Alliance Medical Center

(PAMC), it is the second-oldest hospital in

Los Angeles. Still on its original site, PAMC

has been remodeled several times, most

recently in the 1960s. A visible sign of the

hospital's history is the statue of Joan of

Arc at the corner of Hill and College Streets,

a reminder of the French community's presence

in the neighborhood's early days.

Continuing

north on Hill Street is my next stop: West Plaza.

West Plaza, Hill Street between Bernard and

College Street.

Located across Hill Street from the Central

Plaza, the West Plaza was developed after

World War II and opened in 1948. The design of

the complex features Chinese elements, such as

green tile roofs with upturned eaves, and a

wishing well. The overall aesthetic of the

West Plaza is more modern in style and more

subdued in decoration than Central Plaza. It

was intended to cater to the neighborhood

rather than to tourists. Across Hill Street is

the West Gate.

West Gate.

Two of

the most iconic structures in Chinatown

are the welcome gates leading to the

Central Plaza on either end of Gin Ling

Way. The West Gate (on Hill Street) was

erected in 1938 as part of the initial

development of the Central Plaza. Its

traditional design included 150-year old

camphor wood from China. The Chinese

characters translate to "Cooperate to

Achieve."

Continuing north on

Hill Street to Bernard Street and arrived

at my appointed duty station. I had

arrived a little early and the site

captain Cindy said it was OK to take off

and come back in 30-40 minutes. I decided

to walk down Broadway. I was going to do

it later on the way home but now I could

get inside the Cathay Bank while it was

still open. I walked down Broadway to

Alpine Street and would return taking time

to return.

Cathay Bank

777 N. Broadway

1966, Eugene Kinn

Choy & Associates

Cathay Bank was born of necessity:

in 1962, Chinese Americans in Los

Angeles faced discrimination by

financial institutions and

businesses that often denied them

loans and other banking services.

Founded by prominent businessmen in

the Chinatown community, Cathay Bank

was the first Chinese American bank

in California and the first to

specifically address the needs of

the rowing Chinese American

population. Its commitment to

equality is reflected in its motto:

An Open Door to All. Cathay Bank has

since opened branches throughout the

nation and world.

Cathay Bank was

designed by Eugene Kinn Choy. A

graduate of USC's School of

Architecture. Choy became the second

Chinese American to join the

American Institute of Architects.

Other buildings of Choy's in

Chinatown include Broadway's Chinese

Consolidated Benevolent Association

(CCBA) and the Jin Hing Jewelry

Store on Bamboo Lane. Like the CCBA,

Cathay Bank is a hallmark of Modern

design combined with traditional

Chinese architectural elements.

Choy's use of the International

Style of Modern architecture is

augmented by the four Chinese

characters running vertically down

the front facade of the building,

while the roof evokes the classical

wood roofing of Chinese structures.

Choy specifically incorporated these

details to honor the request of

Cathay's founders, who wanted the

banks design to reflect their

cultural heritage. The convergence

of traditional Chinese custom and

modern innovation seen in Chouy's

work is an apt reflection of the

Chinatown community.

As no photography

was allowed, I have no pics of

inside. One interesting item were

the counters where you stand to fill

out your paper work before heading

to the teller window's,

embedded in the counter's top was

an abacus. There were several

in the lobby. Were they the earliest

binary computers? The bank hostess

were handing out nice tote bags. I

asked if there were any free samples

included. But Alas, No photography,

No free samples. But of course I

left in a huff and walked up

Broadway.

My next stop was

a quick walk through and look see.

Tin Bo Inc,

841 N. Broadway.

One of

many excellent herb stores in

Chinatown, Tin Bo carries a wide

selection of teas and herbs, including

what are considered the "big three"

health supplements in Chinese

medicine: ginseng, reishi mushrooms,

and deer antler. They are believed to

improve energy levels, body function,

and longevity. Chinese medicine and

apothecaries such as Tin BO were a

part of Chinatown from its earliest

days: Chinese companies imported

specialty herbs for their workers, and

Chinese groceries often stocked

medical ingredients alongside food

items.

I walked to the

next block and the location of the

Chinese Consolidated Benevolent

Association.

Chinese Consolidated Benevolent

Association

925 N. Broadway

1951, Eugene Kinn Choy &

Associates

Formally organized in 1890, the

Chinese Consolidated Benevolent

Association (CCBA), was formed to

promote and protect Chinese

Americans on both social and

political fronts. It continues to

pursue this mission today,

representing nearly thirty family

and district associations.

The CCBA

relocated to its current home,

designed by Eugene Kinn Choy, in

1951. This unique civic structure

exemplifies the East Eclectic

style of many buildings

commissioned by New Chinatown

businesses and institutions.

The next stop

was a sweet one.

Phoenix Bakery

969 N. Broadway

1977, Gilbert L. Leong

The Phoenix Bakery opened on

New Chinatown's Central Plaza

in 1938. It originally

supplied the community with

Chinese pastries that were

difficult to come by in the

U.S. The logo of a boy

hiding a pastry box behind his

back was created in the 1940's

by Tyrus Wong, who also

painted the Central Plaza's

dragon mural: the logo was

modeled after one of the

children in the extended

family of bakery owner Fung

Chow Chan. With more business

than it could now manage, the

bakery opened its current

location in 1977. Still owned

and operated by

third-generation Chans, the

Phoenix Bakery continues to

produce hundreds of its

trademark whipped cream and

fresh strawberry cakes every

week.

Across Broadway at 970

N. Broadway is the Mandarin Plaza. As I

was running short of time I didn't visit

this site. It was now time to return to my

duty site and check in at the Gee How Oak

Tin Association, 421 Bernard Street. Also

on Bernard Street are two homes next to

the Association.

415 Bernard Street.

411 Bernard Street.

Chinatown Heritage and Visitors Center.

These two working-class homes harken

back to Los Angeles' early

development. The one-story frame

cottages are rare surviving examples

of the type of residences that once

made up the neighborhood.

Distinctive features such as roofs

with shallow eaves, decorated

gables, simple porches, and wood

clapboard siding exemplify the Queen

Anne Style of the late nineteenth

century. The homes were built by

Alsatian immigrant Philip Fritz, a

carpenter for the Bridges and

Buildings Department of the Southern

Pacific Railroad.

There were

three houses constructed on adjacent

lots over a seven year period;

411 Bernard (which now houses the

Chinatown Heritage and Visitors

Center) was the first built, in

1886. A second house was built in

1888, but was moved to another

location in the 1930s due to street

widening, and has since been

demolished. 415 was built in 1892.

The three homes were often rented to

railroad workers when not being used

by the family. Philip Fritz' three

children and their families lived in

the homes at various times. Philip

Fritz' granddaughter, Louise, was

living in this house, (411) until

her death at 101 in 1992.

Currently

owned by the Chinese Historical

Society of Southern California, the

buildings house a research

collection, bookstore, artifacts,

and displays related to local and

national Chinese and Asian American

history.

Now it was time to

check in with the site captain at the Gee

How Oak Tin Association, 421 Bernard

Street where I was assigned to welcome

tour goers to the second floor main common

room area.

In the nineteenth

century, Chinese men in Los Angele

created a number of family associations

to provide support, protection, and

social ties within the community. With

discriminatory immigration laws severely

limiting Chinese women's ability to

immigrate, the associations offered

meals, healthcare, and camaraderie for

immigrant men working in a strange new

country.

Formed around

surnames identifying common lineage,

family associations offered new

immigrants assistance with job

placement, housing, English lessons,

financial counsel, and funeral services.

They also offered the opportunity to

connect with fellow countrymen through

activities ranging from mahjong games to

charity work.

The Gee How Oak

Tin Association is one of approximately

forty family associations in L.A.'s

Chinatown that continue to serve the

local population as well as new arrivals

from China and Southeast Asia. Inside

the Association building's common room

hangs a picture of the ancestor believed

to be the common link to the various

families that make up Gee How Oak Tin:

the Chans, Chens, Chins, Trans, Woos and

Yuens. Photos documenting multiple

generations of these families ring the

walls. Gee How Oak Tin (meaning "Most

Filial") is an international

organization, and, according to its

members. one of the largest in the

United States. The L.A. Chinatown

chapter comprises 400 to 500

members-including women, who were

officially allowed to join more than a

decade ago.

This building

was built in 1949 for and by the

Association and was deigned by Eugene

Kinn Choy, an important Chinese American

Architect.

Emperor Shun, circa 2318 B.C., who was a descendant

of Huang-Ti, the "Yellow Emperor" of Ancient China

(3000 B.C.).

Offering for association's members common ancestor.

A few mahjong game pieces.

I had a great

time welcoming tour goers plus getting help from

association's members that were on hand to answer

questions and talk more about the Association and

the decorations. I met many people including a

fellow Fullerton meet up train rider and photo

travel writer Carl Morrison. He was taking the

tour with several friends and having an enjoyable

time learning about Chinatown.

Soon it was 4:30 PM and time to

close up. Reports were that the tour was a big

success. Over 800 people were learning about and

enjoying Chinatown. They were looking, buying, and

eating everywhere. A happy time was had by all.

Leaving 421 Bernard Street, I

walked down Broadway heading for the Gold Line

Chinatown station. Walking past the Central Plaza,

I was spotted by Bruce S., who asked me if I had

seen the inside of the Y. C. Hong Office Building.

I hadn't but wanted to, Bruce said I could join

one of the last tours of the building. As this was

a NO photography allowed building I have no inside

photos.

Y. C. Hong Office Building

445 N. Gin Ling Way

1939, Webster & Wilson

Carved

brackets and rafter tails, Chinese-influenced

ornamentation, and a neon silhouette makes

this building a prime example of the East Asia

Eclectic style exemplified in New Chinatown's

Central Plaza. Yet the upstairs office of

lawyer You Chung Hong make it truly special.

The son of a Chinese

immigrant who worked on the railroads. Hong

was the first Chinese American to pass the

California Bar exam in 1923 and before he

graduated from USC's law school. He

specialized in immigration law and devoted his

career to Chinese American civil rights, which

led him to testify before the U.S. Senate and

to appear before the U.S. Supreme Court. Hong

worked on thousands of immigration cases,

always championing the Chinese American

population he served. An active member of the

community outside of his professional career,

Hong contributed greatly to New Chinatown. He

served as one of its founders and commissioned

multiple buildings on Gin Ling Way, including

his office building.

The upstairs tour included

the reception area and Mr Hong's corner office

which is almost the way it looked when he used

it. In one of the several rooms included in

the suite was a display by his granddaughter,

Celeste Hong. She remembers her grandfather

and had several pictures of her and her

grandfather. He died when she was around nine

years old. It certainly added to the tour to

have person connected and related to the owner

and builder. Celeste is also a volunteer at

the LAC and I have been on several committees

with her.

The buildings around the

Central Plaza were designed with shops on the

first level and living space above. Brightly

painted facades and clay-tiled roofs gave a

welcoming charm to the neighborhood.

Today, Central Plaza serves

much the same purpose as it did then: shops

and businesses are still owned by many of the

original founding families, and the neon

lights added shortly after the buildings'

completion create a festival feeling at night.

Also at the Plaza are statues of the first

president of the Republic of China, Dr.Sun

Yat-sen, and action star Bruce Lee.

Moon over East Gate.

The elaborate East Gate (facing Broadway)

was dedicated on the one-year anniversary of

the Plaza.

Commissioned by Y.C. Hong is honor of his

mother, it is known as the Gate of Maternal

Virtues.

Blimp over Dodger Stadium and the Y.C. Hong

Office Building.

Bruce.

Where I stopped to eat before heading home.

Leaving

Central Plaza, I walked down Broadway to

College Street. At Broadway and College is

located the Bank of America.

Bank of America

850 N. Broadway

1972, Gilbert Leong and Richard Layne Tom

The

first major national bank to move to

Chinatown, Bank of America decided to open

a branch there only after watching the

success of Chinese-American-owned banks

such as Cathay and East West Bank.

Architect Gilbert L. Leong incorporated

classical Chinese architecture into the

Modern structure through features such as

an imported jade-green tile roof. Leong

built many iconic structures in his

childhood neighborhood, including East

West Bank (where he served as a founding

director), the Kong Chow Family

Association and Temple (931 N. Broadway),

and the the Chinese United Methodist

Church (825 N. Hill Street).

Chinese Methodist Church.

825 N. Hill Street.

Gilbert L. Leong

I

continued downhill on College Street

to the bottom and to the elevator to

whisk me up to the Metro Gold Line

Station platform. On the other

side of the street are the stairs to

the elevated platform. Arriving at

the platform stop, I only had time

for one photo before a rail car was

blocking my view. I could have

stayed and waited for a later train

as I had some time before the

Surfliner left Union Station. Be

sure to tap your metro card before

riding up in the elevator.

The painted buildings to the left

are part of the Blossom Plaza

project. When completed there will

be a level walkway from the Metro

Station on to Broadway, thereby

eliminating the steep climb up

College Street to Broadway. It

occupies the site of the former

Little Joe's Restaurant, 900 N.

Broadway, 1888, B.J. Reeves.

In 1928, Little

Joe's Italian American Restaurant

was established on the corner of

Broadway and College Street. It

occupied an 1888 building that had

once been a grocery. The business

remained in the Nuccio family,

second-generation owners of the

original grocery until its closure

in 1998. Several years later, the

building was demolished. Now, the

site is home to the Blossom Plaza

project, a $100 million

residential-retail complex that

includes townhouse-style

apartments as well as affordable

housing units.The appealing

five-story buildings were inspired

by Chinese architecture and herald

a revived interest in the

neighborhood.

Before I knew

the history of Chinatown, I always

wondered why there was an Italian

restaurant in the middle of

Chinatown. Now I know.

Capitol Milling

Company

1231 N. Spring Street

1855

1884 addition, Kysor & Morgan

1889 addition, Kysor, Morgan &

Walls

Despite the clearly legible "Est

1883" painted on the side of

Capitol Milling Company's

building, parts of the brick

structure have been standing for

much longer. The brick mill

produced flour from 1855 until

1998, when the company was sold

and the building acquired by San

Antonio Winery. Capitol Milling

harkens back to the agricultural

industry that once flourished in

the area. Los Angeles was still

a rough Mexican outpost of

approximately 800 people when

water from the ditch that

provided early settlers with

water, the Zanja Madre, powered

Capitol Milling's water wheel.

The company (known first as

Eagle Mill, the as Deming Mill)

would eventually be named

Capitol Milling by owners Jacob

Lowe and Herman Levi, German

American Jews who purchased the

mill in 1883. Capitol Milling

stayed in the Levi family until

its closure in 1998, making it

the longest-running family-owned

business in Los Angeles.

It was a very

short ride from Chinatown and Los

Angeles Union Station. The

original Metro plans had no stop

in Chinatown. They neither planed

nor wanted a stop so close to

LAUS. The locals were able

to show Metro the error in their

thinking. Now the Metro Gold Line

Chinatown stop is one of three

stations designated as "landmark"

stops by Metro (in addition to

Southwest Museum and Memorial

Park).

Upon arriving

at LAUS with about three quarters

of a hour till Pacific Surfliner

train 1790 departed, I waited in

the waiting room. A wonderful room

and a great place to people watch.

I was keeping track of the

arrivals and departures boards.

Train 1790 left San Luis Obispo,

CA at 2:00PM with arrival in Los

Angeles at 7:20 PM. The southbound

trains going through Los Angeles

to San Diego, CA tend to be

heavily occupied, and Sunday

afternoons and nights are the

busiest. So I wanted to be on the

platform when the train arrived

and ready to grab a seat. The

census was about 70% filled. The

horn sounded and we were pulling

away from the platform as the

clock struck departure time. After

36 miles and one hour I was

walking in the Santa Ana parking

structure to my auto. A quick trip

on the freeway and I was home.

Web page:

Click

here for the Los Angeles

Conservancy

Click

BACK

button on your browser to

return to this page.

And a

special thanks to the Los Angeles

Conservancy.

Data used

in this report was obtained from

their booklet: Exploring

Chinatown: Past and Present Tour,

April 17, 2016.

The author retains all rights.

No reproductions are allowed

without the author's consent.

Comments are appreciated

at......yr.mmxx@gmail.com

Thanks for reading.