|

Walla Walla Valley Railway |

|

|

|

|

Walla Walla Walla Valley diesel #770 switching somewhere along the line. C.G. Heimerdinger Jr. photo. |

|

|

|

Like most modest sized American cities, Walla Walla, Washington, grew around a trolley system that provided streetcar service throughout the city. The service

started in 1905 under the banner of the Walla Walla Valley Traction Company, which in addition to the streetcar lines in Walla Walla built interurban liness to College

Place and south to the town of Milton-Freewater, Oregon. Also like most interurban operations, better roads and private automobiles cut deeply into the passenger business,

forcing the company to abandon the trolley service in 1925 and end interurban passenger operations in 1931. Unlike most interurbans, the end of the passenger operations proved to be just a closing in a chapter of the company's history. The Walla Walla Valley contains unusually productive agricultural soils, which prompted the development of a thriving agricultural industry. Union Pacific's original main line to Spokane ran through the valley, and the interurban provided the only real competition to the big road. Those competative concerns drove the traction company increasingly into the orbit of the Northern Pacific Railroad, who eventually bought the company in 1921 through the NP-owned holding company Northwestern Improvement Company. Northern Pacific immediately renamed the railroad to the Walla Walla Valley Railroad. Despite being competitors, Union Pacific and the Walla Walla Valley did build a joint branch running 4.14 miles from Milton-Freewater northwest to Umapine, Oregon, largely in anticipation of orchard development that never came to pass. The two roads abandoned that branch in 1943. The growers in the Walla Walla Valley experimented at first with various orchard tree species, most of which proved unable to deal with the harsh winter environment. The growers then turned to several vegetable crops, especially peas and sugar beets, though cherries, prunes, and apples could grow in the region. The former interurban proved an able and adept competitor to Union Pacific, especially as NP poured money into the property so that it could better handle freight cars. The shortline got the lion's share of a lot of the agricultural business in the valley thanks largely to the kind and level of service the company could offer. However, Walla Walla Valley's ability to remain competative became questionable as the 1940s drew to a close, due almost entirely to the increasing age and deteriorating condition of the freight motos and electrical system powering the railroad. Diesels were the answer, and after experimenting with a General Electric 44-ton switcher in the summer of 1949 the NP decided to sell to its subsidiary two Alco built HH660 switchers. Walla Walla Valley #770, formerly NP #DE125- arrived on 16 December 1949, followed by WWV #775, formerly NP #601 and #DE126, arrived the following May. NP found the pair underpowered for their needs, but they proved very adept at negotiating WWV's many tight curves and close clearances. |

|

|

|

|

Walla Walla Valley diesel #775 in Seattle wearing the as delivered paint scheme. Stan Styles photo, Keith E. Ardinger collection. |

|

|

|

The arrival of the two Alcos sparked Walla Walla Valley's golden age. Carloads interchanged with the Northern Pacific soared, from 2,781 in 1947 up to 3,550 in 1959. Six days

a week the WWV train crews would go on duty at the former car barn turned enginehouse near the south side of Walla Walla to start a long day of switching the numerous industries

around Walla Walla. Once those tasks had been completed the train would head south down the valley, headed for the equally numerous industries in Milton-Freewater, not to mention

the various industries scattered along the line between the two cities. One crew was sufficient to take care of the railroad's business except during the sugar beet harvest rush,

when a second crew and locomotive would be required to switch the varous beet dumps. A freeze that eliminated much of the remaining fruit tree acreage in the valley, coupled with trucks siphoning off portions of WWV's carload traffic, started negatively affecting WWV's operations as the 1960s waned. The lower traffic levels allowed WWV to retire the #775 diesel in 1968, leaving only the original diesel #770 to do all the work. The Alco era came to an abrupt end shortly after Northern Pacific merged into the Burlington Northern in 1970, as BN replaced the #770 with a pair of EMD SW-1s, the former Great Northern #77 in August 1971, followed in March 1972 by the former Fort Worth & Denver #602 that became WWV #104. Unlike the Alcos that had been painted in Northern Pacific colors but fully lettered for the Walla Walla Valley, the two EMDs wore full Burlingto Northern paint schemes with WWV sublettering. |

|

|

|

|

Walla Walla Valley diesel #770 in July 1966. G.J. Bolinsky photo, Keith E. Ardinger collection. |

|

|

|

The remainder of the 1970s were not kind to the Walla Walla Valley Railway. A shift in marketing for the largest can manufacturer shifted all of their traffic to trucks.

Grain laregly stopped moving by rail as the farmers got substantially better rates by trucking their product directly to barges on the Columbia and Snake rivers. The shift

from sugar to corn syrup in the food industry caused the sugar factories in the region to shut down and eliminated the sugar beet traffic. Worst of all, though, was that

the physical plant was simply unable handle the ever increasing size and weights of freight cars, both due to the original 56-pound rails still in use everywhere and

the numerous sharp curves. The remaining traffic simply didn't warrant the major rebuild the railroad would require to remain competative, and the railroad's very nature

of running along the sides of some streets or down the middle of others and wrapping around buildings and all of the other legacies of being a former interurban rendered

most upgrades impractical anyway. The railroad handled only 163 loaded cars in 1982 and operated to Milton-Freewater only 165 days in 1982, followed by only 50 trains run

south into Oregon in 1983. Burlingto Northern determined the railroad served no further purpose, and the ICC granted the railroad's abandonment petition on 19 April 1985. BN

formally abandoned the Walla Walla Valley on 26 Mary 1985. Very few traces of the Walla Walla Valley remain in existence today. The largest remnant is the former carbarn and enginehouse, which is now home to the Canoe Ridge Vineard tasting room and other facilities. The winery has left Walla Walla Valley Railway signs up on the building to honor its history. Elsewhere some rails are still in streets in Walla Walla, and a few other buildings from the railroad still stand elsewhere, such as the freight depot in Milton-Freewater. The former WWV diesel #770 also still exists in the collection of the Northwest Railway Museum in Snoqualmie Falls, Washington. |

|

|

|

|

BN/WWV #104 in front on the enginehouse in Walla Walla in September 1978. Keith E. Ardinger photo. |

|

|

|

|

Former Walla Walla Valley #770, now owned by Railco Leasing, in Portland, Oregon, in 1973. The Port of Longview in Washington subsequently purchased the locomotive, and it remained there until moved in 2021 to the Northwest Railway Museum grounds. Keith E. Ardinger photo. |

|

|

|

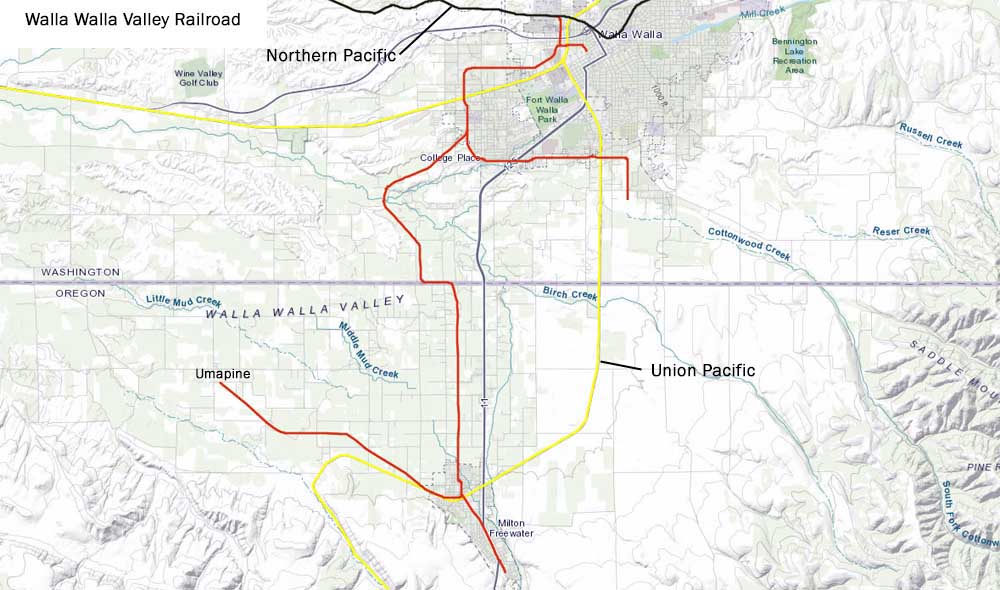

Map  |

|

|

Walla Walla Valley Railway Photographs A day with Alco #770 The Burlington Northern years |

|

|

|

References Principal reference for most information on this page is "Walla Walla Valley: 1968" by Blair Kooistra and Marc Entze that appeared in the December 2004 Trains magazine. |

|

|