Myself, Bob and Elizabeth met in the lobby of the Baymont Inn and went to Bob Evans for breakfast then Elizabeth drove us to Dearborn and I gave her directions to get to the Henry Ford Museum.

Henry Ford Museum HistoryAlthough Henry Ford became one of the world's wealthiest and most powerful industrialists, he never forgot the values of the rural life he had left behind growing up on a farm. His interest in collecting began in 1914, as he searched for McGuffey Readers to verify a long-remembered verse from one of his old grade school recitations. Soon, the clocks and watches he had loved tinkering with and repairing since childhood grew into a collection of their own. Before long, he was accumulating the objects of ordinary people, items connected with his heroes and from his own past, and examples of industrial progress.

In 1919, Henry Ford learned that his birthplace was at risk because of a road improvement project. He took charge, moving the farmhouse and restoring it to the way he remembered it from the time of his mother's death in 1876, when he was 13. He and his assistants combed the countryside for items that he remembered and insisted on tracking down. He followed this up by restoring his old one-room school, Scotch Settlement School; the 1686 Wayside Inn in South Sudbury, Massachusetts (with a plan to develop a "working" colonial village); and the 1836 Botsford Inn in Farmington, Michigan, a stagecoach inn where he and his wife Clara had once attended old-fashioned dances. These restorations gave Ford many opportunities to add to his rapidly growing collections while honing his ideas for his own historic village.

In the early 1920's, Henry Ford moved his growing hoard of antiques into a vacated tractor assembly building. The objects fit every description. Large items hung from rafters; smaller ones sat on makeshift benches and racks. Watches and clocks hung along the wall. Henry and his wife Clara enjoyed sharing their relics with others. Once people learned Ford was collecting objects for a museum, they flooded his office with letters offering to give or sell him antiques. Ford also sent out assistants to help him find and acquire the kinds of objects he felt were important to preserve. Goods intended for the museum arrived in Dearborn almost daily -- sometimes by the train-car full. By the late 1920's, Henry Ford had become the primary collector of Americana in the world.

Greenfield VillageFord's historic village was to be organized around a village green, to include a courthouse, town hall, church, general store, tavern and school. Homes were installed along a road beyond the green. Industrial buildings, such as a carding mill, sawmill and gristmill were made operational. A centerpiece of the Village was the re-creation of the Menlo Park, New Jersey laboratory complex where Thomas Edison had invented his electric lighting system. Henry Ford engaged Ford Motor Company draftsman Edward J. Cutler to draw up plans. The first buildings began arriving in 1928. Labourers dug foundations, reconstructed buildings, cleared trees, laid out roads and hauled supplies through muddy fields. Some buildings were designed right in the Village, at Ford's request.

While Cutler labored in the muddy fields of Greenfield Village, architect Robert O. Derrick was designing a large indoor museum adjacent to the historical village to house the objects Ford had collected. Derrick suggested that the facade should resemble Independence Hall and related buildings of Philadelphia, with a large "Exhibition Hall" in back. Since Henry Ford had rejected the notion of storage rooms, nearly everything had to be exhibited out in the open. The twelve-acre museum contained a glorious assemblage of stuff. To Ford, that assemblage represented the evolution of technological progress.

For nearly a decade after the museum officially opened to the public in 1933, visitors found it a work in progress. The exhibits would not be completed until the early 1940s. Henry Ford decided on October 21st, 1929 as the dedication date for his new museum and village -- marking the fiftieth anniversary of Thomas Edison's first successful experiment with a suitable approach to manufacturing an incandescent lamp. The night of the "Light's Golden Jubilee" celebration, crowds cheered as President Hoover, Edison and Ford ceremoniously arrived in a train pulled by an 1850's locomotive. After an elegant dinner in the museum, the three men went out to the restored Menlo Park Laboratory in Greenfield Village. There, the 82-year-old Edison re-created the lighting of his incandescent lamp. The event was broadcast live over national radio. Henry Ford named his new complex The Edison Institute of Technology, to honor his friend and lifelong hero Thomas Edison.

Henry Ford didn't consider Greenfield Village finished upon opening. He continued to select homes, mills and shops that he felt best reflected the way Americans had lived and worked, or that were associated with famous people he admired. Individuals even began to offer Ford historic structures for his Village. By the mid-1930s, several Village shops were staffed by people demonstrating traditional craft skills, including glassblowers, blacksmiths, weavers, shoemakers and potters. Visitors to Greenfield Village not only had the pleasure of watching the craftsmen work, they could also buy samples of their hand-crafted products. Craftsmen like brick makers and sawyers supported the Village restoration efforts. By the early 1940's, Greenfield Village had grown to over 70 buildings.

Early on, Henry Ford's vision for his Museum and Village was to provide hands-on learning opportunities for students. His philosophy of education was "learn to do by doing". He believed that "by looking at the things that people used and how they lived, a better and truer impression can be gained than could be had in a month of reading." It was a way of learning that Ford had experienced during his own childhood, and the way, in fact, that he himself learned best. In Henry Ford’s Edison Institute schools, students would learn not only from books, but also from objects and hands-on experiences.

Henry Ford's SchoolIn September 1929, Henry Ford's Edison Institute school system began at Scotch Settlement School in Greenfield Village, with 32 grade school children. Students were taught using both traditional and progressive methods. Standard academic subjects like reading, arithmetic, geography and science were at the core of their studies. Pupils also used the artifacts and many of the historic buildings in the village for practical learning. Girls learned housekeeping skills while boys got experience operating machinery. Only when visitors pressed for regular access was the Village formally opened to the public. Ford made it clear that, despite the presence of paying guests, there was no place off-limits to the schoolchildren. As the original students grew older, grades and buildings were added to accommodate them and other students who attended the school. A high school with classrooms in the Museum was added in 1934, with the first graduating class in 1937. The Edison Institute of Technology -- a work-study engineering college -- was added in 1937, with classes and labs in the Recreation Building (later called Lovett Hall). Many historic buildings in Greenfield Village accommodated full-time student activities. It was "education through experience" everywhere. At its peak in 1940, 300 students were enrolled in the Edison Institute Schools. This school system also came to include rural schools in other parts of Michigan and other regions of the United States as well as in England and Brazil.

We parked in the parking lot and walked into Greenfield Village.

The flower display as you enter the grounds.

We waited by the fountain, part of the Josephine E. Ford Plaza, for Carrie Nolan, Manager of Media and Film Relations, to arrive which she did shortly and took us to the Roundhouse.

We walked by this water wheel, which have always amazed me.

The Roundhouse Sign.

The replica Detroit, Toledo and Milwaukee roundhouse at Greenfield Village, built in 2000. We were taken inside and met Matthew Goodman, steam mechanic and hostler, who would give us a tour.

Edison Institute 4-4-0 7, ex. Henry Ford 7 1921, exx. Detroit, Toledo and Ironton Railroad 7, exxx. Detroit, Toledo and Ironton Railway 7, exxxx. Detroit Southern Railroad Company 7, nee Detroit and Lima Northern 7 built by Baldwin in 1897. It was Henry Ford's personal locomotive when he owned the DT&I.

Greenfield Village 4-4-0 1 "Edison", based on an 0-4-0 switcher locomotive built about 1870 by Manchester Locomotive Company. Henry Ford purchased the switcher from Edison Portland Cement Company in 1932 and had it rebuilt into a 4-4-0 wheel arrangement by staff at Ford Motor Company's Rouge locomotive shop.

Plymouth JLC 14 ton gasoline switcher, nee Detroit Public Light built in 1927 is used for switching cars and cold locomotives.

The Plymouth's engine.

Here is Matthew Goodman who was on the train with us to Cadillac yesterday.

This 1947 speeder just restored three months ago is used for track inspection after storms.

Detroit and Mackinac caboose W52 built in 1912 under restoration.

Hand car. We were then taken up to the mezzanine level.

Edison Institute 4-4-2 8085, ex. Detroit, Toledo and Ironton 45 1926, exx. Michigan Central Railraod 8085 1915, exxx. Michigan Central Railroad 7953 1905, nee Michigan Central Railroad 254 built by American Locomotive Company in 1902 for fast passenger steamer between Detroit and Chicago. Henry Ford bought this Atlantic type from the Michigan Central for $50,000. Later it was refitted with gold brass and wood trim at the Ford Motor Company's Rouge Locomotive Shop in Dearborn.

This locomotive has been relocated from the Henry Ford Museum to the DT&M Roundhouse as part of the guided tour, so that visitors could look go into the work pit to see underside of an locomotive.

Edison Institute 4-4-0 7.

The inspection pit where every night the running locomotive undegoes a one-and-a-half hour inspection.

Looking down on Greenfield Village 4-4-0 1 "Edison".

Views from the mezzanine.

Facts about American Roundhouses.

How a steam engine works.

400 ton wheel press.

Welcome to the Roundhouse.

The Board for running the railroad.

Bridgeford axle lathe. From here we went outside.

One of the open passenger cars used on the Weiser Railroad.

Ash hoist.

Naval Ammunition Depot 45 ton switcher 1 from Charleston, South Carolina, nee United States Navy 65-00002 built by General Electric in 1942. It was acquired in 1993 from Luria Brothers Scrapyard in Ecorse, Michigan and is used as a switcher and backup power for the steam locomotives.

Detroit River Tunnel Company 120 ton crane 1, which was never used in that operation.

The crane's builder's plate.

Detroit and Mackinac 0-6-0 8, ex. C.A. Pinkerton {Detroit and Mackinac} 8, exx. A. Fivenson Iron and Metal Co, exxx. Huron Portland Cement 6, nee Michigan Alkali 8 built by Baldwin in 1908. The Detroit and Mackinac rebuilt the locomotive during the 1970's and it ran on a limited basis for their railroad employees until the steam locomotive, three passenger cars, and a caboose were donated to the museum in 1979.

The tender of the steam engine.

The builder's plate.

The Greenfield Village water tank whose capacity is 3,900 gallons.

Looking back towards the roundhouse.

Chesapeake and Ohio box car 19464 built by American Car and Foundry in 1957.

Chesapeake and Ohio box car 491556 built by the railroad, year unknown.

Chesapeake and Ohio box car 19385 built by American Car and Foundry in 1957.

Chesapeake and Ohio box car 19462 built by American Car and Foundry in 1957.

Canadian Pacific Railway stock car 277111 built by Canadian Car and Foundry in 1958 and rebuilt in the 1960's.

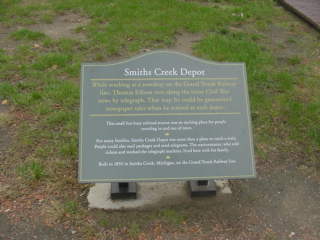

The Grand Trunk Railway Smiths Creek depot built in 1859. It was now time to return to the boarding area to ride the train on the Weiser Railroad. We thanked both Matthew and Carrie for our visit.