|

Union Pacific Mainline- Oregon Short Line/Oregon Railway & Navigation Company |

|

|

A Union Pacific freight in the Blue Mountains. John Henderson photo, Jeff Moore collection. |

|

|

|

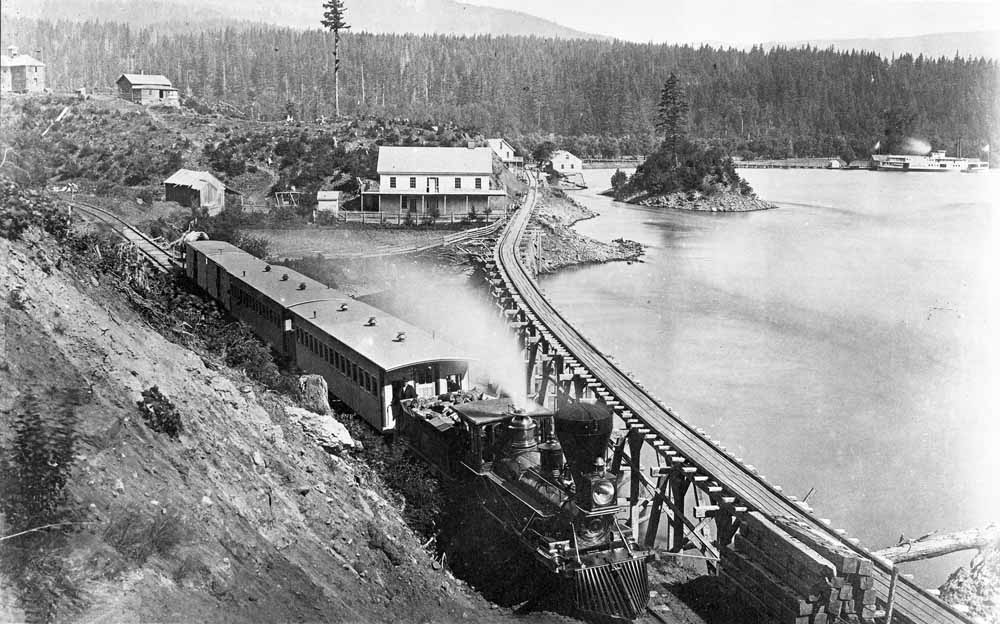

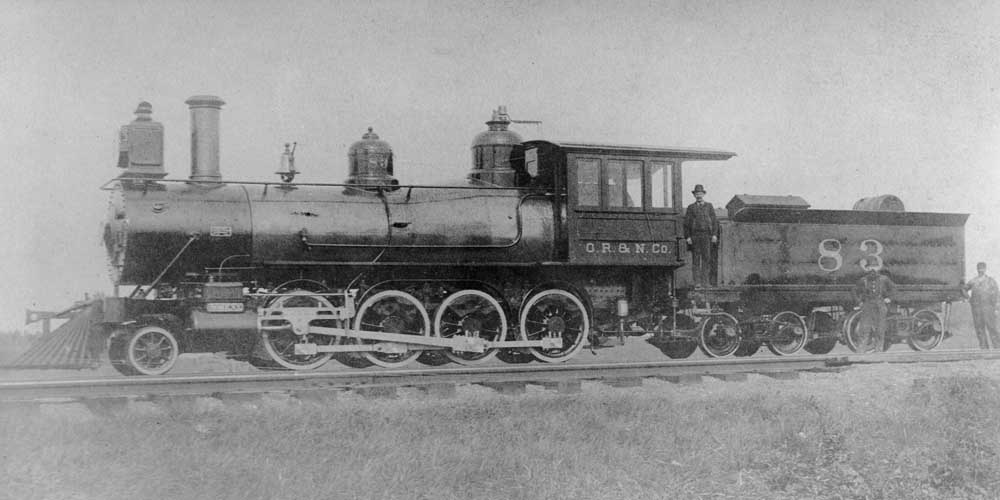

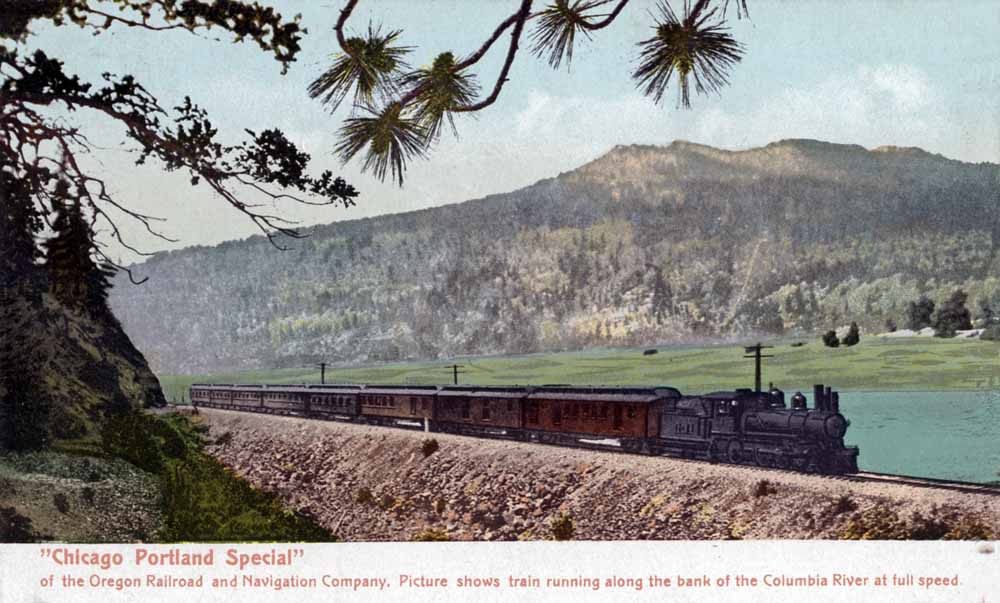

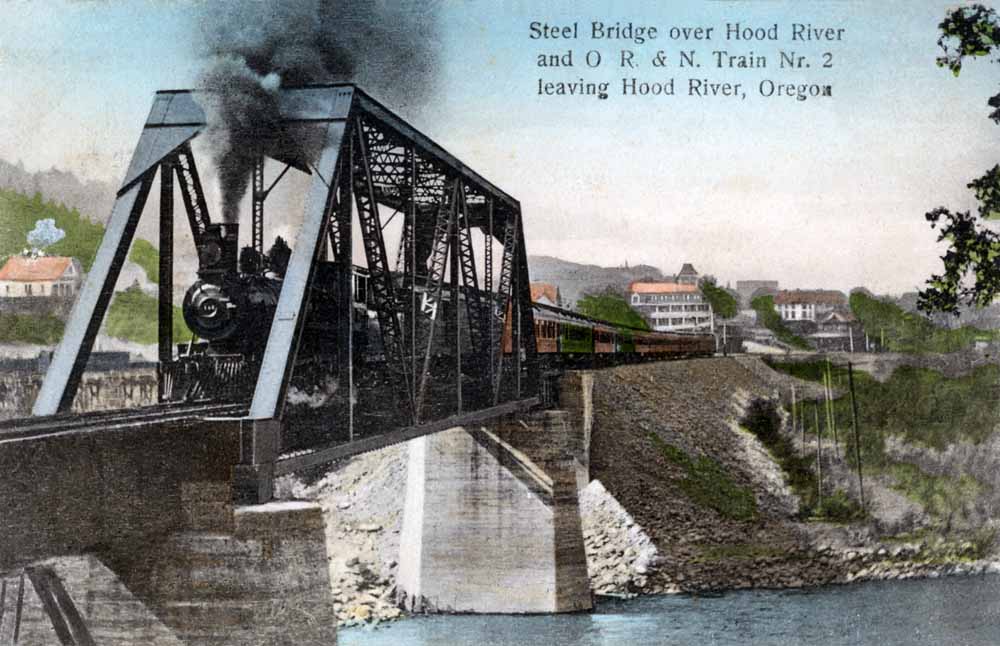

The Columbia River and its many tributaries have always been the lifeblood of both human societies and

the natural world in the Pacific Northwest. Both the Native American and early European societies

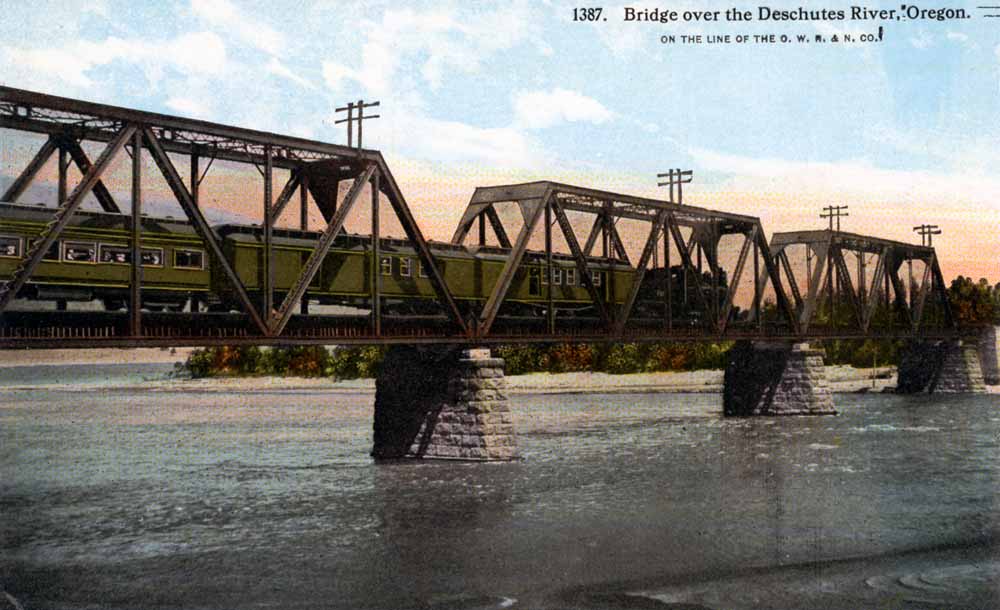

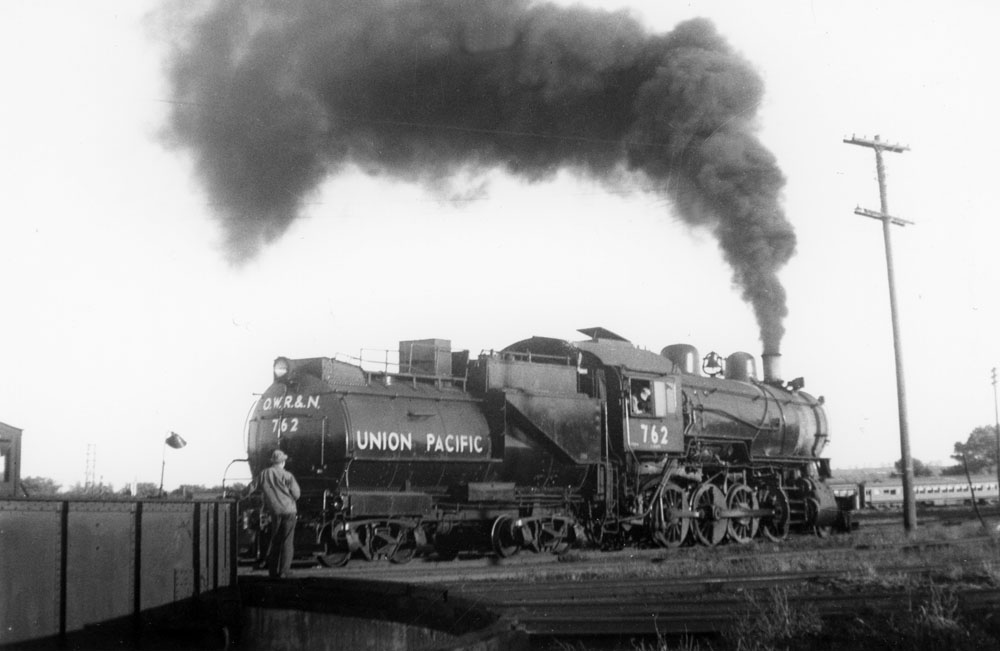

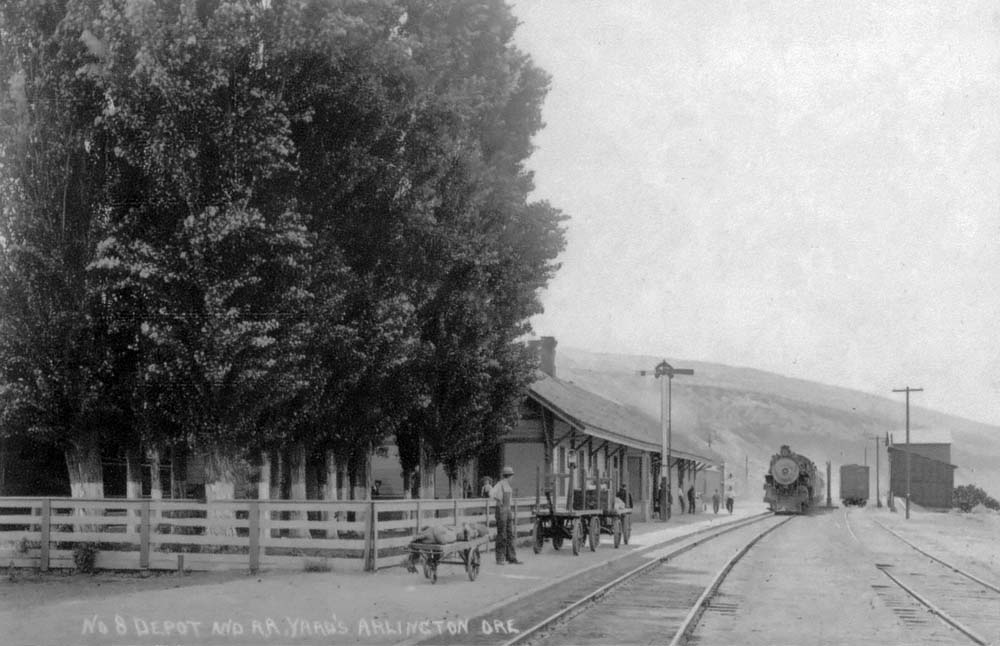

relied on the massive river for transport and trading. However, two natural sets of rapids and

waterfalls, the Cascade Rapids at what the native communities named the Bridge of the Gods and

then Celilo Falls farther upstream, effectively severed the river into three navigable segments

as Europeans introduced ever larger boats to further the commerce of the expanding settlements

in the upper reaches of the river. The two obstacles to navigation increasingly became bottlenecks as trade increased, and efforts to improve transportation on the river started in 1851 when F.A. Chenoweth built a short portage railroad, using wooden rails and mule drawn carts, around the Washington side of the Cascade Rapids. A W.R. Kilborn built a crude wagon road around the rougher Oregon side of the river by 1855, and then in 1858 he sold the road to Joseph S. Ruckel and Harrison Olmstead of Portland. Ruckel and Olmstead improved and extended the Oregon road, converting it to a wooden rail and mule powered railroad in the process, and then in 1862 they set up the Oregon Portage Railroad to manage the property. The Oregon Portage Railroad promptly purchased a small five-foot gauge 0-4-0 tank locomotive built by the Vulcan Iron Works in San Francisco, California, which became the first steam locomotive to operate in Oregon when it entered service on 10 May 1862. The locomotive quickly got tagged with the name The Oregon Pony.  The Oregon Pony remained in Oregon from 1862-1866 on the Oregon Portage Railroad and then as backup power on the Celilo railroad, then it returned to San Francisco to be used in construction work. The locomotive returned to Oregon in 1905 for display at the Lewis & Clark Exposition, then remained on display in Portland for many decades. It is now on display at Cascade Locks, Oregon. Jeff Moore collection. Captain John C. Ainsworth and his partners incorporated the Oregon Steam Navigation Company in 1860, which purchased the Bradford portage railroad in May 1862 and then the Oregon Portage Railroad later that year. The former Bradford railroad was the better of the two operations, which caused OSN to improve it by 1863, at which point the old Oregon Portage Railroad fell into disuse. Meanwhile, the OSN built a second five-foot gauge portage railroad from The Dalles east to a point above Celilo Falls on the Oregon side of the river by early 1863. Ainsworth had started the OSN with the express goal of controlling all commercial river traffic on the Columbia, and the portage railroads were a companion to the main business centered around running riverboats up and down the river.  Oregon Steam Navigation Company's Cascade Railroad replaced the former Bradford Railroad along the north bank of the Columbia River. A Cascade Railroad train is seen here preparing to depart the Upper Landing in July 1867. In the background is the OSN sidewheel steamboat Oneonta, one of OSN's regular boats assigned to the middle section of the river between Cascade Rapids and The Dalles. Carleton Watkins photo, Jeff Moore collection. All parties involved recognized it would only be a matter of time before a railroad would be built along the Columbia River. The Northern Pacific already had Congressional authorization to build a railroad down either bank of the Columbia River, plus a more direct route over the Cascade Range, and by 1871 it had pushed its mainline west into North Dakota and had started a second line north from Kalama, Washington, across the river from Portland. The Union Pacific also was contemplating a line down the Columbia to Portland. Ainsworth sold control of the OSN to the Northern Pacific in May 1872. However, the NP quickly succumbed to financing problems, and the resulting bankrutcy gave Ainsworth the opening he needed to repurchase control. By this point the Union Pacific was also getting serious about its plans involving the Columbia, setting up a potential confrontation between the two major companies. Ainsworth knew neither company would want to buy his riverboat operations, and instead in 1879 he sold the OSN company to northwest transportation magnate Henry Villard, who had the resources to play the two big railroads off against each other. Villard had been considering building a railroad along the Columbia since 1876, and on 13 June 1879 he incorporated the Oregon Railway & Navigation Company to turn those thoughts into reality. Villard folded the OSN into the new company. One of other properties Villard acquired was the Walla Walla & Columbia River Railroad, which operated a narrow gauge railroad running east into productive agricultural lands from the river at Wallula, Washington. Villard initially planned to build a narrow gauge railroad along the river, but quickly realized that the only way to fend off a competing line from either the NP or the UP would be to build the planned line to standard gauge. Grading work began at several points along the Wallula to The Dalles stretch in January 1880, and in February the company converted the Celilo portage railroad and its equipment from five foot to American standard gauge. To expedite wheat harvest shipments Villard had the WW&CR extend its narrow gauge trackage on the completed grade from Wallula to Umatilla in the late summer of 1880. The narrow gauge operations lasted until 16 April 1881, when the OR&N converted the line to standard gauge. This was the final link in the Wallula to The Dalles railroad.  OR&N Consolidation #83. Jeff Moore collection. The early 1880s proved to be busy and complicated years for railroading the region. The Northern Pacific in 1873 had settled on Tacoma, Washington, as its intended West Coast terminous. However, NP's main line building west had stalled out at the Missouri River, though the company had completed its line connecting Kalama and Tacoma, Washington, and had at least started another line going north and east from the Snake River twelve miles north of Wallula. On 20 October 1880 Villard and the NP signed an agreement allowing the NP and OR&N to interchange traffic at Wallula, along with stipulations that the two roads would split their territories along the Snake River. Villard remained very aware that the NP still had the authority to build along the Columbia and therefore remained a major threat to his enterprises, and when the NP announced in 1881 it had secured $40 million to further its construction he launched a fundraising campaign of his own that netted him enough money from investors to allow him to purchase control of the NP. Villard then turned to the task of both completing the NP main line between Wallula and Duluth and pushing the OR&N west from The Dalles to Portland. The OR&N completed its line with a silver spike celebration at Bonneville on 4 October 1882. The NP finally completed its main line with a grand gold spike celebration at Gold Creek, Montana, on 3 September 1883, and the OR&N became part of a transcontinental railroad.  An early postcard view of OR&N's Chicago Portland special along the Columbia River. Jeff Moore collection. Meanwhile, the Union Pacific finally moved on its long running plans to build a line to the northwest. In 1881 the UP incorporated the Oregon Short Line, with a charter calling for it to build a main line from Granger, Wyoming, to Baker City, Oregon. OSL rapidly pushed this line into southern Idaho, which forced Villard to start pushing a line southeast to block this latest threat to his holdings. OR&N construction crews started building southeast from Umatilla in February 1881, and the new Mountain Division line opened to Pendleton on 31 August 1882. The OR&N and OSL had initial discussions about joining their lines, but relationships deteriorated and by late 1882 the two companies were threatening to build past each other. However, both came to their senses and signed an agreement on 23 February 1883 agreeing to connect their railroads at Huntington, Oregon. The OR&N continued pushing its railroad southeast, reaching Meacham, Oregon, on 3 October 1883. This is where things stood when Villard's empire imploded. Both the OR&N and especially the NP ended up costing far more to build than initial estimates, which put both railroads on extremely shakey financial ground. Bond and stockholder actions forced Villard to resign from both companies on 17 December 1883. The OR&N stock and bond holders then took charge. One of their first primary objectives was completing the Mountain Division line, and the OR&N spiked the final rails connecting their line with the Oregon Short Line at Huntington, Oregon, on 25 November 1884.  Oregon Short Line's bridge across the Snake River straddling the Oregon-Idaho border just east of Huntington.  An early postcard view of Huntington, Oregon. The extensive rail yards are just out of view to the left. The OR&N thus started handling traffic for both of the transcontinental railroads the company had long feared, and the new directors attempted to lease their railroad to one or both of them with little initial interest. Following Villard's departure the Northern Pacific decided one route west from Wallula would be enough, and they preferred the more direct route going west over the Cascades rather than any line along the Columbia. The NP started construction on this line in early 1884, and completed it through to Tacoma in 1887, though operations were hampered by the temporary line built across the top of the Cascades until the construction forces could complete a long tunnel under Stampede Pass in late May 1888. Despite this, the NP continued negotiations around a potential lease of the OR&N until 1886. By this point relations between the various railroads had substantially deteriorated, especially as both the NP and OR&N accused each other of violating the 1880 agreement splitting their territories along the Snake River. UP by this point had become very interested in using the OR&N to build into eastern Washington, which led to a complete breakdown in negotiations between the two big railroads. This cleared the path for the UP, and on 25 April 1887 they officially leased the OR&N, retroactive to the first of the year.  Postcard view of OR&N's Train #2 crossing the Hood River.  A Union Pacific passenger train at the Huntington depot.  A postcard view of the Huntington yards, roundhouse, and depot. UP's control of the OR&N survived various corporate machinations over the next several years, and by 1891 UP owned sixty percent of OR&N's stock through its Oregon Short Line & Utah Northern Railway subsidiary. The Union Pacific then aggressively pushed a network of main lines and branchlines north and east into Washington and Idaho, along with branchlines in Oregon covered on this site. However, the Financial Panic of 1893 forced Union Pacific into bankruptcy, and in the resulting reorganization the company lost control of both the Oregon Short Line and the OR&N. The OR&N became an independent carrier again after the courts terminated its lease to the Union Pacific in the summer of 1894. By this point the OR&N's finances had become so entangled with those of so many others that the company decided it needed a new start, and on 18 August 1896 the OR&N vanished into the newly organized Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company. The new ORR&N once again found itself a pawn between what had now become three giant railroads, the UP, the NP, and the newly arrived Great Northern Railway. James Hill, the "Empire Builder" who had pushed the GN from the Twin Cities west to Seattle, strongly favored that the ORR&N should remain independent, and in 1897 and 1898 he tried orchestrating a joint control arrangement for the road between the UP, NP, and GN. However, Edward Henry Harriman shot this down when he got control of the Union Pacific in 1898. Harriman focused instead on rebuilding UP's interest in the northwest, and to that end he was able to repurchase control of the Oregon Short Line in 1899, and then in early 1900 Harriman secured a controlling interest in the ORR&N as well.  Builder's photo of the Oregon Short Line #975, a "Harriman Standard" consolidation. Following Harriman's death on 9 Septemeber 1909, the Union Pacific decided to simplify the corporate structure Harriman created. To that end, the UP merged the ORR&N and a host of other companies mostly created to build various railroads into the Oregon-Washington Railroad & Navigation Company. Under the arrangements then set in place, the Oregon Short Line and O-WR&N became independent corporations and operations, though fully controlled by the Union Pacific. Equipment each company owned was initially lettered for that company, though throught time almost all equipment got relettered for Union Pacific with smaller sublettering identifying to which subsidiary the property belonged. This arrangement lasted until 1936 when UP instituted a "System Lease" arrangement under which the road's four large operating subsidiaries, including the OSL and O-WR&N, would be permanently leased to the UP. The subsidiaries would still exist and remain legal owners of the real estate, while the UP would directly operate all the lines. This situation persisted until 30 December 1987, when the subsidiaries were finally directly merged into Union Pacific.  Early postcard view of a UP passenger train on the bridge over the Deschutes River.  Union Pacific Consolidation #762 shows its sublettering for the O-WR&N. Jeff Moore collection.  A postcard UP published about its Oregon operations. Jeff Moore collection.  A lineup of power at the La Grande roundhouse. Jeff Moore collection.  A UP passenger train stopped at the Biggs depot.  UP's depot at North Powder, Oregon.  UP's depot at Arlington, Oregon.  UP #3651 at Huntington.  UP #7013 at Hinkle, Oregon, in 1952. The various main lines built by the OR&N and OSL thus became Union Pacific's important main line connecting Portland with the rest of the railroad's system, and it remains a heavily used railroad today. Amtrak's Pioneer operated over the route until discontinued in 1997.  An eastbound freight at Arlington, Oregon, in 1991. Keith E. Ardinger photo.  A UP local working in Cascade Locks circa 1990. Jeff Moore photo.  Union Pacific GP38-2 #2029 at The Dalles in 1996. Keith E. Ardinger photo.  An eastbound freight at Memaloose. Note the mouth of an abandoned tunnel replaced by a large cut to the right of the train. Jeff Moore photo.  A westbound freight passing through Huntington, Oregon. Jeff Moore photo. |

|

|