After that fantastic trip on the San Luis Central and saying goodbye to our other passengers, Chris Parker and I drove east on US 160 to Alamosa, stopping at Arby's for lunch before driving to where the San Luis and Rio Grande motive power is kept.

Line of San Luis and Rio Grande Railroad power led by former Southern Pacific B30-7 7863 built by General Electric in 1979.

San Luis and Rio Grande F40M-2F 453, ex. Canadian American 453, nee Amtrak F40PH 385 built by Electro-Motive Division in 1981.

San Luis and Rio Grande F40M-2F 459, ex. Lubbock and Western 459, exx. Texas and New Mexico 459, exx. Austin and Northwestern 459, exxx. Canadian-American 459, nee Amtrak F40PH 264 built by Electro-Motive Division in 1977.

The former Denver and Rio Grande Western Alamosa station built in 1908.

Historic St. Mary's Railroad FP10 1100, ex. New Century Rail Transport LLC 1100, ex. Indian Head Central 1100 1999, exxx. Cape Cod Railroad 1100 1992 to 1998, exxxx. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority FP10 1100, exxxxx. Illinois Central Gulf 1604 1972, exxxxxx. Gulf, Mobile and Ohio 805A, nee Alton Railroad 810, built by Electro-Motive Division in 1946.

Denver and Rio Grande Western 4-6-0 169 built by Baldwin in 1883. In 1939, the locomotive was refurbished at the Denver & Rio Grande Western's Burnham Shops in Denver, to appear at the 1939-40 New York World's Fair. In 1941, the railroad donated it to the City of Alamosa and it has been on display in downtown Cole Park ever since. It is one of the oldest surviving locomotives of the Rio Grande Railroad. Also on display is business car B-1, built by Jackson and Sharpe in 1880 as 33 "Bovincia" and re-built into a business car in 1885.

We continued east on US 160 before turning north onto Colorado 150 for a visit to Great Sand Dunes National Park. Road construction caused us some delay as we waited for an escort vehicle.

The construction lasted all the way to the park entrance.

Great Sand Dunes National ParkThe dunes were formed by the right combinations of wind, water and sediment. Creeks and streams brought in large amounts of sediment and sand into the valley. Wind then blew the sand toward the bend in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, where opposing storm winds helped squeeze the sand into the tall dunes you see today. The story of how the Great Sand Dunes were formed is much more complex and as new research discoveries occur each year, is continually evolving.

Through the breaking apart and movement (rifting) of large surface plates on Earth's surface, the Sangre de Cristo Mountains were uplifted in the rotation of a large plate. Fossils from the bottom of an ancient sea are now preserved in high layers of rock in the Sangre de Cristos, illustrating the scale of the uplift. The San Juan Mountains were created through volcanic activity. With these two mountain ranges in place, the San Luis Valley was born, covering an area roughly the size of the state of Connecticut. Sediments from both mountain ranges filled the deep chasm of the valley, along with huge amounts of water from melting glaciers and rain. The presence of larger rocks along Medano Creek at the base of the dunes, elsewhere on the valley floor, and in buried deposits indicates that some of the sediment has been washed down in torrential flash flood events.

In 2002, geologists discovered lake shoreline deposits on hills in the southern part of the valley, confirming theories of a huge lake that once covered much of the San Luis Valley floor. They named this body of water "Lake Alamosa" after the largest town in the valley. Lake Alamosa suddenly receded after its extreme water pressure broke through volcanic deposits in the southern end of the valley. The water then drained through the Rio Grande River, likely forming the steep Rio Grande Gorge near Taos, New Mexico. After Lake Alamosa drained away, smaller lakes still covered the valley floor, including two broad lakes in the northeastern side of the valley. Streams from both mountain ranges have continued to bring sand to the depressions where the lakes form. In the past, this included the Rio Grande.

Lake Alamosa, the subsequent smaller lakes and Rio Grande have fed sand to Great Sand Dunes for the past 400,000 years. The dune sand extends to depths of 300 feet below the valley floor and just above Lake Alamosa deposits, indicating that there have been dunes here since the time of Lake Alamosa. Remnants of these large lakes are still here today, in the form of sabkha (alkali flat) wetlands and playa lakes.

When the lakes periodically dry, sand left behind blows with the predominant southwest winds toward a low curve in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The wind funnels toward three mountain passes here - Mosca, Medano, and Music Passes - and the sand accumulates in this natural pocket. Sand grains are a perfect size for the winds to move. Sediment grains larger than sand are too heavy to be moved by the wind, while grains smaller than sand are light enough to be picked up and held by the wind and carried away. Sand grains on the other hand, are light enough to be picked up by the wind, but heavy enough that wind typically cannot keep them in the air, so the sand bounces along the surface of the valley floor, moving along, and gathering together in locations where the wind is slowed, or an obstacle is in the way.

Environments where wind moving sediment is the dominant process are called aeolian environments. The winds blow from the valley floor toward the mountains, but during storms the winds blow back toward the valley. These opposing wind directions cause the dunes to grow vertically, and make it difficult for the dunes to migrate into the mountains.

As time went on, the wetlands and playa lakes (lakes that grow and shrink periodically with water availability) played an important role in the formation of the dunes. Much of the sediment that had been brought into the valley from the mountains was unsorted, having a mixture of grain sizes and materials, including muds, silts, clays, and most importantly sands. These smaller bodies of water and seasonal lakes helped sort the sand from the rest of the sediment. When the lakes and wetlands are full, sand is deposited near the edges, forming little sandy beaches. As water levels lower, the sand is then exposed to wind, allowing the aeolian processes to take over. This created a continual sand source for the growing dunes for quite some time, allowing the dunes to accumulate enough sand to reach their current massive size.

Even with the opposing storm winds, most sand is still blown toward the mountain ranges. Here, two seasonal mountain streams, Medano Creek and Sand Creek, capture sand from the mountain side of the dunefield and carry it around the dunes and back to the valley floor. The creeks then disappear into the sand sheet, and the sand blows back into the dunefield. Barchan and transverse dunes form near these creeks. Water from these creeks then reappear in near the southwestern edge of the park, feeding into the wetland and playa lake systems. Learn more about the hydrology of Great Sand Dunes.

This combination of opposing winds, a huge supply of sand from the valley floor and the sand recycling action of the creeks, are all part of the reason that these are the tallest dunes in North America. There are other dunes in Colorado, and in most western states, but none as tall (741 feet) and none as dramatic. Here giant dunes rise in front of the alpine Sangre de Cristo Mountains, while streams flow across the sand seasonally, making for an unusual and unexpected sight.

Currently, there is enough vegetation on the valley floor that there is little sand blowing into the main dunefield from the valley. However, even today there are still some small parabolic dunes that originate from the playa lakes in the sand sheet and migrate across grasslands, joining the main dunefield. At other times, some of these migrating dunes become covered by grasses and shrubs and stop migrating. This limits the amount of new sand entering the main dunes system. The lack of new sand coming in suggests that the overall size of the dunefield is not growing, but the dunes within are constantly moving in complex patterns. It is possible that lots of new sand enters the dunefield when climatic conditions decrease the vegetation on the sand sheet, such as during an ice age, when it is cold or during extremely dry periods.

A sign at the front gate said to pay inside the Visitor Center so we made that our first stop in the park.

After we paid, we took a few pictures from the balcony outside the Visitor Center then drove to the Dunes parking area for a hike out onto the dunes.

Our hike started with the crossing of Medano Creek which was still covered with a light layer of snow, meaning you had to walk carefully.

Snow was still covering the lower dunes.

The dunes with Mount Herard behind.

Mount Herard, Mount Blanca, Ellingwood Point and Carbonate Mountain.

The view towards the top.

Interesting shadows in the dune field.

Chris Parker in the Grandeur of It All! We decided not to hike all the way to the top as our views this high up were incredible.

Another interesting dune view.

Looking down into the San Luis Valley was stunning.

Contrasts abound!

Mount Herard. We hiked back down to the parking lot and a bathroom stop was made before proceeding to Blanca.

Cleveland Peak.

The sand dunes really stood out against the mountains behind.

The western end of the sand dunes runs into the San Luis Valley.

While waiting for the escort vehicle, we took several pictures and more construction delays yielded a few more. We drove back down Colorado 150 to US 160 east to the little town of Blanca, our next stop.

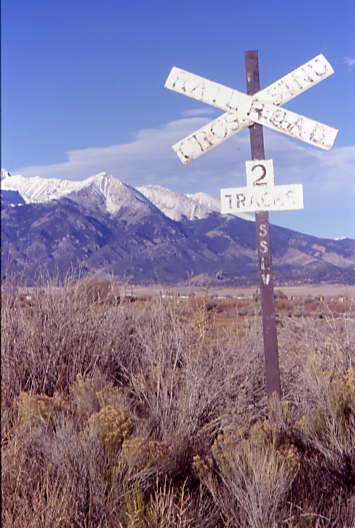

San Luis Southern: A Ghost RailroadWe turned right and the first road in town and crossed the San Luis and Rio Grande Railroad tracks, whose rails we rode yesterday, before spotting a pair of crossbucks but no rails. We parked here after we spotted the home-built locomotive of the San Luis Southern at an abandoned industrial site.

A brief historyThe railroad was incorporated July 3, 1909 as the San Luis Southern Railway and opened a rail line from Blanca to Jaroso, Colorado. The company was reorganized as the San Luis Valley Southern Railroad in 1928 and was again sold and reorganized as the Southern San Luis Valley Railroad Co. on December 11, 1953. All of the line, except the last 1.53 miles, was closed and dismantled in 1958. Operations of the SSLV ceased some time late in 1994, although the track remains in place.

Tracking a Ghost Railroad

Walking toward the engine, I soon discovered the tracks.

Next came upon a switch with the switch stand still remaining. I made my way towards the unique engine.

San Luis Southern D-500 built by the railroad from Denver and Rio Grande Western steam locomotive tender frame 964 which they had purchased in 1950 and after an abortive attempt at building a locomotive on the tender frame, a successful machine was completed in 1955. It rolled on standard locomotive tender trucks which were powered by a sprocket and chain drive. Power was from an International Harvester, 1091 cubic inch, UD24 diesel engine. The power went through a Caterpillar hydraulic transmission, which in turn powered an old Euclid truck axle, which transmitted power through sprockets and chains to the axles. The odd locomotive, which resembled a caboose, was built in a cupola style for visibility and to ease the installation of the prime mover.

Behind D-500 is the remains of Plymouth ML8, ex. Utah Power and Light, bought in 1977. The gasoline engine was removed in 1980 so that a caterpillar engine could be installed, but the work never finished, so it has remained here since. We left them to the winds of time.

Our rental car.

A crossbuck with SSLV lettering.

The remains of some of the track that once went south from Blanca. After having great success at this ghost railroad, we returned to US 160 and went over La Veta Pass to Walsenburg.

The former Denver and Rio Grande Western/Colorado & Southern station built in the 1920's.

The junction with the BNSF and Union Pacific, curving off to become the San Luis and Rio Grande Railroad. From there it was back down Interstate 25 to Trinidad.

At sunset, we exited the freeway at Trinidad.

TrinidadWe arrived at Best Western Trinidad Inn after 5:20 PM, checked in and received directions to the best restaurant in town so we followed them but could not find it. The two of us stopped at a petrol station and Chris went in to get revised directions but still we could not locate it so I decided to go into a bar on Main Street to ask. Just as I was about to enter, the power went out in most of Trinidad and I learned that the restaurant was closed on Sundays. We drove through a darkened city looking for something to eat. There were lights in the northern part of town, but no restaurants. The east side of town had nothing, but back down by the station, a MacDonald's had lights, so that would have to be it.

Chris then spotted a Shell station which had a Subway inside, where we bought some food to go. Driving back to the hotel in the dark was an adventure as we missed the driveway and a wise turn by me led us back to the hotel just as the power returned. Back inside the room about twenty minutes later, the power went out again. The only light we had been was provided by our digital cameras while we reviewed our pictures in the darkness, which made for an interesting part of the evening. The power was restored and we were watching a PBS program on African trains when that cable station was lost. A restful night of sleep was then had.

10/30/2006 After a good continental breakfast, along with television programs on the Salem Witch Trials and "Three Deadly Women" on the History Channel, we checked out and on the way to the petrol station, Chris spotted a railroad display.

This three-piece displays on Purgatoire Drive consists of Colorado and Southern 2-8-0 638 built by Brooks in 1906. Long after the rest of the road had been dieselised, the Colorado and southern continued to use steam on its Climax-Leadville branch as the thin air at the high altitude of Leadville (10,152 feet) severely hampered the operation of internal combustion engines. 638 ran a few excursions in 1962 on the Moffatt line. That year, it was donated to the City of Trinidad. Behind the steam engine are Colorado and Southern coach 545 built by Pullman in 1906 and Colorado and Southern wooden caboose 10507.

We fuelled the rental car at Shell before settling up with JJ Motors, who allowed us to drive back to the Amtrak station.

The Trinidad Amtrak station. Looking east down the tracks, I spotted a building with a Santa Fe symbol on it so went over.

The Santa Fe freight house.

The Purgatoire River which flows through Trinidad with the old Colorado and Southern bridge in the background. The Burlington Northern relocated their tracks here a few years ago to eliminate crossing the Santa Fe at grade which also eliminated long Burlington Northern coal trains cutting the town in two.

I called Julie, Amtrak's automated agent, to try to get an arrival time for the Southwest Chief and finally got the word it departed La Junta at 9:10 AM, forty minutes late. I walked over to the Shell station to get a Subway sandwich and cookies for lunch before Chris walked over there to get something for his sinuses. It was a windy morning as I sat on the station platform and Julie's ETA came and went.

The trees were loosing their leaves as autumn had taken hold here. I called Amtrak and a real agent made a call to Operations, telling me they waited on a late crew and slow orders from the blizzard the night we arrived in Colorado, but the train would be arriving shortly.

The train finally arrived at 11:46 AM {9:50 AM} with P42DCs 181, 131 and 147, baggage 1228, sleepers 32038, 32056 and 32066, diner 38039, lounge 33003 and coaches 31046, 34079 and 34134. Chris and I boarded the 34079 and after our tickets were taken, both headed to the lounge car and enjoying our sandwiches as I pointed out highlights of the crossing of Raton Pass to Chris. After Raton Tunnel, I returned to my seat and at a windy Raton, I stepped off for some fresh air.

When I had my ticket taken by my car attendant, I asked about upgrading to a sleeper. At French, New Mexico, the conductor visited me and for $167, I received Room 8 in the 331 Car (32056). My conductor helped me bring my bags from the coach all the way to my room. We passed Chris in the lounge car and I updated him as to what was going on, then listened to Jethro Tull's Extra Thick as a Brick bonus material as Glen, my sleeping car attendant, stopped to introduce himself. At Las Vegas, we made a prolonged stop then later at Chappelle, we met the eastbound Southwest Chief and I made a 6:30 PM dinner reservation.

A view below the "S" curves.

The view towards Glorieta Pass.

The train later crossed the Pecos River at the bottom of the grade. I rode in the lounge car over Glorieta Pass, Apache Canyon and past Lamy with Chris, who had a 7:05 PM flight home. I hoped and prayed the train would get him to Albuquerque with enough time to make his flight. The sun set and we made our way into Albuquerque, arriving at 5:53 PM {4:05 PM}. I beat Chris to the bus stop where I learned that the 6:07 PM bus to the airport arrived at 6:27 PM and suggested he take a cab then said my goodbyes to him. He made his flight and was home by the time I was in Winslow.

I enjoyed the fresh air before being called into the dining car at 6:20 PM for dinner. Richard Talmy, the former wonderful Parlour Car Attendant on the Coast Starlight, was my waiter and I was seated with Barbara from Alamosa and Bee and Conrad from Colorado Springs, all going to Los Angeles. We departed at 6:34 PM {4:45 PM}. The pork shanks were excellent and I enjoyed a chocolate bundt cake for dessert, along with excellent conversation. An after-dinner shower felt really good before I returned to my room for an evening of music. After Gallup, I made my bed and called it a night.

10/31/2006 I awoke just prior to Victorville, arriving there at 5:56 AM {4:08 AM} then proceeded to the dining car, with Al going to San Diego, Carolyn going to Salinas and Conrad again. The meal lasted from Victorville to Devore, so I enjoyed Cajon Pass and the sunrise along the descent into the clouds.

The French Toast and sausage were excellent and really hit the spot. After breakfast, we stopped at San Bernardino and Riverside before making the final sprint to Fullerton. At Corona, I changed into my work clothes and prepared to arrive into Fullerton, which we did at 8:22 AM {6:24 AM} and I walked over the bridge to Track 2 and left a message at home that I was in Fullerton.

The Southwest Chief departed Fullerton for its final sprint into Los Angeles Union Station.

Next, Pacific Surfliner 763 on its way to Goleta stopped while I waited for Metrolink 600 to take me to Santa Ana.

Metrolink 600 10/31/2006

The train arrived at Fullerton early and I loaded my bags into the cab car, then we stopped in Anaheim and Orange before arriving at Santa Ana, ending yet another rail adventure. Time for me to go to work!

| RETURN TO THE MAIN PAGE |