We walked from Greenfield Village towards the Henry Ford Museum where I spotted this.

Henry Ford (1863-1947) statue near the front entrance of the Museum, after which we walked into the museum and I was surprised at what I first saw.

This DC3 was built by the Douglas Aircraft Company in 1939. This model, introduced in 1936, carried 21 passengers, enough to fly profitably without relying on subsidies from air mail contracts. While the DC-3's economy appealed to airlines, its rugged construction and comfortable cabin attracted passengers. More than any other aircraft, the DC-3 ushered in the era of dependable, long-distance air travel in the United States. This particular airplane logged more than 12 million miles and was aloft for 83,032 hours over nearly nine-and-a-half years.

Looking down towards the right I could see the Chesapeake and Ohio Allegheny locomotive and made my way there.

On the way there I passed some of the cars on display.

1967 Ford Mark IV Race Car. In the 196'0s, Ford Motor Company made the most massive sports car racing effort ever seen in America. The objective was to beat the dominant Ferrari team in the world's most important sports car endurance race — the 24 Hours of Le Mans. The weapon was a family of cars best known as the Ford GT40. Ford’' first of four straight victories, in 1966, was won by the GT40's Mark II variant, fielded by the Shelby American team and driven by New Zealanders Bruce McLaren and Denny Hulme. The next year, Shelby returned with this car—the more powerful Mark IV. Its chassis was built of an aluminum honeycomb material used in aircraft construction, and the body shape resulted from hours of wind tunnel testing. The big 427-cubic-inch V-8 engine was based on Ford's stock car racing engine and proved highly reliable. Drivers Dan Gurney and A.J. Foyt beat the second-place Ferrari by 32 miles at a record-breaking average speed of 135.48 mph. That win was another first at Le Mans because, unlike the year before, the winning car was built in the United States. This was the first Le Mans win by an American car, built in the United States and driven by Americans.

Lamy's Diner. A menu not just created but curated to drop you into 1946 New England with delicious authenticity. Lamy's Diner sits smack in the middle of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, with period menus, paper straws and an iconic counter. But the truest testament to the times are the dishes served with '40s friendliness. Chicken salad sandwiches and frappes (the original Northeastern milkshake) are prepared in their original style. A slice of today's pie, a Faygo float or a melty Toll House cookie with walnuts will sweeten your visit. Sweets, lunch and a kids' menu make Lamy's Diner a swell stop any time of the day.

"Dewitt Clinton" is a replica built in 1893 by New York Central for that year's Chicago Worlds Fair. It appeared at the 1927 Fair of the Iron Horse in Maryland and was used for promotional purposes by the railroad until loaned to the museum in 1935. It appeared at the 1933-34 Chicago World's Fair, 1939-1940 New York World's Fair and the Chicago Railroad Fair in 1948-1949.

The original was designed by John B. Jervis and built by David Matthew at the West Point Foundry for the Mohawk & Hudson in 1831. It was the M&H's first locomotive (until then, trains had been pulled on the sixteen mile line from Albany to Schenectady by horses), the first to operate in the state of New York and only the fourth steam locomotive built in the US. Shipped to Albany by river boat, it made its debut at a celebration to mark the opening of steam operations on the line.

Named after the US Senator and sixth Governor of New York who was largely responsible for construction of the Erie Canal, the original locomotive apparently weighed 6,750 lbs. Designed to burn anthracite coal, the 0-4-0 apparently drew" badly and did not produce sufficient draft to develop the heat necessary to power the engine. It was consequently converted to burn wood.

The replica at the museum is displayed much as it would have appeared at its inauguration on 9th August 1831, pulling a car carrying water barrels and three passenger carriages made of stagecoach bodies attached to railroad trucks. These were standard passenger conveyances of the day, although soon superseded by purpose built passenger carriages.

Chesapeake and Ohio 2-6-6-6 1601 built by Lima Locomotive Works in 1941. Designed to work over the Allegheny Mountains on the railroad's Clifton Forge Division, the locomotives were named "Alleghenies" and this is one of only two to survive.

The Alleghenies usually doubled on the most challenging part of the grade, one at the front and one at the back, typically pulling one hundred car coal trains eastbound from Hinton, West Virginia, to the top of the grade at Alleghany (a local spelling). With a loaded coal car nominally weighing 100,000 lbs, that totals a staggering 10,000,000 lbs or nearly 4,500 tons! The locomotives had a relatively short operating life and started going into storage in 1952 as diesels began to take over on the system. The last fires on an Allegheny were dropped at the Hinton engine terminal on 27th July 1956. 1601 was donated to the museum in that year.

Elizabeth and I in front of Chesapeake and Ohio 1601.

The author at the throttle.

In 1929, Ford had this replica of the "Rocket" built by Robert Stephenson & Company, in Darlington, England at a cost of $11,913.60. The greatly-altered original, built in 1829, is now on display in the Science Museum in London.

The original 0-2-2 "Rocket" won Stephenson £163,500 at the three day Rainhill trials, set up by the Liverpool & Manchester Railway to determine the best motive power to employ on the railroad. Ten locomotives were entered, but only five competed. The "Rocket" was the only one to complete the trials, starting on 6th October 1829, averaging 12 mph and achieving a top speed of 30 mph. Stephenson was consequently awarded the contract to build locomotives for the Liverpool & Manchester, and the horizontal boiler and rear firebox, multiple boiler flues and directly connected driving rods pioneered by the "Rocket" were employed on virtually every subsequent steam locomotive.

Atlantic and Gulf 4-4-0 3 "Satilla" built by Rogers Locomotive Works in 1858 to work at one of its logging plants. It was one of the first locomotives bought by the railroad and was named "Satilla" after the river of that name. Chartered in 1856, the Atlantic & Gulf crossed southern Georgia from Thomasville to Screven, where it connected with the Savannah, Albany & Gulf Railroad on to Savannah. The two railroads were consolidated in 1863.

The "Satilla" was sold to the Savannah, Florida & Western Railway in 1879 and, ten years later, to the J.J. McDonough Lumber Company. Re-numbered 110, it worked for the next thirty-five years at McDonoughs until it was purchased by Ford in 1924. He then renamed it "Sam Hill" in honour of an engineer who had worked on a Michigan Central express that passed through Dearborn when he was a boy. Ford loaned the locomotive to appear at the 1927 Fair of the Iron Horse in Maryland. He then donated it to the Edison Institute in 1928, where it was renamed "The President" in honour of President Herbert Hoover when it was chosen to haul a set of specially built cars to the opening of the Institute.

The Edison Institute, of which the Henry Ford Museum forms a part, was dedicated by President Hoover on 21st October 1929 on the 50th anniversary of Thomas Edison's invention of the incandescent light bulb. Amongst luminaries in attendance were Marie Curie, John D. Rockefeller and Orville Wright, and Hoover's dedication speech was broadcast on national radio, with listeners encouraged to turn off their electric lights until the switch was flipped at the new museum.

Fruit Growers Express 40 foot refrigerator car 55667 built by the company in 1924.

Canadian Pacific wedge snow plough 40850 built by the railway in 1923. It was designed to clear snow from single tracks, throwing snow off to each side as it was pushed forward by one or two locomotives attached to the rear. It worked in Canada and New England from 1923 to 1990, when it was donated to the museum by the Canadian Pacific.

The movable "wings" could be opened to extend the plough's operating width from 10 feet to 16 feet across. Snow ploughs were essential parts of the maintenance-of-way equipment for railroads operating in the snow bound north.

Bessemer and Lake Erie 2-8-0 154 built by Baldwin in 1909. Four Consolidation locomotives were built for the Bessemer & Lake Erie by the Pittsburgh Locomotive Works in 1900 but 154 was one of six more acquired in 1909 from Baldwin. The primary business of the Bessemer & Lake Erie was hauling heavy tonnages of iron ore and coal between the industrial area of Pittsburgh and the Lake Erie ports of Conneaut, Ohio and Erie, Pennsylvania. When originally built, this class of "drag" Consolidation was the heaviest and most powerful locomotive in the world. They were specifically designed to tackle the heavy grade between Conneaut and Albion, Pennsylvania.

154 spent its forty-four year operating life on the Bessemer & Lake Erie before retiring in 1953 and being held for potential donation to a museum. It waited a long time, however, as it was not until 1984 that it was donated to the Illinois Railway Museum in Union, Illinois then five years later, it was traded for Detroit, Toledo & Ironton 16.

What would eventually become the Bessemer & Lake Erie route started with the Shenango & Allegheny Railroad in 1869. The Pittsburgh, Bessemer & Lake Erie Railroad was then founded in 1897 by Andrew Carnegie. Created from a set of smaller railroad companies including the Shenango & Allegheny, it was renamed the Bessemer & Lake Erie in 1900 and was then acquired by US Steel when that company bought Carnegie Steel in 1901 as part of a major consolidation. In 1988, the Bessemer & Lake Erie became part of Transtar Inc., a privately owned transportation holding company. In 2001, the railroad then became part of the Great Lakes Transportation holding company and in 2004, joined the Canadian National Railway as part of its larger purchase of Great Lakes Transportation.

General Electric Ingersoll-Rand/Alco 90 built in 1926. From 1925 to 1930, a partnership of Alco, General Electric and Ingersoll Rand produced a series of oil-electric and diesel-electric locomotives. 90 is the sixteenth unit produced by the partnership. Alco issued orders and provided the car bodies to General Electric at its Erie works. Ingersoll-Rand produced the engines in Phillipsburg, New Jersey and shipped them to General Electric, which then delivered the completed units back to Ingersoll-Rand.

Used as a promotional demonstrator, switching in Ingersoll-Rand's Phillipsburg works until the late 1960's, it was donated to the museum in 1970 and went on display in 1984.

Pullman business car "Fair Lane" built by the company for Henry Ford in 1921. Its name was the same that Henry and Clara Ford had given to their estate in Dearborn, Michigan. Fair Lane was the area in County Cork, Ireland, where Mr. Ford's grandfather was born.

The St. Louis Southwestern Railway purchased "Fair Lane" from the Fords for $25,000 and numbered it 5. The company used the car for railroad business, carrying executives on its lines concentrated in Arkansas and Texas. In 1972, St. Louis Southwestern donated "Fair Lane" to the Cherokee National Historical Society. The organization used the car as an office space for the Cherokee Nation in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Richard and Linda Kughn purchased "Fair Lane" in 1982 and they moved it to Tucson, Arizona and began a four-year project to restore the car to its original Ford-era appearance. At the same time, they updated "Fair Lane" with modern mechanical, electrical and climate-control systems. The Kughns enjoyed the refurbished railcar for several years before gifting it to The Henry Ford in 1996. Today Fair Lane is back in Dearborn — a testament to the golden age of railroad travel.

Wayne County narrow gauge 0-4-0 7, a coal-burner, built by Davenport Locomotive Works of Davenport Iowa, in 1898. It worked for Michigan's Wayne County Road Commission from 1922 to 1927.

Detroit & Mackinac combine 100 built by Barney and Smith circa 1905 and donated by the railroad in 1979.

Detroit, Toledo and Ironton caboose 77 built by Standard Steel in 1925.

Fort Collins Municipal Railway Birney Safety Car 26 built by American Car Company in 1922, ex. Midwest Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society 1951-1953, exx. Fort Collins Municipal Railway 1924-1951, nee Cheyenne Electric Railway Company 7 1922 to 1924. This car participated in a transit history parade in Detroit before being donated to the Henry Ford Museum, where it is now on static display in Greenfield Village.

Brooklyn City Railroad horse-drawn car 1 built by J.M. Jones of Troy, New York in 1881 and used on the Hunters Point and Erie Basin streetcar line.

Cleveland Railway Company streetcar 0140, ex. Cleveland Transit System 0140 1942-1954, exx. Cleveland Railway Company 0140 1916-1942, exxx. Cleveland Railway Company 1965 1910-1916, exxxx. Cleveland Electric 165 1903-1910, exxxxx. Cleveland City Railway 165 1893-1903, nee Woodland Avenue and West Side Street Railroad 165 1892-1893 built by J.G. Brill Company in 1892. It was acquired by the museum in 1954.

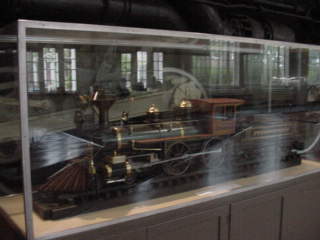

Models of Lackawanna passenger cars and a Pennsylvania Railroad 2-4-0 steam engine. Next we will look at the automobiles.