|

McCloud River Subsidiaries and Affiliates Pit River Railroad |

|

|

|

The Pit River is the next major river system south of the McCloud River. The original human inhabitants referred to the river as It'Ajuma, which roughly translates to Big River. The river was their lifeblood in more ways than one, as it carried vast seasonal salmon migrations providing roughly half their diet. Europeans applied their name to the river due to the large pits the natives dug along the banks to trap game. The Pit originates in two forks in Modoc County, far to the east of the McCloud region. The South Fork starts in Jess Valley and flows generally north, while the North Fork starts near the small community of Davis Creek, CA, and flows southwest. The two forks join together in the city of Alturas, CA. The river's main stem then flows southwest on a gentle gradient for 207 miles to a confluence with the Sacramento River north of Redding. The river varies from meandering streams in broad valleys to raging torrents at the bottom of deep rocky canyons. The watershed drained by the Pit River and its subsidiary streams measures 4,900 square miles in size. The Pit River became a natural corridor for early commerce through the region, and numerous railroad surveyors ran lines for proposed routes along the river. One of them, J.R. Scupham, recognized the Pit's hydroelectric generating potential while surveying a potential route for the Central Pacific Railroad in 1875. Scupham produced a report of his findings in 1883, but nothing could be immediately done to act on his plans. Even if a powerhouse could be built, the market conditions justifying constructing the infrastructure needed to transport electricity produced on the Pit to the major markets did not yet exist. The first movement towards establishing hydroelectric operations on the Pit came around 1909. Two companies, the Mt. Shasta Power Company and the Northern California Power Company, both drew up plans and commenced a little bit of construction on a pair of power houses and related facilities to be built in the area of Big Bend. Both projects encountered financial problems and failed. California utility giant Pacific Gas & Electric Company had been looking at the Pit River as a potential site for future hydroelectric projects, and the spike in electricity demand following the conclusion of World War I finally made such developments economically feasible. PG&E first needed to secure the water rights, and to that end the company purchased the Mt. Shasta Power Company in 1917 and the Northern California Power Company in 1919. PG&E's initial plans called for a total of five hydroelectric plants to be built along the river by a new subsidiary, the Mount Shasta Power Corporation. All efforts to this point had centered around the proposed plants at Big Bend; however, PG&E decided to start with the furthest upstream plant and work downstream from there. PG&E projected construction to last through 1935 and estimated its final total investment in the Pit River projects at $100,000,000, a staggering sum in 1921 dollars.

Origins of the Railroad

As PG&E started developing its Pit River plans, the utility entered into an agreement with The Red River Lumber Company to build a pair of small powerhouses on Hat Creek, a tributary to the Pit River southwest of Fall River Mills. Red River owned the power plants, and PG&E operated them under contract. The two plants entered operation in August and September of 1921. Transportation proved to be one of the biggest hurdles the utility faced in the Hat Creek project. All supplies and construction materials had to be teamed in over the rough and often impassible wagon roads, which turned out to be a long, slow, and costly process. The Hat Creek plants were tiny when compared to the contemplated Pit River projects, and PG&E concluded they needed a railroad to transport the Pit project construction materials. The nearest railhead to the proposed projects lay at the McCloud River Railroad mainline at Bartle, and the utility approached the railroad with a proposal to construct a line from there to the Pit River. McCloud agreed, and the two parties started sorting out logistics. The Red River Lumber Company owned most of the land the new railroad had to cross, and they granted a right-of-way to the utility but stipulated the railroad could not be a common carrier. Roadbeds of McCloud River Lumber Company's Spur 51 system extending southeast from Bartle could be used as part of the new line, and the lumber company leased 4.2 miles of grade to the railroad and the power company for this purpose. California suffered through a prolonged drought through the late 1910s, drying up several streams feeding existing powerhouses in the Sierras. PG&E needed new electricity supplies in a big hurry and did not have the luxury to wait for good weather. Two survey parties went to work in the winter of 1920-1921, one supplied by PG&E under the direction of E. H. Hatch and the other supplied by the McCloud River Railroad under the direction of Charles Daveney. The two crews worked through the winter, often in drifts up to fifteen feet deep. The route they selected ran from Bartle southeast over Dead Horse Summit. The line then looped in and out of drainages on the descent to Cayton Valley and included a balloon track above the valley, likely used to turn snowplow trains clearing the line over the pass. South of Cayton Valley the railroad dropped down to the Pit River, which it followed on the north bank all the way to the Pit 1 powerhouse site. Total length of the line stood at thirty-three miles. The railroad would officially be known as the Mount Shasta Power Corporation Railroad. However, the line became better known as the PG&E Railroad or, more commonly, the Pit River Railroad. On 2 May 1921, G.B. Milford, the superintendent of PG&E's Shasta Division, publically announced the utility would start constructing the railroad shortly, and that the subsequent power development would make Shasta County “one of the greatest water power development sites in the world”. The McCloud River Railroad built the railroad at cost plus ten percent. The railroad initially built a 102-foot long connection with the utility's new line near Bartle at a total cost of $430.19, commencing work in April 1921 and completing the work in July. Grading the new railroad and building six large trestles started on 22 May, and rail laying started in July. The job employed 400 men during the grading portion and 250 during the track building. The construction crews finished the line on Saturday, 17 September 1921, and PG&E officially celebrated the event with a gold spike driving ceremony the following day. Total cost of the initial railroad construction amounted to approximately $500,000. Newspaper records suggest the McCloud River Railroad purchased a large quantity of rail from the then-abandoning Ocean Shore Railroad; it is possible the rails were re-used in the Pit River Railroad. PG&E contracted the construction, operation, and maintenance of the line out to the McCloud River Railroad and leased three McCloud locomotives as initial power for the road. Rental rates the utility paid to the railroad for railroad equipment have been reported as $3 per hour for locomotives, $1.50 per hour for snow removal equipment, $1 per day for boxcars, $0.50 per day for flatcars, $0.25 per day for outfit cars. The completed railroad included eleven automobile road grade crossings, three on the Cayton Valley road, one on the Fall River Mills road, and seven on the county road following the north side of the Pit River. PG&E reached initial agreements with Shasta County allowing the crossings; however, the utility concluded it needed the state's blessings as well, and on 19 December 1921 Mt. Shasta Power Corporation and PG&E jointly submitted an application to the California Railroad Commission for permission to build the crossings. The Commission approved the application on 30 January 1922, requiring the utility to bear all costs of installing marking, and maintaining the crossings.

Pit 1

PG&E designated the first of the plants to be built as Pit 1. The Fall River runs south through its namesake valley (named Bo'ma-Rhee by the Ahjumawi) to a confluence with the Pit in the small farming community of Fall River Mills. Immediately west of the confluence the Pit drops into a deep rocky gorge, through which it winds for a few miles until emerging into a narrow valley. The Ahjumawi beliefs held that Kwaw (Silver-Grey Fox, one of the creators of the world) forgot to make a channel for the It'Ajuma to flow, and to rectify the situation he summoned a huge fish that got its power from the top of Ako-Yet (Mt. Shasta). The fish repeatedly rammed its head against the solid lava rock mountain until it formed the present gorge, providing a place for the waters to flow and allowing the salmon to come up river. Deep in the bottom of the gorge is a waterfall, named Inalah-Haliva by the Ahjumawi (variably, Where the salmon turn back or Where they struggle to get up under the water and over the falls, but can't). The waterfall posed an insurmountable obstacle to any further upstream fish movement. In later years, Europeans would expend vast sums of money and effort trying to build fish ladders and other passage structures around the falls to open up the rest of the river to salmon, but none of the projects succeeded. The Pit 1 project consisted of a 500-foot long earthen dam on the Fall River immediately upstream from Fall River Mills, impounding a small lake. A 1,000-foot long intake canal would be constructed at the upper end of the lake, diverting the water into a two mile long aqueduct passing underneath Saddle Mountain along the north side of the gorge to the power house. The power house would be located right next to the mouth of the rocky canyon, and the water transported through the aqueduct would come out of the tunnel 454 feet above the stream. The water would be dropped through pipes, run through the turbines, and then released into the Pit River. Construction of the Pit 1 project started even before the completion of the railroad line. The project stood out as one of the biggest industrial undertakings in the state to that time, and almost certainly one of the most remote. In addition to the facilities on the river, PG&E also had to build a 202-mile long transmission line from the powerhouse to a completely new substation built just northeast of Vacaville, California. Work on all aspects of the project accelerated with the arrival of the railroad and extended through the winter. PG&E's employee magazine carried a story in its April 1922 edition written by H.S. Furlong of the Publicity Department about a trip he took with Engineer Peterson and Assistant Engineer Keeling to the Pit 1 project sometime during the same winter. The trio arrived by train into McCloud, only to find the McCloud River Railroad's plow train had broken down at Slagger Creek. The trio spent four mind numbing days in the Hotel McCloud waiting for the railroad to rescue the plow train before they could head for Pit 1. The three men found themselves crammed into a caboose with forty other men on a plow train consisting of the plow, four locomotives, a flanger, and the caboose. The men rode the train as far as Cayton Valley, where the train turned back for McCloud and the men continued on to Pit 1 in a speeder. In late February 1922, a local newspaper carried a story about a snowplow train powered by four locomotives that struggled for five days to open the line from Bartle to Pit 1 through snow drifts up to seven feet deep; this could refer to another event on the railroad that winter, but could also be a misreporting of the five days involved in getting the PG&E officials to Pit 1 due to the problems elsewhere on the McCloud River Railroad. A partial list of the materials used in the Pit 1 construction shows the size and scope of the project. The list includes 12,298 tons of steel (power house, penstocks, transmission towers, substation); 22,150 barrels of cement; 1,052,088 board feet of lumber, not counting 75,000 railroad ties used in the building of the Pit River Railroad and 1,169 sixty-foot tall poles; 58,461 cubic yards of concrete; 517 tons aluminum cable; 4,333 tons of 48-strand copper cable stretching 1,041 wire miles (one news report remarked that the individual strands in the cable, if unstrung and laid end to end, would stretch 50,000 miles); 3,171,000 pounds of insulators; 1,663 steel towers; 10,111 feet of tunnel; 401,796 cubic feet of excavation; 31 miles of railroad construction; 105,330 pounds of blasting powder; 138,800 feet of fuse and 33,000 blasting caps; and four million megawatt hours of electricity generated in auxiliary plants for use in the construction efforts. The powerhouse contained two generating units that were the largest anywhere in the United States and the second largest to be found anywhere in the world. The two units produced a combined output of 93,800 horsepower. The power transmission line had a maximum capacity of 220,000 volts, making it the highest capacity transmission line built to that date. At the other end of the transmission line PG&E built the Vaca-Dixon substation, one of the largest such facilities constructed to that time. Equipment installed there included two 20,000 kva synchronous condensers to regulated the voltage received from the Pit River powerhouses. Seven 16,667 kva transformers reduced the 220,000 volt input down to 110,000 volts for re-transmission to other distributing substations. Most of the electricity produced by the Pit River projects would be used in the greater San Francisco bay area. Construction on the substation started in August 1921 and finished on 15 September 1922. Total cost of the facility amounted to $1,250,000. The labor needs of the project placed a lot of men in an area without the infrastructure to meet their daily living needs. PG&E established twenty construction camps and boarding houses to accommodate their work force, which averaged 857 men employed each day for twenty-six consecutive months. Total man days worked during the Pit 1 construction amounted to 668,506. PG&E provided approximately 991,731 meals during the construction at a total cost to the company of about $255,725. Preparing these meals consumed 206 tons meat; 38,900 dozen eggs; 34½ tons hams and bacon; 121 tons flour; 159 tons potatoes; 15 tons onion; 12 tons beans; 4 tons rice; 4 tons pastes; 67½ tons sugar; 23,408 gallons canned fruit; 19,500 gallons canned vegetables; 20 tons butter; 84,200 cans milk; 8¾ tons lard; and 12½ tons dried fruit. Construction crews completed the power house structure of 30 July 1922, and on 28 August other crews finished lining the tunnel. Continued work finished the project by late September, and on 30 September 1922 the utility officially placed the powerhouse in service. Special trains carried five hundred people to the Pit 1 powerhouse, and an additional 5,000 people packed into the Vaca-Dixon substation. Various official and public dignitaries gave speeches at the two sites. PG&E president Charles E. Virden and A.S. Dudley, manager of the Sacramento Chamber of Commerce, spoke at the substation, while Dudley V. Saeltzer (president of the Northern California Counties Association) and R. C. Evans (manager of the Redding Chamber of Commerce) spoke at Pit 1. After the dignitaries finished speaking a PG&E official flipped a switch at the power plant energizing the transmission line. A special light announced the arrival of the first electricity from Pit 1 to the Vaca-Dixon substation, and current from this initial flow powered a motor raising an American flag over the facility. The event marked a significant forward step in the further development of central California, and the press of the time widely reported on the event and its importance. Total cost of the project amounted to $18 million dollars by the time the Pit 1 powerhouse supplied its first electricity to the electrical grid.

Pit 2

Once Pit 1 entered operation, PG&E turned its attention to the next projects downstream. Initial plans for Pit 2 included a diversion dam right at or above the Pit 1 powerhouse, 2½ miles of open canal, a spillway, a header box, penstocks, a powerhouse, and a tail race. Total capacity of this powerhouse was to be 23,500 horsepower. However, PG&E decided not to build this part of the project, possibly because the engineers planning the project misread key topographical information.

Pit 3

Pit 3 was the next completed project downstream. Initial plans for this project called for a one hundred foot tall diversion dam impounding a reservoir approximately 32,500 acre feet in size. Water from the reservoir would be fed through a four mile long aqueduct to the powerhouse. The water would emerge from the aqueduct at a point 313 feet above the stream surface. This powerhouse had a planned 90,500 horsepower capacity. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) licensed this project on 23 October 1923. Work on the Pit 3 dam started in early 1923. To support this construction effort, the utility built a five mile long branch of the Pit River Railroad, extending from Cayton Valley to the dam site. This line included several substantial timber trestles carrying the tracks across the rough and broken terrain. On 15 September 1923, the Redding newspapers reported the passage of a special train carrying 150 prominent citizens from Alameda and Contra Costa counties on their way to inspect progress on Pit 3. This special would be the first passenger train to operate over the new line, which the report stated then ended at the dam site but would soon be extended down the river to the power house site. The story reported that PG&E had two shifts of men working in the tunnel extending 20,000 feet through two mountain ranges. Constructing Pit #3 also consumed vast quantities of materials. During the year 1924 the McCloud River Railroad recorded a total of 1,232 carloads interchanged to the Pit River Railroad, including 330 cars of machinery, iron, and pipe; 308 cars of cement; 186 cars of ties and timbers; 93 cars of petroleum products; 30 cars of lumber; 25 cars of hay; 5 cars of flour; 4 cars of grain; 5 cars of coal; 1 car of stone; 10 cars of rails and fastenings; 3 cars of brick, lime, and plaster; 10 cars of fruits and vegetables; and 222 cars of other products. The traffic consigned to PG&E inflated the inbound tonnage handled by the railroad from 5,611 tons in 1919 to 47,278 tons in 1924. PG&E placed the power plant in operation on 15 July 1925. A special train carried many distinguished guests from Sacramento to the Pit #3 dam for the dedication ceremony. The utility named the reservoir impounded by the dam Lake Britton after John A. Britton, a long-time Vice President and General Manager with the utility. Lake Britton inundated one small community, Peck's Bridge, which had been a cluster of houses, a few businesses, and a few small farms around a bridge crossing the Pit River. In the end the dam measured 494 feet across and rose to a height of 130 feet. Lake Britton has a gross maximum storage capacity of 41,877 acre feet.

Common Carrier Operations

The right-of-way grants Red River issued allowing the railroad to cross its land stipulated no common carrier service could be offered. However, when Dwight M. Swobe succeeded J.H. Queal as president of the McCloud River Railroad in 1921, Swobe made establishing common carrier service one of his highest priorities. The railroad's line to Pit 1 ended only a few miles short of the Fall River Valley, which had long sought rail transportation, and also passed near vast deposits of diatomaceous earth. Swobe opened negotiations with Red River, who indicated it did not oppose allowing common carrier service on the railroad, and the McCloud River soon gained approval to start handling carloads for parties other than PG&E. However, these efforts generated only two traffic sources of any consequence. The diatomaceous earth deposits first attracted the attention of a Chas O. Willis of Weed, California, shortly after the turn of the 20th century. Willis started location work on the deposits about 1906, but he could do very little with them until decent transportation arrived. The Pit River Railroad finally provided that transportation; in 1921 Willis started filing mining claims, and in February 1922 he joined with a fellow Weed businessmen Bruce Clark, W.J. West, A.C. Rockwood, Emory E. Smith, R.S. Taylor, Geo. A. Townes, T.W. West, Read McCreancy, M. Percell, C.H. Lion, and W.E Tebbe to incorporate the Mt. Shasta Silica Company. One source indicates Carl Phelps, a prominent Burney businessman, may have also played a role in the company, though he is not listed among the names of company officials. The details of starting the company and obtaining rail service stretched out over a year, and in March 1924 the company announced that satisfactory arrangements had been made and construction of a plant capable of processing 100 tons of diatomaceous earth each day using an air-blown filtering process would commence on the 15th of the month, with a 500-ton plant to be built at a later date. Mine claim records show the bulk of this company's operations were located a couple miles downstream from the Pit 3 dam, though the company reportedly also worked some other surface deposits around the shores of Lake Britton, including several in the vicinity of the current Dusty Camp campground. Mt. Shasta Silica conducted sporadic operations through a few years in the middle 1920s before failing, though topographic maps continued to show a “Mt. Shasta Silica Company Camp” on the divide between Rock and Screwdriver Creeks well into the 1930s. Subsequent efforts to mine the diatomaceous earth deposits would prove much more successful. In 1923, the Pit River Railroad constructed a short branch to the north end of Cayton Valley to reach the other traffic source, a new sawmill built by Harry Horr. The Horr family had a long history of operating several small sawmills and ranches in the Fall River Valley area. Horr built the sawmill primarily to cut lumber and construction timbers for PG&E. The Horr mill was the first one in the area powered by electricity, provided by a power line built from the Pit 3 dam site. Horr also built a camp including a store and a cookhouse to house and feed his employees.

PG&E Equipment

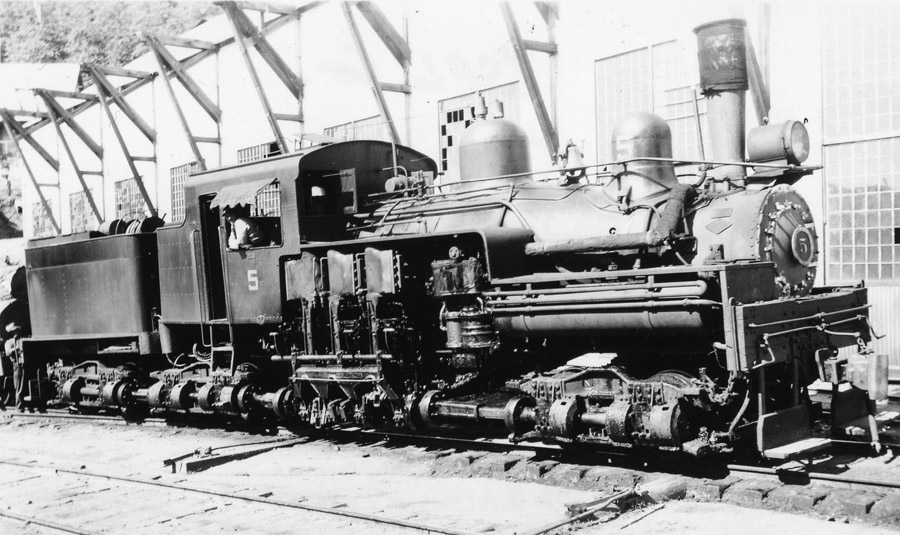

Towards the end of 1923, PG&E decided to take over operations of at least part of the Pit River railroad for itself. PG&E utilized narrow gauge construction railroads in each of these projects and brought in several small steam locomotives and at least one small Plymouth-type gas mechanical switcher as motive power, but had leased almost all other standard-gauge motive power and equipment from the McCloud River Railroad. In 1924, the Mount Shasta Power Corporation purchased two new steam locomotives, a 2-6-2 Prairie type from Baldwin assigned the #4 and a 3-truck Shay-type geared locomotive from Lima assigned the #5. The utility also picked up off the used market at least one small standard gauge 0-4-0T tank locomotive for use on the project. Rolling stock acquired by the utility included several ex-Great Northern ore jennies and a number of boxcars and flatcars. PG&E purchased the jennies from Hyman-Michaels, a Chicago-based equipment dealer that purchased the hoppers from GN and then re-sold them to other operations, primarily shortline and industrial railroads, all over the nation. PG&E acquired at least one small railbus to provide passenger service over the line. Three gasoline powered speeders handled much of the maintenance-of-way duties.

Pit 4 and 5

PG&E's original development plans for the Pit River project called for two more hydroelectric projects downstream from Pit 3. Pit 4 would have a similar setup as Pit 3, but with a slightly smaller dam and much smaller reservoir feeding a four mile long tunnel to a surge chamber, penstock, and powerhouse. Total planned production capacity of this project amounted to 107,200 horsepower. Pit 5 was the most ambitious of the Pit River projects, as initial plans for it included another small dam and reservoir immediately below the planned Pit 4 powerhouse, along with seven miles of tunnel and a power house with a total capacity of 253,600 horsepower. As work on Pit 3 wrapped up, PG&E broke ground on the Pit 4 dam. The utility extended the Pit River Railroad another four miles to reach the dam site. PG&E commenced building the dam shortly after Federal energy regulators licensed the dam on 3 August 1926 and completed it by late 1927. PG&E completed surveys to extend the railroad downstream to the Pit 4 powerhouse site; however, slacking electricity demand as the depression approached coupled with a large number of hydroelectric projects completed around the state eliminated the immediate need for more electricity from the Pit River. PG&E deferred plans for both the Pit 4 powerhouse and the entire Pit 5 project.

Abandonment

The Pit River Railroad received its first cutback in late 1927/early 1928 when PG&E abandoned the Bartle-Bear Flat stretch over Dead Horse Summit in favor of a new connection with the McCloud River Railroad established at Pondosa, which lay not too far off of the line. A new transmission line fed by the Pit 3 powerhouse supplied Pondosa with electricity. Operations over the railroad trailed off to nearly nothing following completion of the Pit 4 dam. PG&E suspended operations over the railroad and removed all of their equipment from the property by around the end of 1929. The Horr mill moved to Pondosa, and no other traffic existed in enough quantity to warrant continued operations of the railroad. The line lay idle for several years until PG&E finally abandoned the railroad in the spring of 1934. PG&E sold the rails for export to China, and in mid-April 1934 the utility brought in a small fleet of trucks to transport the rails out as scrapping crews picked them up. PG&E trucked twenty carloads worth of rail to Bieber, where a motorized derrick loaded them onto Western Pacific flatcars for the trip to the port. The trucks took the rest of the rails to Pondosa to be loaded on flatcars provided by the McCloud River Railroad. During its life the railroad hauled 350,000 tons of freight and cost approximately $1,335,000 to build and equip.

Addendum

Despite its relative obscurity, the Pit River Railroad played a vital role in the development of California through the roaring 1920s. Much of the original Pit River grade remains intact today, with only a few short stretches here and there obliterated by more recent development. The McCloud River Lumber Company reused substantial parts of the old grade in the 1930s on their Spurs 400 and 408 south of Pondosa, and the McCloud River Railroad later incorporated some of this grade into the Burney extension. Most of the road running from the Pit 3 dam down to the Pit 4 dam lies on the original railroad grade. When PG&E scrapped the railroad they only took the rails; ties, spikes, joint bars, and nuts and bolts can be found on many parts of the grade. Several old trestle remains can be found as well, although in rapidly deteriorating condition. One of the small steam locomotives used in the Pit River project survives today in Santa Maria, California, and the Baldwin prairie and the Shay went on to have long and productive careers before succumbing to the scrapper's torch in the mid-1950s. The dams and powerhouses the railroad facilitated construction of continue to be major suppliers of hydro electricity to the state. PG&E returned to the Pit River for several more projects after the railroad disappeared, including completing the Pit 5 project in 1944 after the economic uptick associated with the start of the World War II made that project feasible, followed by completing the Pit 4 powerhouse in 1955 and building the even larger Pit 6 and 7 projects in the mid-1960s. However, improved road access allowed PG&E to truck supplies in from Bartle and other railheads and avoided the need to rebuild the railroad. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Remains of a trestle near Clark Creek on the line from Cayton Valley to Pit 3. |

|

|

|

|

Ties on the old grade in Cayton Valley. |

|

|

|

|

|

Cuts on the old grade in the vicinity of Pit 3 dam. |

|

|

|

|

An old junk pile adjacent to the grade near Pit 3 dam. |

|

|

|

Partial Roster of Locomotives owned by the Mount Shasta Power Corporation and used on the Pit River Railroad: 4- Baldwin 2-6-2, c/n 56728, blt. 1924. Drivers 44”, cylinders 17x24, weight 125,720 lbs., b.p. 175 lbs., t.e. 23,400 lbs. Acquired new. To Key System Ltd, Oakland, CA, 1934; Oakland Terminal Railway #4, Oakland, CA, 1935; to Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe #2447 1943; to Modesto & Empire Traction #9 1944. Scrapped 4/1952. 5?- CRI&P 0-4-0T, blt. 1884. Built by Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad (Possibly #84?). To Union Sugar Company #4, San Francisco, CA; to Pacific Gas & Electric (Mt. Shasta Power Corporation Railroad); to Shanahan Brothers, Maywood, CA, 1937 (big gap between 1929 and 1937); to A-1 Iron & Metal Company, Los Angeles, CA, 1940; to Scrap Disposal Company, National City, CA, 1958; to Pacific Southwest Railway Museum, San Diego, CA, 1958, and loaned to restaurant in National City, CA, for a few years; to Short Line Enterprises in exchange for two Dardanelle & Russelville railroad coaches and moved to Jamestown, CA; to Walter Gray and two other private individuals; donated to California State Railroad Museum; sold 2009 to Santa Maria Valley Historical Society and moved to Santa Maria, California, for public display. 5- Lima 3-truck Shay, c/n 3263, blt. 8/1924. Drivers 36”, cylinders 12x15, weight 174,700 lbs., b.p. 200 lbs., t.e. 30,350 lbs. Acquired new. To Yosemite Lumber Company #5, Merced Falls, CA, 1929; to Yosemite Sugar Pine Lumber Company #5, Merced Falls, CA, 1943; to M. Davidson (Dealer), Stockton, CA, 1943; to Northern Redwood Lumber Company #5, Korbel, CA, 1945; to Simpson Redwood Company #5, Korbel, CA, 1957; to Lerner Steel Company (Dealer), Oakland, CA. Scrapped 1957. In addition, photographs show a small 0-4-0 tank locomotive #11 and a Plymouth 5- to 8-ton switcher #14, both probably narrow gauge. PG&E likely had others as well. Roster information courtesy of Martin Hansen and Cyrus Gillespie, among other sources; Information on #5 from shaylocomotives.com and Titan of the Timber by Michael Koch. |

|

|

Builder's photograph of the #4. Travis Berryman collection. |

|

|

The former Mt. Shasta Power #4 on the Oakland Terminal. Jeff Moore collection. |

|

|

The former Mt. Shasta Power #5 on the Yosemite Sugar Pine Lumber Company. Jeff Moore collection. |

|

|

This former Great Northern ore jenny is said to have once been PG&E #19. It has long been in ballast service on the Yreka Western. Jeff Moore. |

|

|

|

Calisphere, the on-line photo database of the University of California system, has a number of images featuring the Pit River project. The following links are to some of the photos. Pit 1 Powerhouse Pit 1 Powerhouse- View 2 Pit 1 Powerhouse- Overview Inside Pit 1 Tunnel Pit 3 Dam Under Construction- View 1 Pit 3 Dam Under Construction- View 2 Pit 3 Dam Under Construction- View 3 Pit 3 Bunk Houses Pit 3 Powerhouse Under Construction Pit 4 Dam |

|