My mother and I were in the midst of our only Alaska cruise of our lives and up early as usual, I ate yet another good buffet breakfast then went to the Promenade Deck of the Sun Princess to watch the forklift move the boarding ramps into place. Twenty minutes later, I led the way off the cruise ship and into Skagway.

The White Pass and Yukon Railroad

I arrived just as three locomotives, led by CERES 140 91, were delivering a trainset to the depot. I purchased some goodies in the station before picking up my ticket to Lake Bennett and back.

I walked down to the depot built in 1898.

At the other end of the station was White Pass and Yukon rotary snow plough 1 built by Cooke Locomotive Works in Paterson, New Jersey in 1899. I walked over to my train to Lake Bennett, which consisted of DL535's 100 and 92, flat car 479, combine 211, coaches 286 "Lake Kusawa", 280 "Lake Dease", 207 "Lake Morrow" and 282 "Lake Klukshu". I rode in "Lake Morrow".

White Pass and Yukon Railroad History

Every railroad has its own colorful beginnings. For the White Pass & Yukon Route, it was gold, discovered in 1896 by George Carmack and two First Nations companions, Skookum Jim and Dawson Charlie. The few flakes they found in Bonanza Creek in the Klondike barely filled the spent cartridge of a Winchester rifle. However, it was enough to trigger an incredible stampede for riches: the Klondike Gold Rush.

The rush for riches was actually predicted by Skagway founder, Captain William Moore. He was hired by a Canadian survey party, headed by William Ogilvie who had been commissioned to map the 141st Meridian, the boundary between the United States and Canada. Because the known route, Chilkoot Pass, was so rough and rugged, Moore and Skookum Jim decided to head north over uncharted ground and seek an easier route to the Interior. They reached Lake Bennett, near the headwaters of the Yukon River, and named the new potential route, White Pass, for the Canadian Minister of the Interior, Sir Thomas White.

Moore had a 160-acre homestead claim in Skagway. He returned to his home and began to think about the changes he felt would soon come. The search for gold in northwest Canada and Alaska had been underway for the past two decades and Moore believed that it was only a question of time before gold would be discovered. He built a sawmill, a wharf and blazed the trail to the Summit of the White Pass. Moore even suggested to his son that eventually there would be a railroad through to the lakes, and to prepare for the coming gold rush.

The headline of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on July 17, 1897, broadcast the news of the discovery of gold in the Canadian Klondike. Under the headline "Gold! Gold! Gold!" the newspaper reported that "Sixty Eight Rich Men on the Steamer Portland" arrived in Seattle with "Stacks of Yellow Metal". The news spread like wildfire and the country, in the midst of a depression, went gold crazy. Tens of thousands of gold crazed men and women steamed up the Inside Passage waterway and arrived in Dyea and Skagway to begin the overland trek to the Klondike. Six hundred miles over treacherous and dangerous trails and waterways lay before them.

Some prospectors chose the shorter but steeper Chilkoot Trail, which began in Dyea. Each person was required to carry a ton of supplies up the "Golden Stairs" to the Summit of the Chilkoot Pass. Others chose the longer, less steep White Pass Trail, believing that pack animals could be used and would be easier. Both trails led to the interior lake country where stampeders could begin a 550 mile journey through the lake systems to the Yukon River and the gold fields. Both the Chilkoot Trail and the White Pass Trail were filled with hazards and harrowing experiences. Three thousand horses died on the White Pass Trail due to the tortures of the trail and the inexperience of the stampeders.

Men immediately began to think of easier ways to travel to the Klondike. In the fall of 1897, George Brackett, a former construction engineer on the Northern Pacific Railroad, built a twelve mile toll road up the canyon of the White Pass. The toll gates were ignored by travellers and Brackett's road was a failure. The 19th century was the era of railroad building and an easier mode of transportation into the north was of interest to everyone. Two men appeared on the scene with essentially the same idea: build a railroad through the White Pass. Sir Thomas Tancrede, representing investors in London, and Michael J. Heney, an experienced railroad contractor interested in finding new work for his talents, joined forces. Tancrede had doubts about building a railroad over the Coastal Mountains while Heney thought otherwise. "Give me enough dynamite and snoose" he bragged, "and I'll build a railroad to Hell".

They met by chance in Skagway, talked through the night and by dawn, the railroad project was no longer a dream but an accepted reality. It was a meeting of money, talent and vision. The White Pass & Yukon Railroad Company, organized in April 1898, paid Brackett $110,000; $60,000 and $50,000 in two separate payments for the right-of-way to his road. On May 28, 1898, construction began on the narrow gauge railroad.

On April 12, 1898, E.C. Hawkins of Denver Colorado arrived in Skagway to take charge of the work. By May 27 construction had begun with the laying of rails at Skagway and by mid-July the first locomotive in Alaska, 2-6-0 No. 2 purchased from a Utah shortline, arrived on the scene. In common with the mountain-piercing railroads of Colorado, the WP&Y would be built to a three-foot gauge to ease the problems of construction and reduce costs. As originally organized, the road would be operated as three separate entities: the Pacific & Arctic Railway & Navigation Company in Alaska (20.4 miles), the British Colombia Yukon Railway Company in British Columbia (32.2 miles) and the British Yukon Railway Company in the Yukon Territory. The latter segment was projected to Fort Selkirk but eventually terminated at Whitehorse, 58.1 miles from the territorial boundary.

At no time during the construction period were fewer than a thousand men employed, and the figure often reached 1,800 to 2,000. They worked in relays through the summer when daylight lasts virtually around the clock. Construction of the White Pass & Yukon began at sea level in the boom town of Skagway (then spelled "Skaguay"), during the spring of 1898. Here, on June 15th, work proceeds up the center of Broadway. Within just eight months the rails would reach White Pass Summit, 20.4 miles from Skagway at an elevation of 2,915 feet.

The obstacles facing the builders were almost unprecedented. When Hawkins arrived he found the mountain rising defiantly, buried in snowdrifts up to 30 feet deep and studded with sheer cliffs rising for hundreds of feet. There were no surveys completed, no rolling stock and precious little material with which to begin the work. He and contractor Michael J. Heney brought in an army of men from the States together with a commissary to feed them and $200,000 worth of supplies to equip the construction gangs. It was quickly found that the native timber was almost worthless because it splintered too easily. As a result, every tie, every bridge timber had to be imported. Ships were hurriedly chartered and soon were discharging all types of construction materials at the Skagway terminal, including quantities of dynamite – developed just 30 years earlier – was far more effective for this purpose that the black powder used by early railroad builders. Altogether, more than 450 tons of explosives were required to push the railroad to the top of this seemingly impregnable barrier.

For the first 20 miles out of Skagway the costs of constructions averaged $100,000 per mile, a staggering sum for that era. The first three miles along the Skagway River were relatively easy, costing just $10,000 each, but soon the difficult section near Rocky Point (milepost 7) was encountered, driving the cost per mile up to more than $125,000. At Porcupine Point a charge of 2,500 pounds of dynamite was detonated to blast off a huge slice of the mountainside, which fell with a deafening roar into the Skagway River below, changing its course. At Tunnel Mountain (milepost 15) workers were forced to lower themselves over a cliff on stout ropes, where there was scarcely footing for an eagle, in order to drill holes in the sheer rock and set explosive charges. A 250 foot tunnel had to be drilled here on the north side of a chasm, as the railroad ascended a grade of 3.9 percent. South of the tunnel Heney’s men stood on a narrow shelf which would soon support the railroad and gazed downward to the river more than a thousand feet below. Behind them, a mile downgrade, they could see the big loop above Bridal Veil Falls, where an encampment known as "White Pass City" had sprung up near the railroad. At least 35 workers were killed in construction accidents before the line was completed.

On Jul 21, 1898 the WP&Y operated its first train from Skagway to a point four miles north of town. On August 15, an inspection train puffed all the way to Porcupine Point where the locomotive drew up to the very last rail laid. The party of investors, company officials and guests rode a flatcar roped in on the sides, detraining at the end of track to peer cautiously over the edge of a stone wall atop the precipice. Skagway, which in a year’s time had boomed from a sleepy village into a raucous city of 20,000, could clearly be see in the distance. By August 25 trains were operating as far as Heney station (12.7 miles), at the confluence of the Skagway River and its White Pass Fork, as the rails continued to advance rapidly up the face of the mountain.

Employing a switchback near milepost 19, the main track was completed to the summit on February 18, 1899, in the dead of a harsh Alaska winter. The first passenger train to complete the 20.4-mile trip struggled to the top on February 20, its passengers undoubtedly awed by the spectacular view down the canyon to Skagway and salt water just 14 miles away.(Two years later an immense steel cantilever bridge was built across Dead Horse Gulch, soaring 215 feet above the White Horse Fork, which eliminated the cumbersome switchback. According to legend, however, the first ticket on the new railroad had been issued some months earlier, in August 1898. A man going on to Dawson pleaded to be taken on board one of the inspection trains to the end of track. He paid 25 cents a mile and upon receipt his receipt was endorsed by an official as the first ticket sold by the WP&Y and the first to be issued in Alaska.

Rolling stock was purchased and delivered to Skagway as the need arose. By the end of 1899, the road rostered 13 locomotives, eight passenger coaches and 250 freight cards. A shop was constructed two miles north of town and several stations were erected, including a substantial depot at Skagway. On July 6, 1899, the first train reached Lake Bennett in British Columbia, at milepost 41, amid the rejoicing of miners and prospectors who until that time had toiled for days to pack their outfits to a point now reached by rail in three hours. While snow was an implacable enemy of the construction gangs, the building of snowshoes and the use of a rotary snow plow made it possible to continue service except during the times that blizzards were raging. Snowdrifts were present much of the year but the fact that the railroad for the most part was built high in the rocks made it nearly immune from spring washouts.

The White Pass & Yukon Route climbs from sea level in Skagway to almost 3,000 feet at the Summit in just 20 miles and features steep grades of almost 3.9 percent. The tight curves of the White Pass called for a narrow gauge railroad. The rails were three feet apart on a 10-foot-wide road bed and meant lower construction costs. Building the one hundred and ten miles of track was a challenge in every way. Construction required cliff hanging turns of 16 degrees, building two tunnels and numerous bridges and trestles. Work on the tunnel at Mile 16 took place in the dead of winter with heavy snow and temperatures as low as 60 below slowed the work. The workers reached the Summit of White Pass on February 20, 1899, and by July 6, 1899, construction reached Lake Bennett and the beginning of the river and lakes route.

While construction crews battled their way north laying rail, another crew came from the north heading south and together they met in Carcross on July 29, 1900, where a ceremonial golden spike was driven by Samuel H. Graves, the president of the railroad. Thirty-five thousand men worked on the construction of the railroad - some for a day, others for a longer period, but all shared in the dream and the hardship. The $10 million project was the product of British financing, American engineering and Canadian contracting. Tens of thousands of men and 450 tons of explosives overcame harsh and challenging climate and geography to create this wonder of steel and timber.

For decades, the WP&YR carried significant amounts of ore and concentrates to Skagway to be loaded upon ore ships. During World War II, the railroad was the chief supplier for the US Army's Alaska Highway construction project. The railroad was operated by steam until 1954, when the transition came to diesel-electric motive power. White Pass matured into a fully-integrated transportation company operating docks, trains, stage coaches, sleighs, buses, paddle wheelers, trucks, ships, airplanes, hotels and pipelines.

World metal prices plummeted in 1982, mines closed and the WP&YR suspended operations. Six years later, WP&YR reinvented itself as a tourist attraction. The line reopened in 1988 to operate as a narrow gauge excursion railroad between Skagway and White Pass Summit.

My White Pass and Yukon Railroad Trip

Right at 8:00 AM, we pulled away from the station to start our narrow gauge train trip to Lake Bennett.

We turned north at Skagway Junction where a line goes down to the dock; this is where the Sun Princess was.

We then passed the railroad shops, with RSD-35 114, built by Bombardier in 1982, followed by the Gold Rush Cemetery.

Our train proceeded out of Skagway following the Skagway River.

A few miles later we turned east to parallel the east fork of the Skagway River which we crossed at Denver.

Starting to ascend the grade after reversing direction to the west as we made our way to Rocky Point.

The views from Rocky Point.

We were now high above the Skagway River with the highway on the opposite canyon wall.

The train rode high above the gorge then at MP 9, we train crossed a bridge over Pitchfork Falls and next was a monument called Black Cross Rock in honour of the town's railroad builders who were buried under a 100 ton granite rock on August 3, 1898.

Our train passed Buchanan Rock across the canyon with "On to Alaska with Buchanan" painted on it. George E. Buchanan, a Detroit coal merchant, began bringing boys and girls to Alaska on adventure trips in 1923. His goal was to help young people learn the art of earning and saving money. To accompany Buchanan on these special excursions, a young person had to earn one third of the cost of the journey. The parents could pay one third and Buchanan contributed one third. If necessary, he assisted the would-be adventurer to earn his share of the costs.

For fifteen years, groups of approximately 50 young people, mostly boys, made the annual summer excursion from Detroit to Alaska. The travellers departed from Detroit in mid-July, travelling first class by train across Canada to Vancouver British Columbia and Puget Sound. Three days on a steamer and then arrival in Skagway. They boarded the White Pass & Yukon Railroad to travel to the lake country and then a transfer by boat to Atlin. The young folks, dressed in coat and tie, had to be on their best behaviour. Many years later, members of the various Buchanan Boys groups returned to Skagway to ride the WP&YR and to revisit the memories of their special and happy trips. Reportedly, the boys from one of the summer trips painted the sign "On To Alaska With Buchanan" on the side of the mountain to commemorate their inspiring leader, George Buchanan.

Further up the canyon Bridal Veil Falls could be seen off to the west and our route then took us to Henry.

The tracks turned east and high above the canyon was our future route.

Passed the siding at Glacier.

Another horseshoe curve took the train over the Skagway River.

We continued to climb, now to the west, on a ledge over many trestles. It was absolutely spectacular.

Down below, where we had been minutes ago, the train to Fraser was following us.

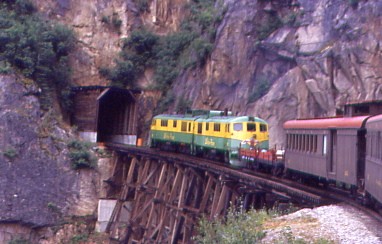

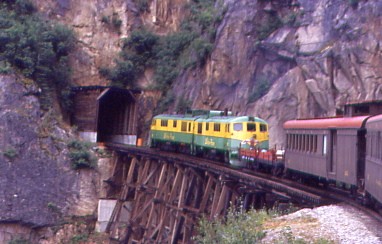

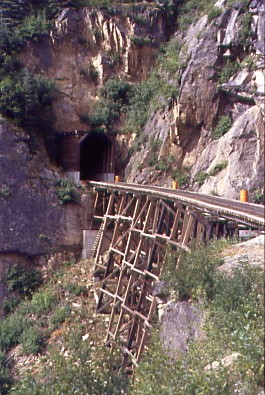

We crossed the high trestle before plunging into the 300 foot tunnel through Tunnel Mountain with us now 1,000 feet above the gulch.

From Inspiration Point, you could see all the way down to Lynn Canal as we continued to climb.

The train turned north high above Dead Horse Gulch.

Maintaining our ascent, we entered the clouds then in fog, passed the Steel Bridge constructed in 1901, which was the tallest cantilever bridge in the world at that time and was used up to 1964. It was impossible for me to get a picture of this bridge going north.

We crossed the New Bridge and entered the 675 foot tunnel built in 1969 at MP 18.8. Exiting the tunnel across the stream was the Old Trail of '98.

A mile later, we traversed White Pass Summit at 2,865 feet, the Continental Divide and the United States of America/Canada border as we entered British Columbia.

Our train followed Summit Lake across the rocky terrain as we were above the tree line.

Descending, twisting and turning.

At Gateway was an old section house.

Lakes and rocks continued along our route.

We reached the highest point on our route at Meadows at 2,924 feet.

From there, the train descended two hundred feet as the trees returned before we reached Fraser and Canadian Customs.

The Customs office is on the highway and would have to close to inspect the train. Our conductor received a count of everyone's nationalities and that would suffice for the customs officer.

We had to pull forward to let the Fraser train enter the station, where their locomotives had to cut in order to run around to return to Skagway.

Fraser Lake was a beautiful sight.

Our pair of diesels really smoked it up as we departed.

We followed the shore of Fraser Lake curving along the water's edge.

We next rolled along Portage Lake.

Crossing the North Klondike Highway where people were taking pictures of our train.

This bought our train to Log Cabin where there were track inspection speeders. We then crossed a beautiful meadow, albeit with no animals, and went by Bear Lake.

Curving down the grade high above Lake Linderman (as it was known in 1890) or Lake Lindeman, as it is known today.

The view before we descended to Lake Bennett.

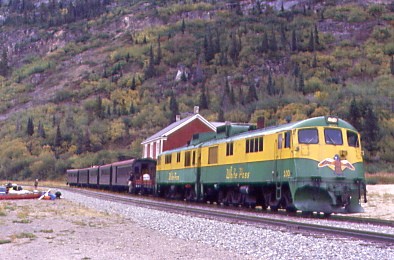

The train travelled around the balloon track here then reversed in front of the Lake Bennett station. The conductor opened the lunch room and meals were distributed from the last car of the train. I wrote most of this journey's details as I snacked.

Our train at Lake Bennett.

Lake Bennett from the west.

White Pass and Yukon 85 ton 100 built by General Electric in 1966, and 85 ton 92, built by General Electric in 1956. We had a two-hour layover before our passengers returned for the trip back to Skagway.

One last view of our train here.

The coaches have large windows, with smaller ones at one end of the car, the restroom is at the other end of the car. Free tea and coffee are set up and a stove warms the car and in addition, outside platforms are located at both ends.

At 12:53 PM, the train started its return journey.

We returned to Fraser with no US Customs to deal with before we took the siding.

Our train at Fraser.

White Pass and Yukon railbus 5 "The Red Line" built by Beartown in 1998, photographed while waiting for the afternoon Fraser train to arrive.

A work train on the Fraser balloon track.

The United States/Canada border.

Starting the long grade back to Skagway at sea level.

Dead Horse Gulch.

The cantilever bridge.

Down the grade we go!

Great views as we descended.

The view all the way back down to the water.

Descending nicely.

Where we would be in a few minutes.

Curving off the great wooden trestle.

Running along the cliff.

A look back at the fantastic wooden trestle.

The Skagway River crossing at Glacier.

A look back to where we were a few minutes ago.

The last crossing of the Skagway River.

The Gold Rush Cemetery.

White Pass and Yukon 2-8-2 73, built by Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1947. It was retired in 1963 and displayed at Bennett from October 1968 to 1979 then used in excursion service until 1982 and returned to the rails in 1988.

We arrived at Skagway twenty-five minutes early and before detraining, an American customs agent walked through the train to quickly check our passports. That ended a fantastic excursion on the White Pass and Yukon Railroad. A special thank you to Michael Brandt of Ticketing, Phil Bruehler, our onboard guide, Jeff Ruff, our engineer, David Dobbs, our conductor and Elizabeth Ruff, Jeff's daughter, as our brakeman. Without all of their help, my experience would not have been such a success.

Our train at rest.

I walked to the post office before returning to the Sun Princess, stopping at Dewey Creek to watch the salmon attempting to climb a little waterfall. Back on the ship, I watched the end of "Starsky and Hutch" and after a walk, the end of "Haunted Mansion".

When I was up on deck between the films, I spotted a pair of orcas in the channel to the west. For one male passenger, this was the first time he had ever seen a whale. I went for another walk before changing for dinner and had my usual steak. One of the features about dining each night with these same great people is hearing how each of them spent their day on and off the ship. We departed while we were eating and after dinner, I went for an evening walk on the Lido Deck and had to be really careful not to be blown off. Sports Center was watched before I called it a night.

The Sun Princess left Skagway by sailing south down Lynn Channel to where we met the Icy Strait and turned northwest up towards Glacier Bay.

| RETURN TO THE MAIN PAGE |