This long web page is taken from a series of articles which was published in The Double 'A' in the Fall of 1997 and Winter of 1998 and combined into one story. This will give a construction era view of the building of the railroad along with the change through reorgizaton into the Ann Arbor Railroad Company as it was known, up until about 1906 in time-frame.

BACKWARD IN TIME BUILDlNG - THE ANN ARBOR RAILROAD

By Graydon Meints

Note: This paper is a preliminary study of one aspect of the Ann Arbor Railroad. It attempts to outline the development of the Ann Arbor system, and the changes in its corporate structure and physical plant up to approximately 1900. It does not consider much of its financial history, operations, or its equipment. This study should be taken as a work in progress, rather than as a complete and definitive history. The conclusions expressed are those of the writer, drawn from the best evidence available. The mileages used throughout are those as developed by the writer.

It is the hope of both the writer (Graydon Meints) and the editor (Rob Adams) that this paper will stimulate new interest in the Ann Arbor's past and encourage others to undertake further study.

The oldest part of the Ann Arbor Railroad was built and originally owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad. In 1871, the Pennsylvania had stepped in to help a company named the Mansfield, Coldwater & Lake Michigan. Long on ambition, the company was equally short of funds. With cash provided by the Pennsylvania, the company finally was able to begin construction and built from both ends of its proposed line: from Allegan, eastward, and from Toledo Junction, near Mansfield, Ohio, northwesterly. On May 1, 1873, the eastern most 37 miles were completed as far as Tiffin, Ohio. On that same day another Pennsylvania-supported line, the Toledo, Tiffin & Eastern, completed 24 miles of road between Tiffin and Woodville, Ohio. The City of Toledo owned the Woodville line, which had been built for it by the Pennsylvania under an 1872 agreement. Part of the understanding with the city was that when the line was completed, it was to be leased to the Toledo, Tiffin & Eastern. [1]

As part of getting into Toledo, the Pennsylvania became involved with another little line, the Toledo & State Line (see Appendix 1). The State Line was incorporated on June 30, 1872, and it proposed to build a 5 mile line from Toledo north to the Michigan state line.[2] On September 9, 1872, the State Line's owners contracted with the Pennsylvania to have it build the road. It took nearly two years to complete, and the line was opened for business officially on August 5,1874. The 5.1 mile line extended from the site of the Pennsylvania's Summit Street station in Toledo to Alexis.[3]

At Alexis, the road connected with the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern's Toledo-Detroit branch, and also with the Toledo-Detroit line of the Canada Southern. At its completion, the State Line was leased to the Pennsylvania for 999 years, in return for a guarantee of the interest on the road's bonds.[4]

Why the Pennsylvania acquired the State Line can only be speculated about. It did not need the property as an entry into downtown Toledo, or to gain access to the Maumee River; as it had these with the Woodville line. It may have planned it as a link to the Toledo & Northern, which was projected to build to Monroe, or to the Toledo, Ann Arbor & Northern, which, as will be seen below, planned to build to Shiawassee County in Michigan. It may have been intended to provide a connection for the Canada Southern's line to reach downtown Toledo. Or, it may have planned to use the road as a jumping off point for its own extension into Michigan, to gain access to forested empire that was swelling the profits of other companies.

As early as 1845, the citizens of Ann Arbor were talking about the need for a railroad that would operate between Ann Arbor and Toledo.s The Michigan Central had been built from Detroit into Ann Arbor in 1839, and the feeling was that it had such a monopoly on traffic that it could charge freight rates as high as it wished. A competing rail line would force the MC to lower its charges. Nothing came of this talk until the end of the Civil War. Building railroads then became the rage and new projects sprang up everywhere in Michigan.

A group of Ann Arbor, Howell and Dundee businessmen incorporated the Toledo, Ann Arbor & Northern Railroad on October 22, 1869. The proposed line was to be 100 miles long, extending from the Ohio state line near Toledo, via Ann Arbor, to Owosso.6 The City of Ann Arbor voted $100,000 in bonds to aid the company and Ann Arbor Township added another $10,000.[7] By the end of 1873, the company had acquired a right of way and graded about 38 miles of road south of Ann Arbor.[8] Just as things were looking favorably for the company, the Panic of 1873 developed. Money began to dry up and railroad projects everywhere stopped; work also halted on the TAA&N. On August 13, 1875, the company was declared bankrupt.[9] On September 28, all of the road's assets were sold to Benjamin P. Crane, one of the contractors building the line. The company had spent a total of $154,078.16 up to the date of sale; Crane bought it all for $1,001.[10]

On June 9, 1877, Crane sold his purchase to James M. Ashley for $25,000.[11] Ashley, had previously been a congressman from Toledo, and then, for a year, served as the territorial governor of Montana. He had returned to Toledo only shortly before he bought from Crane. The governor is reported to have said, "I got out of a job in politics, came back to Toledo, and, having no business to get back into and very little money, I decided to build a railroad."[12] Working with him were his equally ambitious sons, James Jr. and Henry W., nicknamed "Harry".

During the summer of 1877, Ashley went to Ann Arbor to try to raise funds to build his railroad. A strike in July that had threatened to close down the Michigan Central was fortuitous. Ashley, apparently, was able to raise enough money to begin construction. On November 23,1877, he filed incorporation papers for the Toledo & Ann Arbor Railroad to use the franchise of the TAA&N.[13] On January 29, 1878, Ashley signed a personal contract with his railroad to build its line.[14] Track laying was completed between Alexis, Ohio and Ann Arbor by May 16.[15] On May 1, 1878, Ashley's company bought the Toledo & State Line from the Pennsylvania Railroad. The consolidation papers were dated May 11, 1878, and were filed in Michigan on May 24 and in Ohio on May 28.[16] How much Ashley actually paid for the State Line is unclear.

On June 21,1878, the first freight train operated into Ann Arbor. Regularly scheduled passenger train service began a few days later, kicked off by the customary special trains carrying dignitaries who made the customary speeches at the customary dinners and also celebrated the customary number of alcoholic toasts. The line was 45.8 miles long and extended from the Summit Street station in Toledo to a station in Ann Arbor on the south side of Miller Street at MP (Mile Post) 45.6. The company owned 5.9 miles of road in Ohio and the remaining 39.9 miles in Michigan.

Ashley's next step was to form a second, new company that could extend his line north from Ann Arbor. The incorporation papers of the Toledo, Ann Arbor & North Eastern were dated September 9, 1878, not long after the line into Ann Arbor had been completed. The new company proposed to build 33 miles of line from Ann Arbor to Pontiac. [18] Construction on the line began in October of 1879, with Ashley as the contractor. [19]

Ashley's rails had come to Ann Arbor nearly forty years after those of the Michigan Central; new traffic must have been hard to find. An extension was a logical attempt to develop needed new traffic. Only a dozen miles north of Ann Arbor, was the line of the Detroit, Lansing & Northern which extended from Detroit, through Lansing and Ionia, to Howard City, where it connected with the Grand Rapids & Indiana to northern Michigan. The DL&N also was then building a new line from Ionia north to Big Rapids.[20] A little farther on, at Wixom, was the Flint & Pere Marquette line which extended to Saginaw, and northwesterly into lumber country. At Pontiac, the line could connect with the western end of the projected Michigan Air Line Railway, which was controlled by the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada. Also at Pontiac, was the DetroitGrand Haven line of the Detroit, Grand Haven & Milwaukee. Of these four lines, only the F&PM had access to Toledo, and that was by using the tracks of the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern, between Monroe and Toledo. Ashley might have figured that his new company could get the Toledo-bound traffic from the D&LN and the MAL at the least, and possibly some from the others.

After construction was underway, Ashley consolidated the Ann Arbor and the North Eastern into a new company, the Toledo, Ann Arbor & Grand Trunk. The consolidation was effective October 14, 1880, and the new line carried over, unchanged, the rights of its two predecessors: a line from Toledo to Pontiac.[21] The line was opened to regular service from Ann Arbor as far as South Lyon, in August, 1881.[22] It is possible that the track was in place as early as May. [23] The length of the new construction, from Ann Arbor to South Lyon, was 14.2 miles.

When Ashley's rails got to South Lyon, the situation had changed. In September of 1879, the Grand Trunk of Canada obtained control of most of the parts needed for its own route between Port Huron and Chicago.[24] Its Michigan Air Line into Pontiac was no longer needed as a part of its plan to gain a route to Chicago. Despite this change, Ashley already had said he planned to finish his line to Pontiac by September 1, 1881.[25]

Ashley formed another railroad, the Toledo & Saginaw Bay Railway, on August 15, 1881, which would build a 120 mile line from Pontiac to Caseville.[26] At Pontiac, he also would be able to connect with the proposed Pontiac, Oxford & Port Austin, which also planned a line north from Pontiac into the Thumb region. In September, a massive forest fire swept over the Thumb. Gone in a day, was the lumber that could bring profits, and with it vanished the appeal of building to the Thumb. To make the best of a bad situation, Ashley appears to have struck a deal with the Grand Trunk.

On January 21, 1882, and filed for record on March 29, the Michigan Air Line amended its franchise, and proposed to build from Pontiac to Jackson.[27] On October 25, 1882, the MAL bought the grade and franchise between South Lyon and Pontiac from Ashley for $45,000.[28] The MAL moved quickly, and had its line between Pontiac and South Lyon in operation in October of 1883.[29] The outcome was somewhat different than Ashley had originally planned, but his goal was realized in most part. At South Lyon, he had connections with both the Detroit, Lansing & Northern and the Michigan Air Line. He appears to have discarded the Toledo & Saginaw Bay project, although the Pontiac, Oxford & Port Austin did decide in late 1881 to build to Caseville rather than to Port Austin.[30]

Ashley apparently held on to the hope of providing a Toledo outlet for the Grand Trunk system. On August 12, 1882, he amended the incorporation papers of the TAA> to authorize him to operate a line from Toledo, via South Lyon, to Durand.[31] With this changed route, he could connect with the Grand Trunk's Chicago Port Huron main line as well as with the Detroit, Grand Haven & Milwaukee, since the two crossed at Durand.

The next part of the Ann Arbor's system came into existence before Ashley was involved with it. A group of Owosso men organized the Owosso & Big Rapids Railroad on June 26, 1869. They planned to build an 81 mile line between the namesake towns. On December 22, 1871, the company, headed by Thomas D. Dewey of Owosso, modified its name to the Owosso & North Western, and changed its western destination; rather than to Big Rapids, it now planned to build 150 miles from Owosso to Frankfort via Alma.[32]

The company never raised much money, and had been able only to buy a right of way and grade some line between Owosso and St. Louis[33] Ashley saw a possibility in the unused grade. On October 28, 1882, he incorporated the Toledo, Ann Arbor & North Michigan - the first of a number of companies to bear that name. The North Michigan proposed to operate a line from St. Louis, via Alma, Ithaca, and Owosso, to the TAA> line near South Lyon.[34] In other words, the North Michigan would be an extension of Ashley's existing road.

Ashley bought the Owosso's grade in 1883 for $180,000 in North Michigan 6% first mortgage bonds and $180,000 in North Michigan stock, although the stock may have been a bonus to encourage the buyers to take the bonds. On September 29, 1883, Ashley signed a contract with his North Michigan to build the line from Owosso to St. Louis.[35] By early 1884, Ashley decided that he wanted his railroad to be built from Owosso directly to St. Louis, rather than by way of Alma as the incorporation papers called for. [36] From St. Louis, Ashley thought he might build through Mt. Pleasant and Lake City on his way to Frankfort.[37] Rails were laid from Owosso as far as Ithaca on June 3, 1884, and to St. Louis by June 27.[38] The line was put in regular operation in early August.[39] By this time, Ashley also had run surveys as far as Mt. Pleasant to extend his line north.[40] Also, he had received pledges of financial assistance to extend his railroad to Mt. Pleasant.[41]

The Owosso - St. Louis segment began at a connection with the Detroit, Grand Haven & Milwaukee (now Grand Trunk Western) line just west of Owosso Junction. It followed the present Ann Arbor line as far as MP 137.0 east of Ithaca. At that point, it continued northwest rather than curving to the west. It crossed Union Road at the north village limits, crossed State Road about 1/4-mile south of Polk Road, then continued north about 112-mile west of and parallel to State Road. In St. Louis, it crossed Darragh Street just west of Fairbanks and continued north to and then along the Pine River, ending about one block north of the intersection of Watson and North Streets in St. Louis. The line was 39.0 miles long.

The purchase of the O&NW is the first mention of a terminus on Lake Michigan. It is uncertain when Ashley first developed the idea of building to the lake shore. Some writers have stated that Ashley had this intention from his initial involvement with the Ann Arbor.[42] Until the amendment of the articles of the TAA> and the formation of the North Michigan in August and October 1882, Ashley's intention appears to have been to build northeast from Ann Arbor, not north or northwest. It seems much more likely that he formed his plans as opportunity presented. It was not until 1888, with the formation of the Toledo, Ann Arbor & Lake Michigan, that Ashley formally named any Lake Michigan town as his road's terminus. That the O&NW's western goal should be Frankfort probably is not much more than a general indication of hopeful intentions. It does seem reasonable, however, to conclude that Ashley had decided on a Lake Michigan goal by 1884. The 1883 annual report of the TAA> carried a map showing a line projected to Frankfort.[43] Opportunist and innovator that he was, Ashley probably had seen the lake transfer service of the Pere Marquette at Ludington. But neither the Pere Marquette, which had reached Ludington in 1874, nor the Grand Trunk, which had been built into Grand Haven in 1858, had advanced beyond the break-bulk method of cross-lake shipping. They were content to unload freight from rail cars at one port, transfer it to the ship, then reload it into rail cars at the opposite port. Also, he was familiar with the car ferry services across the Detroit and St. Clair Rivers. Just when the flash of inspiration occurred, to ferry loaded freight cars across Lake Michigan by ship, is unknown. The Mackinac Transportation Company ordered its first railcar ferry in 1887 for service at the Straits of Mackinac.[44] This open-water route may have been the inspiration. It was not until 1890 that Ashley first asked for plans for a trans-lake railcar ferry.

Ashley now had to bridge the gap between the ends of his two lines at South Lyon and Owosso. On May 19, 1884, he consolidated the North Michigan and his Grand Trunk into a new North Michigan. The articles provided for a line between Toledo and St. Louis and included the rights of the two merged partS.[45] Construction to close the gap mostly likely began in 1884.

In 1885, Ashley completed the line between Durand and Hamburg, the distance given as 33.1 miles.[46] This statement is misleading for several reasons. First, as part of the connecting link, Ashley obtained trackage rights over the Michigan Air Line between South Lyon and Hamburg Junction, as Lakeland was then known. Second, the south end of construction was at about MP 62.2, about one-half mile west of the MAL crossing at Lakeland. The north end of the project was at the road's Durand station, which at that time was located at the site of the Ann Arbor Railroad freight house at MP 95.7. According to the Michigan Manual of 1890, the distance between these two points is 34.8 miles. South of Oak Grove, the distances between stations agree closely with those of the route in use now. It appears that between Durand and Oak Grove the line was on a substantially different route. At about MP 82.7, the original line diverged slightly to the east of the present route, crossed it a short distance south of Byron, and proceeded northwest and then north into Durand. In Durand, it connected with the original route where it crossed the Detroit-Grand Haven line of the Grand Trunk Western at MP 95.2. The distance between MP 82.7 and 95.2, via the old route, was 1.3 miles longer than the present route. This is confirmed by the Ann Arbor's chief engineer who states the line was substantially relocated in later years.[47] Third, he mentions in another place that the line between Howell and Chilson was relocated.[48] It appears that this was not an extensive relocation, since the original mileages differ only minimally from present mileages. Very likely, the grade was moved east out of the marshes that parallel much of the present line, to slightly higher ground. The result was that the construction, together with trackage rights between South Lyon and Hamburg Junction (Lakeland) and between Durand and Owosso Junction, Ashley had his line tied together and was able to operate trains between Toledo and St. Louis.

In October of 1886, Ashley finished building his own line between Durand (MP 95.7) and just west of Owosso Junction (MP 107.9), a distance of 12.2 miles.[49] Also in 1886 he built a section from Leland, at MP 52.2 on the South Lyon line, to a connection with the MAL at a point 0.4 miles east of Hamburg on that line. This segment was 8.9 miles in length. Ashley kept trackage rights over the MAL between the two ends of his tracks, at the Hamburg connection and Hamburg Junction (Lakeland), effective June 21, 1886.[50] With the round-about route through South Lyon eliminated, Ashley had achieved a reasonably direct route between Toledo and St. Louis.

Ashley also was busy in 1886, planning how to extend his road north from St. Louis. At first, he had considered building directly north from St. Louis, then angling northwest to reach Mt. Pleasant[51] This route would bypass Alma completely and Ashley failed to consider the wishes of Alma's leading citizen, Ammi W. Wright. Wright was a very wealthy lumberman from Saginaw. He had built the St. Louis & Saginaw Valley Railroad from Saginaw to St. Louis in 1872.[52] Wright had substantial business interests in Alma, and made it his home. Wright favored having a railroad that ran north from Alma, not from St. Louis, and Wright had considerably more money than Ashley.

Wright had been one of the promoters of the Saginaw & Grand Rapids which built a line from St. Louis to Alma in 1879, and also of the Ithaca & Alma, which had been built in 1882.[53] More importantly, at that time Wright was one of a group promoting the idea of a railroad from Lansing, through Alma, north to some place to be decided as opportunity presented. This road had been talked since the end of the Civil War, but there had been more rhetorical than financial support coming from the businessmen of Lansing. Wright had money enough to build the line on his own, but he did not do so.

Below: A turn-of-the-century view of Lakeland, showing the hotel, interlocking tower, and, in the distance, the first depot at the location. The Ann Arbor track in the foreground crosses the Grand Trunk and then continues behind the depot. Zukey Lake is out of view to the left. - C. T. Stoner Collection, photo AA70

As Ashley pushed his rails into St. Louis, Wright decided to act. On February 5,1884, Wright incorporated the Lansing, Alma, Mt. Pleasant & Northern Railroad. It was to build a 68 mile line from Lansing to Mt. Pleasant.[54] The long and tortuous career of this road is discussed at length in Ford Stevens Ceasar's The Lamp Road. In any event, Wright began building north from Alma and completed about twelve miles of railroad during 1885.[55]

By December, 1885, Wright and Ashley apparently had struck a deal. [56] Ashley agreed to buy the LAMP from Wright and its owners, and also would build a connection between St. Louis and Alma that would connect the LAMP to his own line. With this move, Ashley would acquire a partly built line and its financing, and at the same time remove a possible competitor. Wright, for his part, would get his wished-for line extending north from Alma and the freight traffic into Alma that it would provide. It appears that Ashley made no attempt to use any of the LAMP franchise rights south of Alma.

In March, 1886, Ashley bought the LAMP. He paid $122,530.11 for the company's stock and bonds. For this price, he acquired $142,000 of common stock that Wright and his friends owned, and $143,000 of 6% first mortgage bonds authorized, although possibly not all of the bonds had been issued. [57] On May 5, 1886, Ashley gave the LAMP a new name: the Toledo, Ann Arbor & Mt. Pleasant Railway.[58] Its line into Mt. Pleasant was completed on July 1, 1886.[59] As built, the line extended from Mt. Pleasant to the Pine River at the south end of Lincoln Street in Alma, and was 18.6 miles in length.

The St. Louis-Alma connection, that Ashley had to build to hook the Mt. Pleasant line to the rest of his system, has its own involved history. In August, 1875, the Chicago, Saginaw & Canada built a line from St. Louis west to Cedar Lake, and a few years later extended farther west. This line was built due west from the present CSX station in St. Louis, crossed the Pine River, swung southwest along the north side of the river, passed east-west through Alma very near Washington and Elwell Streets, then continued due west toward Edmore. In 1879, another company, the Saginaw & Grand Rapids, built the present line between St. Louis and Alma that is south of the Pine River. The S&GR was controlled by the Saginaw Valley & St. Louis, and both companies came under the control of the Detroit, Lansing & Northern in 1879. The Chicago, Saginaw & Canada was reorganized in 1883 as the Saginaw & Western; the S&W was formed by the owners of the Detroit, Lansing & Northern which leased the S&W at incorporation.[60]

The DL&N built a connection in Alma between the west end of the S&GR line and the S&W line northwest of town. The DL&N then removed the S&W rails from St. Louis to the new connection in Alma. On March 17, 1887, the DL&N sold the abandoned right of way to Ashley.[61] He built a short connection "wye" to the LAMP in Alma, north Elwell and west of Wright Streets. The St. Louis leg of the connection was a bit more complicated. It appears that Ashley built from just north of Graham and Fairbanks Streets in St. Louis, where he connected with the line into St. Louis from the south, to somewhere in the vicinity of Surrey Road, at which point he made a sharp curve to the west and came onto the old grade of the CS&C. The total length of the connection built was 4.2 miles.[62] The Alma station was located just east of Wright Street, north of Elwell Street.

In 1886, the North Michigan also built a 1.6 mile branch from Macon, apparently at MP 24.9, to the Macon Quarry.[63] Table 1 summarizes the mileage to this time.

|

Table 1 |

Total miles |

|

Toledo (Summit St.) - Michigan state line |

5.9 |

|

Ohio state line - Leland |

46.5 |

|

Leland - South Lyon |

7.6 |

|

Leland - GT connection at Hamburg |

8.9 |

|

GT connection at Lakeland - Durand (old station) |

34.8 |

|

Durand (old) - Owosso Jet. |

12.2 |

|

Owosso Jct. - St. Louis |

39.0 |

|

Connection at St. Louis - Connection at Alma |

4.2 |

|

Alma (Pine River) - Mt. Pleasant |

18.6 |

|

Macon - Quarry |

1.6 |

| Total miles | 179.3 |

As Governor Ashley was laying rails into Mt. Pleasant in the early months of 1886, he also was planning for the extension of his company to the north. On June 17, 1886, he incorporated the Toledo, Ann Arbor & Cadillac Railway. Its purpose was to build a 63 mile line between Mt. Pleasant and Cadillac.[64] Earlier in the year, on January 20, Ashley had incorporated the Toledo & Cadillac Railroad. What use he made of this company is unclear, although it is possible he used it to buy right of way. No construction was done by it and there was no record of transfer of its rights to the June company.

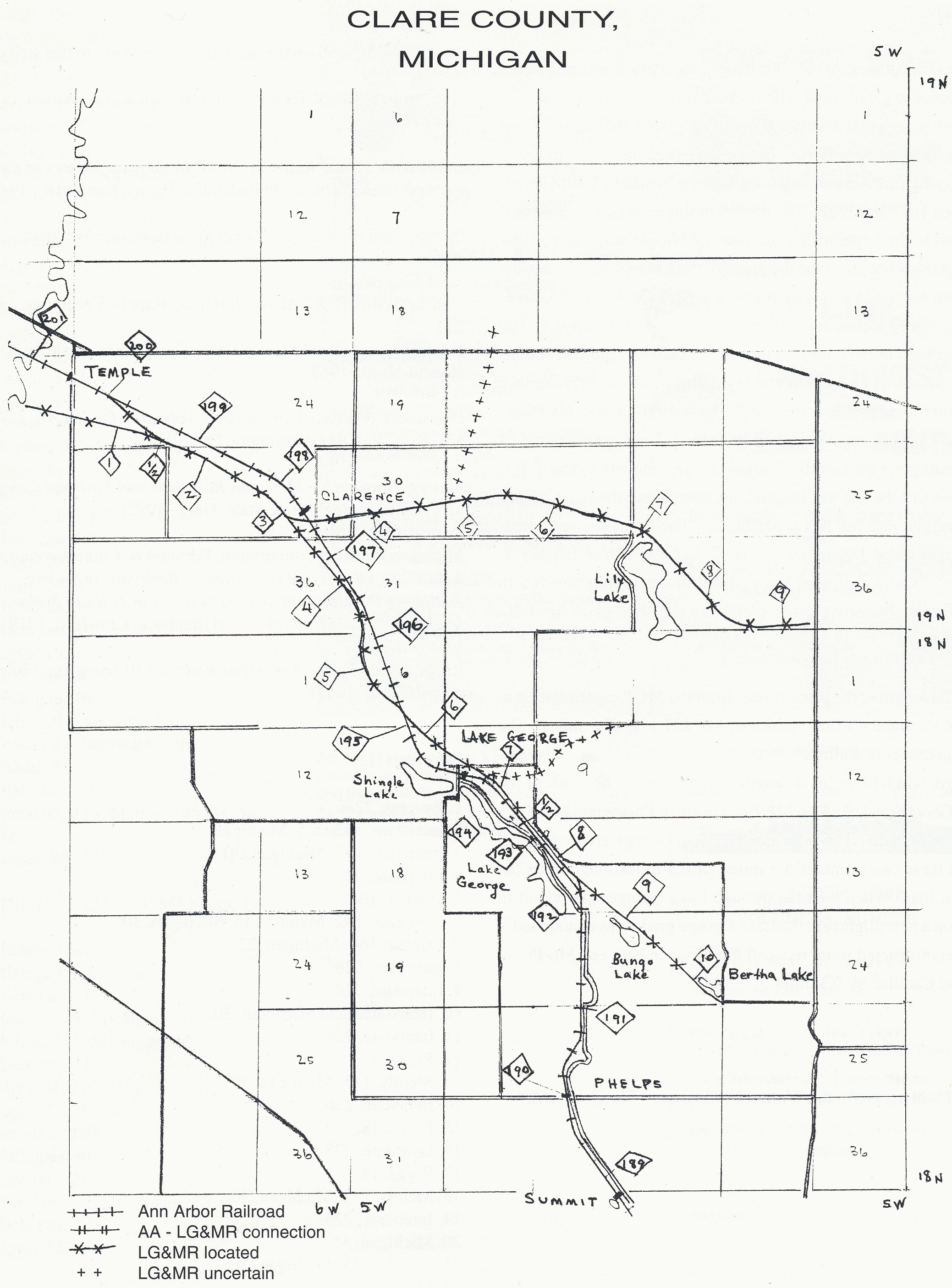

In other places, Ashley had bought the unused grades of other companies to get his own railroad built more quickly. In this section, he discovered another abandoned grade; that of the Lake George & Muskegon River. The Lake George line was a pioneering logging railroad and had been built by Winfield Scott Gerrish between 1877 and 1880. The history of this company is discussed in detail in the September 1960 issue of Michigan History magazine. Ashley bought some the grade of the Lake George sometime between August 25 and December 20,1886.[66] On August 24,1886, Ashley signed a contract with the Cadillac to build its line.[67] The road appears to have been built very quickly and quite economically. In later years, substantial regrading was required to reduce the short rolling profile of the line.[68] The section between Mt. Pleasant and Cadillac was completed in 1888.[69] The Commissioner of Railroads gives the month of August as the completion date.[70] It is possible, that the line was substantially completed when the Cadillac was merged into the North Michigan. The consolidation agreement was dated December 21, 1887, to be effective January 1, 1888.[71] The articles of consolidation amending the North Michigan's charter were not filed with the state until April 20, 1888.[72]

The length of the present line, from the Mt. Pleasant station at MP 163.8 to the Cadillac station at MP 227.1, is 63.3 miles. The Commissioner of Railroads states that the route, as originally constructed, was 63.6 miles in length.[73] Ashley used the grade of the Lake George road between MP 192.1 north of Phelps and MP 200.3 south of Temple. The length of the Lake George grade used between these two points is 8.5 miles, or 0.3 miles longer than the current line. When the road through Lake George was rebuilt in 1894 on a new alignment the Lake George grade was abandoned.[74] The reconstructed route reduced the distance between Mt. Pleasant and Cadillac by 0.3 miles.

Ashley next turned to completing his railroad to Lake Michigan. On March 5,1888, he formed the Toledo, Ann Arbor & Lake Michigan Railway to build a 60 mile line from Cadillac to Frankfort.[75] He signed a construction contract on June 8 to build the line.[76] Tracklaying must have started immediately since the line was finished as far as Harrietta by the end of 1888.[77]

Frankfort was not the only Lake Michigan port available to Ashley. The Pere Marquette line from Saginaw to Ludington had been completed in 1874, and a branch from Walhalla to Manistee had been built by the end of 1881.[78] Ashley did express some interest in running into Manistee over the tracks of the Manistee & Northeastern, but nothing ever came of that. In the end, Ashley chose Frankfort. The Frankfort harbor has been described as an "extremely snug harbor, offering excellent protection against storms."[79] The residents of Frankfort were knowledgeable about the value of their harbor. To promote its use, some local businessmen formed their own railroad company, the Frankfort & South Eastern Railroad, on November 9,1885. They proposed to build a narrow gauge line from Frankfort to either the Upper Weldon Bridge in Weldon Township, Benzie County, or to the line of the Grand Rapids & Indiana in Wexford County.[80] This was a strictly local venture and Ashley was not involved in the undertaking.

On November 2,1887, the F&SE's incorporation articles were amended to change the line to a standard gauge one, and on September 22, 1888, to change the eastern terminus to Copemish.[81] Whether these changes were made under Ashley's influence, or were to allow an easier connection with the Manistee & Northeastern which was then building its line from Manistee to Copemish, or were an enticement by the F&SE's owners to Ashley to take over their company, cannot be determined. The most probable reason is the last, since the M&NE connection would have been of only marginal value to the Frankfort promoters. The F&SE completed its line on November 25, 1889, and Ashley's Lake Michigan completed its line on November 17,1889.[82] The meeting point was set at a place named Beecher, located 0.7 miles east of Thompsonville, at MP 270.9.

This construction made the F&SE 22.5 miles in length. The F&SE also built a branch off its line that extended to the docks at Elberta on the south side of Betsie Lake. This branch was about 0.3 miles long and was put in service in 1889.[83] The Lake Michigan, from Cadillac to Beecher, was 42.5 miles long. This is 0.1 mile shorter than the present route; the original line passed about three-quarters of a mile north of Harlan, through a point named Churchill.

The Lake Michigan was transferred to the North Michigan on April 6, 1890.[84] It appears that the Lake Michigan actually did build as far as Copemish, and to allow the Frankfort to comply with its charter obligations, the Lake Michigan leased 2.1 miles between Copemish and Beecher to the F&SE, although the date of the lease is uncertain.[85] Ashley bought the F&SE on May 15, 1892, and added it to the North Michigan.[86] It appears that the F&SE operated as an independent company until the sale, although its owners may have allowed Ashley to operate his trains over it.

In 1889, two more branches were added to the structure of the Ann Arbor. The first was a 1.6 mile spur extended from MP 137.0 into Ithaca.[87] It was on the present right of way used now through Ithaca. At its west end, it may have connected with the Ithaca & Alma line of the Detroit, Lansing & Northern that was built in 1882. The second branch was a 1.1 mile spur in Alma, which extended from the main line, through downtown Alma, to the Pine River.[88] It appears to have been on the present grade south of MP 146.3 and partly along Lincoln Street to its south end at the river. This segment most probably was built in 1885 as part of the LAMP mentioned earlier, but not recorded until 1889 as a separate branch line

In 1890, two more industrial spurs were added. The first was a 1.5 mile branch to the Ross Mill on the Muskegon River.[89] The writer has not been able to locate this branch with certainty. The other was a 1.3 mile spur to the Diggins Mill. [90] This line may have been in the Cadillac area, but has not been located with certainty.

At the end of 1890, the Commissioner of Railroads reports the total mileage of the Toledo, Ann Arbor & North Michigan as 285.56 miles in the state of Michigan. To this figure must be added the 22.75 miles he reports for the Frankfort & South Eastern (F&SE), for a total of 308.31 miles. Table 2 below gives the mileage, as of December 31,1890, as developed in this study:

| Table 2 | |

|

Main Line in Ohio |

|

|

Toledo (Summit St.) - Michigan state line |

5.9 |

|

Main Line in Michigan |

|

|

Ohio state line - Leland |

46.5 |

|

Leland - GTW connection at Hamburg |

8.9 |

|

GTW connection at Lakeland - Durand (old station) |

34.8 |

|

Durand (old station) - Owosso Jct. |

12.2 |

|

Owosso Jct. - St. Louis |

39.0 |

|

Connection near St. Louis - Connection near Alma |

4.2 |

|

Connection near Alma - Mt. Pleasant |

17.5 |

|

Mt. Pleasant - Cadillac |

63.6 |

|

Cadillac - Beecher |

42.5 |

|

Beecher - Frankfort (owned by F&SE) |

22.5 |

|

Total Main Line |

297.6 |

|

Branch Lines in Michigan |

|

|

Leland - South Lyon |

7.6 |

|

to Macon Quarry |

1.6 |

|

to Ithaca |

1.6 |

|

to Pine River in Alma |

1.1 |

| to Ross Mill | 1.5 |

| to Diggins Mill | 1.3 |

| to South Frankfort (owned by F&SE) | 0.3 |

| Total Branch Lines | 15.0 |

|

Total all TAA&NM Michigan lines |

283.9 |

|

Total all F&SE Michigan lines |

22.8 |

|

Total all Michigan lines |

306.7 |

|

(Total, Commissioner of Railroads) |

308.31 |

|

Total all lines |

312.6 |

|

Trackage rights, GTW, Hamburg - Lakeland |

3.9 |

Completing the railroad from Toledo to Frankfort was a monumental achievement. Governor Ashley, with the help of his two sons, had been able to "push a railroad three hundred miles into new undeveloped territory with inadequate money, 'on wind' as Jim Ashley, Junior, put it."[91] It had been built, during the early years at least, without any definite objective, but only as opportunity provided. Ashley got the right of way in the cheapest way he could, and if unsuccessful, would build and settle later with the owners in court. It was built in a very frugal manner, and almost entirely with borrowed money. The earnings of the road paid the interest charges, kept Ashley's credit in good stead, and allowed him to borrow more for more construction. The chief engineer of the Ann Arbor, Henry E. Riggs, commented on the conditions he found on the line when he wrote his recollections of the first inspection trip he made in 1890, when Ashley had hired him and not long after the line had been completed.

My first

trip convinced me that I was on a "jerkwater" railroad.

It was a single-track line, laid with 56-pound rail on ties that

were 90% hemlock with no ballast anywhere on the line except over a

few "sinkholes" where cinder ballast had been used,

probably not over two or three miles in all. The bridges were all of

wood, the great majority small pile or timber trestles.

The equipment at the

beginning of the year was nothing to brag about, but during the year

considerable new passenger equipment was purchased, including

two parlor cars. The Company had, at the end of 1890, thirty-six

locomotives in pretty good condition, but light, and

twenty-four passenger train cars and 1,073 freight train cars, most

of which were old and shabby.[92]

Above: Toledo, Ann Arbor and North Michigan 4-6-0 number 47 is coupled to caboose #25, wearing the road's key herald and the word "caboose" in arched lettering, circa 1894.

Completing the railroad from Toledo to Frankfort was a monumental achievement. Governor Ashley, with the help of his two sons, had been able to "push a railroad three hundred miles into new undeveloped territory with inadequate money, 'on wind' as Jim Ashley, Junior, put it."[91] It had been built, during the early years at least, without any definite objective, but only as opportunity provided. Ashley got the right of way in the cheapest way he could, and if unsuccessful, would build and settle later with the owners in court. It was built in a very frugal manner, and almost

With the rail line completed between Toledo and Lake Michigan Ashley then turned his attention to the cross-lake car ferry service he had envisioned. Package freight and passengers had been carried by lake ships from the very first. In 1888 the Mackinac Transportation Company had begun operating a car ferry service between Mackinaw City and St. Ignace. In 1890 Ashley placed his order for two specially-designed rail car ferries. To hold the market intact for his new service, Ashley began operating the steamer Osceola from Elberta to Kewaunee, Wisconsin in early 1892. Although transloading was needed at both ports, the service was planned to last only until the car ferries were received. The first of the ferries, appropriately, but simply named Ann Arbor No.1, made her first revenue trip from Frankfort on November 24, 1892.[93]

In anticipation of this event Ashley bought the Frankfort & South Eastern on May 15, 1892, and put it into his North Michigan.[94] Ashley paid $75,100 for all of the Frankfort's stock, of which $57,100 went to the owners and $18,000 went to retire outstanding bonds. He also assumed the interest payments on the remaining Frankfort bonds.[95] Probably in the summer of 1892, Ashley extended the Elberta branch to South Frankfort, now named Boat Landing, adding 1.2 miles to the branch.[96]

Traffic on the branch to South Lyon never did develop satisfactorily, and the branch was disposed of. It appears that another company, the South Lyons & Northern, proposed buying the line. That company was formed on May 3, 1890, and proposed to operate a 40 mile road between Leland and Flint.[97] One source states that the sale did take place.[98] It appears, however, that even if a sales agreement was signed, no conveyance of the line ever took place. The 7.6 mile branch from Leland to South Lyon was abandoned on March 29, 1891.[99]

There do not appear to have been any other changes or alterations in the company's route or mileage at this time. The profile of the line between Marion and Park Lake was improved in 1892 and 1893, but this was done without any change in mileage.[l00]

In March of 1893, Ashley's company was not able to pay the interest due on its bonds. Every dollar Ashley had raised or borrowed had been used to build and equip the railroad and to buy the Lake Michigan car ferries. A strike began on March 7, 1893, accompanying the financial Panic of 1893, and the two events brought the company down. Representatives of the bondholders took over the Board of Directors. On April 27, 1893, Wellington R. Burt was appointed by the court as receiver of the company. [101] In March, 1894, Governor James M. Ashley resigned the presidency of the railroad he had created and built. [102]

In the two years and five months that followed Ashley's resignation, under Burt's authority, the company spent substantial sums of money to improve the railroad. Receiver Burt was "one of Michigan's typical lumber barons, wealthy, hard headed, and perfectly willing to spend money for a much better kind of construction and maintenance than that to which the Ann Arbor had ever been accustomed." [103] The road was changed into a "real" railroad line. It is difficult to determine the dates at which all of the various improvement projects were completed, but a summary of them is given, with the caveat that the dates are not completely certain.

Ruling grades in several places were reduced: northward from Milan to Pittsfield, Lakeland to Chilson, and Farwell to Lake George; southward at Homestead Hill, and from Cadillac to Lucas.[104] The line between Durand and Oak Grove was relocated to a completely new route. [105] This relocation was onto a completely new grade between MP 82.7 and MP 95.2, and shortened the line by 1.3 miles. Also rebuilt was the section between Howell and Chilson.[106] The original line was probably only slightly to west of the present line, in the marshy area that still exists. In 1894, the section between Lake George and Temple was rebuilt. A completely new right of way was bought and the Lake George & Muskegon River grade retired for the second time.[107] This alteration subtracted 0.3 miles from the main line; the section that was rebuilt was between MP 192.1 and MP 200.2.

Late in 1893 or early in 1894, the company acquired land for a new passenger terminal in Toledo. The property fronted on Cherry Street, immediately north of the Wheeling & Lake Erie station. A line 2.5 miles in length was built from the new station to a connection with the existing main line. The junction was near Boulevard, just north of Manhattan Boulevard, at MP 2.5, which point was 2.7 miles from the Summit Street station. The former main line was retained and is still owned. Passenger trains began operating into the Cherry Street station in the summer of 1896.[108] With the completion of the new station, the company obtained a new and, for the first time, a permanent general headquarters building.

Also begun in 1894, was a new line north of Ann Arbor. After the abandonment of the South Lyon branch, the remaining main line route made a wide loop through Leland, several miles east of a direct route. The section from Leland to Hamburg also had other problems. Chief engineer Riggs wrote:

This was by all odds the poorest location on this Railroad, if not in the world. The country was flat so that grades were no problem, but the hundreds of degrees of senseless curvature, the seeking of wet swampy worthless land for right of way, the two major sinkholes, and the use of one nine-degree curve with an angle of about 100 degrees, mark it as the work of a schoolboy, not an engineer.[109]

The new section began at MP 47.3, north of Pontiac Trail in Ann Arbor, and extended to the west end of the Grand Trunk Western trackage rights west of Lakeland at MP 62.2, a distance of 14.9 miles. The work was done in two phases. The northern part, from Horseshoe Lake at MP 54.5 to Lakeland was done first. This involved an entirely new line which was completed in 1893.[110] The southernmost three miles, approximately, of this segment was within a few hundred feet and to the west of the present line. At this same time, the trackage rights over the GTW between Lakeland and Hamburg were discontinued. A total of 7.7 miles of line was built in this phase; trackage rights of 3.9 miles were discontinued and 4.2 miles of road abandoned. The southern part, from MP 54.5 to MP 47.3 was completed in the summer of 1896.[111] The line via Leland, 9.6 miles in length, was abandoned and replaced by 7.2 miles of new line through Northfield.

In the fall of 1895, the Ann Arbor filed maps for a new route between Ithaca and Alma, based on surveys made in 1893 and 1894.[112] The route was to run in a rather straight line between MP 137 south of Ithaca and MP 144 south of Wright. This line was never built. Instead, the Ann Arbor began negotiating with the Detroit, Grand Rapids & Western, the successor company to the Detroit, Lansing & Northern. The two companies reached an agreement on February 15, 1897, for an exchange of property. [113] acquire the Alma-Ithaca branch of the DGR&W; the DGR&W would acquire some Ann Arbor tracks in St. Louis; the two companies would build a new line through downtown Alma, much of it along the right of way of the Ann Arbor as originally built by the The Ann Arbor bought tracks extending from MP 138.6 to MP 144.9, and it built a segment from MP 144.9 to about MP 145.6. These two segments added 7.0 miles to the road. At the same time the company abandoned its old line that provided service to St.Louis, comprised of 12.6 miles of main line and the 1.4 mile branch into St. Louis. Some of the trackage in St. Louis was kept and turned over to the DGR&W. This change shortened the ToledoFrankfort line by 3.3 miles. Also, it appears that about this same time the extreme south end of the original LAMP trackage, reaching the Pine River and about 0.4 miles in length, was abandoned. The new construction and the abandonment were completed, probably, before the end of 1897.[114]

Also completed in 1897, was a new route between Boon and Harrietta. It was near the original route, involved no change in mileage, and reduced a 4% grade in that area.[115] A new line was built between MP 261.2 and MP 263.3 that replaced Churchill Hill with a less severe grade; this new line added 0.1 miles of road to the main line. Also built, very probably in 1897, was a new branch to Six Mile Mine, to provide access to a coal mine north of Owosso. The branch began at MP 106.0 and extended north 7.1 miles.[116] During 1897 the 1.5 mile branch to Ross Mill was abandoned.[117] At some time during this period the branch to Macon Quarry may have been abandoned; later maps do show this branch in place after 1900, so this may have been reclassified as an industrial branch.

Table 3 lists the changes made between 1891 and 1900.

| Main Line in Michigan from Table 2 | 291.7 |

| Abandoned: | |

| MP 47.3 - Horseshoe Lake via Leland | -9.6 |

| Horse Lake - GTW connection, Hamburg | -4.2 |

| Built: | |

| MP 47.3 - Horseshoe Lake (MP 54.5) | 7.2 |

| Horseshoe Lake - west of Lakeland (MP 62.2) | 7.7 |

| Relocated: | |

| near Oak Grove (MP 82.7) - Durand (MP 95.2) | -1.3 |

| vicinity of Lake George (MP 192.1 - MP 200.2) | -0.3 |

| Chuchill | 0.1 |

| Abandoned: | |

| line via St. Louis and branch into St. Louis | -14.0 |

| Bought: | |

| Ithaca (MP 138.6) - Wright (MP 146.3) | 6.3 |

| Built: | |

| Wright (MP 144.9) - north of Alma (MP 146.3) | 1.4 |

| Converted from branch line: MP 137.0 - MP 138.6 | 1.6 |

| Conveyed: | |

| Owosso Jct. connection to GTW | -0.1 |

| Total, Main Line in Michigan | 286.5 |

| Main Line in Ohio from Table 2 | 5.9 |

| Built: | |

| Cherry Steet (MP 0) - Boulevard (MP 2.5) | 2.5 |

| Converted to branch line: | |

| Summit Street - Boulevard | -2.7 |

| Total, Main Line in Ohio | 5.7 |

| Total, entire Main Line | 292.2 |

| Branch Lines in Michigan from Table 2 | 15.0 |

| Abandoned: | |

| Leland - South Lyon | -7.6 |

| Pine River Branch in Alma | -1.1 |

| Ross Mill Branch | -1.5 |

| Macon Quarry Branch | -1.6 |

| Built: | |

| Elberta - Boat Landing | 1.2 |

| Six Mile Mine Branch | 7.1 |

| Converted: | |

| Ithaca Branch to Main Line | -1.6 |

| Total, Branch Lines in Michigan | 9.9 |

| Branch Lines in Ohio from Table 2 | |

| Converted from Main Line: | |

| Summit Street - Boulevard | 2.7 |

| Total, Branch Lines in Ohio | 2.7 |

| Total, all Branch Lines | 12.6 |

| Total, all line in Michigan | 296.4 |

| Total, all Lines in Ohio | 8.4 |

| Total, all lines | 304.8 |

Reciver Burt was responsible for the day - to - day operations of the railroad while its financial affairs were being reorganized. Also, he superintended the substantial improvements that were made during the recivership. In the four years two months from April 27, 1893, to July 1, 1897, Burt spent $1,227,183 on roadway and buildings.[118] This sum was about one-fifth the amount that Ashley had spent to build and equip the entire railroad. By the end of the receivership the railroad had been changed intto a much better line than it had been in 1892.

The Lake Michigan car ferry service was as successful as Ashley had envisioned. Reciver Burt expanded the service to additional west shore ports and this, in turn, brought additional freight traffic to the Ann Arbor. The annual increases in traffic pointed out sharply the deficiencies of the physical plant as Ashley had originally built it. Burt's changes in line, some of which Ashley had planned for befoe 1893, improved the plant and allowed it absorv the increased business without difficulty.

To reorganize the property the bondholders conveyed the assets of the North Michigan to the reorganization committee on September 13, 1895.[119] Several of the companies that were transferred to the North Michigan still had bonds outstanding at the beginning of the receivership. The TAA>, the North Michigan (of 1882), the Mt. Pleasant, the Cadillac, and the Lake Michigan, as well as the current North Michigan, had to go through a foreclosure sale on July 2, 1895.[120] These companies' corporate lives finally came to an end. The reorganization committe conveyed the assets to a new company on October 14, 1895.[121]

The Ann Arbor Railroad Company was formed on Sept 20, 1895, and the articles were filed with the state of Michigan the next day.[122] It assumed all the rights and obligations of its predecessor companies. Receiver Burt operated the reorganized company until October 31, 1895.[123] The new corporation began operations on November 1,1895.[124]

The day after it received the assets of the North Michigan the Ann Arbor received the property of the Frankfort & South Eastern. Although Ashley had bought all the rights and property of that company in 1892, it still had bonds outstanding. Therefore, the company passed through the same foreclosure proceedings as the North Michigan's predecessors. The foreclosure sale was held June 4, 1895, and the property transferred to the representatives of the bondholders.[125] They in turned formed a new company, the Escanaba, Frankfort & Southeastern on June 12, 1895, although its incorporation papers were not filed with the Michigan Secretary of State until July 9.[126] On June 12, they transferred the property of the F&SE to the new company. [127] On October 15, 1895, the E&SE deeded its property to the Ann Arbor.[128]

The Kewaunee car ferry service was a reasonably successful one. In 1894, the Ann Arbor began car ferry service to Menominee. In the summer of 1895, service was begun to Gladstone, where a connection was made with the Soo Line. Enroute to Gladstone, ships called at Escanaba for passengers. In the summer of 1896, service was begun to Manitowoc, where a connection was made with the Wisconsin Central. Levels of traffic continued to grow throughout the 1890's. In 1902, the service to Gladstone was replaced with a new direct service to Manistique. [129]

The Menominee ferry service brought an Ann Arbor subsidiary line into being. On June 9, 1899, a wholly-owned company, the Menominee & St. Paul Railway, was formed. It was authorized to build a 10 mile line that would extend from Menominee to the Wisconsin-Michigan state line. [130] In 1900 an 0.6 mile line, extending from the ferry dock, to the tracks of the Chicago & North Western, was put in operation. The Ann Arbor arranged with the C&NW for the latter to provide all the service needed to operate the road.[131]

On June 1, 1905, the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton Railway accumulated a controlling interest in the Ann Arbor. DT&I control continued until April 22, 1910, when the DT&I's receiver offered the stock for sale.[132] On November 25, 1910, the stock was sold to Newman Erb and his associates. Erb set up The Ann Arbor Company on January 5, 1911, as a holding company and he and his partners transferred their stock to it. [133] In April, 1911, the Ann Arbor purchased control of the Manistique & Lake Superior.[134] This acquisition added to the importance of the Frankfort-Manistique car ferry service.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The following works have been used extensively in this study:

Ann Arbor Railroad Technical and Historical Association, Newsletter.

Burgess, G. H. and Kennedy, M. C. Centennial History of the Pennsylvania Railroad (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania RR., 1949).

Ceasar, Ford Stevens. The Lamp Road (Lansing: Wellman, 1983).

Dunbar, Willis F. All Aboard! (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1969).

Hilton, George W. The Great Lakes Car Ferries (Berkeley CA: Howell-North, 1962).

Interstate Commerce Commission, Valuation Docket No. 127, in Val. Docs, vol. 84 (Washington DC, 1924).

Meints, Graydon M. Michigan Railroads and Railroad Companies (East Lansing: Mich. State. Univ., 1992).

Michigan Railroad Commission, Edmund A. Calkins compiler, Aids, Gifts, Grants and Donations to Railroads including Outline of Development and Successions in Titles to Railroads in Michigan (Lansing: Wynkoop, Hallenback, Crawford, 1919).

Riggs, Henry E. The Ann Arbor Railroad 50 Years Ago (Toledo: no publisher, 1947).

|

FOOTNOTES |

||

|

1. Burgess, 228f. 2. Interstate, 192,225; Michigan, 30. 3. Interstate, 193; Michigan, 30. 4. Interstate, 225. 5. Dunbar, 164. 6. Interstate, 192; Meints, 145; Michigan, 30. 7. Dunbar, 164; Michigan, 22. 8. Interstate, 226. 9. Interstate, 226. 10. Interstate, 226; Michigan, 30. 11. Interstate, 226. 12. Riggs, 5. 13. Meints, 143; Michigan, 30. 14. Interstate, 226. 15. Riggs, 18. 16. Interstate, 225. 17. Riggs, 18. 18. Meints, 145; Michigan, 30. 19. Interstate, 223. 20. Michigan, 45. 21. Meints, 145; Michigan, 30. 22. Michigan, 31. 23. Riggs, 19. 24. Michigan, 34ff. 25. Riggs, 19. 26. Meints, 144. 27. Meints, 107; Michigan, 38. 28. Interstate, 222; Michigan, 30, 38. 29. Michigan, 39. 30. Meints, 128; Michigan, 36. 31. Meints, 145; Michigan, 30. 32. Meints, 122, 123; Michigan, 30. 33. Interstate, 221; Michigan, 30. 34. Meints, 145; Michigan, 30. 35. Interstate, 220. 36. Ceasar, 50. 37. Riggs, 19f. 38. Ceasar, 8. 39. Ceasar, 51. 40. Ceasar, 19. 41. Ceasar, 23. 42. Dunbar, 164; Riggs, 6. 43. Riggs, 19. 44. Hilton, 56. |

45. Meints, 145; Michigan, 30. 46. Michigan, 30. 47. Riggs, 23. 48. Riggs, 34, 41. 49. Michigan, 30. 50. Michigan, 31. 51. Riggs, 19. 52. Michigan, 46. 53. Michigan, 46. 54. Meints, 97; Michigan, 30. 55. Ceasar, 81; Interstate, 220. 56. Ceasar, 71. 57. Interstate, 220. 58. Interstate, 220; Meints, 145; Michigan, 31. 59. Ceasar, 80. Michigan, 31, gives June, 1886. 60. Meints, 50, 133, 134; Michigan, 4549. 61. Michigan, 31. 62. Michigan, 30. 63. Michigan, 31. 64. Meints, 145; Michigan, 30. 65. Meints, 143; Michigan, 30. 66. Michigan, 31. 67. Interstate, 212. 68. Riggs, 23, 29, 34. 69. Interstate, 193. 70. Michigan, 30. 71. Interstate, 213. 72. Interstate, 193; Michigan, 32. 73. Michigan, 32. 74. Riggs, 22. 75. Meints, 145; Michigan, 32. 76. Interstate, 211. 77. Riggs, 23. 78. Michigan, 41. 79. Hilton, 69. 80. Meints, 76; Michigan, 32. 81. Interstate, 211; Meints, 76. 82. Interstate, 210-211; Michigan, 33. 83. Michigan, 32. 84. Interstate, 210; Meints, 145; Michigan, 33. 85. Interstate, 211. 86. Interstate, 211; Michigan, 32. 87. Michigan, 32. 88. Michigan, 32. 89. Michigan, 32. |

90. Michigan, 32. 91. Riggs, 1. 92. Riggs, 11-12. 93. Hilton, 69-71. 94. Michigan, 32. 95. Interstate, 211-212. 96. Riggs, 96-97. 97. Meints, 141. The company uses the original name of the village-South Lyons. 98. Interstate, 209. 99. Ann Arbor, Vol. 78-1. 100. Riggs, 29. 101. Interstate, 205; Riggs, 33. 102. Riggs, 31 ff. 103. Riggs, 33. 104. Riggs, 34. 105. Riggs, 23. 106. Riggs, 34. 107. Riggs, 22. 108. Riggs, 20. 109. Riggs, 20-21. 110. Riggs, 20. 111. Riggs, 37. 112. Riggs, 21. 113. Michigan, 33. 114. Michigan, 33. 115. Riggs, 34. 116. Michigan, 32. 117. Michigan, 33. 118. Riggs, 36. 119. Interstate, 205. 120. Michigan, 31, 33. 121. Interstate, 192. 122. Interstate, 172; Meints, 37; Michigan, 32. 123. Interstate, 205. 124. Interstate, 196. 125. Interstate, 205. 126. Interstate, 204; Meints, 73; Michigan, 32. 127. Interstate, 204. 128. Interstate, 204; Michigan, 33. 129. Hilton, 69ff. 130. Meints, 106; Michigan, 32. 131. Interstate, 179-180. 132. Interstate, 191-192. 133. Interstate, 192. 134. Dunbar, 169. |

APPENDIX 1

The correct legal names of the companies which made up the Ann Arbor, as given in the corporate articles of organization, articles of association, or articles of consolidation, as filed with the Secretary of State of Michigan, on file with the Corporation and Securities Division, Lansing, are as follows. The data given is: 1. full legal name, 2. date of articles and date filed with Secretary of State, and initial capitalization, 3. stated purpose of company, 4. effective date and disposition of company.

APPENDIX 2.

In addition to the construction of the Toledo-Frankfort railroad line, Governor Ashley also was involved to some extent in the construction of two other railroad lines. In 1884 he had completed his own line between Owosso and St. Louis and in ] 885 had connected it to the southern part of his line.

On January 20, 1886, and filed January 25, the Toledo, Saginaw & Muskegon Railway was formed to build a 140 mile line from Muskegon eastward. On February 13,1886, the company amended its incorporation papers so it could build a 156 mile line and established Bay City as the eastern terminus. James M. Ashley, Ammi W. Wright, William Baker, David Robison, Jr., John Cummings, Edward Middleton, and Lyman G. Mason were the first directors of this road. The extent of Ashley's financial involvement is not known now; it is probable that he supported the project more with technical than financial assistance.

The contract to build the road was signed on October 2, 1886, but Ashley was not the construction contractor. That part of the Muskegon's line between Carson City and Ashley, where the line connected with Ashley's own railroad, was put in service on September 24, 1887. But the prospects of the company seem to have been rather bleak. On May 10, 1888, the Muskegon's owners signed a traffic-sharing agreement with the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada, which was not enthusiastic about another line paralleling its Owosso-Grand Haven route and competing for traffic. On August 1, 1888, when the line was completed into Muskegon, the Grand Trunk bought up all the Muskegon's capital stock and made it their own. As part of the deal Ashley gave the Grand Trunk trackage rights over the Ann Arbor line between Ashley and Owosso Junction-to link the disconnected segment to the rest of the Grand Trunk's system.

Shortly after the Muskegon line was conceived Ashley and Wright developed another project: the Toledo, Saginaw & Mackinaw Railroad. It was formed on June 28, 1887, and was to build a 250 mile road from Durand, via Saginaw, to Mackinaw City. In with Ashley and Wright were Wellington R. Burt, Phillip H. Ketcham, Charles W. Wells, William C. McClure and Thomas Merrill. On October 23,1888, the first section of line, between Durand and Flushing, was put into service. On December 17, 1888, through passenger train service was begun into Saginaw. The owners had agreed to have Ashley operate their railroad for them. The Commissioner of Railroads Annual Report for 1888 and 1889 show the Mackinaw's mileage as operated by the Ann Arbor.

Just why is not clear, but on January 1, 1890, the line was sold to a new company, the Cincinnati, Saginaw & Mackinaw Rail Road, formed on December 26, 1889. Burt and Wright are among the first directors of the new Mackinaw, but Ashley was out. The new owners offered the line to the Grand Trunk which, on November 1, 1890, began operating the company. In 1901 the Grand Trunk leased the company for 99 years, and in 1943 bought the company outright.

Web page by Henry F. Burger 1/5/2014