The road and the railroad diverged at Ghinda. The road plunged east over the mountain side to the plains known as the "flats," "flats" because though it had some hills, the generally flat land so drastically contrasted with the mountains we had passed through from Asmara. The railway took a longer, round-about, southerly route down a long valley and then out onto the plains making for a gentler, more manageable grade.

At the bottom of the descent, we entered the wide, flat, Damas River valley. At one place the railway actually went four or five kilometers in a straight line. Several well organized farms stretched away from the tracks in both directions.

After a stop at the Damas station, we moved on clackedy-clack and soon began descending back and forth several times as we entered the area of thorny acacia shrubs and rocks around Dig Dig and beyond.

The Mai Atol (Atol River) station sat amid a small village of mud and wattle houses. A man in the station doorway held his goat by its leg to keep it from running away. Below here we rejoined the road, following it most of the rest of the way into Massawa. By this time the route was moving through rolling hills and generally flat desert waste lands below 600 feet above sea level with several kilometers to go to Massawa.

At the road's 86 kilometer marker (I don't remember the railroad's marker) a stone bridge crossed a dry river bed--nothing unusual, tens of stone bridges cross tens of dry river beds along the railroad. But this one was different. Members of some Eritrean liberation movement had blown up this bridge earlier. Being resourceful, the railroad engineers had just moved the tracks to the right of what remained of the bridge and laid them through the river bed. I suspect their thought was that whenever the once-in-ten-years rain washed the tracks out, they'd take the time to replace them. Until then they'd work quite well in the river bed. We eased into the river bed, glided past the bridge, groaned up the other side, and continued across the plain. No big deal.

The next stop was Saati, the site of an abandoned Italian fort where, in 1887, Ras Alula made an attempt to stop the Italian intrusion into Eritrea. Though that battle was successful for Ras Alula, he lost the war.

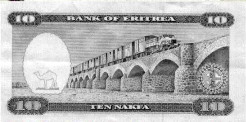

After more rocks and acacia shrubs, we came to a broad, dry river bed crossed by a long, arched, stone bridge, an impressive span--even over a river of sand. Many years later after they had won their independence and had begun to rebuild the then defunct railroad, the Eritreans celebrated their railway ingenuity on their new Ten Nakfa note: they showed a truck pulling a train across this bridge.

Train crossing the same bridge

on the back of the new Eritrean ten Nakfa note

The Littorina soon stopped at the Adi Berai station in a vast village of one-story, mostly concrete, buildings on the coast next to the Massawa islands. We stayed in the station a long time while the engineer stood around talking with other khaki-clad railroad types. The heat was oppressive (above 100 degrees) and the flies were impossible. I was very ready to go the last four or five kilometers.

Eventually, we crossed the long causeway to Talud, the first of the two islands that make up Massawa proper. Our trolley pulled into Massawa's Talud Island station, a station only a bit cleaner and spiffier than the others along the route. We left our little Littorina for a weekend in the 120-degree, dry heat of Massawa.

Later in the day we watched a small engine moving cargo around the port. Not even big enough for the engineer to stand up straight, the little engine tooted and puffed its acrid, wood smoke as it moved in and out of the Massawa port.